Remarks on Kaempferʼs Imatto Canna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Hyakunin Isshu Translated Into Danish

The Hyakunin Isshu translated into Danish Inherent difficulties in translation and differences from English & Swedish versions By Anna G Bouchikas [email protected] Bachelor Thesis Lund University Japanese Centre for Languages and Literature, Japanese Studies Spring Term 2017 Supervisor: Shinichiro Ishihara ABSTRACT In this thesis, translation of classic Japanese poetry into Danish will be examined in the form of analysing translations of the Ogura Hyakunin Isshu. Difficulties will be surveyed, and ways of handling them will be suggested. Furthermore, differences between the Danish translations and those of English and Swedish translations will be noted. Relevant translation methods will be presented, as well as an introduction to translation, to further the understanding of the reader in the discussion. The hypothesis for this study was that when translating the Hyakunin Isshu into Danish, the translator would be forced to make certain compromises. The results supported this hypothesis. When translating from Japanese to Danish, the translator faces difficulties such as following the metre, including double meaning, cultural differences and special features of Japanese poetry. To adequately deal with these difficulties, the translator must be willing to compromise in the final translation. Which compromises the translator must make depends on the purpose of the translation. Keywords: translation; classical Japanese; poetry; Ogura Hyakunin Isshu; Japanese; Danish; English; Swedish ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First of all, I would like to thank both of my informants for being willing to spend as much time helping me as they have. Had they not taken the time they did to answer all of my never- ending questions, surely I would still be doing my study even now. -

Haiku in Romania by Vasile Moldovan

Haiku in Romania by Vasile Moldovan Romanian poets expressed their interest in Japanese culture as early as at the very beginning of the 20th century. Two classics of Romanian literature, Alexandru Macedonski and Vasile Alecsandri, were fascinated by the beauty of Japanese landscape poems, and wrote several poems inspired by classical Japanese literature. First Romanian essays on haiku and tanka appeared in the Iasi-based Literary Event magazine in 1904. In the same year, the poet Al Vlahuta published an essay titled “The Japanese Poetry and Painting” in the By the Fireside magazine; this essay contained a number of tanka and haiku poems. Poet Al. T. Stamatiad published the first haiku poems in Romanian language, 12 in total, in the anthology titled Tender Landscape, which won the Romanian Academy Prize. In the 1930s, the poet Ion Pillat experimented with one-line poems, many of which resembled haiku. His best miniatures appeared in his collection that he called- One-line Poems (1935). These poems usually had a caesura and comprised of thirteen to fourteen syllables. In the preface he claimed that even if his poems differ from mainstream haiku they should be regarded as a form of haikai poetry. Pillat’s book proved to be influential, and nowadays many Romanian poets follow this trend. At approximately the same time poet Traian Chelariu published Nippon soul, an anthology of classical Japanese poetry in his translations (incidentally, he translated it through German). Chelariu adhered to the 5-7-5 pattern, which afterwards influenced many Romanian authors of haiku. In 1942, Al. T. Stamatiad published Nippon Courtesan Songs. -

Kaempfer's Album of Famous Sights of Seventeenth Century Japan

KAEMPFER'S ALBUM OF FAMOUS SIGHTS OF SEVENTEENTH CENTURY JAPAN YU-YING BROWN WITHIN the covers of a large and weighty album bound in western style and preserved in The (Western) Manuscript Collections of the British Library (Add. MS. 5252; bearing Sloane's old classification 'Bibliothecae Sloanianae Min. 47') are to be found three groups of curiously varied material. The first consists of a series of fifty Japanese paintings executed in brilhant colours and in gold, each on paper measuring 215 x 322 mm. (ff. 1-50). They depict famous sights of Japan enlivened by vignettes of people engaged in a variety of activities, though mostly pleasure outings or pilgrimages to shrines, temples and scenic spots. The second comprises seven Japanese figure drawings mounted on ff. 53-59, together with three padded applique pictures (ff. 68-70), now identified as oshie (pressed pictures). The third group seems to be entirely Chinese in origin. It consists of twenty-six floral and figure pictures in silk brocade or embroidery (ff. 51, 52, 60-67, i00"i5)- These otherwise unrelated groups of items have one thing in common. They were all smuggled out of Japan in 1692 by the German physician and traveller, Dr Engelbert Kaempfer (1651-1716), and have all, until recently, lain dormant, in pristine condition, among the British Museum's foundation collections.^ This paper seeks to introduce the first and major part of the album only, namely the remarkable set of fifty miniature paintings. These are of unique importance for all historians of Japanese art and culture as well as for specialists in 'Kaempfer studies'. -

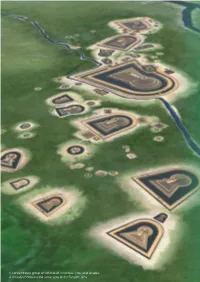

A Concentrated Group of Kofun Built in Various Sizes and Shapes a Virtually Reconstructed Aerial View of the Furuichi Area Chapter 3

A concentrated group of kofun built in various sizes and shapes A virtually reconstructed aerial view of the Furuichi area Chapter 3 Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.1.b Criteria under Which Inscription is Proposed 3.1.c Statement of Integrity 3.1.d Statement of Authenticity 3.1.e Protection and Management Requirements 3.2 Comparative Analysis 3.3 Proposed Statement of Outstanding Universal Value 3.1.a Brief Synthesis 3.Justification for Inscription 3.1.a Brief Synthesis The property “Mozu-Furuichi Kofun Group” is a tomb group of the king’s clan and the clan’s affiliates that ruled the ancient Japanese archipelago and took charge of diplomacy with contemporary East Asian powers. The tombs were constructed between the late 4th century and the late 5th century, which was the peak of the Kofun period, characterized by construction of distinctive mounded tombs called kofun. A set of 49 kofun in 45 component parts is located on a plateau overlooking the bay which was the maritime gateway to the continent, in the southern part of the Osaka Plain which was one of the important political cultural centers. The property includes many tombs with plans in the shape of a keyhole, a feature unique in the world, on an extraordinary scale of civil engineering work in terms of world-wide constructions; among these tombs several measure as much as 500 meters in mound length. They form a group, along with smaller tombs that are differentiated by their various sizes and shapes. In contrast to the type of burial mound commonly found in many parts of the world, which is an earth or piled- stone mound forming a simple covering over a coffin or a burial chamber, kofun are architectural achievements with geometrically elaborate designs created as a stage for funerary rituals, decorated with haniwa clay figures. -

Basic Study on Oharidadera and Taikoji Temples

Bulletin of the National Museum of Japanese History Vol. 179 November 2013 Basic Study on Oharidadera and Taikoji Temples YOSHIKAWA Shinji The abandoned temple of Okuyama (Okuyama Kumedera Temple) located at Okuyama in Asuka Village, Nara Prefecture is considered to be an old temple founded in the 620s or 630s, and identified with the Oharidadera Temple found in bibliographical sources of olden times. However, with regard to the circumstances of the foundation of the Oharidadera Temple, to date, no firmly established theory has been formed. In this paper by rereading historical materials relating to ancient times through to the medieval period, the following conclusions were obtained. 1. Oharidadera Temple in Asuka was the leading convent in the late 7th century, and even in the 8th century the temple had a close relation with the Imperial Family. It was confirmed that concurrently with the relocation of the capital to Heijyo-kyo, the temple was moved to the northern outskirts of Heijyo-kyo, and the new temple was also called Oharidadera. 2. The Taikoji Temple in Nara, mentioned in historical materials covering the Heian period and later, in view of its geographical position, can be assumed to be the same as the Heijyo Oharidadera Temple. It would be reasonable to consider that Oharidadera Temple had the Buddhist name, Taikoji, since before the relocation of the capital to Heijyo-kyo. 3. Private estates owned by Taikoji Temple in Yamato Province, mentioned in the Kanyo Ruijusho collection, were systematically arranged in locations convenient for overland transportation on the Nakatsu-Michi road and water transport on the Yamato River; against this background a strong admin- istrative and financial power can be inferred. -

Glimpses of Medicine in Early Japanese-German Intercourse

九州大学学術情報リポジトリ Kyushu University Institutional Repository Glimpses of medicine in early Japanese-German intercourse Michel, Wolfgang (Michel-Zaitsu) Kyushu University : Professor emeritus http://hdl.handle.net/2324/20441 出版情報:pp.72-94, 2011-12-26. 財団法人 日本国際医学協会 バージョン: 権利関係: Chapter 1 Glimpses of medicine in early Japanese-German intercourse Wolfgang Michel, MA, PhD Permanent Exective Board Member, Japan Society for Medical History, Professor emeritus, Kyushu University For most of the Edo period, encounters between Japanese and Germans took place within the framework of Dutch-Japanese intercourse. World maps and occasional writings such as the “Notes on Western Countries” (Seiyō kibun, 1715) by Arai Hakuseki referred to the existence of Germany (Zerumania), but this was of little significance in actual encounters, as every European setting foot on Japanese soil officially had to be a ‘Redhead’ (kōmōjin) from Holland (Oranda). Nevertheless, a considerable number of merchants, physicians, surgeons, and pharmacists at the trading post at Dejima in Nagasaki came from German-speaking regions. Some of them made significant contributions to mutual understanding between Japan and Europe. Various German books in Dutch translation also provided Japanese 72 scholars with new perspectives on man and nature. This essay discusses the early stage of German-Japanese encounters and the gradual absorption of Western medicine and allied disciplines into Japan. Growing awareness of weaknesses and needs During the 15th and 16th centuries, Japan absorbed a number of foreign innovations in smelting and forging methods and in crafts such as papermaking, silk weaving, and printing. Most of this know-how came from China. It was disseminated not by Buddhist monks or scholars as earlier knowledge had been, but by merchants and artisans; hence it was predominantly of a practical nature. -

Island Narratives in the Making of Japan: the Kojiki in Geocultural Context

Island Studies Journal, Ahead of print Island narratives in the making of Japan: The Kojiki in geocultural context Henry Johnson University of Otago [email protected] Abstract: Shintō, the national religion of Japan, is grounded in the mythological narratives that are found in the 8th-Century chronicle, Kojiki 古事記 (712). Within this early source book of Japanese history, myth, and national origins, there are many accounts of islands (terrestrial and imaginary), which provide a foundation for comprehending the geographical cosmology (i.e., sacred space) of Japan’s territorial boundaries and the nearby region in the 8th Century, as well as the ritualistic significance of some of the country’s islands to this day. Within a complex geocultural genealogy of gods that links geography to mythology and the Japanese imperial line, land and life were created along with a number of small and large islands. Drawing on theoretical work and case studies that explore the geopolitics of border islands, this article offers a critical study of this ancient work of Japanese history with specific reference to islands and their significance in mapping Japan. Arguing that a characteristic of islandness in Japan has an inherent connection with Shintō religious myth, the article shows how mythological islanding permeates geographic, social, and cultural terrains. The discussion maps the island narratives found in the Kojiki within a framework that identifies and discusses toponymy, geography, and meaning in this island nation’s mythology. Keywords: ancient Japan, border islands, geopolitics, Kojiki, mapping, mythology https://doi.org/10.24043/isj.164 • Received July 2020, accepted April 2021 © Island Studies Journal, 2021 Introduction This study interprets the significance of islands in Japanese mythological history. -

Tsugiki, a Grafting: the Life and Poetry of a Japanese Pioneer Woman in Washington Columbia Magazine, Spring 2005: Vol

Tsugiki, a Grafting: The Life and Poetry of a Japanese Pioneer Woman in Washington Columbia Magazine, Spring 2005: Vol. 19, No. 1 By Gail M. Nomura In the imagination of most of us, the pioneer woman is represented by a sunbonneted Caucasian traveling westward on the American Plains. Few are aware of the pioneer women who crossed the Pacific Ocean east to America from Japan. Among these Japanese pioneer women were some whose destiny lay in the Pacific Northwest. In Washington, pioneer women from Japan, the Issei or first (immigrant) generation, and their Nisei, second-generation, American-born daughters, made up the largest group of nonwhite ethnic women in the state for most of the first half of the 20th century. These women contributed their labor in agriculture and small businesses to help develop the state’s economy. Moreover, they were essential to the establishment of a viable Japanese American community in Washington. Yet, little is known of the history of these women. What follows is the story of one Japanese pioneer woman, Teiko Tomita. An examination of her life offers insight into the historical experience of other Japanese pioneer women in Washington. Beyond an oral history obtained through interviews, Tomita’s experience is illumined by the rich legacy of tanka poems she wrote since she was a high school girl in Japan. The tanka written by Tomita served as a form of journal for her, a way of expressing her innermost thoughts as she became part of America. Indeed, Tsugiki, the title Tomita gave her section of a poetry anthology, meaning a grafting or a grafted tree, reflects her vision of a Japanese American grafted community rooting itself in Washington through the pioneering experiences of women like herself. -

Book Reviews

Book Reviews Trew made himself known as an able extensively and at the same level with the medical practitioner, teacher of anatomy and physician Loelius at the Ansbach court. As a botany, collector in natural history, editor of non-resident personal physician to the same one of the first medical periodicals-the court, Trew was frequently consulted by his Commercium litterarium-and of colleague. In the patronage relationship magnificently illustrated botanical works (see between (noble) patient and doctor, Trew's also my notice of T Schnalke [ed.], Natur im geographical distance from the court rather Bild in Med. Hist. 1996, 40: 529). His enhanced his medical authority. Patients' surviving correspondence, a total of 4,831 estimation of his medical advice "from a letters to him and 873 from him, was linked to distance" is likewise reflected in his a large extent to these activities. Schnalke has consultations with the younger Physicus selected for his study five representative Gruner in Grafenberg near Nuremberg. Perhaps correspondences, in which Trew entertained the most remarkable of the five dialogues with a medical professor (Albrecht correspondences studied by Schnalke is that von Haller), a court surgeon (Carl Friedrich with May, an apprenticeship-trained surgeon, Gladbach), a court physician (Johann Lorenz who had been taught anatomy by Trew in Ludwig Loelius), a Physicus, i.e. medical Nuremberg and then went to Strasbourg, where officer (Christian Albrecht Gotthold Gruner), he made an academic career as a surgical and an academic surgeon (Johann Cristoph teacher, prosector, and demonstrator of May). anatomy. In various ways May was aided in his A number of issues that are characteristic of career by Trew as well as by the Strasbourg Enlightenment medicine feature in these professors of anatomy and surgery Johann letters, e.g. -

Origins and Characteristics of the Japanese Collection in the British Library

ORIGINS AND CHARACTERISTICS OF THE JAPANESE COLLECTION IN THE BRITISH LIBRARY YU-YING BROWN THE British Library's antiquarian Japanese collection has long been regarded as one of the finest outside Japan.^ Its quality and quantity are such that the descriptive catalogue^ compiled by my predecessor, the late Kenneth Gardner,^ had to be limited to pre-1700 printed books. Even then, it included 637 items of outstanding rarity.^ These range from the Hyakumanto daratii ^-^m^tmf^ (Empress Shotoku's 'One Million Pagoda Charms') of AD 764-70; to books printed in medieval Buddhist monasteries (imprints known as Kastiga-ban ^B^^ Jodokyo-ban &±^f&yKdya-ban ,^if-lfe, etc., from the names of their associated temples or sects); Chinese classical works printed in Japan (especially Gozan- ban ELUtife ); and the early movable-type editions (Kokatsuji-ban ^ffi^^tK), which include Saga-bon ^m'^ and those rarest of all Japanese books, volumes printed by the Jesuit Mission Press, the Kirishitan-ban ^ u •>? >W.. In the category of Kokatsuji-ban., the best yardstick with which to measure the comparative strength of fine antiquarian collections, the British Library has about 120, a holding comparable with those of such great Japanese libraries as Tenri Central Library in Nara, Daitokyu Memorial Library and the Toyo Bunko (Oriental Library) in Tokyo. The early date and rarity of much of the Japanese collection in the British Library owes a good deal to the acquisitions made by the British Museum, through purchase and gift, from four inspired collectors. They were Engelbert Kaempfer (1651-1716),^ a German physician and traveller who worked at Deshima, the Dutch East India Company's trading post in Nagasaki; Phihpp Franz von Siebold (1796-1866), Kaempfer's compatriot and likewise a doctor at Deshima; Sir Ernest Satow (1843-1929), a distinguished British diplomat and bibliophile; and William Anderson (1842-1900), a Scottish surgeon. -

Engelbert Kaempfer's Intercultural Contacts Shamakhi 1683-1684

Discovering Azerbaijan Lothar WEYS Doctor of History Kamil IBRAHIMOV Doctor of History Engelbert Kaempfer’s intercultural contacts Shamakhi 1683-1684 s secretary of a Swedish delegation to the court of Shah Suleyman, Engelbert Kaempfer (1651- A1716) travelled through what is today Azerbaijan for 77 days. He stayed in Shamakhi, the former capital of the Persian province of Shirvan, for four weeks, includ- ing his visit to Baku and the oil fields of Absheron. Not so well known are details of his stay in Shamakhi. His diary and book with five entries from Shamakhi in five lan- guages give the names of seven of his local or foreign contacts - clerics of different nominations, military men and diplomats from different nations. Identifications of his contacts and details of their lives can be found in Kaempfer’s “Amoenitates” and books by European and Persian travelers, Chardin, Tavernier and Ibn Muham- mad Ibrahim. All this shows Shamakhi as an important place of intercultural contacts. For 10 years from 1683 to 1692, German physician Engelbert Kaempfer (1651-1716) travelled through parts of Russia, Persia, India, Siam, Japan and South Af- rica. First as secretary of a Swedish delegation he came to the court of the Persian Shah Suleyman. Later in the Engelbert Kaempfer 4 www.irs-az.com 4(41), AUTUMN 2019 Cover of E. Kaempfer’s book on natural and political characteristics of the countries he visited. 1712 service of the Dutch trading company “Verenigde Oost- Kaempfer in Shamakhi. Unlike his report on Baku, indische Compagnie” he traveled to Japan. His “History he doesn’t give a printed report of his stay in this town of Japan” published in London in 1727 was a reference in December 1683-January 1684. -

The Basic Structure of Tanka Prose

The Elements of Tanka Prose by Jeffrey Woodward Introduction: Basic Definition The marriage of prose and waka, the forerunner of modern tanka, occurred early in the history of Japanese literature, from the 8th to 11th centuries, with rudimentary beginnings in the Man’yōshū and later elaboration as an art in the Tales of Ise and Tale of Genji. One aspect of the proliferation of prose with waka forms is that practice moved far in advance of theory. Japanese criticism to this day lacks consensus on a name for this hybrid genre. The student, instead, is met with a plethora of terms that aspire to be form-specific, e.g., preface or headnote (kotobagaki), poem tale (uta monogatari), literary diary (nikki bungaku), travel account (kikō), poetic collection (kashū), private poetry collection (shikashū) and many more [Konishi, II, 256-258; Miner, 14-16] The first problem one must address, therefore, in any discussion of tanka plus prose is terminology. While Japanese waka practice and criticism afford no precedent, the analogy of tanka with prose to the latter development of haibun does. The term haibun, when applied to a species of literary composition, commonly signifies haiku plus prose written in the ―haikai spirit.‖ It would not be mere license to replace haibun with haiku prose or haikai prose as proper nomenclature. Upon the same grounds, tanka prose becomes a reasonable term to apply to literary specimens that incorporate tanka plus prose – a circumstance which may lead one to inquire, not unreasonably, whether tanka prose also indicates prose composed in the ―tanka spirit.‖ Fundamental Structure of Tanka Prose Tanka prose, like haibun, combines the two modes of writing: verse and prose.