Under Ground: Archaeological Clues to Tucson’S Past

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Presidio Trail a Historical Walking Tour of Downtown Tucson

This historical walk, designed A Historical Walking Tour as a loop, begins and ends at of Downtown Tucson the intersection of Church and The Presidio Trail Washington Streets, the north- east corner of Tucson’s historic presidio. The complete walk (about 21/2 miles in length) takes 1 1/2 to 2 hours, but it can, of course, be done in segments, beginning and ending wherever you like. More than 20 restaurants are within a few blocks of the walk, C providing plenty of opportunities for lunch or a break. Most of the B sites on the tour are marked with historical plaques that provide additional information. Santa Cruz River Enjoy this walk through the heart of our city, which has expanded Just follow the turquoise striped path to out from the adobe fort that was visit each NUMBERED site. Sites its beginning. designated with LETTERS are not directly on the tour, but are interesting locations that can be viewed from the tour P route or are close by. 1 Presidio San Agustín de Tucson 2 Pima County Courthouse 9 3 Mormon Battalion Sculpture D 4 Soldado de Cuera (Leather 10 8 22 Jacket Soldier) Sculpture 12 11 W 4 5 Allande Footbridge 6 5 3 23 6 Garcés Footbridge 13 7 7 Gazebo in Plaza de Mesilla rsCenter 1 14 Visito 2 (La Placita) A A Francisco “Pancho” Villa Statue R P 8 Sosa-Carrillo-Frémont House W P 15 E 21 9 Jácome Art Panel at Tucson P H I Convention Center B Sentinel Peak/“A” Mountain G C Tumamoc (Horned Lizard) Hill 16 10 El Tiradito (The Castaway), also known as The Wishing Shrine F P 11 La Pilita D Carrillo Gardens/Elysian Grove & Market 17 18 12 Carrillo Elementary School R 13 Teatro Carmen W 20 14 Ferrin House (now Cushing Street R Bar & Restaurant) 19 W 15 Barrio Viejo Streetscape 20 Historic Railroad Depot Map by Wolf Forrest 16 Temple of Music & Art H Pioneer Hotel Building E St. -

Feasibility Study for the SANTA CRUZ VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA

Feasibility Study for the SANTA CRUZ VALLEY NATIONAL HERITAGE AREA FINAL Prepared by the Center for Desert Archaeology April 2005 CREDITS Assembled and edited by: Jonathan Mabry, Center for Desert Archaeology Contributions by (in alphabetical order): Linnea Caproni, Preservation Studies Program, University of Arizona William Doelle, Center for Desert Archaeology Anne Goldberg, Department of Anthropology, University of Arizona Andrew Gorski, Preservation Studies Program, University of Arizona Kendall Kroesen, Tucson Audubon Society Larry Marshall, Environmental Education Exchange Linda Mayro, Pima County Cultural Resources Office Bill Robinson, Center for Desert Archaeology Carl Russell, CBV Group J. Homer Thiel, Desert Archaeology, Inc. Photographs contributed by: Adriel Heisey Bob Sharp Gordon Simmons Tucson Citizen Newspaper Tumacácori National Historical Park Maps created by: Catherine Gilman, Desert Archaeology, Inc. Brett Hill, Center for Desert Archaeology James Holmlund, Western Mapping Company Resource information provided by: Arizona Game and Fish Department Center for Desert Archaeology Metropolitan Tucson Convention and Visitors Bureau Pima County Staff Pimería Alta Historical Society Preservation Studies Program, University of Arizona Sky Island Alliance Sonoran Desert Network The Arizona Nature Conservancy Tucson Audubon Society Water Resources Research Center, University of Arizona PREFACE The proposed Santa Cruz Valley National Heritage Area is a big land filled with small details. One’s first impression may be of size and distance—broad valleys rimmed by mountain ranges, with a huge sky arching over all. However, a closer look reveals that, beneath the broad brush strokes, this is a land of astonishing variety. For example, it is comprised of several kinds of desert, year-round flowing streams, and sky island mountain ranges. -

Coronado National Forest Potential Wilderness Area Evaluation Report

United States Department of Agriculture Coronado National Forest Potential Wilderness Area Evaluation Report Forest Service Southwestern Region Coronado National Forest July 2017 Potential Wilderness Area Evaluation Report In accordance with Federal civil rights law and U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) civil rights regulations and policies, the USDA, its Agencies, offices, and employees, and institutions participating in or administering USDA programs are prohibited from discriminating based on race, color, national origin, religion, sex, gender identity (including gender expression), sexual orientation, disability, age, marital status, family/parental status, income derived from a public assistance program, political beliefs, or reprisal or retaliation for prior civil rights activity, in any program or activity conducted or funded by USDA (not all bases apply to all programs). Remedies and complaint filing deadlines vary by program or incident. Persons with disabilities who require alternative means of communication for program information (e.g., Braille, large print, audiotape, American Sign Language, etc.) should contact the responsible Agency or USDA’s TARGET Center at (202) 720-2600 (voice and TTY) or contact USDA through the Federal Relay Service at (800) 877-8339. Additionally, program information may be made available in languages other than English. To file a program discrimination complaint, complete the USDA Program Discrimination Complaint Form, AD-3027, found online at http://www.ascr.usda.gov/complaint_filing_cust.html and at any USDA office or write a letter addressed to USDA and provide in the letter all of the information requested in the form. To request a copy of the complaint form, call (866) 632-9992. Submit your completed form or letter to USDA by: (1) mail: U.S. -

Thesis and Dissertation Index of Arizona Geology to December 1979

Arizona Geological Society Digest, Volume XII, 1980 261 Thesis and Dissertation Index of Arizona Geology to December 1979 From The University of Arizona, Arizona State University, and Northern Arizona University compiled by 1 Gregory R. Wessel Introduction This list is a compilation of all graduate theses and dissertations completed at The University of Arizona, Arizona State University, and Northern Arizona University concerning the geology of Arizona. The list is complete through December 1979. To facilitate the use of this list as a reference, papers are arranged alphabetically into five sec tions on the basis of study area. Four sections cover the four quadrants of the state of Arizona us ing the Gila and Salt River Meridian and Base Line (Fig. 1), and the fifth section contains theses that pertain to the entire state. A thesis or dissertation that includes work in two quadrants is listed under both sections. Those covering subjects or areas outside of the geology of Arizona are omitted. This list was compiled from tabulations of geology theses graciously supplied by each university. Although care was taken to include all theses, some may have been inadvertently overlooked. It is hoped that readers will report any omissions so they may be included in Digest XIII. Digest XIII will contain an update of work 114 113 112 III 110 I 9 completed at Arizona universities, as well as a 37 list of theses and dissertations on Arizona geol ogy completed at universities outside of the state. Grateful acknowledgment is made of the assist 36 ance of Tom L. Heidrick, who inspired the pro- N£ ject and who, with Joe Wilkins, Jr. -

ARIZONA - BLM District and Field Office Boundaries

ARIZONA - BLM District and Field Office Boundaries Bea ve r Beaver Dam D r S Mountains e COLORADO CITY a a i v D m R (! Cottonwood Point sh RAINBOW LODGE u n a Wilderness C d (! I y W Paria Canyon - A W t ge S Sa GLEN CANYON z Y Cow Butte c A l A RED MESA h a a S Lake Powell t e k h n c h h te K Nokaito Bench ! El 5670 l ( s Vermilion Cliffs Mitchell Mesa a o C hi c S E d h S y a e u rt n W i n m Lost Spring Mountain Wilderness KAIByAo B- e s g u Coyote Butte RECREATION AREA O E h S C L r G H C n Wilderness a i l h FREDONIA r l a h ! r s V i ( N o re M C W v e (! s e m L (! n N l a o CANE BEDS a u l e a TES NEZ IAH W n MEXICAN WATER o k I s n k l A w W y a o M O N U M E N T (! W e GLEN CANYON DAM PAGE S C s A W T W G O c y V MOCCASIN h o k (! k W H a n R T Tse Tonte A o a El 5984 T n PAIUTE e n (! I N o E a N s t M y ES k h n s N e a T Meridian Butte l A o LITTLEFIELD c h I Mokaac Mountain PIPE SPRING e k M e o P A r d g R j o E n i (! J I A H e (! r A C r n d W l H a NATIONAL KAIBAB W U C E N k R a s E A h e i S S u S l d O R A c e e O A C a I C r l T r E MONIMENT A L Black Rock Point r t L n n i M M SWEETWATER r V A L L E Y i N c t N e (! a a h S Paiute U Vermilion Cliffs N.M. -

Dpslist Revised April 2018 Gac2.Tb

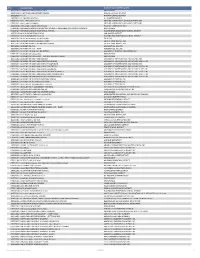

Sierra Club, Angeles Chapter Desert Peaks Section DPS PEAKS LIST 30th Edition, April 2018, 96 Peaks CHANGES from the edition dated April 2003: • Delist three peaks: Argus Peak, Maturango Peak, and Navajo Mountain • Suspend one peak: Edgar Peak INDEX Arc Dome — 6.3 Granite Mtns. #1 — 3.8 Mt. Stirling — 6.6 Rosa Pt. — 4.3 Avawatz Mtns. — 3.1 Granite Mtns. #2 — 4.10 Mt. Tipton — 8.1 Ruby Dome — 6.1 Baboquivari Peak — 8.9 Grapevine Peak — 2.12 Muddy Peak — 6.15 Guardian Angel — 7.2 Big Maria Mtns. — 4.12 Hayford Peak — 6.5 Mummy Mtn. — 6.8 Sandy Pt. — 2.2 Black Butte — 4.7 Humphreys Peak — 8.2 N. Guardian Angel — 7.1 Sentinel Peak — 2.8 Boundary Peak — 1.3 Indianhead — 5.1 Needle Peak — 2.11 Sheephole Mtns. — 3.11 Bridge Mtn. — 6.14 Jacumba Mtn. — 5.3 Nelson Range — 1.12 SIGNAL PEAK — 8.5 Brown Peak — 2.18 Keynot Peak — 1.9 New York Butte — 1.10 Smith Mtn. — 2.16 Canyon Pt. — 2.22 Kingston Peak — 3.2 New York Mtns. — 3.4 Sombrero Peak — 5.2 Castle Dome Peak — 8.6 Kino Peak — 8.7 Nopah Range — 2.21 Spectre Pt. — 4.9 Cerro Pescadores — 9.1 Last Chance Mtn. — 2.1 Old Dad Mtn. — 3.5 Spirit Mtn. — 6.11 Cerro Pinacate — 9.4 Manly Peak — 2.10 Old Woman Mtns. — 3.10 Stepladder Mtns. — 3.12 CHARLESTON PEAK — 6.7 Martinez Mtn. — 4.1 Orocopia Mtns. — 4. Stewart Pt. — 2.19 Chemehuevi Peak — 3.13 McCullough Mtn. -

Tucson and Sabino Canyon for Many Years My Business Travel Took Me to Tucson, Arizona

Tucson and Sabino Canyon For many years my business travel took me to Tucson, Arizona. One of my favorite places in Tucson was to visit when time permitted the Sabino Canyon Recreation Area. The canyon provides an opportunity to hike, picnic or just enjoy the desert scenery. Tucson and Sabino Canyon both have had an interesting historical background. Archaeologists tell us that 12,000 years ago American Indians lived in the Tucson area in the Santa Cruz River Valley. The Hohokam Indians lived there for over 1,000 years beginning in 450AD. They inhabited the Northern Mexico to Central Arizona area. Hohokams used irrigation methods to produce agricultural goods, however their disappearance may have been caused by a lack of food and a change in weather patterns that included both droughts and flooding. <southernarizonaguide.com> Spanish explorers such as Álvar Núñez Cabeza de Vaca, Fray Marcos de Niza, and Francisco Vásquez de Coronado came to Arizona during the 16th century. Some were looking for gold as they traveled from Mexico City. The Zuni Indians were living in the region. <southernarizonaguide.com> During the 17th century, missionaries such as Jesuit Father Eusebio Francisco Kino interacted with the Pima Indians. The Pima Indians had a well‐developed irrigated settlement that they called T'Shuk‐sohn (how Tucson got its name). It meant "Place at the Base of Black Mountain" (later known as Sentinel Peak and now “A” Mountain) which was created by University of Arizona students in 1905 (founded 1885). <southernarizonaguide.com> <cals.arizona.edu> The 18th century was beset with Indian revolts. -

Arizona Geological Survey

GEOLOGIC MAP OF THE SENTINEL-ARLINGTON VOLCANIC FIELD, MARICOPA AND YUMA COUNTIES, ARIZONA Shelby R. Cave Arizona State University Image courtesy of Google Earth Oatman low shield volcano from the central part of the Sentinel-Arlington volcanic field CONTRIBUTED MAP CM-14-A September 2014 Arizona Geological Survey www.azgs.az.gov | repository.azgs.az.gov Arizona Geological Survey M. Lee Allison, State Geologist and Director Printed by the Arizona Geological Survey All rights reserved Printed copies are on sale at the Arizona Experience Store 416 W. Congress, Tucson, AZ 85701 (520.770.3500) [email protected] Arizona Geological Survey visit www.azgs.az.gov. any agency thereof, or any of their employees, makes no warranty, expressed or implied, or assumes any legal liability or responsibility for the accuracy, completeness, or usefulness of imply endorsement by the State of Arizona. ___________________________ CM-14-A, 1:100,000 map scale, 11 p. Arizona Geological Survey Contributed Map CM-14-A Geologic Map of the Sentinel-Arlington Volcanic Field, Maricopa and Yuma Counties, Arizona September 2014 Shelby R. Cave Arizona State University Arizona Geological Survey Contributed Map Series The Contributed Map Series provides non-AZGS authors with a forum for publishing documents concerning Arizona geology. While review comments may have been incorporated, this document does not necessarily conform to AZGS technical, editorial, or policy standards. The Arizona Geological Survey issues no warranty, expressed or implied, regarding the suitability of this product for a particular use. Moreover, the Arizona Geological Survey shall not be liable under any circumstances for any direct, indirect, special, incidental, or consequential damages with respect to claims by users of this product. -

04-05 Annual Report

th Anniversary 2004-2005 Annual Report Our Mission: In partnership with communities, develop resources to promote the positive growth of their children. AzYP 2004-2005 Program Funding SPRANS / DFC…..$829,365 Statement of Financial Position Saddlebrook Rotary / ….$11,546 Assets Arizona Rural Human Services / Tucson Electric Power / Cash and cash equivalents $284,477 Catalina Community Services Grants and contracts receivable $105,314 Total Funding…..$1,746,743.10 City of Tucson …..$25,000 Prepaid expenses and deposits $5,542 Pima County…..$33,320 Furniture and equipment, at cost, net of $46,474 accumulated depreciation of $70,114 $441,807 ADHS…..$160,000 Liabilities and Net Assets CPSA…..$166,502 Accounts payable $37,600 CPSA - Tohono…..$225,000 Accrued expenses $47,929 Governor’s Office…..$296,010 Total liabilities $85,529 Net assets: unrestricted $356,278 $441,807 Statement of Activities Year Ended June 30, 2005 Temporarily Temporarily Unrestricted Restricted Total Unrestricted Restricted Total Revenue gains and other support Net assets released from restrictions: Grants and contracts Satisfaction of program U.S. Department of Health and $563,257 $563,257 restrictions Human Services $1,394,613 ($1,394,613) $0 Community Partnership of $391,500 $391,500 Southern Arizona Total revenue, State of Arizona $377,538 $377,538 gains and other income $1,706,884 $0 $1,706,884 Pima County, Arizona $33,320 $33,320 City of Tucson $24,998 $24,998 Expenses: Other grants and contracts $4,000 $4,000 Contract expenses $1,442,686 $1,442,686 Total grants -

The Sentinel-Arlington Volcanic Field, Arizona by Shelby Renee Cave A

The Sentinel-Arlington Volcanic Field, Arizona by Shelby Renee Cave A Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy Approved April 2015 by the Graduate Supervisory Committee: Amanda Clarke, Chair Donald Burt Stephen Reynolds Mark Schmeeckle Steven Semken ARIZONA STATE UNIVERSITY May 2015 ABSTRACT The Sentinel-Arlington Volcanic Field (SAVF) is the Sentinel Plains lava field and associated volcanic edifices of late Cenozoic alkali olivine basaltic lava flows and minor tephra deposits near the Gila Bend and Painted Rock Mountains, 65 km-100km southwest of Phoenix, Arizona. The SAVF covers ~600 km 2 and consists of 21+ volcanic centers, primarily low shield volcanoes ranging from 4-6 km in diameter and 30-200 m in height. The SAVF represents plains-style volcanism, an emplacement style and effusion rate intermediate between flood volcanism and large shield- building volcanism. Because of these characteristics, SAVF is a good analogue to small-volume effusive volcanic centers on Mars, such as those seen the southern flank of Pavonis Mons and in the Tempe Terra region of Mars. The eruptive history of the volcanic field is established through detailed geologic map supplemented by geochemical, paleomagnetic, and geochronological analysis. Paleomagnetic analyses were completed on 473 oriented core samples from 58 sites. Mean inclination and declination directions were calculated from 8-12 samples at each site. Fifty sites revealed well-grouped natural remanent magnetization vectors after applying alternating field demagnetization. Thirty-nine sites had reversed polarity, eleven had normal polarity. Fifteen unique paleosecular variation inclination and declination directions were identified, six were represented by more than one site with resultant vectors that correlated within a 95% confidence interval. -

Detrital Zircon Provenance and Paleogeography of the Pahrump

Precambrian Research 251 (2014) 102–117 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Precambrian Research jo urnal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/precamres Detrital zircon provenance and paleogeography of the Pahrump Group and overlying strata, Death Valley, California a,∗ b a c Robert C. Mahon , Carol M. Dehler , Paul K. Link , Karl E. Karlstrom , d George E. Gehrels a Idaho State University, Department of Geosciences, 921 South 8th Avenue, Stop 8072, Pocatello, ID 83209-8072, United States b Utah State University, Department of Geology, 4505 Old Main Hill, Logan, UT 84322-4505, United States c University of New Mexico, Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences, MSCO3-2040, Albuquerque, NM 87131, United States d University of Arizona, Department of Geosciences, 1040 East 4th Street, Tucson, AZ 85721, United States a r a t i b s c l t r e a i n f o c t Article history: The Mesoproterozoic and Neoproterozoic Pahrump Group of Death Valley, California spans ca. Received 21 January 2014 1300–635 Ma and provides a >500 million-year record of geologic events in southwestern Laurentia. Received in revised form 28 April 2014 The strata analyzed include preserved sequences separated by unconformities recording syn-Rodinia Accepted 9 June 2014 basin development (Crystal Spring Formation); Rodinia stability; regional extension culminating in Neo- Available online 19 June 2014 proterozoic rifting of the Laurentian margin of Rodinia (Horse Thief Springs through Johnnie Formations); and multiple phases of glacial sedimentation and subsequent cap carbonate deposition (Kingston Peak Keywords: Formation and Noonday Dolomite). U-Pb detrital zircon analyses were conducted on samples from the Rodinia Proterozoic entire Pahrump Group and the Noonday Dolomite in the southeastern Death Valley region (20 samples, 1945 grains) to further constrain hypotheses for regional basin development during the development of Pahrump Group Death Valley the southwestern Laurentian margin. -

List of Schools and CTDS

CTDS SCHOOL NAME DISTRICT OR CHARTER HOLDER 108731101 A CHILD'S VIEW SCHOOL-CLOSED UNAVAILABLE 120201114 A J MITCHELL ELEMENTARY SCHOOL NOGALES UNIFIED DISTRICT 100206038 A. C. E. MARANA UNIFIED DISTRICT 118720001 A+ CHARTER SCHOOLS A+ CHARTER SCHOOLS 078707202 AAEC - PARADISE VALLEY ARIZONA AGRIBUSINESS & EQUINE CENTER, INC. 078993201 AAEC - SMCC CAMPUS ARIZONA AGRIBUSINESS & EQUINE CENTER, INC. 130201016 ABIA JUDD ELEMENTARY SCHOOL PRESCOTT UNIFIED DISTRICT 078689101 ABRAHAM LINCOLN PREPARATORY SCHOOL: A CHALLENGE FOUNDATION ACADEMY UNAVAILABLE 070406167 ABRAHAM LINCOLN TRADITIONAL SCHOOL WASHINGTON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL DISTRICT 100220119 ACACIA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL VAIL UNIFIED DISTRICT 070406114 ACACIA ELEMENTARY SCHOOL WASHINGTON ELEMENTARY SCHOOL DISTRICT 108506101 ACADEMY ADVENTURES MIDTOWN ED AHEAD 108717103 ACADEMY ADVENTURES MID-TOWN EDUCATIONAL IMPACT, INC. 108717101 ACADEMY ADVENTURES PRIMARY SCHOOL EDUCATIONAL IMPACT, INC. 108734001 ACADEMY DEL SOL ACADEMY DEL SOL, INC. 108734002 ACADEMY DEL SOL - HOPE ACADEMY DEL SOL, INC. 088704201 ACADEMY OF BUILDING INDUSTRIES ACADEMY OF BUILDING INDUSTRIES, INC. 078604101 ACADEMY OF EXCELLENCE UNAVAILABLE 078604004 ACADEMY OF EXCELLENCE - CENTRAL ARIZONA-CLOSED UNAVAILABLE 108713101 ACADEMY OF MATH AND SCIENCE ACADEMY OF MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE, INC. 078242005 ACADEMY OF MATH AND SCIENCE AVONDALE ACADEMY OF MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE SOUTH, INC. 078270001 ACADEMY OF MATH AND SCIENCE CAMELBACK ACADEMY OF MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE, INC. 078242002 ACADEMY OF MATH AND SCIENCE DESERT SKY ACADEMY OF MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE SOUTH, INC. 078242004 ACADEMY OF MATH AND SCIENCE GLENDALE ACADEMY OF MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE SOUTH, INC. 078242003 ACADEMY OF MATH AND SCIENCE PEORIA ADVANCED ACADEMY OF MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE SOUTH, INC. 078242006 ACADEMY OF MATH AND SCIENCE SOUTH MOUNTAIN ACADEMY OF MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE SOUTH, INC. 078242001 ACADEMY OF MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE SOUTH ACADEMY OF MATHEMATICS AND SCIENCE SOUTH, INC.