Sample Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Creative Process

The Creative Process THE SEARCH FOR AN AUDIO-VISUAL LANGUAGE AND STRUCTURE SECOND EDITION by John Howard Lawson Preface by Jay Leyda dol HILL AND WANG • NEW YORK www.johnhowardlawson.com Copyright © 1964, 1967 by John Howard Lawson All rights reserved Library of Congress catalog card number: 67-26852 Manufactured in the United States of America First edition September 1964 Second edition November 1967 www.johnhowardlawson.com To the Association of Film Makers of the U.S.S.R. and all its members, whose proud traditions and present achievements have been an inspiration in the preparation of this book www.johnhowardlawson.com Preface The masters of cinema moved at a leisurely pace, enjoyed giving generalized instruction, and loved to abandon themselves to reminis cence. They made it clear that they possessed certain magical secrets of their profession, but they mentioned them evasively. Now and then they made lofty artistic pronouncements, but they showed a more sincere interest in anecdotes about scenarios that were written on a cuff during a gay supper.... This might well be a description of Hollywood during any period of its cultivated silence on the matter of film-making. Actually, it is Leningrad in 1924, described by Grigori Kozintsev in his memoirs.1 It is so seldom that we are allowed to study the disclosures of a Hollywood film-maker about his medium that I cannot recall the last instance that preceded John Howard Lawson's book. There is no dearth of books about Hollywood, but when did any other book come from there that takes such articulate pride in the art that is-or was-made there? I have never understood exactly why the makers of American films felt it necessary to hide their methods and aims under blankets of coyness and anecdotes, the one as impenetrable as the other. -

Expressionism and Modernism in the American Theatre: Bodies, Voices, Words Julia A

Cambridge University Press 0521847478 - Expressionism and Modernism in the American Theatre: Bodies, Voices, Words Julia A. Walker Frontmatter More information Expressionism and Modernism in the American Theatre Although often dismissed as a minor offshoot of the better-known German movement, expressionism on the American stage represents a critical phase in the development of American dramatic modernism. Situating expressionism within the context of early twentieth-century American culture, Walker demonstrates how playwrights who wrote in this mode were responding both to new communica- tions technologies and to the perceived threat they posed to the embodied act of meaning. At a time when mute bodies gesticulated on the silver screen, ghostly voices emanated from tin horns, and inked words stamped out the personality of the hand that composed them, expressionist playwrights began to represent these new cultural experiences by disarticulating the theatrical languages of bodies, voices, and words. In doing so, they not only innovated a new dramatic form, but re- defined playwriting from a theatrical craft to a literary art form, heralding the birth of American dramatic modernism. julia a. walker is Assistant Professor of English and the Unit for Criticism and Interpretive Theory,University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign. She has published articles in the Journal of American Drama and Theatre, Nineteenth Century Theatre, and the Yale Journal of Criticism in addition to several edited volumes. © Cambridge University Press www.cambridge.org Cambridge University Press 0521847478 - Expressionism and Modernism in the American Theatre: Bodies, Voices, Words Julia A. Walker Frontmatter More information CAMBRIDGE STUDIES IN AMERICAN THEATRE AND DRAMA General Editor Don B. -

ABSTRACT Title of Document: from the BELLY of the HUAC: the RED PROBES of HOLLYWOOD, 1947-1952 Jack D. Meeks, Doctor of Philos

ABSTRACT Title of Document: FROM THE BELLY OF THE HUAC: THE RED PROBES OF HOLLYWOOD, 1947-1952 Jack D. Meeks, Doctor of Philosophy, 2009 Directed By: Dr. Maurine Beasley, Journalism The House Un-American Activities Committee, popularly known as the HUAC, conducted two investigations of the movie industry, in 1947 and again in 1951-1952. The goal was to determine the extent of communist infiltration in Hollywood and whether communist propaganda had made it into American movies. The spotlight that the HUAC shone on Tinsel Town led to the blacklisting of approximately 300 Hollywood professionals. This, along with the HUAC’s insistence that witnesses testifying under oath identify others that they knew to be communists, contributed to the Committee’s notoriety. Until now, historians have concentrated on offering accounts of the HUAC’s practice of naming names, its scrutiny of movies for propaganda, and its intervention in Hollywood union disputes. The HUAC’s sealed files were first opened to scholars in 2001. This study is the first to draw extensively on these newly available documents in an effort to reevaluate the HUAC’s Hollywood probes. This study assesses four areas in which the new evidence indicates significant, fresh findings. First, a detailed analysis of the Committee’s investigatory methods reveals that most of the HUAC’s information came from a careful, on-going analysis of the communist press, rather than techniques such as surveillance, wiretaps and other cloak and dagger activities. Second, the evidence shows the crucial role played by two brothers, both German communists living as refugees in America during World War II, in motivating the Committee to launch its first Hollywood probe. -

The Political History of Classical Hollywood: Moguls, Liberals and Radicals in The

The political history of Classical Hollywood: moguls, liberals and radicals in the 1930s Professor Mark Wheeler, London Metropolitan University Introduction Hollywood’s relationship with the political elite in the Depression reflected the trends which defined the USA’s affairs in the interwar years. For the moguls mixing with the powerful indicated their acceptance by America’s elites who had scorned them as vulgar hucksters due to their Jewish and show business backgrounds. They could achieve social recognition by demonstrating a commitment to conservative principles and supported the Republican Party. However, MGM’s Louis B. Mayer held deep right-wing convictions and became the vice-chairman of the Southern Californian Republican Party. He formed alliances with President Herbert Hoover and the right-wing press magnate William Randolph Hearst. Along with Hearst, Will Hays and an array of Californian business forces, ‘Louie Be’ and MGM’s Production Chief Irving Thalberg led a propaganda campaign against Upton Sinclair’s End Poverty in California (EPIC) gubernatorial election crusade in 1934. This form of ‘mogul politics’ was characterized by the instincts of its authors: hardness, shrewdness, autocracy and coercion. 1 In response to the mogul’s mercurial values, the Hollywood community pursued a significant degree of liberal and populist political activism, along with a growing radicalism among writers, directors and stars. For instance, James Cagney and Charlie Chaplin supported Sinclair’s EPIC campaign by attending meetings and collecting monies. Their actions reflected the economic, social and political conditions of the era, notably the collapse of US capitalism with the Great Depression, the New Deal, the establishment of trade unions, and the emigration of European political refugees due to Nazism. -

An Examination of Three Attorneys Who Represented

UCLA UCLA Entertainment Law Review Title Three Brave Men: An Examinantion of Three Attorneys Who Represented the Hollywood Nineteen in the House Un-American Activities Committee Hearings in 1947 and the Consequences They Faced Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/7mq6r2rb Journal UCLA Entertainment Law Review, 6(2) ISSN 1073-2896 Author Bose, Erica Publication Date 1999 DOI 10.5070/LR862026987 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Three Brave Men: An Examinantion of Three Attorneys Who Represented the Hollywood Nineteen in the House Un- American Activities Committee Hearings in 1947 and the Consequences They Faced Erica Bose* I. INTRODUCTION On September 30, 1952 an attorney appeared before the House Subcommittee on Un-American Activities in Los Angeles as an extremely hostile witness. Ben Margolis, prominent labor lawyer and well-known radical, vehemently refused to answer nearly every question Chairman John S. Wood put forth to him. When asked if he knew Edward Dmytryk, one of the first "unfriendly witnesses" to appear before the House Un-American Activities Committee (H.U.A.C.) in Washington in 1947 who later recanted and named names, Margolis responded by stating, "Unfortunately he has become a member of your stable. I refuse to answer on the ground that it would tend to degrade me by association with any such person."' When "J.D. candidate, UCLA School of Law, 2001. I would like to express my sincere thanks to Ben Margolis, Patricia Bosworth, Ellenore Bogigian Hittelman, Ring Lardner, Jr., Ann Fagan Ginger, and Michael O'Malley. Without their help, I would never have been able to write this comment. -

4 11"C.� C(5-,,I/V-V--"-.1--• - Caa El-Dt4- �4 I K -

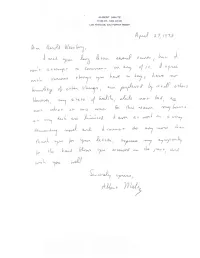

ALBERT MALTZ 9120 ST. IVES DRIVE LOS ANGELES, CALIFORNIA 90069 A, I g 5 '73 wtereik des, (Li- I • 3 3 rt....J. -I- 1/4 11"C. C(5-,,i/v-v--"-.1--• - cAA el-dt4- 4 i k - , d- c FR wut 1— (TO. d / Iti-43we-sfe-N i fIrsfl 4. --(i. q 1..),I,, ..,,,,„_ --(.-_, Fn. (1., du a...„,„i Zw-LA-4 s A,,,,r-..- LA.L ik h k 'F- c..." L kva...-a , v.rErt 4 c-,.. A 14. GLAA ..), 4-ed J zi.,,e-y-. (k R_ v' t7 ce.,_444 .L.„. I vLA7 ,7721la, 4— tt,,a. (-1L/—t 4 cr-c- ii(F„ Witzit lowed began to disintegrate with the discovery those they accused of being Communists.' Robert The Hollywood 10 recalled in 1957 that the "Robert Rich" who won an Vaughn, who came to prominence as "The Man Academy Award for "The Brave One" was actually from 1.1.N,C.L.E.," has published his doctoral dtseer- Dalton Trumbo, perhaps the most rambunctious of tatleri, 3 study of thaw business blacklisting, as a the original 10, who used to earn 54,000 a week hook entitled "Only Victims." Stefan Ranier, aaso- To name before he was blacklisted. And yet many of abate editor of Time magazine, has written the the surviving victims of the blacklist—whether forthcoming "A Journal of the Plague Years," they are successful like Ring tardner Jr., who which, Like the Defoe novel of the same name, or not won an Oscar for "IWA"VH," or are on hard times shows how a disease—blacklisting—can infect an Like Alvah Bessie, who never made it back to entire society. -

Active Viewers Guide Trumbo 1

Active Viewers Guide Trumbo 1. Step 1 – Let’s view the trailer to the 2015 film Trumbo (located at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=e9HbaaSukm4). 2. Step 2 – Please locate the Pre-Viewing: About Trumbo for class review. 3. Step 3 – We will now view the film, only to stop at Trumbo’s HUAC testimony (to view the videos linked below and to read the note below it), and we will also stop each time we are introduced to the characters that are found on the Cast of Trumbo page. a. We will stop to view a short history of HUAC located at https://youtu.be/FSRaDEUGRkM, and Dalton Trumbo’s HUAC testimony (located at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1zGHZPwImHI)y at that point in the film. Prior to watching the video we will read: Yes, Trumbo was a communist. He even openly tells his daughter about it in the movie, but he believes that shouldn't determine whether he should work or not. In the actual footage above, you can see his 1947 testimony in front of the House Committee on Un-American Activities where he was held in contempt of Congress for not admitting to being a communist. In the film's press notes, Niki said that being a communist in the '40s "meant that you were pro-labor and anti-Jim Crow, and you fought for civil rights for African Americans," she said. "It had nothing to do with Russia and everything to do with how an already great country could improve itself." Trumbo ended up going to prison for 11 months because of his beliefs. -

A Critical Review of the 1947 HUAC Hearings and the Hollywood Ten

Dublin Business School A Critical Review of the 1947 HUAC Hearings and the Hollywood Ten 1449707 By Emmet Kenny 5/25/2012 Acknowledgements I first want to sincerely thank my supervisor for this dissertation, Doctor Barnaby Taylor whose superb guidance, really helpful input, encouragement and overall support were invaluable to the creation of this dissertation. From start to finish he pushed me and allowed me to gain a much greater understanding and appreciation for film in general. I would also like to thank all the other lecturers I have had throughout my three years in DBS doing this course. Connor Murphy, Matt Nolan, Clare Dix, Kenny Leigh and Dave Gunning all played a huge part in helping me to fully experience the medium of film and all its aspects. Finally, I would like to offer my best regards and blessings to all of those who have supported me in any respect, mainly my mother Maura and my two sisters, Sheena and Avril for their continued support throughout the years 1 This dissertation looks at how in the aftermath of the Second World War, Hollywood became a prime target for the government forces of the conservative right. It shows how these forces through the House committee for Un-American Activities used the heightened public fear of the growing power of communist Russia as an opportunity to take down their political enemies on the left side of American politics. It will also look at the individuals who became their prime targets and the reasons behind why each of them was targeted. Finally this dissertation will show how the 1947 hearings affected each of their lives and especially careers. -

The Hollywood Ten

HUAC The Hollywood Ten InIn 1947,1947, CongressCongress setset upup thethe HOUSEHOUSE COMMITTEECOMMITTEE ONON UN-AMERICANUN-AMERICAN ACTIVITIESACTIVITIES (HUAC).(HUAC). It’sIt’s purposepurpose waswas toto looklook forfor CommunistsCommunists bothboth insideinside && outsideoutside government.government. HUAC House Un-American Activities Committee Congressional committee to find Communists. Focused more on Hollywood. The HUAC concentrated on the movie industry because of suspected Communist influences in Hollywood. Playwright Arthur Miller testifies before HUAC Many people were brought before HUAC. Some agreed that there had been Communist infiltration of the movie industry. They informed on others to save themselves. Hollywood in the 1950s A number of actors had been Communists in the 1930s. The US govt. had encouraged films that were pro-Soviet during WWII. Now they were out for the actors / writers / directors of “un- American” shows. In 1947, the House of Un-American Activities Committee (HUAC), which was chaired by J. Parnell Thomas, started an investigation into the Hollywood Motion Picture Industry. The HUAC interviewed 41 people who were working in Hollywood. These people were interviewed voluntarily and were known as friendly witnesses. During their interviews, they named nineteen people who they said held left-wing views. Ten of those people refused to answer any questions during the hearings thus became known as the Hollywood Ten. They were Alvah Bessie, Herbert Biberman, Lester Cole, Edward Dmytryk, Ring Lardner Jr., John Howard Lawson, Albert Maltz, Samuel Ornitz, Adrian Scott and Dalton Trumbo. HollywoodHollywood 1010 The ten men claimed that the First Amendment of the United States Constitution gave them the right to refuse to answer questions about their beliefs. -

Theory and Technique of Playwriting and Screenwriting

Theory and Technique of Playwriting and Screenwriting John Howard Lawson Theory and Technique of Playwriting and Screenwriting by John Howard Lawson is presented here thanks to the generosity of Jeffrey Lawson and Susan Amanda Lawson. © All rights reserved. Reproduction for commercial use is prohibited. August 2014 Revised March 2020 John Howard Lawson’s Theory and Technique of Playwriting was published in 1936. Thirteen years later he added several chapters about the history and craft of filmmaking, and presented to the world Theory and Technique of Playwriting and Screenwriting (G.P. Putnam’s), what many consider to be one of the finest books ever written about dramatic construction. Long out-of-print, this unabridged online version has been scanned from an original copy. All that differs from the 1949 edition is the removal of the “Check List of Films” and the index. New pagination has been introduced. Additionally, included below is the introduction to Lawson’s 1960 edition of Theory and Technique of Playwriting (Hill and Wang). PDFs of Lawson’s Film: The Creative Process (second edition 1967, Hill and Wang) and his Theory and Technique of Playwriting (1960, Hill and Wang), as well as a fifteen-page selection of extracts from Theory and Technique of Playwriting and Screenwriting, summarising Lawson’s ideas on dramatic construction, are available at www.johnhowardlawson.com. For details of Lawson’s life and work, readers are directed to Gerald Horne’s The Final Victim of the Blacklist: John Howard Lawson, Dean of the Hollywood Ten (University of California Press, 2006). For analysis of his many plays and screenplays see Jonathan L. -

Hollywood Modernism: Film and Politics in the Age of the New Deal

Introduction Taking Hollywood Seriously he purpose of this study is to connect the historical develop- ment of Hollywood’s cinematic style with the social and politi- cal history of the Hollywood community. Substantial elements of Hollywood classical cinema are the result of a political and T esthetic negotiation engaging European anti-fascist refugees, radical urban American intellectuals, and studio executives from the early 1930s to the late 1940s. This negotiation was an integral part of the intellectual and political debates of the New Deal era, and it left a profound mark on some of the films Hollywood made in this period. An effort to contextualize Hollywood and its films plays a crucial role in this work. In the 1930s and 1940s, Hollywood was not a “Baghdad by the sea”1 separated from the rest of the United States. Nor were its films a simple reflection of the commercial nature of the studio system. Rather, the Hollywood community was animated by many of the same debates that were the center of the political and intellectual discourse in New York. Like their colleagues back East, in fact, intellectuals in Hollywood were part of the leftist political culture of the 1930s, and they discussed the democratization of modernism, its politicization, and the formulation of a mass-marketed progressive culture capable of dealing with the political issues of the day. This study identifies, chronicles, and interprets the social, intellectual, and esthetic history of what I call Hollywood 1 2 Introduction democratic modernism. It examines its emergence, the transformations brought about by World War II, and its demise in the aftermath of the conflict. -

Testimony of Jack L. Warner

Testimony of Jack L. Warner Jack Warner (1892-1978) entered the motion picture industry at the age of eleven, when he and his three older brothers opened a movie theater in New Castle, Pennsylvania. By the 1940s Jack Warner was one of the most powerful men in Hollywood, with his studios producing popular cartoons as well as blockbuster films. Below he answers questions about the 1943 film, Mission to Moscow, in which the U.S. ambassador travels to Russia and comes back a supporter of Stalinism _________________________________________________________________ Mr. WARNER: Ideological termites have burrowed into many American industries, organizations, and societies. Wherever they may be, I say let us dig them out and get rid of them. My brothers and I will be happy to subscribe generously to a pest-removal fund. We are willing to establish such a fund to ship to Russia the people who don’t like our American system of government and prefer the communistic system to ours. That’s how strongly we feel about the subversives who want to overthrow our free American system. If there are Communists in our industry, or any other industry, organization, or society who seek to undermine our free institutions, let’s find out about it and know who they are. Let the record be spread clear, for all to read and judge. The public is entitled to know the facts. And the motion- picture industry is entitled to have the public know the facts. Our company is keenly aware of its responsibilities to keep its product free from subversive poisons.