“Bosman”: Are Competition Exemptions Admissible for Football?

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Arsenal Holdings Plc Financial Highlights Directors, Officers and Advisers

CONTENTS FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS page 3 DIRECTORS, OFFICERS & ADVISERS page 4 CHAIRMAN’S REPORT page 5 EMIRATES STADIUM page 14 REVIEW OF THE 2004/2005 SEASON page 15 CHARITY OF THE SEASON page 20 ARSENAL IN THE COMMUNITY page 21 DIRECTORS’ REPORT page 22 FINANCIAL STATEMENTS Corporate Governance page 24 Remuneration Report page 25 Independent Auditors’ Report page 26 Consolidated Profit and Loss Account page 27 Balance Sheets page 28 Consolidated Cash Flow Statement page 29 Notes to the Accounts page 30 FIVE YEAR SUMMARY page 49 NOTICE OF ANNUAL GENERAL MEETING page 50 AGM VOTING FORM page 51 FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS 2005 2004 Group turnover £m 138.4 156.9 Group operating profit before player trading and exceptional costs £m 32.6 36.2 Profit before taxation £m 19.3 10.6 Earnings per share £ 138.91 138.29 Group Turnover Group operating profit before player trading and exceptionals £m £m £m 180 40 160 35 140 30 120 25 100 20 80 15 60 10 40 5 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 Wage Cost as % of Group turnover Investment in fixed assets per annum %£m 70 120 65 100 60 80 55 60 50 40 45 20 40 0 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 2001 2002 2003 2004 2005 3 ARSENAL HOLDINGS PLC FINANCIAL HIGHLIGHTS DIRECTORS, OFFICERS AND ADVISERS LIFE VICE PRESIDENT BANKERS C E B L Carr Royal Bank of Scotland plc 62/63 Threadneedle Street DIRECTORS London P D Hill-Wood EC2R 8LA Lady Nina Bracewell-Smith R C L Carr Barclays Bank plc D B Dein Holloway & Kingsland K G Edelman Business Centre D D Fiszman London K J Friar OBE E8 2JX Sir Roger Gibbs REGISTRARS MANAGER Capita IRG plc A Wenger OBE The Registry 34 Beckenham Road SECRETARY Beckenham D Miles Kent BR3 4TU GROUP CHIEF ACCOUNTANT S W Wisely ACA REGISTERED OFFICE Arsenal Stadium AUDITORS Avenell Road Deloitte & Touche LLP Highbury Chartered Accountants London London N5 1BU SOLICITORS COMPANY REG. -

Ma Vie, Mon Oeuvre, Mon Cul (Philoumiha)

Ma Vie, Mon Oeuvre, Mon Cul (philoumiha) Ceci est une fiction. Toute ressemblance avec des personnes de la vie réelle ou avec des faits historiques avérés serait complètement involontaire de ma part. Mardi 17 juin 2008, abords du Stade de Suisse, Berne. - C'est vraiment dommage, on fait un gros match. Je suis vraiment fier de mes joueurs. On a pas eu beaucoup de réussite mais y'avait quand même des choses interessantes. - Mais quand même, perdre 6-1 face à la Pologne alors qu'on attendait une réaction d'orgueil de la part de l'équipe, ca fait beaucoup. - Libre à vous de voir les choses comme ca. De toute facon, c'est facile de critiquer. Mais je maintiens que je suis content de la performance des garcons. On a pas eu de chance. Y'a qu'à voir les stats du match. 1 tir pour nous, 1 but. 27 tirs pour eux, 6 buts. Ca nous fait du 100%, pas eux. Les mathématiques et les astres ne mentent jamais. - Vous avez des regrets sur ce match? - Non, on a fait ce qu'il fallait. Faut dire aussi que l'arbitre a pas été très loyal. Regardez à 10 minutes de la fin, Machinski fait une faute qui mérite un jaune. Et l'arbitre sort pas le carton. Dans ces conditions, pas facile de gagner. - Votre avenir, c'est quoi? - En ce moment, je pense juste à me marier. D'ailleurs Estelle, ma mie, ma douce, ma bitch, veux-tu m'epousailler? T.Roland: Hé Hé Hé Ho (son rire à la con). -

The Relationship Between EU Law and CAS Jurisprudence

The relationship btw EU law and CAS From the Bosman Ruling to the ISU case(s) By Alessandro Oliverio Law School of Chukyo University (JPN) January 2018 The relationship btw EU Law and CAS 1 The sources of sports law (Olympic Charter) IOC IFs NOCs NFs Clubs – Leagues Athletes WADA CAS January 2018 The relationship btw EU Law and CAS 2 The CAS – main features History established in 1984 Before 1995: few cases x year 1993: SFT Gundel ruling: recognition as independent and impartial tribunal / legitimacy of awards 1994: CAS reform: creation of ICAS (International Council of Arbitration for Sport) 1995: ECJ Bosman ruling / binding arbitration clauses in the SGBs’ statutes 2000: ad-hoc division at the Olympics 2003: 100 cases x year (adoption of WADA code) 2016: 500 cases x year Procedure Arbitration clause Ordinary Division (disputes of commercial/contractual nature) Appeal Division (decisions of SGBs) Supreme Court of World Sport Closed list of arbitrators (369). Japan: 2 Switzerland: 29 Panel of 3 arbitrators Time limits: R49 21 days – R59 3 months Binding award. Challenge (annulment) before SFT for incompability with public policy January 2018 The relationship btw EU Law and CAS 3 The EU instituions in brief (1) The EU Parliament: Directly-elected EU body with legislative, supervisory, and budgetary responsibilities White Paper on sport (2007): Its overall objective is to give strategic orientation on the role of sport in Europe, to encourage debate on specific problems, to enhance the visibility of sport in EU policy-making and to raise public awareness of the needs and specificities of sector. -

The Gooner Survey Results 2013

THE GOONER SURVEY RESULTS 2013 PART 1 – SEASON 2012-13 Arsenal Player of the Season 2012/13 Best Arsenal Goal 2012/13 1st Choice 2nd Choice 1. Podolski v Montpellier (H) 1. Santi Cazorla 63% 26% 2. Walcott’s 3rd v Newcastle (H) 2. Laurent Koscielny 22% 39% 3. Cazorla v West Ham (A) 3. Theo Walcott 5% 19% 4. Gibbs v Swansea (A - FA Cup) 4. Jack Wilshere 2% 5% 5. Mertesacker v Spurs (H) Other 8% 11% 6. Podolski v West Ham (H) Most Disappointing Arsenal Player 2012/13 1st Choice 2nd Choice 1. Thomas Vermaelen 60% 25% 2. Bacary Sagna 20% 38% 3. Wojciech Szczesny 4% 15% Other 16% 22% Most Improved Arsenal Player in last 12 months 1. Ramsey 46% 2. Laurent Koscielny 30% 3. Theo Walcott 13% Whilst recognising that the summer transfer Other 11% dealings will play a large part in how we fare next season, at this point in time how optimistic are you about our prospects of competing for the Best Team Performance 2012/13 Premier League title in 2013-14? Extremely Optimistic 6% 1. 2-0 v Bayern Munich (A) 44% Quite Optimistic 35% 2. 5-2 v Spurs (H) 24% Unsure 25% 3. 2-0 v Liverpool (A) 17% Quite pessimistic 21% 4. 7-3 v Newcastle (H) 4% Extremely pessimistic 13% Other 11% Whilst accepting the two are not mutually Worst Team Performace exclusive, which of the following achievements do you regard as being most important? 1. 0-1 v Blackburn (H) 32% 2. 1-1 v Bradford (A) 31% Qualifying for the Champions League 59% 3. -

Evidence from the European Football Mar Et

Taxation and International Migration of Superstars: Evidence from the European Football Market∗ Henrik Jacobsen Kleven, London School of Economics Camille Landais, Stanford University Emmanuel Saez, UC Berkeley June 2011 Abstract This paper analyzes the effects of top earnings tax rates on the international migration of football players in Europe. We construct a panel data set of top earnings tax rates, football player careers, and club performances in the first leagues of 14 European coun- tries since 1985. We identify the effects of top earnings tax rates on migration using a number of tax and institutional changes: (a) the 1995 Bosman ruling which liberalized the European football market, (b) top tax rate reforms within countries, and (c) special tax schemes offering preferential tax rates to immigrant football players. We start by present- ing reduced-form graphical evidence showing large and compelling migration responses to country-specific tax reforms and labor market regulation. We then develop a multinomial regression framework to exploit all sources of tax variation simultaneously. Our results show that (i) the overall location elasticity with respect to the net-of-tax rate is positive and large, (ii) location elasticities are extremely large at the top of the ability distribu- tion but negative at the bottom due to ability sorting effects, and (iii) cross-tax effects of foreign players on domestic players (and vice versa) are negative and quite strong due to displacement effects. ∗We would like to thank Raj Chetty, Caroline Hoxby, Larry Katz, Wojciech Kopczuk, Claus Kreiner, Thomas Piketty, James Poterba, Guttorm Schjelderup, Dan Silverman, Joel Slemrod, and numerous seminar participants for helpful comments and discussions. -

The Future of Football in the European Union – from a Legal Point of View

The Future of Football in the European Union – from a Legal Point of View Marie Kronberg University of Passau, Germany Publicerad på Internet, www.idrottsforum.org/articles/kronberg/kronberg101013.html (ISSN 1652–7224), 2010–10–13 Copyright © Marie Kronberg 2010. All rights reserved. Except for the quotation of short passages for the purposes of criticism and review, no part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the author. It’s often said, about one thing or the other, that if it didn’t exist, someone would invent it. This applies very much to sports, although it is clearly difficult to reason counterfactually about a phe- nomenon that so permeates the daily lives of all people. So let’s avoid imagining a world with- out sports, and restrict this speculation to a supposed introduction of sports in society in 2010. How would that work? – Like so much else today, it would probably be a project introduced from above, e.g. in Europe at EU level, with directives to member states to adopt laws that initiate and regulate this new form of entertainment. Much of what we today take for granted in terms of recreational and competitive sports would probably never come into being, such as sports where the participants might get hurt (like boxing), or where the environment might suffer (such as motor racing), or contests between nations – international competitions would most likely take the form of the Ryder Cup, extrapolated to the global level, that is to say that Europe will compete against the U.S. -

David Held, Anthony Mcgrew, David Goldblatt, Jonathan Perraton

EUROPEANIZATION AND THE EMERGENCE OF A EUROPEAN SOCIETY Juan Díez Medrano 2008/12 Juan Díez Medrano Institut Barcelona d'Estudis Internacionals (IBEI) / Universitat de Barcelona. Research Program Coordinator “Networks and Institutions in a Global Society” at IBEI, and Professor of the University of Barcelona at the Dept. of Department of Sociological Theory, Philosophy of Law and Methodology for Social Sciences [email protected] / [email protected] ISSN: 1886-2802 IBEI WORKING PAPERS 2008/12 Europeanization and the Emergence of a European Society © Juan Díez Medrano © IBEI, de esta edición Edita: CIDOB edicions Elisabets, 12 08001 Barcelona Tel. 93 302 64 95 Fax. 93 302 21 18 E-mail: [email protected] URL: www.cidob.org Depósito legal: B-21.147-2006 ISSN:1886-2802 Imprime: Color Marfil, S.L. Barcelona, January 2008 EUROPEANIZATION AND THE EMERGENCE OF A EUROPEAN SOCIETY Juan Díez Medrano Abstract: This article examines the European integration process from a sociological perspective, where the main focus is the examination of the social consequences of the integration process. The European Union has advanced significantly in the economic, social, and political integra- tion processes. This has resulted in a rapid Europeanization of behavior. There has hardly been any progress, however, toward the development of European social groups. This article exam- ines the causes of this lag and concludes that it is highly unlikely that in the middle run there be significant progress toward the Europeanization of society. Key words: European integration, Identity, Sociology. -3- 1. Introduction orking Papers The literature on European integration of the last fifty years has focused almost exclusively on the process of economic and political institutionalization. -

P20 Layout 1

Serena, Sharapova Windies rout again on Miami Bangladesh collision course WEDNESDAY, MARCH 26, 201417 18 Brazil beckons Pakistan’s street kid footballers Page 19 OLD TRAFFORD: Manchester City’s Argentinian defender Pablo Zabaleta (left) and Manchester United’s English forward Danny Welbeck lie injured after clashing during the English Premier League football match.— AFP Dzeko’s brace give City derby spoils Dzeko claimed his second goal early in the Hertha Berlin to secure the Bundesliga title in invited City to attack them. to deny Dzeko-but they did not heed them second half before Yaya Toure added a late record time. Jones had to slide in to block from Silva after and in the 56th minute it was 2-0. Nasri Man United 0 third to leave Manuel Pellegrini’s side three “We didn’t start the game well,” admitted Carrick lost the ball, while United goalkeeper shaped a corner towards the near post from points behind leaders Chelsea, with two games Moyes.”I think we have played a very good David de Gea produced a superb one-handed the right-hand side and Dzeko left Rio in hand, ahead of Saturday’s trip to Arsenal. side, playing at the sort of level we are aspir- save to thwart Dzeko and atone for a loose kick Ferdinand in his wake to steer a right-foot vol- “We scored three goals and had three or ing to. We need to come up a couple of lev- of his own. ley into the top-right corner. Man City 3 four more good chances to score,” City manager els ourselves because at the moment we are Gradually the hosts began to make inroads, With victory secure, City’s fans delved into Manuel Pellegrini told Sky Sports. -

The Bosman Ruling: Impact of Player Mobility on FIFA Rankings

Haverford College – Economics Department The Bosman Ruling: Impact of Player Mobility on FIFA Rankings Jordana Brownstone 4/29/2010 2 Table of Contents Abstract ...............................................................................................................................3 Acknowledgement ..............................................................................................................4 I. INTRODUCTION ..........................................................................................................5 II. LITERATURE REVIEW ..........................................................................................10 III. DATA AND METHODOLOGY .............................................................................20 Table I .......................................................................................................................22 IV. ESTIMATION ...........................................................................................................23 V. RESULTS ....................................................................................................................23 Table 2 - Effect of Bosman on number of non-Western players in Western European Premier Leagues ........................................................................................................25 Table 3 - Effect of Bosman on regional players in Western Europe ........................27 Table 4 - Effect of Players in “Big 5” Premier Leagues on FIFA rankings ..............28 VI. CONCLUSION ..........................................................................................................31 -

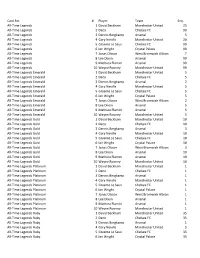

Card Set # Player Team Seq. All-Time Legends 1 David Beckham

Card Set # Player Team Seq. All-Time Legends 1 David Beckham Manchester United 25 All-Time Legends 2 Deco Chelsea FC 99 All-Time Legends 3 Dennis Bergkamp Arsenal 5 All-Time Legends 4 Gary Neville Manchester United 20 All-Time Legends 5 Graeme Le Saux Chelsea FC 99 All-Time Legends 6 Ian Wright Crystal Palace 99 All-Time Legends 7 Jonas Olsson West Bromwich Albion 7 All-Time Legends 8 Lee Dixon Arsenal 99 All-Time Legends 9 Mathieu Flamini Arsenal 99 All-Time Legends 10 Wayne Rooney Manchester United 99 All-Time Legends Emerald 1 David Beckham Manchester United 5 All-Time Legends Emerald 2 Deco Chelsea FC 5 All-Time Legends Emerald 3 Dennis Bergkamp Arsenal 2 All-Time Legends Emerald 4 Gary Neville Manchester United 5 All-Time Legends Emerald 5 Graeme Le Saux Chelsea FC 5 All-Time Legends Emerald 6 Ian Wright Crystal Palace 5 All-Time Legends Emerald 7 Jonas Olsson West Bromwich Albion 2 All-Time Legends Emerald 8 Lee Dixon Arsenal 5 All-Time Legends Emerald 9 Mathieu Flamini Arsenal 5 All-Time Legends Emerald 10 Wayne Rooney Manchester United 5 All-Time Legends Gold 1 David Beckham Manchester United 10 All-Time Legends Gold 2 Deco Chelsea FC 10 All-Time Legends Gold 3 Dennis Bergkamp Arsenal 3 All-Time Legends Gold 4 Gary Neville Manchester United 10 All-Time Legends Gold 5 Graeme Le Saux Chelsea FC 10 All-Time Legends Gold 6 Ian Wright Crystal Palace 10 All-Time Legends Gold 7 Jonas Olsson West Bromwich Albion 3 All-Time Legends Gold 8 Lee Dixon Arsenal 10 All-Time Legends Gold 9 Mathieu Flamini Arsenal 10 All-Time Legends Gold 10 Wayne -

Answer Given by Mr Verheugen on Behalf of the Commission

29.8.2002 EN Official Journal of the European Communities C 205 E/19 Answer given by Mr Verheugen on behalf of the Commission (12 December 2001) Under the European Initiative for Democracy and Human Rights (budget line B7-700), the Commission has provided financial support to the non-governmental organisation (NGO)‘Latvian Human Rights Committee’ for a micro-project entitled ‘Informative Service on Migration Issues’. The total budget of this project was estimated at 4 300 Euro, with a maximum Community funding of 3 850 Euro. The NGO ‘Latvian Human Rights Committee’ aims at defending the interests of the Russian-speaking population in Latvia with a special focus on citizenship issues. The purpose of the project referred to above was to provide information and legal advice on migration legislation in order to reduce the number of persons living in Latvia without any legal status or without any valid personal documents. To achieve this objective, various activities were carried out, including the publication of articles in newspapers that the ‘Latvian Human Rights Committee’ assumed to be read by the target group. One of these was the publication ‘Panorama Latvii’. It should be noted Mr Alfreds Rubiks does not hold any publishing functions in this newspaper, although the newspaper has at some occasions supported his views. The project was carried out in close cooperation with the Department of Citizenship and Migration Affairs of the Latvian Ministry of Interior. (2002/C 205 E/019) WRITTEN QUESTION P-2997/01 by Toine Manders (ELDR) to the Commission (22 October 2001) Subject: Football: undesirable effects of the new transfer system The former transfer system for professional footballers was, as is well known, abolished following the ruling in the Bosman case on the grounds that it contravened the right to freedom of movement within the internal market. -

Hierarchical Clustering

MEF UNIVERSITY FOOTBALL PLAYER PROFILING USING OPTA MATCH EVENT DATA: HIERARCHICAL CLUSTERING Capstone Project Uğurcan Kalenderoğlu İSTANBUL, 2019 ii iii MEF UNIVERSITY FOOTBALL PLAYER PROFILING USING OPTA MATCH EVENT DATA: HIERARCHICAL CLUSTERING Capstone Project Uğurcan Kalenderoğlu Advisor: Asst. Prof. Dr. Utku Koç İSTANBUL, 2019 iv MEF UNIVERSITY Name of the project: Football Player Profiling Using Opta Match Event Data: Hierarchical Clustering Name/Last Name of the Student: Uğurcan Kalenderoğlu Date of Thesis Defense: 09/09/2019 I hereby state that the graduation project prepared by Uğurcan Kalenderoğlu has been completed under my supervision. I accept this work as a “Graduation Project”. 09/09/2019 Asst. Prof. Dr. Utku Koç I hereby state that I have examined this graduation project by Uğurcan Kalenderoğlu which is accepted by his supervisor. This work is acceptable as a graduation project and the student is eligible to take the graduation project examination. 09/09/2019 Prof. Dr. Özgür Özlük Director of Big Data Analytics Program We hereby state that we have held the graduation examination of Uğurcan Kalenderoğlu and agree that the student has satisfied all requirements. THE EXAMINATION COMMITTEE Committee Member Signature 1. Asst. Prof. Dr. Utku Koç ……………………….. 2. Prof. Dr. Özgür Özlük ……………………….. v Academic Honesty Pledge I promise not to collaborate with anyone, not to seek or accept any outside help, and not to give any help to others. I understand that all resources in print or on the web must be explicitly cited. In keeping with MEF University’s ideals, I pledge that this work is my own and that I have neither given nor received inappropriate assistance in preparing it.