University of Cincinnati

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 and 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak a Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate

PERFORMED IDENTITIES: HEAVY METAL MUSICIANS BETWEEN 1984 AND 1991 Bradley C. Klypchak A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate College of Bowling Green State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY May 2007 Committee: Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Dr. John Makay Graduate Faculty Representative Dr. Ron E. Shields Dr. Don McQuarie © 2007 Bradley C. Klypchak All Rights Reserved iii ABSTRACT Dr. Jeffrey A. Brown, Advisor Between 1984 and 1991, heavy metal became one of the most publicly popular and commercially successful rock music subgenres. The focus of this dissertation is to explore the following research questions: How did the subculture of heavy metal music between 1984 and 1991 evolve and what meanings can be derived from this ongoing process? How did the contextual circumstances surrounding heavy metal music during this period impact the performative choices exhibited by artists, and from a position of retrospection, what lasting significance does this particular era of heavy metal merit today? A textual analysis of metal- related materials fostered the development of themes relating to the selective choices made and performances enacted by metal artists. These themes were then considered in terms of gender, sexuality, race, and age constructions as well as the ongoing negotiations of the metal artist within multiple performative realms. Occurring at the juncture of art and commerce, heavy metal music is a purposeful construction. Metal musicians made performative choices for serving particular aims, be it fame, wealth, or art. These same individuals worked within a greater system of influence. Metal bands were the contracted employees of record labels whose own corporate aims needed to be recognized. -

Union Calendar No. 481 104Th Congress, 2D Session – – – – – – – – – – – – House Report 104–879

1 Union Calendar No. 481 104th Congress, 2d Session ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± ± House Report 104±879 REPORT ON THE ACTIVITIES OF THE COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES DURING THE ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS PURSUANT TO CLAUSE 1(d) RULE XI OF THE RULES OF THE HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES JANUARY 2, 1997.ÐCommitted to the Committee of the Whole House on the State of the Union and ordered to be printed U.S. GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 36±501 WASHINGTON : 1997 COMMITTEE ON THE JUDICIARY HOUSE OF REPRESENTATIVES ONE HUNDRED FOURTH CONGRESS HENRY J. HYDE, Illinois, Chairman 1 CARLOS J. MOORHEAD, California JOHN CONYERS, JR., Michigan F. JAMES SENSENBRENNER, JR., PATRICIA SCHROEDER, Colorado Wisconsin BARNEY FRANK, Massachusetts BILL MCCOLLUM, Florida CHARLES E. SCHUMER, New York GEORGE W. GEKAS, Pennsylvania HOWARD L. BERMAN, California HOWARD COBLE, North Carolina RICH BOUCHER, Virginia LAMAR SMITH, Texas JOHN BRYANT, Texas STEVEN SCHIFF, New Mexico JACK REED, Rhode Island ELTON GALLEGLY, California JERROLD NADLER, New York CHARLES T. CANADY, Florida ROBERT C. SCOTT, Virginia BOB INGLIS, South Carolina MELVIN L. WATT, North Carolina BOB GOODLATTE, Virginia XAVIER BECERRA, California STEPHEN E. BUYER, Indiana JOSEÂ E. SERRANO, New York 2 MARTIN R. HOKE, Ohio ZOE LOFGREN, California SONNY BONO, California SHEILA JACKSON LEE, Texas FRED HEINEMAN, North Carolina MAXINE WATERS, California 3 ED BRYANT, Tennessee STEVE CHABOT, Ohio MICHAEL PATRICK FLANAGAN, Illinois BOB BARR, Georgia ALAN F. COFFEY, JR., General Counsel/Staff Director JULIAN EPSTEIN, Minority Staff Director 1 Henry J. Hyde, Illinois, elected to the Committee as Chairman pursuant to House Resolution 11, approved by the House January 5 (legislative day of January 4), 1995. -

Sample Ballot Nov. 2000

SAMPLE BALLOT • GENERAL ELECTION MULTNOMAH COUNTY, OREGON • NOVEMBER 7, 2000 ATTORNEY GENERAL INSTRUCTIONS TO VOTER UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE IN VOTE FOR ONE USE A PENCIL ONLY CONGRESS, 1ST CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT TO VOTE, BLACKEN THE OVAL ( ) VOTE FOR ONE HARDY MYERS Democrat COMPLETELY TO THE LEFT OF THE RESPONSE OF YOUR CHOICE. BETH A. KING KEVIN L. MANNIX Libertarian Republican TO WRITE IN A NAME, BLACKEN THE OVAL ( ) TO THE LEFT OF THE DAVID WU THOMAS B. COX DOTTED LINE AND WRITE THE NAME Democrat Libertarian ON THAT DOTTED LINE. CHARLES STARR _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ Republican NATIONAL STATE SENATOR, 6TH DISTRICT _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ VOTE FOR ONE UNITED STATES PRESIDENT GINNY BURDICK AND VICE PRESIDENT UNITED STATES REPRESENTATIVE IN Democrat Your vote for the candidates for United States CONGRESS, 3RD CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT President and Vice President shall be a vote for VOTE FOR ONE _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ the electors supporting those candidates. VOTE FOR ONE TICKET EARL BLUMENAUER STATE SENATOR, 7TH DISTRICT LIBERTARIAN Democrat VOTE FOR ONE U.S. President, HARRY BROWNE WALTER F. (WALT) BROWN KATE BROWN U.S. Vice President, ART OLIVIER Socialist Democrat BRUCE ALEXANDER KNIGHT CHARLEY J. NIMS INDEPENDENT Libertarian Socialist U.S. President, PATRICK J. BUCHANAN JEFFERY L. POLLOCK _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ _ U.S. -

A History of Maryland's Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016

A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 A History of Maryland’s Electoral College Meetings 1789-2016 Published by: Maryland State Board of Elections Linda H. Lamone, Administrator Project Coordinator: Jared DeMarinis, Director Division of Candidacy and Campaign Finance Published: October 2016 Table of Contents Preface 5 The Electoral College – Introduction 7 Meeting of February 4, 1789 19 Meeting of December 5, 1792 22 Meeting of December 7, 1796 24 Meeting of December 3, 1800 27 Meeting of December 5, 1804 30 Meeting of December 7, 1808 31 Meeting of December 2, 1812 33 Meeting of December 4, 1816 35 Meeting of December 6, 1820 36 Meeting of December 1, 1824 39 Meeting of December 3, 1828 41 Meeting of December 5, 1832 43 Meeting of December 7, 1836 46 Meeting of December 2, 1840 49 Meeting of December 4, 1844 52 Meeting of December 6, 1848 53 Meeting of December 1, 1852 55 Meeting of December 3, 1856 57 Meeting of December 5, 1860 60 Meeting of December 7, 1864 62 Meeting of December 2, 1868 65 Meeting of December 4, 1872 66 Meeting of December 6, 1876 68 Meeting of December 1, 1880 70 Meeting of December 3, 1884 71 Page | 2 Meeting of January 14, 1889 74 Meeting of January 9, 1893 75 Meeting of January 11, 1897 77 Meeting of January 14, 1901 79 Meeting of January 9, 1905 80 Meeting of January 11, 1909 83 Meeting of January 13, 1913 85 Meeting of January 8, 1917 87 Meeting of January 10, 1921 88 Meeting of January 12, 1925 90 Meeting of January 2, 1929 91 Meeting of January 4, 1933 93 Meeting of December 14, 1936 -

November 7, 2000 General Election

i s OFFICIAL COME TOTALS ALL PREC 11-1-00 GEN ELEC 1 10:39:18 20-Nov-2000 perry county °hip general election nay 7th 2000 Total Pct Total Pct Total Pct Precincts Counted - TOTAL 46 100.00 FOR COUNTY COMMISSIONER FOR JUSTICE OF THE SUPREME COURT Precincts Counted - PIKE TAP TOTAL . 9 100.00 FULL TERM COMM 1-3-01 FULL TERM COMM 1-2-01 Precincts Counted - BEARFIELD TAP TOTAL . 2 100.00 JOHN ALTIPR 6,161 50.11 TERRENCE O'DONNELL . 4,618 40.22 Precincts Counted - CLAYTON TAP TOTAL . 2 100.00 MIKE SHERLOCK 6,134 49.89 ALICE ROBIE RESNICK 6,864 59.78 Precincts Counted - COAL TAP TOTAL . 2 100.00 Total 12,295 100.00 Total 11,482 100,00 Precincts Counted - HARRISON TAP TOTAL . 6 100.00 Precincts Counted - HOPEWELL TAP TOTAL . 3 100.00 FOR PROSECUTING ATTORNEY FOR JUDGE OF THE COURT OF APPEALS Precincts Counted - JACKSON TAP TOTAL . 3 100.00 JOSEPH A FLAUTT 6,989 55.79 5TH DIST FULL TERM COMM 2-9-01 Precincts Counted 7 MADISON TAP TOTAL • 1 100.00 ROBERT AARON MILLER 5,539 44.21 JOHN A WISE . 7,504 .19040 Precincts Counted - MONDAY CREEK TOTAL • 1 100.00 Total 12,528 100.00 Total 7,504 100.00 Precincts Counted - MONROE TAP TOTAL . 3 100.00 Precincts Counted - PLEASANT TAP TOTAL 1 100.00 FOR CLERK OF COURT FOR JUDGE OF THE COURT OF APPEALS Precincts Counted - READING TAP TOTAL 5 100.00 OF COMMON PLEAS 5TH DIST FULL TERM COMM 2-10-01 Precincts Counted-- SALTLICK TAP-TOTAL 3 100.00 --- LORI- MARIE ABRAM 997 7.86 A SCOTT GAIN . -

Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008 Robert P

Journal of International Women's Studies Volume 8 | Issue 1 Article 1 Nov-2006 Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008 Robert P. Watson Follow this and additional works at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws Part of the Women's Studies Commons Recommended Citation Watson, Robert P. (2006). Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008. Journal of International Women's Studies, 8(1), 1-20. Available at: http://vc.bridgew.edu/jiws/vol8/iss1/1 This item is available as part of Virtual Commons, the open-access institutional repository of Bridgewater State University, Bridgewater, Massachusetts. This journal and its contents may be used for research, teaching and private study purposes. Any substantial or systematic reproduction, re-distribution, re-selling, loan or sub-licensing, systematic supply or distribution in any form to anyone is expressly forbidden. ©2006 Journal of International Women’s Studies. Madam President: Progress, Problems, and Prospects for 2008 By Robert P. Watson1 Abstract Women have made great progress in electoral politics both in the United States and around the world, and at all levels of public office. However, although a number of women have led their countries in the modern era and a growing number of women are winning gubernatorial, senatorial, and congressional races, the United States has yet to elect a female president, nor has anyone come close. This paper considers the prospects for electing a woman president in 2008 and the challenges facing Hillary Clinton and Condoleezza Rice–potential frontrunners from both major parties–given the historical experiences of women who pursued the nation’s highest office. -

Issues Territoriality Concerning the German Germans Know It! Concerning Imperialism

INSIDE: Maoist game reviews * Under Lock & Key * UnaMIM Notes Página 320 • June en 1-30, Esp 2005a ñol...• Page 1 MIM Notes June 1-30 2005, Nº 320 The Official Newsletter of the Maoist Internationalist Movement (MIM) Free Border vigilantism: fascism, not just race ANDY RAMIREZ Neo-Nazis spoil IS A FASCIST, May 9th VE day NOT JUST A celebrations The collective responsibility ‘COCONUT’ movement By HC116 and [email protected], May 3300 neo-Nazis demonstrated in Berlin 12, 2005 against the celebration of Victory in Friends of the Border Patrol Europe day, the 60th anniversary of the chairpersyn and executive director Andy end of World War II in Europe. A crowd Ramirez was a guest on Monday’s Lou approximately double that size Dobbs Tonight . Ramirez is the former demonstrated to stop them from executive director of the organization Save marching. The Nazi movement in Berlin Our State (Ron Prince), which has is an urgent reminder that MIM’s line for recently opposed legislation in Kalifornia collective responsibility is the only correct to allow undocumented persyns to have road for countries like Germany and the drivers’ licenses, and supported legislation united $tates. in Kalifornia, Proposition 187 (1994), that The neo-Nazis said they should no longer would have prohibited public services, hold the burden for “‘a cult of guilt.’”(1) including health services, for To them, the Soviet invasion of Germany undocumented persyns. Andy Ramirez was not liberation, but “‘occupation’” and has encouraged the u.$. Congress to pass VE celebrations are a product of legislation prohibiting drivers’ licenses for “‘professional Jews.’”(1) It’s the usual undocumented persyns in all States. -

Archive of Newsletters 2000/2001

Archive of Coffee Blossom Newsletters 2000/2001 Contents 2000-07-06 2001-03-01 2000-07-13 2001-03-08 2000-07-20 2001-03-15 2000-07-27 2001-03-22 2000-08-03 2001-03-29 2000-08-10 2001-04-05 2000-08-17 2001-04-12 2000-08-24 2001-04-19 2000-08-31 2001-04-26 2000-09-07 2001-05-03 2000-09-14 2001-05-10 2000-09-21 2001-05-17 2000-09-28 2001-05-24 2000-10-05 2001-05-31 2000-10-12 2001-06-07 2000-10-19 2001-06-14 2000-10-26 2001-06-21 2000-11-02 2001-06-28 2000-11-09 2000-11-16 2000-11-23 2000-11-30 2000-12-07 2000-12-21 2000-12-28 2001-01-11 2001-01-18 2001-01-25 2001-02-01 2001-02-08 2001-02-15 2001-02-22 2000-07-06 1 Royal Kona Resort Officers Installed for 2000-2001 festive luau was a A Jim was our official and entertainment. July 6, 2000 nice way to say thank “lei-person”. Mahalo to Upon the setting of the you to our Past Presi- Jim and Sis for all of sun, dinner was served. dent Gerry Brewster their efforts. After fine dining, and the Board of Direc- Couples were then Past President Gerry tors for 1999-2000 and treated to a photo ses- thanked his outgoing to welcome our new sion with our own Board and President President, Ken Kjer and Charla Thompson. -

Issue 19 Master

WEEKLY NEWSPAPER: DO NOT DELAY—DATE MAILED 12-21-01 HAPPY NEW YEAR! Congress Facilitates Big Brother Brainwashing in Your Public Schools. Pages 8-9. ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ Bin Laden’s Latest Video Tops CIA Propaganda Charts. AmericanFreePressAmericanFreePress Page 3. ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★★For Life & Liberty . Against the New World Order ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ VOLUME I NUMBER 19 DECEMBER 31, 2001 www.americanfreepress.net $1 EACH British Chief of Staff Gun Grabbers Critical of America’s War on Terrorism ‘Stumped’ by Britain’s top military officer warns that the “war on terrorism” will “radical- Pro-Firearms ize” friendly states and lead to increased terrorism. Congressman EXCLUSIVE TO AMERICAN FREE PRESS A pro-gun representative has killed a By Christopher Bollyn controversial addition to legislation which would have meant the destruction hile Secretary of State Colin Powell visited Britain, the United State’s closest ally in of most war-time firearms relics. Afghanistan and only ally in Iraq, on the W three-month anniversary of the Sept. 11 EXCLUSIVE TO AMERICAN FREE PRESS terror, significant differences surfaced on how to proceed By Mike Blair with the “war on terrorism.” British Chief of Staff Admiral Sir Michael Boyce section of the Defense Department budget for revealed a significant divergence between the allies’ mil- 2002, which could have meant the mandated itary and political branches on what to do after the destruction of hundreds of thousands of “war defeat of the Taliban. A relic” firearms, has been killed by a pro-gun Boyce said that America’s determination to use mili- congressman. tary might in a wider war was certain to “radicalize” Through the efforts of Rep. -

2000 General Election Certification

THE COUNTY BOARD OF CANVASSERS The County Board of Canvassers having canvassed the whole number of votes cast for all candidates for the office of PRESIDENT AND VICE-PRESIDENT OF THE UNITED STATES at the General Election held in this state on the 7th day of November, 2000, do hereby certify that the following votes were received: REPUBLICAN George W. Bush and Dick Cheney 131,002 Votes DEMOCRATIC Al Gore and Joe Lieberman 157,314 Votes INDEPENDENCE John Hagelin and Nat Goldhaber 882 Votes CONSERVATIVE George W. Bush and Dick Cheney 10,264 Votes LIBERAL Al Gore and Joe Lieberman 2,884 Votes RIGHT TO LIFE Patrick Buchanan and Ezola Foster 1,308 Votes GREEN Ralph Nader and Winona LaDuke 11,520 Votes WORKING FAMILIES Al Gore and Joe Lieberman 1,545 Votes BUCHANAN REFORM Patrick Buchanan and Ezola Foster 420 Votes SOCIALIST WORKERS James E. Harris and Margaret Trowe 41 Votes LIBERTARIAN Harry Browne and Art Olivier 510 Votes CONSTITUTION Howard Phillips and J. Curtis Frazier 72 Votes Scattering 63 Votes Blank and Void 4,569 Votes Whole number of votes 322,394 Votes The above total includes 98 Special Presidential Ballots and 306 Special Federal Ballots. 1 THE COUNTY BOARD OF CANVASSERS The County Board of Canvassers having canvassed the whole number of votes cast for all candidates for the office of UNITED STATES SENATOR at the General Election held in this state on the 7th day of November, 2000, do hereby certify that the following votes were received: REPUBLICAN Rick Lazio 145,285 Votes DEMOCRATIC Hillary Rodham Clinton 147,329 Votes INDEPENDENCE Jeffrey E. -

A.S. Fights Students' Deportation

SERVING SAN JOSE STATE UNIVERSITY SINCE 1934 SPARTANSPARTAN DAILYDAILY WWW.THESPARTANDAILY.COM VOLUME 122, NUMBER 09 THURSDAY, FEBRUARY 12, 2004 “The Rock & Roll Barber” A.S. fi ghts students’ deportation Board also hears plea for Bay Area man jailed by Chinese government Dafa Association at SJSU, spoke to the By John Myers board along with the accompaniment of Daily Staff Writer Yeong-Ching Foo, the fi ancee of Charles Li, an American citizen and former The San Jose State University As- Menlo Park resident who is currently sociated Students government addressed incarcerated in China. more than everyday events during its According to Lam, Li was arrested meeting Wednesday. and prosecuted for practicing Falun The governing body also considered Dafa, a meditation technique also known political problems that affect more as Falun Gong. Li was sentenced on than just the students on campus, such March 21, 2003, to three years in prison as a family’s possible deportation and in China, according to Friends of Falun an American citizen’s incarceration in Gong, an American nonprofi t organiza- China. tion that supports the freedom of people Director of Governing Affairs Huy who practice Falun Gong. Tran proposed Resolution 03/04-08 to “Falun Gong is persecuted in voice the Associated Students’ opposi- China,” Lam said. “Communist China tion to the deportation of the Cuevas feared a rapid growth (of Falun Gong family, including Dale and Dominique practitioners).” Cuevas who both attend SJSU, accord- Foo explained ing to the meeting’s the success she has Photos by Susan D. Reno / Daily Staff agenda. -

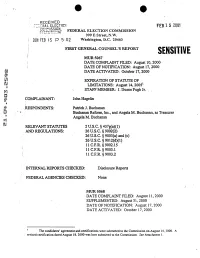

SENSITIVE MUR 5067 I DATE COMPLAINT FLED: August 10,2000 DATE of NOTIFICATION: August 17,2000 DATE ACTIVATED: October 17,2000

" . FEDERAL ELECTION CO'MMISSION 999 E Street, N.W. ZOO! FE8 I5 P S: 02 Washington, D.C. 20463 I I FIRST GENERAL COUNSEL'S REPORT SENSITIVE MUR 5067 I DATE COMPLAINT FLED: August 10,2000 DATE OF NOTIFICATION: August 17,2000 DATE ACTIVATED: October 17,2000 EXPlRATION OF STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS: August 14,2005' STAFF MEMBER: J. Duane Pugh Jr. COhmLAINANT: John Hagelin I RESPONDENTS: Patrick J. Buchanan Buchanan Reform, Inc., and Angela M. Buchanan, as Treasurer w Angela M. Buchanan RELEVANT STATUTES 2 U.S.C. 5 437g(a)(l) AND REGULATIONS: 26 U.S.C. 5 9002(2) 26 U.S.C. 5 9003(a) and (c) 26 U.S.C.5 9012(d)(l) 11 C.F.R. 0 9002.15 . 11 C.F.R. 5 9003.1 11 C.F.R. 5 9003.2 INTERNAL REPORTS CHECKED: Disclosure Reports FEDERAL AGENCIES CHECKED: None MUR 5068 DATE COMPLAINT FLED: August 11,2000 SUPPLEMENTED: August 3 1,2000 DATE OF NOTIFICATION: 'August 17,2000 DATE ACTIVATED: October 17,2000 ~ ~ ~~ I The candidates' agreement and certifications were submitted to the Commission on August 14, 2000. A revised certification dated August 18,2000 was later submined to the Commission. See Attachment 1. MURs 5067,5068 and 5081: 2 . First General Counsel's Report' EXPIRATION OF STATUTE OF LIMITATIONS: August 14,2005 STAFF MEMBER: . J. Duane Pugh Jr. .. COMPLAINANT: James Mangia RESPONDENTS: Patrick J. Buchanan Buchanan Reform, Inc., and Angela M. Buchanan, as Treasurer Angela M. Buchanan Gerald M. Moan 2 U.S.C. 5 437g(a)(l) 26 U.S.C.5 9002(2) 26 U.S.C.