From Genetics to Genomics of Epilepsy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Analysis of Gene–Environment Interactions in Postnatal

– Analysis of gene environment interactions in postnatal INAUGURAL ARTICLE development of the mammalian intestine Seth Rakoff-Nahouma,b,c,1, Yong Kongd, Steven H. Kleinsteine, Sathish Subramanianf, Philip P. Ahernf, Jeffrey I. Gordonf, and Ruslan Medzhitova,b,1 aHoward Hughes Medical Institute, bDepartment of Immunobiology, dDepartment of Molecular Biophysics and Biochemistry, W. M. Keck Foundation Biotechnology Resource Laboratory, and eInterdepartmental Program in Computational Biology and Bioinformatics and Department of Pathology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT 06510; fCenter for Genome Sciences and Systems Biology, Washington University School of Medicine in St. Louis, St. Louis, MO 63108; and cDivision of Infectious Diseases, Department of Medicine, Boston Children’s Hospital and Harvard Medical School, Boston, MA 02115 This contribution is part of the special series of Inaugural Articles by members of the National Academy of Sciences elected in 2010. Contributed by Ruslan Medzhitov, December 31, 2014 (sent for review December 25, 2014; reviewed by Alexander V. Chervonsky and Alexander Y. Rudensky) Unlike mammalian embryogenesis, which takes place in the relatively immediately after birth, the intestine is exposed to mother’s milk predictable and stable environment of the uterus, postnatal develop- and undergoes initial colonization with microorganisms. Second, ment can be affected by a multitude of highly variable environmental after weaning, the intestinal tract becomes exposed to solid foods factors, including diet, exposure to noxious substances, and micro- and is no longer exposed to mother’s milk components, the host organisms. Microbial colonization of the intestine is thought to play a immune system matures, and the microbiota shifts. particularly important role in postnatal development of the gastroin- Although it is widely recognized that these transitions have testinal, metabolic, and immune systems. -

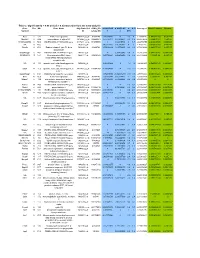

Supplement 1 Overview of Dystonia Genes

Supplement 1 Overview of genes that may cause dystonia in children and adolescents Gene (OMIM) Disease name/phenotype Mode of inheritance 1: (Formerly called) Primary dystonias (DYTs): TOR1A (605204) DYT1: Early-onset generalized AD primary torsion dystonia (PTD) TUBB4A (602662) DYT4: Whispering dystonia AD GCH1 (600225) DYT5: GTP-cyclohydrolase 1 AD deficiency THAP1 (609520) DYT6: Adolescent onset torsion AD dystonia, mixed type PNKD/MR1 (609023) DYT8: Paroxysmal non- AD kinesigenic dyskinesia SLC2A1 (138140) DYT9/18: Paroxysmal choreoathetosis with episodic AD ataxia and spasticity/GLUT1 deficiency syndrome-1 PRRT2 (614386) DYT10: Paroxysmal kinesigenic AD dyskinesia SGCE (604149) DYT11: Myoclonus-dystonia AD ATP1A3 (182350) DYT12: Rapid-onset dystonia AD parkinsonism PRKRA (603424) DYT16: Young-onset dystonia AR parkinsonism ANO3 (610110) DYT24: Primary focal dystonia AD GNAL (139312) DYT25: Primary torsion dystonia AD 2: Inborn errors of metabolism: GCDH (608801) Glutaric aciduria type 1 AR PCCA (232000) Propionic aciduria AR PCCB (232050) Propionic aciduria AR MUT (609058) Methylmalonic aciduria AR MMAA (607481) Cobalamin A deficiency AR MMAB (607568) Cobalamin B deficiency AR MMACHC (609831) Cobalamin C deficiency AR C2orf25 (611935) Cobalamin D deficiency AR MTRR (602568) Cobalamin E deficiency AR LMBRD1 (612625) Cobalamin F deficiency AR MTR (156570) Cobalamin G deficiency AR CBS (613381) Homocysteinuria AR PCBD (126090) Hyperphelaninemia variant D AR TH (191290) Tyrosine hydroxylase deficiency AR SPR (182125) Sepiaterine reductase -

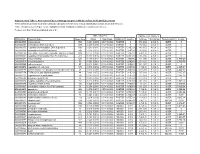

Table 2. Significant

Table 2. Significant (Q < 0.05 and |d | > 0.5) transcripts from the meta-analysis Gene Chr Mb Gene Name Affy ProbeSet cDNA_IDs d HAP/LAP d HAP/LAP d d IS Average d Ztest P values Q-value Symbol ID (study #5) 1 2 STS B2m 2 122 beta-2 microglobulin 1452428_a_at AI848245 1.75334941 4 3.2 4 3.2316485 1.07398E-09 5.69E-08 Man2b1 8 84.4 mannosidase 2, alpha B1 1416340_a_at H4049B01 3.75722111 3.87309653 2.1 1.6 2.84852656 5.32443E-07 1.58E-05 1110032A03Rik 9 50.9 RIKEN cDNA 1110032A03 gene 1417211_a_at H4035E05 4 1.66015788 4 1.7 2.82772795 2.94266E-05 0.000527 NA 9 48.5 --- 1456111_at 3.43701477 1.85785922 4 2 2.8237185 9.97969E-08 3.48E-06 Scn4b 9 45.3 Sodium channel, type IV, beta 1434008_at AI844796 3.79536664 1.63774235 3.3 2.3 2.75319499 1.48057E-08 6.21E-07 polypeptide Gadd45gip1 8 84.1 RIKEN cDNA 2310040G17 gene 1417619_at 4 3.38875643 1.4 2 2.69163229 8.84279E-06 0.0001904 BC056474 15 12.1 Mus musculus cDNA clone 1424117_at H3030A06 3.95752801 2.42838452 1.9 2.2 2.62132809 1.3344E-08 5.66E-07 MGC:67360 IMAGE:6823629, complete cds NA 4 153 guanine nucleotide binding protein, 1454696_at -3.46081884 -4 -1.3 -1.6 -2.6026947 8.58458E-05 0.0012617 beta 1 Gnb1 4 153 guanine nucleotide binding protein, 1417432_a_at H3094D02 -3.13334396 -4 -1.6 -1.7 -2.5946297 1.04542E-05 0.0002202 beta 1 Gadd45gip1 8 84.1 RAD23a homolog (S. -

Assessment of a Targeted Gene Panel for Identification of Genes Associated with Movement Disorders

Supplementary Online Content Montaut S, Tranchant C, Drouot N, et al; French Parkinson’s and Movement Disorders Consortium. Assessment of a targeted gene panel for identification of genes associated with movement disorders. JAMA Neurol. Published online June 18, 2018. doi:10.1001/jamaneurol.2018.1478 eMethods. Supplemental methods. eTable 1. Name, phenotype and inheritance of the genes included in the panel. eTable 2. Probable pathogenic variants identified in a cohort of 23 patients with cerebellar ataxia using WES analysis. eTable 3. Negative cases in a cohort of 23 patients with cerebellar ataxia studied using WES analysis. eTable 4. Variants of unknown significance (VUSs) identified in the cohort. eFigure 1. Examples of pedigrees of cases with identified causative variants. eFigure 2. Pedigrees suggesting mendelian inheritance in negative cases. eFigure 3. Examples of pedigrees of cases with identified VUSs. eResults. Supplemental results. This supplementary material has been provided by the authors to give readers additional information about their work. © 2018 American Medical Association. All rights reserved. Downloaded From: https://jamanetwork.com/ on 09/26/2021 eMethods. Supplemental methods Patients selection In the multicentric, prospective study, patients were selected from 25 French, 1 Luxembourg and 1 Algerian tertiary MDs centers between September 2014 and July 2016. Inclusion criteria were patients (1) who had developed one or several chronic MDs (2) with an age of onset below 40 years and/or presence of a family history of MDs. Patients suffering from essential tremor, tic or Gilles de la Tourette syndrome, pure cerebellar ataxia or with clinical/paraclinical findings suggestive of an acquired cause were excluded. -

A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of Β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus

Page 1 of 781 Diabetes A Computational Approach for Defining a Signature of β-Cell Golgi Stress in Diabetes Mellitus Robert N. Bone1,6,7, Olufunmilola Oyebamiji2, Sayali Talware2, Sharmila Selvaraj2, Preethi Krishnan3,6, Farooq Syed1,6,7, Huanmei Wu2, Carmella Evans-Molina 1,3,4,5,6,7,8* Departments of 1Pediatrics, 3Medicine, 4Anatomy, Cell Biology & Physiology, 5Biochemistry & Molecular Biology, the 6Center for Diabetes & Metabolic Diseases, and the 7Herman B. Wells Center for Pediatric Research, Indiana University School of Medicine, Indianapolis, IN 46202; 2Department of BioHealth Informatics, Indiana University-Purdue University Indianapolis, Indianapolis, IN, 46202; 8Roudebush VA Medical Center, Indianapolis, IN 46202. *Corresponding Author(s): Carmella Evans-Molina, MD, PhD ([email protected]) Indiana University School of Medicine, 635 Barnhill Drive, MS 2031A, Indianapolis, IN 46202, Telephone: (317) 274-4145, Fax (317) 274-4107 Running Title: Golgi Stress Response in Diabetes Word Count: 4358 Number of Figures: 6 Keywords: Golgi apparatus stress, Islets, β cell, Type 1 diabetes, Type 2 diabetes 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online August 20, 2020 Diabetes Page 2 of 781 ABSTRACT The Golgi apparatus (GA) is an important site of insulin processing and granule maturation, but whether GA organelle dysfunction and GA stress are present in the diabetic β-cell has not been tested. We utilized an informatics-based approach to develop a transcriptional signature of β-cell GA stress using existing RNA sequencing and microarray datasets generated using human islets from donors with diabetes and islets where type 1(T1D) and type 2 diabetes (T2D) had been modeled ex vivo. To narrow our results to GA-specific genes, we applied a filter set of 1,030 genes accepted as GA associated. -

1 Metabolic Dysfunction Is Restricted to the Sciatic Nerve in Experimental

Page 1 of 255 Diabetes Metabolic dysfunction is restricted to the sciatic nerve in experimental diabetic neuropathy Oliver J. Freeman1,2, Richard D. Unwin2,3, Andrew W. Dowsey2,3, Paul Begley2,3, Sumia Ali1, Katherine A. Hollywood2,3, Nitin Rustogi2,3, Rasmus S. Petersen1, Warwick B. Dunn2,3†, Garth J.S. Cooper2,3,4,5* & Natalie J. Gardiner1* 1 Faculty of Life Sciences, University of Manchester, UK 2 Centre for Advanced Discovery and Experimental Therapeutics (CADET), Central Manchester University Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester Academic Health Sciences Centre, Manchester, UK 3 Centre for Endocrinology and Diabetes, Institute of Human Development, Faculty of Medical and Human Sciences, University of Manchester, UK 4 School of Biological Sciences, University of Auckland, New Zealand 5 Department of Pharmacology, Medical Sciences Division, University of Oxford, UK † Present address: School of Biosciences, University of Birmingham, UK *Joint corresponding authors: Natalie J. Gardiner and Garth J.S. Cooper Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Address: University of Manchester, AV Hill Building, Oxford Road, Manchester, M13 9PT, United Kingdom Telephone: +44 161 275 5768; +44 161 701 0240 Word count: 4,490 Number of tables: 1, Number of figures: 6 Running title: Metabolic dysfunction in diabetic neuropathy 1 Diabetes Publish Ahead of Print, published online October 15, 2015 Diabetes Page 2 of 255 Abstract High glucose levels in the peripheral nervous system (PNS) have been implicated in the pathogenesis of diabetic neuropathy (DN). However our understanding of the molecular mechanisms which cause the marked distal pathology is incomplete. Here we performed a comprehensive, system-wide analysis of the PNS of a rodent model of DN. -

Supplementary Materials

1 Supplementary Materials: Supplemental Figure 1. Gene expression profiles of kidneys in the Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice. (A) A heat map of microarray data show the genes that significantly changed up to 2 fold compared between Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice (N=4 mice per group; p<0.05). Data show in log2 (sample/wild-type). 2 Supplemental Figure 2. Sting signaling is essential for immuno-phenotypes of the Fcgr2b-/-lupus mice. (A-C) Flow cytometry analysis of splenocytes isolated from wild-type, Fcgr2b-/- and Fcgr2b-/-. Stinggt/gt mice at the age of 6-7 months (N= 13-14 per group). Data shown in the percentage of (A) CD4+ ICOS+ cells, (B) B220+ I-Ab+ cells and (C) CD138+ cells. Data show as mean ± SEM (*p < 0.05, **p<0.01 and ***p<0.001). 3 Supplemental Figure 3. Phenotypes of Sting activated dendritic cells. (A) Representative of western blot analysis from immunoprecipitation with Sting of Fcgr2b-/- mice (N= 4). The band was shown in STING protein of activated BMDC with DMXAA at 0, 3 and 6 hr. and phosphorylation of STING at Ser357. (B) Mass spectra of phosphorylation of STING at Ser357 of activated BMDC from Fcgr2b-/- mice after stimulated with DMXAA for 3 hour and followed by immunoprecipitation with STING. (C) Sting-activated BMDC were co-cultured with LYN inhibitor PP2 and analyzed by flow cytometry, which showed the mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of IAb expressing DC (N = 3 mice per group). 4 Supplemental Table 1. Lists of up and down of regulated proteins Accession No. -

Peripheral Neuropathy in Complex Inherited Diseases: an Approach To

PERIPHERAL NEUROPATHY IN COMPLEX INHERITED DISEASES: AN APPROACH TO DIAGNOSIS Rossor AM1*, Carr AS1*, Devine H1, Chandrashekar H2, Pelayo-Negro AL1, Pareyson D3, Shy ME4, Scherer SS5, Reilly MM1. 1. MRC Centre for Neuromuscular Diseases, UCL Institute of Neurology and National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London, WC1N 3BG, UK. 2. Lysholm Department of Neuroradiology, National Hospital for Neurology and Neurosurgery, London, WC1N 3BG, UK. 3. Unit of Neurological Rare Diseases of Adulthood, Carlo Besta Neurological Institute IRCCS Foundation, Milan, Italy. 4. Department of Neurology, University of Iowa, 200 Hawkins Drive, Iowa City, IA 52242, USA 5. Department of Neurology, University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA 19014, USA. * These authors contributed equally to this work Corresponding author: Mary M Reilly Address: MRC Centre for Neuromuscular Diseases, 8-11 Queen Square, London, WC1N 3BG, UK. Email: [email protected] Telephone: 0044 (0) 203 456 7890 Word count: 4825 ABSTRACT Peripheral neuropathy is a common finding in patients with complex inherited neurological diseases and may be subclinical or a major component of the phenotype. This review aims to provide a clinical approach to the diagnosis of this complex group of patients by addressing key questions including the predominant neurological syndrome associated with the neuropathy e.g. spasticity, the type of neuropathy, and the other neurological and non- neurological features of the syndrome. Priority is given to the diagnosis of treatable conditions. Using this approach, we associated neuropathy with one of three major syndromic categories - 1) ataxia, 2) spasticity, and 3) global neurodevelopmental impairment. Syndromes that do not fall easily into one of these three categories can be grouped according to the predominant system involved in addition to the neuropathy e.g. -

4-6 Weeks Old Female C57BL/6 Mice Obtained from Jackson Labs Were Used for Cell Isolation

Methods Mice: 4-6 weeks old female C57BL/6 mice obtained from Jackson labs were used for cell isolation. Female Foxp3-IRES-GFP reporter mice (1), backcrossed to B6/C57 background for 10 generations, were used for the isolation of naïve CD4 and naïve CD8 cells for the RNAseq experiments. The mice were housed in pathogen-free animal facility in the La Jolla Institute for Allergy and Immunology and were used according to protocols approved by the Institutional Animal Care and use Committee. Preparation of cells: Subsets of thymocytes were isolated by cell sorting as previously described (2), after cell surface staining using CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD3ε (145- 2C11), CD24 (M1/69) (all from Biolegend). DP cells: CD4+CD8 int/hi; CD4 SP cells: CD4CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo; CD8 SP cells: CD8 int/hi CD4 CD3 hi, CD24 int/lo (Fig S2). Peripheral subsets were isolated after pooling spleen and lymph nodes. T cells were enriched by negative isolation using Dynabeads (Dynabeads untouched mouse T cells, 11413D, Invitrogen). After surface staining for CD4 (GK1.5), CD8 (53-6.7), CD62L (MEL-14), CD25 (PC61) and CD44 (IM7), naïve CD4+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo and naïve CD8+CD62L hiCD25-CD44lo were obtained by sorting (BD FACS Aria). Additionally, for the RNAseq experiments, CD4 and CD8 naïve cells were isolated by sorting T cells from the Foxp3- IRES-GFP mice: CD4+CD62LhiCD25–CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– and CD8+CD62LhiCD25– CD44lo GFP(FOXP3)– (antibodies were from Biolegend). In some cases, naïve CD4 cells were cultured in vitro under Th1 or Th2 polarizing conditions (3, 4). -

Supplemental Table 10

Supplemental Table 10: Dietary Impact on the Heart Sulfhydrome DR/AL Accession Alternate Molecular Cysteine Spectral Protein Name Number ID Weight Residues Count Ratio P‐value Ig lambda‐2 chain C region P01844 Iglc2 11 kDa 3 C 16.000 0.00101 Gelsolin P13020 (+1) Gsn 86 kDa 7 C 11.130 0.00133 Glutamate‐‐cysteine ligase regulatory subunit O09172 Gclm 31 kDa 6 C 10.200 0.0307 Ig gamma‐3 chain C region P03987 44 kDa 10 C 7.636 0.0005 Ferritin heavy chain P09528 Fth1 21 kDa 3 C 6.182 0.02617 Antithrombin‐III P32261 Serpinc1 52 kDa 9 C 5.333 0.03116 Bisphosphoglycerate mutase P15327 Bpgm 30 kDa 3 C 4.645 0.01998 Vitamin D‐binding protein Q9QVP4 Gc 54 kDa 28 C 4.541 0.0206 Properdin P11680 Cfp 50 kDa 44 C 3.692 0.0227 Complement factor B P01867 (+1) Cfb 85 kDa 20 C 3.636 0.01126 Transforming growth factor beta‐1 P04202 Tgfb1 44 kDa 12 C 3.273 0.00601 Ferritin light chain 1 P29391 Ftl1 21 kDa 1 C 3.250 0.0204 Ig lambda‐1 chain C region Q9CPV4‐2 12 kDa 3 C 2.844 0.02618 Kininogen‐1 Q8K182 Kng1 73 kDa 19 C 2.840 0.01359 Beta‐2‐glycoprotein 1 Q01339 Apoh 39 kDa 23 C 2.691 0.00579 Complement C3 P01027 C3 186 kDa 27 C 2.556 0.00991 Complement factor I P02088 Cfi 67 kDa 40 C 2.324 0.02636 Ig heavy chain V region 102 P01750 13 kDa 3 C 16.200 0.1642 Afamin O89020 (+1) Afm 69 kDa 34 C 14.400 0.07963 Dehydrogenase/reductase SDR family member 11 Q3U0B3 Dhrs11 28 kDa 8 C 10.400 0.09207 Myosin light chain 4 P09541 Myl4 21 kDa 2 C 9.908 0.23919 Myeloperoxidase P11247 Mpo 81 kDa 16 C 8.800 0.40708 Myosin regulatory light chain 2, skeletal muscle isoform P97457 -

Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for Hepg2 Experiments These Tables Show Details for All Gene Ontology Categories

Supplementary Table 1: Association of Gene Ontology Categories with Decay Rate for HepG2 Experiments These tables show details for all Gene Ontology categories. Inferences for manual classification scheme shown at the bottom. Those categories used in Figure 1A are highlighted in bold. Standard Deviations are shown in parentheses. P-values less than 1E-20 are indicated with a "0". Rate r (hour^-1) Half-life < 2hr. Decay % GO Number Category Name Probe Sets Group Non-Group Distribution p-value In-Group Non-Group Representation p-value GO:0006350 transcription 1523 0.221 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.1 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006351 transcription, DNA-dependent 1498 0.220 (0.009) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 0 13.0 (0.4) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006355 regulation of transcription, DNA-dependent 1163 0.230 (0.011) 0.128 (0.002) FASTER 5.00E-21 14.2 (0.5) 4.6 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006366 transcription from Pol II promoter 845 0.225 (0.012) 0.130 (0.002) FASTER 1.88E-14 13.0 (0.5) 4.8 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006139 nucleobase, nucleoside, nucleotide and nucleic acid metabolism3004 0.173 (0.006) 0.127 (0.002) FASTER 1.28E-12 8.4 (0.2) 4.5 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0006357 regulation of transcription from Pol II promoter 487 0.231 (0.016) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 6.05E-10 13.5 (0.6) 4.9 (0.1) OVER 0 GO:0008283 cell proliferation 625 0.189 (0.014) 0.132 (0.002) FASTER 1.95E-05 10.1 (0.6) 5.0 (0.1) OVER 1.50E-20 GO:0006513 monoubiquitination 36 0.305 (0.049) 0.134 (0.002) FASTER 2.69E-04 25.4 (4.4) 5.1 (0.1) OVER 2.04E-06 GO:0007050 cell cycle arrest 57 0.311 (0.054) 0.133 (0.002) -

Trypanosoma Brucei Ribonuclease H2A Is an Essential Enzyme That Resolves R-Loops Associated with Transcription Initiation and Antigenic Variation

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/541300; this version posted February 5, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. Trypanosoma brucei ribonuclease H2A is an essential enzyme that resolves R-loops associated with transcription initiation and antigenic variation Emma Briggs1, Kathryn Crouch1, Leandro Lemgruber1, Graham Hamilton2, Craig Lapsley1 and Richard McCulloch1 1. The Wellcome Centre for Molecular Parasitology, University of Glasgow, College of Medical, Veterinary and Life Sciences, Institute of Infection, Immunity and Inflammation, Sir Graeme Davies Building, 120 University Place, Glasgow, G12 8TA, U.K. 2. Glasgow Polyomics, University of Glasgow, Wolfson Wohl Cancer Res Centre, Garscube Estate, Switchback Rd, Bearsden, G61 1QH, U.K. *Correspondence: [email protected] 1 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/541300; this version posted February 5, 2019. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder, who has granted bioRxiv a license to display the preprint in perpetuity. It is made available under aCC-BY 4.0 International license. In every cell ribonucleotides represent a threat to the stability and transmission of the DNA genome. Two types of Ribonuclease H (RNase H) tackle such ribonucleotides, either by excision when they form part of the DNA strand, or by hydrolysing RNA when it base-pairs with DNA, in structures termed R-loops. Loss of either RNase H is lethal in mammals, whereas yeast can prosper in the absence of both enzymes.