Barriers to Understanding the Influence of Use of Fire by Aborigines on Vegetation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Rifle Hunting

TABLE OF CONTENTS Hunting and Outdoor Skills Member Manual ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A. Introduction to Hunting 1. History of Hunting 5 2. Why We Hunt 10 3. Hunting Ethics 12 4. Hunting Laws and Regulations 20 5. Hunter and Landowner Relations 22 6. Wildlife Management and the Hunter 28 7. Careers in Hunting, Shooting Sports and Wildlife Management 35 B. Types of Hunting 1. Hunting with a Rifle 40 2. Hunting with a Shotgun 44 3. Hunting with a Handgun 48 4. Hunting with a Muzzleloading 51 5. Bowhunting 59 6. Hunting with a Camera 67 C. Outdoor and Hunting Equipment 1. Use of Map and Compass 78 2. Using a GPS 83 3. Choosing and Using Binoculars 88 4. Hunting Clothing 92 5. Cutting Tools 99 D. Getting Ready for the Hunt 1. Planning the Hunt 107 2. The Hunting Camp 109 3. Firearm Safety for the Hunter 118 4. Survival in the Outdoors 124 E. Hunting Skills and Techniques 1. Recovering Game 131 2. Field Care and Processing of Game 138 3. Hunting from Stands and Blinds 144 4. Stalking Game Animals 150 5. Hunting with Dogs 154 F. Popular Game Species 1. Hunting Rabbits and Hares 158 2. Hunting Squirrels 164 3. Hunting White-tailed Deer 171 4. Hunting Ring-necked Pheasants 179 5. Hunting Waterfowl 187 6. Hunting Wild Turkeys 193 2 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The 4-H Shooting Sports Hunting Materials were first put together about 25 years ago. Since that time there have been periodic updates and additions. Some of the authors are known, some are unknown. Some did a great deal of work; some just shared morsels of their expertise. -

SSAA Guidelines for the Use of Black Powder

SSAA GUIDELINES FOR THE USE OF BLACK POWDER 2012 No. 1 2 GUIDELINES FOR THE USE OF BLACK POWDER ON SSAA RANGES 1. BLACK POWDER 1.1. Only commercially made Black Powder or Black Powder substitute is to be used. 1.2. When Black Powder events are being held smoking or naked flames are not permitted within 10 metres of the firing line or the designated safe area for open bulk container and to comply with legislation. 1.3. A designated safe area will be allocated at each match for measuring out powder charges and loading cartridges, such an area shall be a minimum of 10 metres from the firing line and to comply with legislation. 1.4. Supplies of bulk powder are to be kept in designated areas at least 20m from any open flame. 1.5. Powder should be stored in its original container. 1.6. Powder in bulk is not allowed on the firing line. 1.7. All Black Powder on the firing line must be held as pre-measured loads in separate containers. 1.8. Only enough black powder for immediate reasonable use may be brought to the firing point. 1.9. No firearms may be loaded directly from a bulk Black Powder container. This includes the use of powder flasks or powder horns. 1.10. Powder may not be measured into loads from bulk containers on the firing line. 1.11. All spilt black powder must be immediately, safely and properly disposed of. 1.12. Powder shall not be placed in direct sunlight. 1.13. -

Download Attachment

Planetarium Science Center newsletterth st 6 year | 1 edition Science For All! 1st SCHOOL SEMESTER 2012/13 In this edition... The Origins of the Four Elements 2 Four Elements: The Powers of the Four Elements 4 The Fifth Element on the Big Screen 5 By: Maissa Azab Journey to the Moon 6 Roots of Life Plasma: The Uncharted Element 7 The Four Elements; the Epitome of Life 8 The Elements’ Wrath 11 Here we start a new year for the PSC and how they can devastate life just as much as The Four Elements that Make Your Body 14 Newsletter; the fourth for the Newsletter as a they sustain it. Nano-Elements of Nature 16 popular science publication. In what has become In this new cycle, we re-introduce sections Lessons from the Lorax 17 a tradition, in the first issue of every new cycle, such as “ZoomTech”, where we discuss how Antimatter: Mirror of the Universe 18 we go back to the roots. Last year, we started by nanotechnology can change the four elements as we know them. In this issue, we also introduce The Marvels of the Elements 20 discussing Planet Earth; this year, we focus in this new sections and columns. In the newly-introduced Fire Breathing Dragons 22 issue on the classical Four Elements of Nature, which were the core of all humanities and sciences “Science in Sci-Fi” section, we have a column on for centuries, if not millennia of human history. the fantastical action motion picture “The Fifth Element”, and a fascinating film review on the Earth, Water, Air, and Fire are indeed the four surprisingly insightful animation movie “The Lorax”. -

STANDARDS for HISTORIC WEAPONS USE Revised September 2018

MARYLAND PARK SERVICE STANDARDS FOR HISTORIC WEAPONS USE Revised September 2018 Maryland Park Service Revised, September 2018 Standards for Historic Weapons Use MARYLAND PARK SERVICE STANDARDS FOR HISTORIC WEAPONS USE Revised September 2018 Table of Contents Purpose ..................................................................................................................................................... 3 Definitions................................................................................................................................................ 3 Rules and Roles for the Historic Weapons Safety Committee, Instructors and Officers ......................... 4 Universal Standards for All Historic Weapons Demonstrations .............................................................. 5 Rules for Non-Firing Demonstrations ...................................................................................................... 7 Rules for Edged Weapons and Tools ....................................................................................................... 7 Rules for Small Arms Demonstrations (Infantry and Cavalry) ............................................................... 8 Rules for Artillery Demonstrations ........................................................................................................ 10 Appendix A: Range for Small Arms Blank Firing................................................................................. 14 Appendix B: Range for Blank Cannon Firing ...................................................................................... -

Explosives Section 433:00. Scope of Section 433. Subd. 1. Sections 433:00 Et Seq. Will Apply to the Manufacture

Section 433 - Explosives Section 433:00. Scope of Section 433. Subd. 1. Sections 433:00 et seq. will apply to the manufacture, possession, storage, sale, transportation, and use of explosives and blasting agents. Subd. 2. Sections 433:00 et seq. will not apply to the following: (a) Transportation of explosives or blasting agents when under the jurisdiction of and in compliance with the regulations of the Federal Department of Transportation. (b) Shipment, transportation and handling of military explosives by the Armed Forces of the United States and the State military forces. (c) Transportation and use of explosives or blasting agents in the normal and emergency operation of federal agencies or state or municipal fire and police departments, providing they are acting in their official capacities and in the proper performance of their duties. (d) Sale, use or public display of pyrotechnics commonly known as fireworks. Subd. 3. Sections 433:00 et seq. will not apply to the following commodities and items: (a) Stocks of small arms ammunition; propellant-actuated power cartridges; small arms ammunition primers in quantities of less than 1,000,000 smokeless propellant in quantities of less than 750 pounds. (b) Explosive actuated power devices when in quantities of less than 50 pounds net weight of explosives. (c) Fuse lighters and fuse igniters. (d) Safety fuse (safety fuse does not include cordeau detonant fuse), and 3/32 inch cannon fuses or matchlock fuses (slow match). (e) The sale or transfer of black powder or other commonly used non-smokeless propellant in individual transactions involving quantities of five (5) pounds or less when used for muzzle loaded firearms or used in the handloading of firearms Section 433:05. -

A Guide to Hunting Responsibly and Safely

For Instructor Use Only TODAY’S HUNTER® a guide to hunting responsibly and safely Copyright © 2012 Kalkomey Enterprises, Inc., www.kalkomey.com For Instructor Use Only THE TEN COMMANDMENTS OF FIREARM SAFETY 1. Watch that muzzle! Keep it pointed in a safe direction at all times. 2. Treat every firearm with the respect due a loaded gun. It might be, even if you think it isn’t. 3. Be sure of the target and what is in front of it and beyond it. Know the identifying features of the game you hunt. Make sure you have an adequate backstop— don’t shoot at a flat, hard surface or water. 4. Keep your finger outside the trigger guard until ready to shoot. This is the best way to prevent an acci- dental discharge. 5. Check your barrel and ammunition. Make sure the barrel and action are clear of obstructions, and carry only the proper ammunition for your firearm. 6. Unload firearms when not in use. Leave actions open, and carry firearms in cases and unloaded to and from the shooting area. 7. Point a firearm only at something you intend to shoot. Avoid all horseplay with a gun. 8. Don’t run, jump, or climb with a loaded firearm. Unload a firearm before you climb a fence or tree, or jump a ditch. Pull a firearm toward you by the butt, not the muzzle. 9. Store firearms and ammunition separately and safely. Store each in secured locations beyond the reach of children and careless adults. 10. Avoid alcoholic beverages before and during shooting. -

The Death of the Knight

Academic Forum 21 2003-04 The Death of the Knight: Changes in Military Weaponry during the Tudor Period David Schwope, Graduate Assistant, Department of English and Foreign Languages Abstract The Tudor period was a time of great change; not only was the Renaissance a time of new philosophy, literature, and art, but it was a time of technological innovation as well. Henry VII took the throne of England in typical medieval style at Bosworth Field: mounted knights in chivalric combat, much like those depicted in Malory’s just published Le Morte D’Arthur. By the end of Elizabeth’s reign, warfare had become dominated by muskets and cannons. This shift in war tactics was the result of great movements towards the use of projectile weapons, including the longbow, crossbow, and early firearms. Firearms developed in intermittent bursts; each new innovation rendered the previous class of firearm obsolete. The medieval knight was unable to compete with the new technology, and in the course of a century faded into obsolescence, only to live in the hearts, minds, and literature of the people. 131 Academic Forum 21 2003-04 In the history of warfare and other man-vs.-man conflicts, often it has been as much the weaponry of the combatants as the number and tactics of the opposing sides that determined the victor, and in some cases few defeated many solely because of their battlefield armaments. Ages of history are named after technological developments: the Stone Age, Bronze Age, and Iron Age. Our military machine today is comprised of multi-million dollar airplanes that drop million dollar smart bombs and tanks that blast holes in buildings and other tanks with depleted uranium projectiles, but the heart of every modern military force is the individual infantryman with his individual weapon. -

Fire-Making Apparatus in the U.S. National Museum

loo I CD •CD CO Hough, Walter Fire-making apparatus in the U.S. National Museiiin GN 417 H68 1890 ROBA II Digitized by the Internet Archive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation http://www.archive.org/details/firemakingapparaOOhouguoft /e9o FIRE-MAKING APPARATUS IN THE U. S. N By Walter HougM. AnT O R OCT 2 5 1973 Man ,n h.s onginals seems to be a thing unarn.ed ^Sj^^LViM „™Ww to Ll„ tse f, as needing the aid of ,na„y things; therefore Pro^nl^fi^ii^Wht,; ^ A^^ ont hre wh.eh snppediates and yields eomfort and help in a wants and mannerto hulu necessit.es; so that if the soul be the form I of forms, and the hand be .he ,netr„,„e„tof mstrnmeuts,rtre deserves well to be ealled the suecorof sn eors the help of helps, or that infinite ways afford aid and assistance to all labors and ihe There is a prevalent belief that to make fire by rubbing o two pieces wood .s very d.ffienlt. It is not so, the writer has repeftedly n,rde ^ *''''""^ ^ *"' '""^^ ''"'' «"« ^^*^<'°"'J« ^'tb th« fow drSl '" *''^ ''^^^ ^"^^ ^''"°"« wifhTl-?nf"*''' r^'^t*'''" P^oP'e^ ""^te fire ''*"*^" ^'* '''''^'"«'' and IroqlTs! '"" ^ ' '» *''« ^urons They take two pieces of cedar wood drvanfllio-lif- fTinxr 1,^1/1 • /> , All these descriptions omit details that are essential h to the comore ns,on ot the reacler. There is a great knack in twiriing the veXal .stick. It ,s taken be( ween the paln.s of the outstretched hands which a o drawn backwards and forwards past each other almost tTth;!!^; t thus PS, g, vmg the driU a reciprocating motion. -

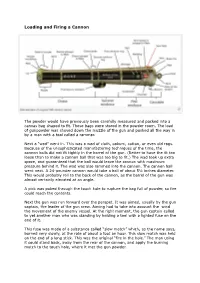

Loading and Firing a Cannon

Loading and Firing a Cannon The powder would have previously been carefully measured and packed into a canvas bag shaped to fit. These bags were stored in the powder room. The load of gunpowder was shoved down the muzzle of the gun and pushed all the way in by a man with a tool called a rammer. Next a “wad” went in. This was a wad of cloth, oakum, cotton, or even old rags. Because of the unsophisticated manufacturing techniques of the time, the cannon balls did not fit tightly in the barrel of the gun. (Better to have the fit too loose than to make a cannon ball that was too big to fit.) The wad took up extra space, and guaranteed that the ball would leave the cannon with maximum pressure behind it. The wad was also rammed into the cannon. The cannon ball went next. A 24-pounder cannon would take a ball of about 5½ inches diameter. This would probably roll to the back of the cannon, as the barrel of the gun was almost certainly elevated at an angle. A pick was poked through the touch hole to rupture the bag full of powder, so fire could reach the contents. Next the gun was run forward over the parapet. It was aimed, usually by the gun captain, the leader of the gun crew. Aiming had to take into account the wind the movement of the enemy vessel. At the right moment, the gun captain called to yet another man who was standing by holding a tool with a lighted fuse on the end of it. -

CONTINENTAL LINE Safety Guide to Black Powder

CONTINENTAL LINE Safety Guide to Black Powder GENERAL GUIDELINES These guidelines apply to the use of Black Powder firearms for historical demonstration purposes by Continental Line (C.L.) Member Units. "Member Units" mean an organization that is recognized by the C.L. and is officially enrolled as such, or any unit that is a guest of the C.L. "Demonstration" means the loading and firing of a black powder weapon, for the purpose of puBlic education, under the direction of a Safety Officer. Every MemBer Unit is reQuired to have a Safety Officer. This individual is thoroughly knowledgeable of the Safety Standard and Guide to Black Powder. This individual is directly responsiBle for the weapons and/or Artillery Piece and how they are used by the memBers of their own Unit. This individual is answerable to the C.L. for any compromise or violation of these Guidelines, and has signed a statement declaring such. Only two types of weapons may Be fired By Member Units: muzzleloading Black powder flintlocks, and full-scale muzzleloading cannons. Pistols may NOT be fired in demonstrations except by Mounted Troops with approval of the Field Commander. Edged weapons, swords, knives, tomahawks, etc. must always Be considered dangerous. Except for use as a camp tool, they should never Be unsheathed. The two types of weapon demonstrations permitted are; Individual Demonstrations and Tactical Demonstrations. Individual Demonstrations are demonstrations during which a single weapon is loaded and fired by a member or, in the case of a cannon, a crew of members. Tactical Demonstrations are those where two or more weapons are loaded and fired under simulated Battle conditions. -

(Inclmifiei the GENERAL SERVICE SCHOOLS LIBRARY

~-~~-~ j^j^ 101949 . BOXBOX tUMBESTtUMBEST J NOTES ON SIGNAL AND ILLUMINATING ILLUMINATING DEVICES AND THE APPARATUS APPARATUS FOR PROJECTING THEM THEM iv, -d-d FROM THE FRENCH EDITION OF 1911 1 7u "" 4 AT TRANSLATED AND EDITED AT THE 3 ~5~5 ARMY WAR COLLEGE 3 3 —— -3 a on nn MAY,1917 |3 j tf to ffl UL j WASHINGTON Q34 GOVERNMENT PRINTING OFFICE 19171917 (INCLmiFIEI THE GENERAL SERVICE SCHOOLS LIBRARY CLASS NUMBER__ H_9tO3-_Bls_ Accession Number____ ifZcr*: eral. WAR DEPARTMENT, Washington, May 23, 1917. The following notes on signal and illuminating devices and the apparatus for projecting them are published for the information of allconcerned. [2605615, A.G. o.] order op the Secretary of War: TASKER H. BLISS, Major General, Acting Chief ofStaff. Official: h. p. McCain, The Adjutant General. 3 NOTES ON SIGNAL AND ILLUMINATINGDEVICES AND APPARATUS FOR PROJECTING THEM. The various devices forsignal and illuminatingpurposes are classi fied as follows:1 I. SIGNAL DEVICES. i-tIXiiIUUJCjO Cartridges for the— Rockets.Rockets. V.-B.gun.V.-B.gun. 25-mm. pistol. 35-mm. pistol. Large white stars White parachute. .'' Large red stars Red parachute Redstars Large green stars Green parachute .. GreenstarsGreenstars DoDo 1star Illuminating,with- 1star. out parachute* DoDo 2 stars. DoDo 3stars3stars 3 stars 3 stars. DoDo 6stars6stars 6 stars 6 stars. "Chenile" (a caterpillar ChenileChenile ChenileChenile Chenile.Chenile. rocket).rocket). Red smoke Red smoke Red smoke Red smoke. Yellow smoke , Yellowsmoke Yellow smoke Yellow smoke. "Drapeau" (flag) B. BENGAL LIGHTS.—White a: id red, 30 seconds. 1This list willbe changed from time to tin te to keep pace with the development md manufacture of new devices. -

Fire-Making Apparatus in the U. S. National Museum

— FIRE-MAKING APPARATUS IN THE U. S. NATIONAL MUSEUM. By Walter Hough. Man in his originals seems to be a thing unarmed and naked, and unable to help itself, as needing the aid of many things; therefore Prometheus makes haste to find out fire, which suppediates and yields comfort and help in a manner to all human wants and necessities; so that if the soul be the form of forms, and the hand be ihe instrument of instruments, fire deserves well to be called the succor of succors, or the help of helps, that infinite ways aff'ord aid and assistance to all labors and the mechanical arts, and to the sciences themselves. Bacon.— Wisdom of the ancients, Prometheus, Works, vol. iii. Lond., 1825, p. 72. There is a prevalent belief that to make fire by rubbing two pieces of wood is very difficult. It is not so; the writer has repeatedly made fire in thirty seconds by the twirling sticks and in five seconds with the bow drill. Many travelers relate that they have seen various peoples make fire with sticks of wood. The most common way, by twirling one stick upon another is well described by Pere Latitau with reference to the Hurons and Iroquois. They take two pieces of cedar wood, dry and light ; they hold one piece firmly down with the knee and in a cavity which they have made with a beaver-tooth or with the point of a knife on the edge of one of these pieces of wood which is flat and a little larger, they insert the other piece which is round and pointed and turn and press down with so much rapidity and violeuce that the material of the wood agi- tated with vehemence falls off in a rain of fire by means of a crack or little canal which leaps from the cavity over a match [slow match].