To What Extent Can a Person Be Liable for the Criminal Act Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Preparing Tomorrow's Lawyers to Tackle Twenty-First Century Health and Social Justice Issues

Denver Law Review Volume 95 Issue 3 Article 2 November 2020 Preparing Tomorrow's Lawyers to Tackle Twenty-First Century Health and Social Justice Issues Jennifer Rosen Valverde Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.du.edu/dlr Recommended Citation Jennifer Rosen Valverde, Preparing Tomorrow's Lawyers to Tackle Twenty-First Century Health and Social Justice Issues, 95 Denv. L. Rev. 539 (2018). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Digital Commons @ DU. It has been accepted for inclusion in Denver Law Review by an authorized editor of Digital Commons @ DU. For more information, please contact [email protected],[email protected]. PREPARING TOMORROW'S LAWYERS TO TACKLE TWENTY-FIRST CENTURY HEALTH AND SOCIAL JUSTICE ISSUES JENNIFER ROSEN VALVERDEt ABSTRACT Changing times require changes to the ways in which lawyers, define, approach, and address complex problems. Legal education reform is needed to properly equip tomorrow's lawyers with the knowledge and skills necessary to address twenty-first century issues. This Article pro- poses that the legal academy foster the development of competencies in preventive law, interdisciplinary collaboration, and community engage- ment to prepare lawyers adequately for the practice of law. The Article offers one model for so doing-a law school-based medical-legal partner- ship clinic-and discusses the benefits, challenges, and lessons learned from the author's own experience teaching in such a program. However, the Article proposes that the clinic model is merely a starting point, and that law schools should integrate instruction in preventive law, interdisci- plinary collaboration, and community engagement throughout the curric- ulum in a carefully designed progression to achieve the curricular reform needed to properly prepare tomorrow's lawyers. -

Common Purpose and Conspiracy Liability in New Zealand: Criminality by Association?

Common Purpose and Conspiracy Liability in New Zealand: Criminality by Association? Julia Tolmie and Kris Gledhill* Case law interpreting the common purpose aspect of party liability and the law on conspiracy in New Zealand (as set out in ss 66(2) and 310 of the Crimes Act 1961 (NZ)) has created a situation of over-reach. Individuals who have a limited relationship to criminality carried out by another or in a group context are potentially caught by extended liability rules that can lead to a poor association between the moral culpability of a defendant and serious criminal liability. Indeed, it is suggested that these forms of liability risk guilt by association rather than on the basis of individual positive fault: we suggest that New Zealand’s judges, following and sometimes expanding upon interpreta- tions from other common law jurisdictions, have lost sight of the core concept of individual fault. I INTRODUCTION A fundamental premise of the criminal law is that an individual’s liability (and resulting punishment) is based on their own individual action and personal fault: association with criminals is not itself criminal unless specified circumstances are met.1 This substantive rule is reinforced by rules of procedure and evidence that protect against guilt by association. A prime example is the caution in using hearsay evidence, things said outside the presence of the defendant. Having said this, there are offences based on joint liability and liability for participation in another’s offending. These recognise that group dynamics or support may elevate the risk and seriousness of the principal’s offending. -

The Doctrine of Common Purpose: a Brief Historical Perspective; the Common Purpose Doctrine Defined and a Focus on Withdrawal from the Common Purpose

1 THE DOCTRINE OF COMMON PURPOSE: A BRIEF HISTORICAL PERSPECTIVE; THE COMMON PURPOSE DOCTRINE DEFINED AND A FOCUS ON WITHDRAWAL FROM THE COMMON PURPOSE BY NESIRA SINGH STUDENT NUMBER 209527200 ‘THIS RESEARCH PROJECT IS SUBMITTED IN PARTIAL FULFILMENT OF THE OF THE REGULATIONS FOR THE LLM DEGREE AT THE UNIVERSITY OF KWAZULU- NATAL PIETERMARITZBURG’ SUPERVISOR : PROFESSOR SHANNON HOCTOR DECEMBER 2016 2 CONTENTS CHAPTER 1 : INTRODUCTION 1.1 Background 4 1.2 Purpose and objectives of the dissertation 6 1.3 Research Methodology 6 CHAPTER 2: A BRIEF HISTORICAL BACKGROUND AND THE DEFINITION OF COMMON PURPOSE DOCTRINE 2.1 Introduction 8 2.2 The Transkeian Penal Code 8 2.3 The early application of the doctrine through the cases 8 2.4. Definition of the common purpose 11 2.5 The Safasta decision 14 2.6 The Mgedezi decision 16 2.7 Conclusions 19 CHAPTER 3: THE CONSTITUTIONALITY OF THE DOCTRINE OF COMMON PURPOSE. 3.1 Introduction 20 3.2 Facts of the Thebus case 21 3.3 Criticism of the Thebus case 24 3.4 Justification for the doctrine of common purpose 25 3.5 Conclusion 26 3 CHAPTER 4: DISSOCIATION FROM THE COMMON PURPOSE 4.1 Introduction 27 4.2 What constitutes withdrawal from common purpose 27 4.2.1 The intention to withdraw 28 4.2.2. A positive act 33 4.2.3 Voluntariness to withdraw 34 4.2.4 Stage of withdrawal 36 4.2.5 Type of act required 36 4.2.6 Role of the accused 37 4.3. Conclusion 43 CHAPTER 5: FOREIGN JURISDICTIONS 44 5.1 Introduction 44 5.2 The English position 44 5.3 Circumstances where foreign courts consider withdrawal 48 5.3.1 Venda decisions 48 5.3.2 Zimbabwean decisions 50 5.4. -

The Leadership Challenge

Praise for the Fifth Edition of The Leadership Challenge “My heart goes out to Jim Kouzes and Barry Posner with the deepest gratitude for this book, the most powerful leadership resource available. It is providential that at a time of the lowest level of trust and the highest level of cynicism, The Leader- ship Challenge arrives with its message of hope. When there are dark days in our lives, Kouzes and Posner will shine a light.” —Frances Hesselbein, former CEO, Girl Scouts of the USA; author, My Life in Leadership “Jim Kouzes and Barry Posner have taken one of the true leadership classics of the late twentieth century and made it freshly relevant for today’s twenty-first century leaders. It is a must-read for today’s leaders who aspire to contribute in a more significant way tomorrow.” —Douglas R. Conant, New York Times bestselling author, TouchPoints; retired CEO, Campbell Soup Company “For twenty-five years, the names Jim Kouzes and Barry Posner have been synony- mous with leadership. There is a reason for that. This book, in its new and updated form, demonstrates that leadership is a challenge you must win every day. It shows that every leader is unique, with his or her own style, and it helps you find your style. But the real beauty of this book is that it does not just tell you about leader- ship. It takes you by the hand, and walks you through the steps necessary to be better at what you do. It also gives you the confidence to take the kinds of risks every leader needs to take to succeed. -

Cook Islands Bill Template

Hon. Teariki Heather [Placeholder for Crest] Crimes Bill 2017 Contents 1 Title 10 2 Commencement 10 Part 1 Preliminary matters Subpart 1—Interpretation 3 Interpretation 11 4 Meaning of dishonest and dishonestly 19 5 Meaning of menace for this Act 19 6 Meaning of ordinarily resident for this Act 20 Subpart 2—Application of Act 7 Act binds the Crown 20 8 Criminal responsibility under more than 1 law or provision 20 9 Common law offences 20 10 Act applies to corporations 20 11 Corporation—conduct for an offence 20 12 Corporation—mental elements of intention, knowledge, or recklessness 21 13 Corporation—mental element for grossly negligent conduct 21 14 Corporation—mistake of fact—conduct to which no mental element applies 22 15 Corporation—intervening conduct or event 22 16 Corporation—penalties for offences against this Act 22 Part 2 Jurisdiction 17 Geographical application and effect of Act 22 18 Extraterritorial jurisdiction—ships or aircraft outside Cook Islands 23 19 Extraterritorial jurisdiction—transnational crime 24 20 Consent of Attorney-General required for certain prosecutions 25 21 Jurisdiction in relation to people with diplomatic or consular immunity 25 Part 3 Proof of criminal responsibility 22 Legal burden of proof—prosecution 26 23 Standard of proof—prosecution 26 24 Evidential burden of proof—defence 26 1 Crimes Bill 2017 25 Legal burden of proof—defence 26 26 Standard of proof—defence 26 27 Ignorance of the law not a defence 27 28 Proof of recklessness 27 29 Offences that do not mention mental element required for offence -

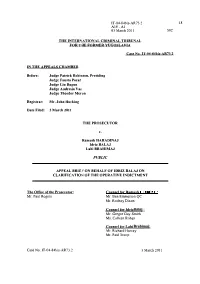

Appeal Brief on Behalf of Idriz Balaj on Clarification of the Operative

IT -04-84his-AR 73.2 18 AI8-Al 03 March 2011 MC THE INTERl'lATIONAL CRIMINAL TRIBUNAL FOR TElE FORMER YUGOSLAVIA Case No. IT-04-84bis-AR73.2 IN THE APPEALS CHAMBER Before: Judge Patrick Robinson, Presiding Judge Fausto Pocar Judge Liu Dagun Judge Andresia Va2 Judge Theodor Meron Registrar: Mr. John Hocking Date Filed: 3 March 2011 THE PROSECUTOR v. Ramush HARADINAJ Idriz BALAJ Lahi BRAHIMAJ PUBLIC APPEAL BRIEf? ON BEHALF OF IDRIZ UALAJ ON CLARIFICATION OF THE OPERATIVE INDICTMENT The Office of the Prosecutor: Counsel for Ramush Haradinaj: Mr. Paul Rogers Mr. Ben Emmerson QC Mr. Rodney Dixon Counsel for Idriz Balaj: Mr. Gregor Guy-Smith Ms. Colleen Rohan Counsel for Lahi Brahimaj: Mr. Richard Harvey Mr. Paul Troop Case No. IT-04-84bis-AR73.2 3 March 2011 17 I. Introduction 1. The issue certified for appea on behalf of Mr. Balaj raises the question of whether, at the partial retrial ordered on t1 e six counts alleging offenses at lablanica/labllanice, the prosecution is legally barred from re-alleging as part of its lCE theory, criminal conduct for which the Accused have all been acquitted pursuant to final judgements afterappeal. 2. The current version of the operative shortened indictment, filed on 21 lanuary 2011, alleges in paragraph 24: The common criminalmrpose of the lCE was to consolidate the total control of the KLA over the Dukagjin Operational Zone by the unlawful removal and mistreatment of Serb civilians and by the mistreatment of Kosovar Albanian and Kosovar Roma/Egypti m civilians, and other civilians, who were, or were perceived to have beer, collaborators with the Serbian Forces or otherwise not supporting the KLA. -

The Interplay Between International Criminal Law and Refugee Law in the Area of Extended Liability

LEGAL AND PROTECTION POLICY RESEARCH SERIES Exclusion at a Crossroads: The Interplay between International Criminal Law and Refugee Law in the Area of Extended Liability Joseph Rikhof Senior Counsel, Crimes against Humanity and War Crimes Section, Department of Justice, Canada DIVISION OF INTERNATIONAL PROTECTION June 2011 PPLA/2011/06 DIVISION OF INTERNATIONAL PROTECTION UNITED NATIONS HIGH COMMISSIONER FOR REFUGEES (UNHCR) CP2500, 1211 Geneva 2 Switzerland E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.unhcr.org This background paper was commissioned in November 2010 for the Expert Meeting on Complementarities between International Refugee Law, International Criminal Law, and International Human Rights Law, convened by UNHCR and the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda between 11 and 13 April 2011 in Arusha, Tanzania. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the positions of the Department of Justice nor the government of Canada. This paper includes excerpts from the author’s upcoming book, The Criminal Refugee: the Treatment of Asylum Seekers with a Criminal Background in International and Domestic Law (Dordrecht: Republic of Letters Publishing, 2011). This paper may be freely quoted, cited and copied for academic, educational or other non- commercial purposes without prior permission from UNHCR, provided that the source and author are acknowledged. The paper is available online at http://www.unhcr.org/protect. © United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees 2011. 2 Table of Contents -

Jason L. Brown, New Executive Director & General Counsel Of

Volume 2, Issue 3 | December 2010 Jason L. Brown, New Executive Director & General Counsel Inside this of NAMWOLF on NAMWOLF’s Past, Present and Future issue: By: Justi Miller | Kelly & Berens, P.A Message from On October 5, 2010, NAMWOLF appointed its first Executive Director the Chairman and General Counsel. Prior to accepting the position, Jason was Page 3 Director of Legal/Senior Counsel - Domestic and Caribbean, PepsiAmericas, Inc. where he handled litigation, risk management, Article: Tried government relations, promotional/sweepstakes issues, negotiating and and True drafting customer and vendor agreements, corporate compliance and fraud, and a variety of other legal issues. He also served as president Tactics for of the PepsiAmericas Foundation. Expediting Contract Jason L. Brown Jason graduated from Howard University School of Law in Washington, Negotiations D.C. He began his legal career as an associate at the law firm of Page 6 Winthrop & Weinstine, P.A. in Minneapolis then joined the law firm of Ungaretti & Harris in Chicago in 2000. Spotlight: Jason, prior to this appointment, what has been your involvement with NAMWOLF? Member Initially, when I was with PepsiAmericas, I was their contact to NAMWOLF. Then in 2004, Firm I was invited to join NAMWOLF’s Advisory Council, which consists of in-house attorneys Page 8 who have expressed a desire and commitment to help NAMWOLF reach its goals. A little over a year later, in 2005 and prior the very first annual meeting, I was asked to chair the Advisory Council. Then in about 2007, I joined the board of directors when NAMWOLF Law Firm News included an in-house person on the board. -

The "Perjury Trap"

[Vol. 129:624 THE "PERJURY TRAP" BENNETT L. GERSHMAN t "Any experienced prosecutor will admit that he can indict anybody at any time for almost anything before any grand jury." 1 "Save for torture, it would be hard to find a more effective tool of tyranny than the power of unlimited and un- checked ex parte examination." 2 Most experienced prosecutors would reject as nonsense the notion that they could indict anybody at any time for anything before any grand jury. They would, however, probably concede that their marksmanship improves when perjury is sought.3 That is the subject of this Article: the deliberate use of the grand jury to secure perjured testimony, a practice dubbed by some courts the "perjury trap." 4 f Associate Professor of Law, Pace University. A.B. 1963, Princeton University; L.L.B. 1966, New York University. The author gratefully acknowledges the assistance of his colleague Professor Judith Schenck Koffier. This Article is dedicated to Professor Robert Childres. I Campbell, Delays in Criminal Cases, 55 F.R.D. 229, 253 (1972), quoted in United States v. Mara, 410 U.S. 19, 23 (1973) (Douglas, J., dissenting) (identical dissenting opinion in United States v. Dionisio, 410 U.S. 1, 18 (1973)). 2 United States v. Remington, 208 F.2d 567, 573 (2d Cir. 1953) (L. Hand, J., dissenting), cert. denied, 347 U.S. 913 (1954). 3 "Perjury" is used in this Article to mean a witness's deliberately false swear- ing to a material matter in a judicial proceeding, here specifically a grand jury. Defined as such, six elements are required to prove perjury: (1) an oral statement; (2) that is false; (3) made under oath; (4) with knowledge of its falsity; (5) in a judicial proceeding such as a grand jury; (6) to a material matter. -

Common Purpose’: the Crowd and the Public

‘Common Purpose’: The Crowd and the Public Ulrike Kistner* *U. Kistner Department of Philosophy, University of Pretoria, Private Bag X20, Hatfield, Pretoria 2008, South Africa e-mail: [email protected] Abstract The legal doctrine of ‘common purpose’ in South African criminal law considers all parties liable who have been in implicit or explicit agreement to commit an unlawful act, and associated with each other for that purpose, even if the consequential act has been carried out by one of them. It relieves the prosecution of proving the causal link between the conduct of an individual member of a group acting in common purpose, and the ultimate consequence caused by the action of the group as a whole. The National Prosecuting Authority’s controversial and vociferously challenged decision (initially upheld, then withdrawn at the beginning of September 2012) to charge 270 demon- strators at Lonmin Platinum Mine in Marikana with the murders of 34 colleagues under the ‘common purpose’ doctrine, implying liability by association or agreement, raises the question as to the constitution and characteristics of the crowd and of the public, respectively. This article outlines the history of the application of the common purpose rule in South Africa, to then examine ‘common purpose’ within the philosophical parameters of group psychology and collective intentionality. It argues for methodological individualism within a psychoanalytic theorisation of group dynamics, and a non-summative approach to collective intentionality, in addressing some problems in the conceptualisation of group formation. Keywords Collective action Á Common purpose Á Complicity Á Group psychology Á Implied mandate Á Imputation of liability Á Individual psychology Á Intention 1 The decision by South Africa’s National Prosecution Authority (NPA)1 to charge 270 arrested miners who had been demonstrating at Lonmin Platinum Mine in Marikana with the murders of 34 colleagues who had been shot by the police on 16 August 2012, was met with a public outcry at the time. -

The Doctrine of Swart Gevaaar to the Doctrine of Common Purpose: A

THE DOCTRINE OF SWART GEVAAR TO THE DOCTRINE OF COMMON PURPOSE: A CONSTITUTIONAL AND PRINCIPLED CHALLENGE TO PARTICIPATION IN A CRIME By YUSHA DAVIDSON BCom Economics and Law (UCT); LLB (UCT) A dissertation submitted in fulfilment of the degree MASTER OF LAWS BY RESEARCH In the Faculty of Law, University of Cape Town Town Under the supervisionCape of PAMELA JANEof SCHWIKKARD Professor of Law JAMEELAH OMAR Lecturer of Law University University of Cape Town 24 JULY 2017 The copyright of this thesis vests in the author. No quotation from it or information derived from it is to be published without full acknowledgement of the source. The thesis is to be used for private study or non- commercial research purposes only. Published by the University of Cape Town (UCT) in terms of the non-exclusive license granted to UCT by the author. University of Cape Town DECLARATION I, the undersigned, YUSHA DAVIDSON, hereby declare that: 1. The research reported in this dissertation, except where otherwise indicated, is my original work. 2. This dissertation has not been submitted for any degree or examination at any other university. 3. This dissertation does not contain other persons’ writing, unless specifically acknowledged as being sourced from other researchers. Where other written sources have been quoted, then: a) their words have been re-written but the general information attributed to them has been referenced; b) where their exact words have been used, their writing has been clearly indicated as a quotation and referenced. SIGNED ________________________ Y DAVIDSON i To all those convicted under the doctrine of common purpose A luta continua ii ABSTRACT Swart gevaar was a term used during apartheid to refer to the perceived security threat of the majority black African population to the white South African government and the white minority population. -

Counsel for Hashim Thaҫi Jack Smith David Hooper

KSC-BC-2020-06/F00297/1 of 12 PUBLIC 14/05/2021 12:31:00 In: KSC-BC-2020-06 Specialist Prosecutor v. Hashim Thaçi, Kadri Veseli, Rexhep Selimi and Jakup Krasniqi Before: Pre-Trial Judge Judge Nicolas Guillou Registrar: Dr Fidelma Donlon Filing Participant: Counsel for Rexhep Selimi Date: 14 May 2021 Language: English Classification: Public Selimi Defence Reply to SPO Response to Defence Challenge to the Form of the Indictment Specialist Prosecutor Counsel for Hashim Thaҫi Jack Smith David Hooper Counsel for Kadri Veseli Ben Emmerson Counsel for Rexhep Selimi David Young Counsel for Jakup Krasniqi Venkateswari Alagendra KSC-BC-2020-06 1 14 May 2021 KSC-BC-2020-06/F00297/2 of 12 PUBLIC 14/05/2021 12:31:00 I. INTRODUCTION 1. Pursuant to Rule 76 of the Rules1 and the Scheduling Order issued by the Pre-Trial Judge,2 the Defence for Mr. Rexhep Selimi hereby replies to the new issues raised in the Specialist Prosecutor’s Response3 to the Defence Challenge to the Form of the Indictment4, concerning the Indictment submitted by the SPO to the Pre-Trial Judge on 24 April 2020, revised on 24 July 20205 and confirmed by the Pre-Trial Judge on 26 October 2020.6 2. This Reply addresses the following issues which all arise directly from the Response: (1) the erroneous interpretation of materials facts and underlying evidence; (2) the impact of the redactions on the overall form of the indictment; (3) the alleged compensatory effect of disclosed materials to resolve ambiguities in the Indictment; (4) the SPO’s repeated prejudicial use of non-exclusive language in the indictment; (5) the SPO’s mutually exclusive alternative charging on Joint Criminal Enterprise (“JCE”) in relation to membership and foreseeable crimes; and, (6) the SPO’s failure to adequately specify Mr.