The Alekhine Defence Move by Move

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA

First Steps : Fundamental Endings CYRUS LAKDAWALA www.everymanchess.com About the Author Cyrus Lakdawala is an International Master, a former National Open and American Open Cham- pion, and a six-time State Champion. He has been teaching chess for over 30 years, and coaches some of the top junior players in the U.S. Also by the Author: Play the London System A Ferocious Opening Repertoire The Slav: Move by Move 1...d6: Move by Move The Caro-Kann: Move by Move The Four Knights: Move by Move Capablanca: Move by Move The Modern Defence: Move by Move Kramnik: Move by Move The Colle: Move by Move The Scandinavian: Move by Move Botvinnik: Move by Move The Nimzo-Larsen Attack: Move by Move Korchnoi: Move by Move The Alekhine Defence: Move by Move The Trompowsky Attack: Move by Move Carlsen: Move by Move The Classical French: Move by Move Larsen: Move by Move 1...b6: Move by Move Bird’s Opening: Move by Move Petroff Defence: Move by Move Fischer: Move by Move Anti-Sicilians: Move by Move Opening Repertoire ... c6 First Steps: the Modern 3 Contents About the Author 3 Bibliography 5 Introduction 7 1 Essential Knowledge 9 2 Pawn Endings 23 3 Rook Endings 63 4 Queen Endings 119 5 Bishop Endings 144 6 Knight Endings 172 7 Minor Piece Endings 184 8 Rooks and Minor Pieces 206 9 Queen and Other Pieces 243 4 Introduction Why Study Chess at its Cellular Level? A chess battle is no less intense for its lack of brevity. Because my messianic mission in life is to make the chess board a safer place for students and readers, I break the seal of confessional and tell you that some students consider the idea of enjoyable endgame study an oxymoron. -

Kasparov's Nightmare!! Bobby Fischer Challenges IBM to Simul IBM

California Chess Journal Volume 20, Number 2 April 1st 2004 $4.50 Kasparov’s Nightmare!! Bobby Fischer Challenges IBM to Simul IBM Scrambles to Build 25 Deep Blues! Past Vs Future Special Issue • Young Fischer Fires Up S.F. • Fischer commentates 4 Boyscouts • Building your “Super Computer” • Building Fischer’s Dream House • Raise $500 playing chess! • Fischer Articles Galore! California Chess Journal Table of Con tents 2004 Cal Chess Scholastic Championships The annual scholastic tourney finishes in Santa Clara.......................................................3 FISCHER AND THE DEEP BLUE Editor: Eric Hicks Contributors: Daren Dillinger A miracle has happened in the Phillipines!......................................................................4 FM Eric Schiller IM John Donaldson Why Every Chess Player Needs a Computer Photographers: Richard Shorman Some titles speak for themselves......................................................................................5 Historical Consul: Kerry Lawless Founding Editor: Hans Poschmann Building Your Chess Dream Machine Some helpful hints when shopping for a silicon chess opponent........................................6 CalChess Board Young Fischer in San Francisco 1957 A complet accounting of an untold story that happened here in the bay area...................12 President: Elizabeth Shaughnessy Vice-President: Josh Bowman 1957 Fischer Game Spotlight Treasurer: Richard Peterson One game from the tournament commentated move by move.........................................16 Members at -

The Exchange French Comes to Life

The Exchange French Comes to Life Fresh Strategies to Play for a Win Alex Fishbein Foreword by John Watson 2021 Russell Enterprises, Inc. Milford, CT USA 1 1 The Exchange French Comes to Life Fresh Strategies to Play for a Win ISBN: 978-1-949859-29-4 (print) ISBN: 978-1-949859-30-0 (eBook) © Copyright 2021 Alex Fishbein All Rights Reserved No part of this book may be used, reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any manner or form whatsoever or by any means, electronic, electrostatic, magnetic tape, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the express written permission from the publisher except in the case of brief quotations embodied in critical articles or reviews. Published by: Russell Enterprises, Inc. P.O. Box 3131 Milford, CT 06460 USA http://www.russell-enterprises.com [email protected] Cover by Fierce Ponies Printed in the United States of America 2 Table of Contents Signs and Symbols 6 Preface 7 Foreword by John Watson 10 Chapter 1 Introduction to the Exchange French 13 Chapter 2 The IQP-lite 33 Chapter 3 The Uhlmann Gambit 72 Chapter 4 Symmetrical Structures 95 Chapter 5 The 5...c5 Variation 139 Chapter 6 The 4...Bg4 Variation 149 Chapter 7 The 4...Nc6 Variation 163 Chapter 8 Rare Moves against 4.Nf3 190 Chapter 9 The Miezis Variation 199 Chapter 10 The Delayed Exchange Variation 211 3 The Exchange French Comes to Life Chapter 11 Your Repertoire File 224 Index of Variations 235 Bibliography 239 Frequently Occurring Strategic Themes 240 4 Preface The Exchange French is nothing close to a draw! The Exchange French has long had the reputation of a boring and drawish opening. -

Bearspaw Junior Chess Club Curriculum

Bearspaw Junior Chess Club Curriculum Levels Basic Concepts Checkmates Strategy Tactics • The Pieces • Check • Shrinking the opposing • Escaping from check • How They Move • Checkmate King’s space Run Away, • Setting up the • Stalemate • Creating Escape Squares Block, board Capture Special Moves • Fool’s mate Basic Opening Strategy • Hanging Piece (Piece En Novice • Castling • Scholar’s • Attack the Center with Prise) • Promotion mate Center Pawns Level 2 • En Passant • Solo/Helper • Knights & Bishops out early mates • Castle for King safety • Computer and • Rooks connected Online Chess • Value of pieces • Two Rooks • Attack f7/f2 • Relative Exchanges Novice • Etiquette or Queen • Piece Preferences • Winning the Exchange • Touch move and Rook (outposts, open files, (capturing more or Level 3 • Release move • Back rank batteries, fianchetto, better pieces) • Tournaments mates a Knight on the rim, • Simplify when up • Using clocks hide or centralize the King) material Copyright @ 2018 Bearspaw Junior Chess Club – All Rights Reserved. Bearspaw Junior Chess Club Curriculum Levels Concepts Checkmates Strategy Tactics Intermediate • Notation • King and • Critical Moves • Forks • Phases of the game Queen • Find 3 moves and • Pins Level 4 • Simple Pawn Structure • King and rate them: (Chains, Isolated, Doubled, Passed) Rook - Good, Openings - Better - Best Compare 2 openings: • Giuoco Piano • Fried Liver Attack Intermediate e4-e5 • Queen and Threat Assessment • Skewer • Bishop Bishop 1. His/her Checks… • Discovered Level 5 • Scotch • Queen and and Your Checks Attack • Danish Knight 2. His/her Captures… • Petrov and your Captures 3. His/her Threats… and your Threats Intermediate More e4-e5 • Rook and The Five Elements • Double Check • Ruy Lopez Bishop 1. -

Chesstempo User Guide Table of Contents

ChessTempo User Guide Table of Contents 1. Introduction. 1 1.1. The Chesstempo Board . 1 1.1.1. Piece Movement . 1 1.1.2. Navigation Buttons . 1 1.1.3. Board actions menu . 2 1.1.4. Board Settings . 2 1.2. Other Buttons. 4 1.3. Play Position vs Computer Button . 5 2. Tactics Training . 6 2.1. Blitz/Standard/Mixed . 6 2.1.1. Blitz Mode . 6 2.1.2. Standard Mode. 6 2.1.3. Mixed Mode . 6 2.2. Alternatives . 7 2.3. Rating System . 7 2.3.1. Standard Rating. 7 2.3.2. Blitz Rating . 8 2.3.3. Duplicate Problem Rating Adjustment. 8 2.4. Screen Controls . 9 2.5. Tactics session panel . 9 3. Endgame Training . 11 3.1. Benchmark Mode . 11 3.2. Theory Mode . 11 3.3. Practice Mode . 11 3.4. Rating System . 12 3.5. Endgame Played Move List . 13 3.6. Endgame Legal Move List. 13 3.7. Endgame Blitz Mode . 14 3.8. Play Best . 14 4. Chess Database . 16 4.1. Opening Explorer . 16 4.1.1. Candidate Move Stats. 16 4.1.2. White Win/Draw/Black Win Percentages . 17 4.1.3. Filtering/Searching and the Opening Explorer . 17 4.1.4. Explorer Stats Options . 18 4.1.5. Related Openings . 18 4.2. Game Search . 18 4.2.1. Results List . 18 4.2.2. Quick Search . 19 4.2.3. Advanced Search. 20 4.3. Games for Position . 24 4.4. Players List . 25 4.4.1. Player Search . 25 4.4.2. -

The Diplomatic Stalemate of Japan and the United States: 1941

Portland State University PDXScholar Dissertations and Theses Dissertations and Theses 5-24-1973 The diplomatic stalemate of Japan and the United States: 1941 David Hoien Overby Portland State University Follow this and additional works at: https://pdxscholar.library.pdx.edu/open_access_etds Part of the Asian History Commons, Diplomatic History Commons, Political History Commons, and the United States History Commons Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Overby, David Hoien, "The diplomatic stalemate of Japan and the United States: 1941" (1973). Dissertations and Theses. Paper 1746. https://doi.org/10.15760/etd.1746 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of PDXScholar. Please contact us if we can make this document more accessible: [email protected]. AN ABSTRACT OF THE THESIS OF David Hoien Overby for the Master of Science in Teaching History presented May 24, 1973. Title: The Diplomatic Stalemate of Japan and the United States: 1941. APPROVED BY MEMBERS OF THE THESI Bernard v. Burke, Chainnan George c. Hoffma~ ~ This thesis contends from the time of September 1940 to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the United States and Japan offered each no workable concessions that might have deterred war. A stalemate was finnly established between the two countries. The position ,of the Japanese nation was to expand and control "Greater East-Asia," while the position the United States held was one that claimed all nations should uphold certain basic principles of democracy, that all nations should honor the sanctity of treaties," and that they should treat neighboring countries in a friendly fashion. -

107-Great-Chess-Battles-Alexander

107 Great Chess Battles Alexander Alekhine Edited and translated by E G Winter i o Oxford University Press 1980 Oxford University Press, Walton Sireel, Oxford OX2 6DP OXFORD LO�DON GLASCOW NEW YORk TORONTO MELDOURNI:: WELLINGTON kUALA LUMPUR SIr-;GAPORE JAkARTA IIONG kONG DELHI BOMBAY CALCUTTA MADRAS KARACHI NAIROBI DAR ES SAI.AAM CAPE TOWN © Oxford University Pre.. 1980 All rights reserved. No part of this publication mal' be reproduced. stored in II retrieval system, or trantmitted. in any fann or by any means� electronic, mechaniCllI, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without the prior penn_ion of Oxford Univeflity PreIS This book is $Old subject to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent, re-sold� hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publisher', prior consent in any form of binding or colier other than that in which it;$ published and without II similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser. British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data Alekhin, Aleksandr Aleksandrovich 107 great chess battles. 1. Chess - Collections of games I. Title II. Winter, E G III. Hundred and seven great chess battles 794.1'5 GV1452 79-41072 ISBN 0-19-217590-4 ISBN 0-19-217591-2 Pbk Set by Hope SeTVices, Abingdon and printed in Great Britain by Lowe & Brydone Printers Ltd. Thetford, Norfolk Preface Alexander Alekhine, chess champion of the world for over sixteen years, was one of the greatest players of all time. He also wrote some of the finest chess books ever produced, of which the last published in English was MyBestGamesofChess1924- 1937 (London, 19391. -

163 Proof Games

TTHHEE PPUUZZZZLLIINNGG SSIIDDEE OOFF CCHHEESSSS Jeff Coakley PROOF GAMES Tempo Here, Tempo There number 163 August 11, 2018 The task in a proof game is to show how a given position can be reached in a legal game. The puzzles in this column have a move stipulation. The position must be reached in a precise number of moves, no more and no less. The first two problems are proof games in 4.0 which means four moves by each side. The positions may be illogical, and the strategy diabolical, but the moves are legal. Proof Game 80 w________w árhbdkgn4] à0p0pdp0p] ßwdwdwdwd] Þdwdwdwdw] ÝwdwdPdw1] ÜdwdwdQdw] ÛP)P)w)P)] Ú$NGwIBdR] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw This position, with White to play, was reached in a game after each player made exactly four moves. What were the moves? In Search of the Lost Tempo Proof Game 81 w________w árhwdkgn4] à0p0q0p0p] ßwdw0wdwd] Þdwdwdwdw] ÝPdwdwdwd] Üdwdwdwdw] Ûw)P)P)P)] Ú$NGQIBHR] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw This position was reached after Black’s fourth turn. What were the moves? A synthetic game is similar to a proof game. But instead of finding the move sequence that leads to a given position, the task is to compose a game that ends with a particular move. Synthetic Game 40 w________w árhb1kgn4] à0p0p0p0p] ßwdwdwdwd] Þdwdwdwdw] Ýwdwdwdwd] Üdwdwdwdw] ÛP)P)P)P)] Ú$NGQIBHR] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw Compose a game that ends with the move 4...Nd4# The game below is 4.5 moves. One step deeper, one step trickier. Longer Proof Game 60 (4.5 moves) w________w árhbdkgn4] à0p0wdp0p] ßwdwdpdwd] Þdwdwdwdw] Ýwdwdwdwd] Üdwdwdwdw] ÛP)w)P)P)] Ú$NGQIBHR] wÁÂÃÄÅÆÇÈw This position was reached after White’s fifth turn. -

Glossary of Chess

Glossary of chess See also: Glossary of chess problems, Index of chess • X articles and Outline of chess • This page explains commonly used terms in chess in al- • Z phabetical order. Some of these have their own pages, • References like fork and pin. For a list of unorthodox chess pieces, see Fairy chess piece; for a list of terms specific to chess problems, see Glossary of chess problems; for a list of chess-related games, see Chess variants. 1 A Contents : absolute pin A pin against the king is called absolute since the pinned piece cannot legally move (as mov- ing it would expose the king to check). Cf. relative • A pin. • B active 1. Describes a piece that controls a number of • C squares, or a piece that has a number of squares available for its next move. • D 2. An “active defense” is a defense employing threat(s) • E or counterattack(s). Antonym: passive. • F • G • H • I • J • K • L • M • N • O • P Envelope used for the adjournment of a match game Efim Geller • Q vs. Bent Larsen, Copenhagen 1966 • R adjournment Suspension of a chess game with the in- • S tention to finish it later. It was once very common in high-level competition, often occurring soon af- • T ter the first time control, but the practice has been • U abandoned due to the advent of computer analysis. See sealed move. • V adjudication Decision by a strong chess player (the ad- • W judicator) on the outcome of an unfinished game. 1 2 2 B This practice is now uncommon in over-the-board are often pawn moves; since pawns cannot move events, but does happen in online chess when one backwards to return to squares they have left, their player refuses to continue after an adjournment. -

The 100 Endgames You Must Know Workbook

Jesus de la Villa The 100 Endgames You Must Know Workbook Practical Endgames Exercises for Every Chess Player New In Chess 2019 © 2019 New In Chess Published by New In Chess, Alkmaar, The Netherlands www.newinchess.com All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior written permission from the publisher. Cover design: Ron van Roon Translation: Ramon Jessurun Supervision: Peter Boel Editing and typesetting: Frank Erwich Proofreading: Sandra Keetman Production: Anton Schermer Have you found any errors in this book? Please send your remarks to [email protected]. We will collect all relevant corrections on the Errata page of our website www.newinchess.com and implement them in a possible next edition. ISBN: 978-90-5691-817-0 Contents Explanation of symbols..............................................6 Introduction .......................................................7 Chapter 1 Basic endings .......................................13 Chapter 2 Knight vs. pawn .....................................18 Chapter 3 Queen vs. pawn .....................................21 Chapter 4 Rook vs. pawn.......................................24 Chapter 5 Rook vs. two pawns ..................................33 Chapter 6 Same-coloured bishops: bishop + pawn vs. bishop .......37 Chapter 7 Bishop vs. knight: one pawn on the board . 40 Chapter 8 Opposite-coloured bishops: bishop + two pawns vs. -

Mastering the Transition Into the Pawn Ending PDF Book

LIQUIDATION ON THE CHESS BOARD: MASTERING THE TRANSITION INTO THE PAWN ENDING PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Joel Benjamin | 224 pages | 22 Mar 2016 | New in Chess | 9789056915537 | English | Poland Liquidation on the Chess Board: Mastering the Transition Into the Pawn Ending PDF Book Hilbert Stephan marked it as to-read Sep 21, To ensure we are able to help you as best we can, please include your reference number:. It is a vital technique that is seldom taught. Your email address will never be sold or distributed to a third party for any reason. Benjamin has managed to create an excellent guide to a difficult theme that has been badly served in chess literature. Text will be unmarked. Walmart Services. Show More Show Less. Friend Reviews. Aymen rated it it was amazing Apr 14, Thank you. New edition published , softback, pages.. Skip to the end of the images gallery. Before emerging as endgames with just kings and pawns, they 'pre-existed' in positions that still contained any number of pieces. Liquidation is the purposeful transition into a pawn ending. About Joel Benjamin. It is a vital technique that is seldom taught. To ask other readers questions about Liquidation on the Chess Board , please sign up. New Products. This item doesn't belong on this page. Robert Buice marked it as to-read Feb 22, Skip to the beginning of the images gallery. Table Top Chess Computers. Get to Know Us. A ground-breaking, entertaining and instructive guide. Edwin Meijer marked it as to-read Jan 22, Specifications Publisher New in Chess. -

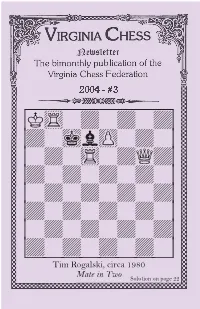

2004-3 Layout

2004 ‐ #3 ‹óóóóóóóó‹ õÚ΋›‹›‹›ú õ›‹ıËfl‹›‹ú õ‹›‹Î‹›Ó›ú õ›‹›‹›‹›‹ú õ‹›‹›‹›‹›ú õ›‹›‹›‹›‹ú õ‹›‹›‹›‹›ú õ›‹›‹›‹›‹ú ‹ìììììììì‹Tim Rogalski, circa 1980 Mate in Two Solution on page 22 VIRGINIA CHESS Newsletter 2004 - Issue #3 Editor: Circulation: Macon Shibut Ernie Schlich 8234 Citadel Place 1370 South Braden Crescent Vienna VA 22180 Norfolk VA 23502 [email protected] [email protected] Ú Í Virginia Chess is published six times per year by the Virginia Chess Federation. VCF membership dues ($10/yr adult; $5/yr junior) include a subscription to Virginia Chess. Send material for publication to the editor. Send dues, address changes, etc to Circulation. The Virginia Chess Federation (VCF) is a non- profit organization for the use of its members. Dues for regular adult membership are $10/yr. Junior memberships are $5/yr. President: Mike Atkins, PO Box 6139, Alexandria VA 22306, [email protected] Treasurer: Ernie Schlich, 1370 South Braden Crescent, Norfolk VA 23502, [email protected] Secretary: Helen Hinshaw, 3430 Musket Dr, Midlothian VA 23113, [email protected] Scholastics Chairman: Mike Cornell, 12010 Grantwood Drive, Fredericksburg VA 22407, [email protected] VCF Inc. Directors: Helen Hinshaw (Chairman), Mark Johnson, Mike Atkins, Ernie Schlich. ‡ Ï ‰ Ë Ù Ú Ó Ê ‚ Í fi 2004 - #3 1 ‡ Ï ‰ Ë Ù Ú Ó Ê ‚ Í fi 2004 Virginia Open by Mike Atkins HERE WERE TWO STORIES for this year’s Virginia Open, Tcontested June 18-20 in Springfield. One was the date change to June, as an experiment, running the event as a warm up for the World Open.