Level and Determinants of Food Insecurity in East and West Gojjam Zones of Amhara Region, Ethiopia: a Community Based Comparativ

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Districts of Ethiopia

Region District or Woredas Zone Remarks Afar Region Argobba Special Woreda -- Independent district/woredas Afar Region Afambo Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Asayita Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Chifra Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Dubti Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Elidar Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Kori Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Mille Zone 1 (Awsi Rasu) Afar Region Abala Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Afdera Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Berhale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Dallol Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Erebti Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Koneba Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Megale Zone 2 (Kilbet Rasu) Afar Region Amibara Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Awash Fentale Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Bure Mudaytu Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Dulecha Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Gewane Zone 3 (Gabi Rasu) Afar Region Aura Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Ewa Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Gulina Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Teru Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Yalo Zone 4 (Fantena Rasu) Afar Region Dalifage (formerly known as Artuma) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Dewe Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Hadele Ele (formerly known as Fursi) Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Simurobi Gele'alo Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Afar Region Telalak Zone 5 (Hari Rasu) Amhara Region Achefer -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Angolalla Terana Asagirt -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Artuma Fursina Jile -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Banja -- Defunct district/woredas Amhara Region Belessa -- -

Knowledge Management Activities

Annex 1 PLW Knowledge Management Activities Knowledge Management Amhara Regional State Bure PLW Knowledge Gap Assessment Bread Wheat Farmers are unaware of the availability of improved varieties of bread wheat and plant their whole field with one improved variety which has sprouting problem. To solve this problem the project introduced seven improved varieties and demonstrated on framers field at three sites. When using herbicides, most farmers do not know about the appropriate types of nozzles to use for different applications and calibration techniques. The project trained cooperative store-men, DAs, supervisors and experts on pesticide handling and sprayer maintenance. Farmers thresh their wheat on the ground using ox since they do not know the effect of this practice on bread quality. As a result some wheat flour factories buy grains from other suppliers at relatively higher price compared to the local market. To solve this problem the project introduced and demonstrated mechanical wheat thresher to farmers, multipurpose cooperative officials, teachers and students at two PAs. Bure Farmers did not know about the importance of minimum tillage for wheat production. As a result farmers spend a lot of money and labor for cultivation. In addition, female headed or poor households rent their land due to shortage of draught power for land preparation. On top of this, frequent cultivation aggravates soil erosion and contributes to rivers and spring siltation. To solve this problem the project demonstrated wheat production with minimum or zero tillage technology. Hot pepper Farmers did not know about availability of many improved varieties of hot pepper. To solve this knowledge gap IPMS project introduced hot pepper seed production scheme on farmers’ fields. -

Feasibility Study for a Lake Tana Biosphere Reserve, Ethiopia

Friedrich zur Heide Feasibility Study for a Lake Tana Biosphere Reserve, Ethiopia BfN-Skripten 317 2012 Feasibility Study for a Lake Tana Biosphere Reserve, Ethiopia Friedrich zur Heide Cover pictures: Tributary of the Blue Nile River near the Nile falls (top left); fisher in his traditional Papyrus boat (Tanqua) at the southwestern papyrus belt of Lake Tana (top centre); flooded shores of Deq Island (top right); wild coffee on Zege Peninsula (bottom left); field with Guizotia scabra in the Chimba wetland (bottom centre) and Nymphaea nouchali var. caerulea (bottom right) (F. zur Heide). Author’s address: Friedrich zur Heide Michael Succow Foundation Ellernholzstrasse 1/3 D-17489 Greifswald, Germany Phone: +49 3834 83 542-15 Fax: +49 3834 83 542-22 Email: [email protected] Co-authors/support: Dr. Lutz Fähser Michael Succow Foundation Renée Moreaux Institute of Botany and Landscape Ecology, University of Greifswald Christian Sefrin Department of Geography, University of Bonn Maxi Springsguth Institute of Botany and Landscape Ecology, University of Greifswald Fanny Mundt Institute of Botany and Landscape Ecology, University of Greifswald Scientific Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Michael Succow Michael Succow Foundation Email: [email protected] Technical Supervisor at BfN: Florian Carius Division I 2.3 “International Nature Conservation” Email: [email protected] The study was conducted by the Michael Succow Foundation (MSF) in cooperation with the Amhara National Regional State Bureau of Culture, Tourism and Parks Development (BoCTPD) and supported by the German Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (BfN) with funds from the Environmental Research Plan (FKZ: 3510 82 3900) of the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU). -

Addis Ababa University School of Graduate Studies College of Social Science Department of Social Anthropology

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY MA Thesis On The Socio-Cultural Aspects of Building Climate Resilience in the Face of Changing Environment among Agricultural Communities in the Blue Nile Basin By: Endeshaw Belay Submitted to: The School of Graduate Studies of Addis Ababa University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Art in Social anthropology Advisor: Guday Emirie (PhD) Department of Social Anthropology Faculty of Social sciences Addis Ababa University June 2014 Addis Ababa, Ethiopia ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY SCHOOL OF GRADUATE STUDIES COLLEGE OF SOCIAL SCIENCE DEPARTMENT OF SOCIAL ANTHROPOLOGY The Socio-Cultural Aspects of Building Climate Resilience in the Face of Changing Environment among Agricultural Communities in the Blue Nile Basin By: Endeshaw Belay APPROVED BY BOARD OF EXAMINERS: ADVISOR:___________________SIGNATURE__________ EXAMINER:_________________SIGNATURE___________ EXAMINER:_________________SIGNATURE___________ Table of Contents Topic Page Acknowledgments …………………………………………………………………………………….I Acronyms………………………………………………………………………………………..........II Glossary of local terms………………………………………………………………………………III Abstract………………………………………………………………………………………………IV Chapter One Introduction 1.1. Background of the Study………………………….……………………………….…….............1 1.2. Statement of the Problem……………………………..…………………………….…................3 1.3. Objectives of the Study …………..………………………………………..…………….….........7 1.3.1. General Objective……………………………………………………………..…….........7 -

Determinants of Rural Household's Livelihood Strategies in Machakel Woreda, East Gojjam Zone, Amhara Nation Regional State, Ethiopia

Developing Country Studies www.iiste.org ISSN 2224-607X (Paper) ISSN 2225-0565 (Online) Vol.8, No.10, 2018 Determinants of Rural Household's Livelihood Strategies in Machakel Woreda, East Gojjam Zone, Amhara Nation Regional State, Ethiopia Adey Belete Department of Disaster Risk Management & Sustainable Development, Institute of Disaster Risk Management & Food Security Studies, Bahir Dar University, P.O.Box 5501 Abstract Rural farm households face an increasing need of looking for alternative income sources to supplement their small scale agricultural activities. However, livelihood strategy is determined by complex and yet empirically untested factors in Machakel Woreda. Thus, the aim of this study was to assess the determinants of livelihood strategies in the study area. The data were obtained from 144 sample household heads that were selected through a combination of multi-stage sampling like purposive and simple random sampling techniques. Data were collected through key informant interview, focus group discussion and interview schedule. Multinomial logistic regression model used to analyze determinants of livelihood strategies. Data analysis revealed that farm alone activities has a leading contribution to the total income of sample households (69.8%) followed by non-farm activities (17.2%) and off- farm activities (13 %.). Crop production was the dominant livelihood in the study area and land fragmentation, decline in productivity, occurrence of disaster risk like crop and livestock disease, hail storm, flash flood etc. and market fluctuation were major threatens of livelihood. Four livelihood strategies namely farm alone, farm plus non-farm, farm plus off-farm and farm plus non-farm plus off-farm were identified. Age, education level, sex of household head, marital status, credit access, farm land size, livestock holding size , agro-ecology, family size, frequency of extension contact, distance from market and total net income were major determinants of livelihood strategies in the study area. -

Protecting Land Tenure Security of Women in Ethiopia: Evidence from the Land Investment for Transformation Program

PROTECTING LAND TENURE SECURITY OF WOMEN IN ETHIOPIA: EVIDENCE FROM THE LAND INVESTMENT FOR TRANSFORMATION PROGRAM Workwoha Mekonen, Ziade Hailu, John Leckie, and Gladys Savolainen Land Investment for Transformation Programme (LIFT) (DAI Global) This research paper was created with funding and technical support of the Research Consortium on Women’s Land Rights, an initiative of Resource Equity. The Research Consortium on Women’s Land Rights is a community of learning and practice that works to increase the quantity and strengthen the quality of research on interventions to advance women’s land and resource rights. Among other things, the Consortium commissions new research that promotes innovations in practice and addresses gaps in evidence on what works to improve women’s land rights. Learn more about the Research Consortium on Women’s Land Rights by visiting https://consortium.resourceequity.org/ This paper assesses the effectiveness of a specific land tenure intervention to improve the lives of women, by asking new questions of available project data sets. ABSTRACT The purpose of this research is to investigate threats to women’s land rights and explore the effectiveness of land certification interventions using evidence from the Land Investment for Transformation (LIFT) program in Ethiopia. More specifically, the study aims to provide evidence on the extent that LIFT contributed to women’s tenure security. The research used a mixed method approach that integrated quantitative and qualitative data. Quantitative information was analyzed from the profiles of more than seven million parcels to understand how the program had incorporated gender interests into the Second Level Land Certification (SLLC) process. -

Food Insecurity Among Households with and Without Podoconiosis in East and West Gojjam, Ethiopia

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Sussex Research Online Food insecurity among households with and without podoconiosis in East and West Gojjam, Ethiopia Article (Published Version) Ketema, Kassahun, Tsegay, Girmay, Gedle, Dereje, Davey, Gail and Deribe, Kebede (2018) Food insecurity among households with and without podoconiosis in East and West Gojjam, Ethiopia. EC Nutrition, 13 (7). pp. 414-423. ISSN 2453-188X This version is available from Sussex Research Online: http://sro.sussex.ac.uk/id/eprint/76681/ This document is made available in accordance with publisher policies and may differ from the published version or from the version of record. If you wish to cite this item you are advised to consult the publisher’s version. Please see the URL above for details on accessing the published version. Copyright and reuse: Sussex Research Online is a digital repository of the research output of the University. Copyright and all moral rights to the version of the paper presented here belong to the individual author(s) and/or other copyright owners. To the extent reasonable and practicable, the material made available in SRO has been checked for eligibility before being made available. Copies of full text items generally can be reproduced, displayed or performed and given to third parties in any format or medium for personal research or study, educational, or not-for-profit purposes without prior permission or charge, provided that the authors, title and full bibliographic details are credited, a hyperlink and/or URL is given for the original metadata page and the content is not changed in any way. -

Yes I Do. Ethiopia – Amhara Region

Yes I Do. Ethiopia – Amhara Region The situation of child marriage in Qewet and Bahir Dar Zurida: a focus on gender roles, parenting and young people’s future perspectives Abeje Berhanu Dereje Tesama Beleyne Worku Almaz Mekonnen Lisa Juanola Anke van der Kwaak University of Addis Ababa & Royal Tropical Institute January 2019 1 Contents Abbreviations ................................................................................................................................................ 3 1. Introduction .......................................................................................................................................... 4 1.1 Background of the Yes I Do programme .............................................................................................. 4 1.2 Process of identifying themes for this study ....................................................................................... 4 1.3 Social and gender norms related to child marrige .............................................................................. 5 1.4 Objective of the study ......................................................................................................................... 7 2. Methodology ......................................................................................................................................... 9 2.1 Description of the study areas ............................................................................................................. 9 2.1.1 Qewet woreda, North Shewa zone.............................................................................................. -

Dairy Value Chain in West Amhara (Bahir Dar Zuria and Fogera Woreda Case)

Dairy Value Chain in West Amhara (Bahir Dar Zuria and Fogera Woreda case) Paulos Desalegn Commissioned by Programme for Agro-Business Induced Growth in the Amhara National Regional State August, 2018 Bahir Dar, Ethiopia 0 | Page List of Abbreviations and Acronyms AACCSA - Addis Ababa Chamber of Commerce and Sectorial Association AGP - Agriculture Growth Program AgroBIG – Agro-Business Induced Growth program AI - Artificial Insemination BZW - Bahir Dar Zuria Woreda CAADP - Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program CIF - Cost, Insurance and Freight CSA - Central Statistics Agency ETB - Ethiopian Birr EU - European Union FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FEED - Feed Enhancement for Ethiopian Development FGD - Focal Group Discussion FSP - Food Security Program FTC - Farmers Training Center GTP II - Second Growth and Transformation Plan KI - Key Informants KM (km) - Kilo Meter LIVES - Livestock and Irrigation Value chains for Ethiopian Smallholders LMD - Livestock Market Development LMP - Livestock Master Plan Ltr (ltr) - Liter PIF - Policy and Investment Framework USD - United States Dollar 1 | Page Table of Contents List of Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................... 1 Executive summary ....................................................................................................... 3 List of Tables ............................................................................................................... 4 List of Figures -

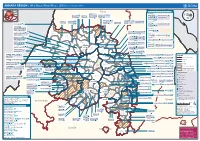

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

Farmers' Varietal Selection of Food Barley Genotypes in Gozamin

American-Eurasian J. Agric. & Environ. Sci., 17 (3): 232-238, 2017 ISSN 1818-6769 © IDOSI Publications, 2017 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.aejaes.2017.232.238 Farmers’ Varietal Selection of Food Barley Genotypes in Gozamin District of East Gojjam Zone, Northwestern Ethiopia Yalemtesfa Firew Guade Department of Horticulture, College of Agriculture and Natural Resources, Debre Markos University, Ethiopia Abstract: In this study, the performance of four improved food barley varieties obtained from Holleta Agricultural Research Center and local variety collected from the study area were evaluated in randomized complete block design (RCBD) with three replications under farmers’ participatory selection scheme during 2016 main cropping season in Gozamin district, East Gojjam Zone, Northwestern Ethiopia. The objectives of this study were to select adaptable and high yielding food barley genotype(s) using farmers’ preferences and to identify farmers’ preference and selection criteria of the study area. Farmers’ set; grain yield, early maturity, tillering ability and spike length as their selection criteria at maturity stage of the crop. The results of analysis of variance (ANOVA) indicated significant differences among genotypes for all traits tested except number of effective tillers and thousand seed weight which were non-significant at 5% probability level. The improved variety EH-1493 (133 days) was the earliest while local variety (142 days) was the latest. The highest mean grain yield was obtained from HB-1307 (3700 kg ha-1 ) and Cross-41/98 (3133 kg ha-1 ) whereas the lowest from the local variety (1693 kg ha 11). Similarly, HB-1307(5033 kg ha ) and Cross-41/98 (3633.33 kg ha 1) had given comparatively the highest above ground biomass yield which was used as a source of feed for animals. -

Addis Ababa University College of Development Studies Tourism Development and Managment Programme

ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES TOURISM DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGMENT PROGRAMME Assess Tourism Resources and Its Development Challenges in Sekela Wereda, West Gojjam, Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia Submitted by: Mekuanent Ayalew Kassa A Thesis Submitted to the College of Development Studies of Addis Ababa University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Tourism Development and Management Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa, Ethiopia June, 2019 1 ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES TOURISM DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGMENT PROGRAMME Assess Tourism Resources and Its Development Challenges in Sekela Wereda, West Gojjam, Amhara National Regional State, Ethiopia Submitted by: Mekuanent Ayalew Kassa A Thesis Submitted to the College of Development Studies of Addis Ababa University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts in Tourism Development and Management Addis Ababa University Addis Ababa, Ethiopia June, 2019 2 ADDIS ABABA UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF DEVELOPMENT STUDIES TOURISM DEVELOPMENT AND MANAGMENT PROGRAMME This is to certify that the thesis prepared by Mekuanent Ayalew Kassa, entitled: "Assess Tourism Resources and Its Development Opportunities and Challenges in Sekela Wereda". In partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Art in Tourism Development and Management complies with the regulations of the University and meets the accepted standards with respect to originality and quality. Signed by Examining