The Role of Users at the Different Levels of Wash Projects

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Feasibility Study for a Lake Tana Biosphere Reserve, Ethiopia

Friedrich zur Heide Feasibility Study for a Lake Tana Biosphere Reserve, Ethiopia BfN-Skripten 317 2012 Feasibility Study for a Lake Tana Biosphere Reserve, Ethiopia Friedrich zur Heide Cover pictures: Tributary of the Blue Nile River near the Nile falls (top left); fisher in his traditional Papyrus boat (Tanqua) at the southwestern papyrus belt of Lake Tana (top centre); flooded shores of Deq Island (top right); wild coffee on Zege Peninsula (bottom left); field with Guizotia scabra in the Chimba wetland (bottom centre) and Nymphaea nouchali var. caerulea (bottom right) (F. zur Heide). Author’s address: Friedrich zur Heide Michael Succow Foundation Ellernholzstrasse 1/3 D-17489 Greifswald, Germany Phone: +49 3834 83 542-15 Fax: +49 3834 83 542-22 Email: [email protected] Co-authors/support: Dr. Lutz Fähser Michael Succow Foundation Renée Moreaux Institute of Botany and Landscape Ecology, University of Greifswald Christian Sefrin Department of Geography, University of Bonn Maxi Springsguth Institute of Botany and Landscape Ecology, University of Greifswald Fanny Mundt Institute of Botany and Landscape Ecology, University of Greifswald Scientific Supervisor: Prof. Dr. Michael Succow Michael Succow Foundation Email: [email protected] Technical Supervisor at BfN: Florian Carius Division I 2.3 “International Nature Conservation” Email: [email protected] The study was conducted by the Michael Succow Foundation (MSF) in cooperation with the Amhara National Regional State Bureau of Culture, Tourism and Parks Development (BoCTPD) and supported by the German Federal Agency for Nature Conservation (BfN) with funds from the Environmental Research Plan (FKZ: 3510 82 3900) of the German Federal Ministry for the Environment, Nature Conservation and Nuclear Safety (BMU). -

Dairy Value Chain in West Amhara (Bahir Dar Zuria and Fogera Woreda Case)

Dairy Value Chain in West Amhara (Bahir Dar Zuria and Fogera Woreda case) Paulos Desalegn Commissioned by Programme for Agro-Business Induced Growth in the Amhara National Regional State August, 2018 Bahir Dar, Ethiopia 0 | Page List of Abbreviations and Acronyms AACCSA - Addis Ababa Chamber of Commerce and Sectorial Association AGP - Agriculture Growth Program AgroBIG – Agro-Business Induced Growth program AI - Artificial Insemination BZW - Bahir Dar Zuria Woreda CAADP - Comprehensive Africa Agriculture Development Program CIF - Cost, Insurance and Freight CSA - Central Statistics Agency ETB - Ethiopian Birr EU - European Union FAO - Food and Agriculture Organization of the United Nations FEED - Feed Enhancement for Ethiopian Development FGD - Focal Group Discussion FSP - Food Security Program FTC - Farmers Training Center GTP II - Second Growth and Transformation Plan KI - Key Informants KM (km) - Kilo Meter LIVES - Livestock and Irrigation Value chains for Ethiopian Smallholders LMD - Livestock Market Development LMP - Livestock Master Plan Ltr (ltr) - Liter PIF - Policy and Investment Framework USD - United States Dollar 1 | Page Table of Contents List of Abbreviations and Acronyms .................................................................................... 1 Executive summary ....................................................................................................... 3 List of Tables ............................................................................................................... 4 List of Figures -

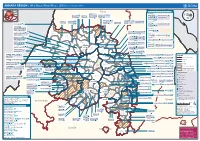

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (As of 13 February 2013)

AMHARA REGION : Who Does What Where (3W) (as of 13 February 2013) Tigray Tigray Interventions/Projects at Woreda Level Afar Amhara ERCS: Lay Gayint: Beneshangul Gumu / Dire Dawa Plan Int.: Addis Ababa Hareri Save the fk Save the Save the df d/k/ CARE:f k Save the Children:f Gambela Save the Oromia Children: Children:f Children: Somali FHI: Welthungerhilfe: SNNPR j j Children:l lf/k / Oxfam GB:af ACF: ACF: Save the Save the af/k af/k Save the df Save the Save the Tach Gayint: Children:f Children: Children:fj Children:l Children: l FHI:l/k MSF Holand:f/ ! kj CARE: k Save the Children:f ! FHI:lf/k Oxfam GB: a Tselemt Save the Childrenf: j Addi Dessie Zuria: WVE: Arekay dlfk Tsegede ! Beyeda Concern:î l/ Mirab ! Concern:/ Welthungerhilfe:k Save the Children: Armacho f/k Debark Save the Children:fj Kelela: Welthungerhilfe: ! / Tach Abergele CRS: ak Save the Children:fj ! Armacho ! FHI: Save the l/k Save thef Dabat Janamora Legambo: Children:dfkj Children: ! Plan Int.:d/ j WVE: Concern: GOAL: Save the Children: dlfk Sahla k/ a / f ! ! Save the ! Lay Metema North Ziquala Children:fkj Armacho Wegera ACF: Save the Children: Tenta: ! k f Gonder ! Wag WVE: Plan Int.: / Concern: Save the dlfk Himra d k/ a WVE: ! Children: f Sekota GOAL: dlf Save the Children: Concern: Save the / ! Save: f/k Chilga ! a/ j East Children:f West ! Belesa FHI:l Save the Children:/ /k ! Gonder Belesa Dehana ! CRS: Welthungerhilfe:/ Dembia Zuria ! î Save thedf Gaz GOAL: Children: Quara ! / j CARE: WVE: Gibla ! l ! Save the Children: Welthungerhilfe: k d k/ Takusa dlfj k -

Rabies: Knowledge, Attitude and Practices in and Around South Gondar, North West Ethiopia

diseases Article Rabies: Knowledge, Attitude and Practices in and Around South Gondar, North West Ethiopia Amare Bihon 1,* , Desalegn Meresa 2 and Abraham Tesfaw 3 1 School of Veterinary Medicine, Woldia University, Woldia 7220, Ethiopia 2 College of Health Science, Mekele University, Mekele 7000, Ethiopia; [email protected] 3 College of Veterinary Medicine, Samara University, Samara 7240, Ethiopia; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] or [email protected]; Tel.: +251-(0)9-4514-3238 Received: 24 December 2019; Accepted: 6 February 2020; Published: 24 February 2020 Abstract: A cross-sectional study was conducted from February 2017 to April 2017 to assess knowledge, attitude and practices of the community towards rabies in south Gondar zone, Ethiopia. A structured closed ended questionnaire was used to collect the data through face to face interviews among 384 respondents. The data were then analyzed using SPSS statistical software version 20. Almost all (91.5%) surveyed individuals were aware of rabies. Bite was known as mode of rabies transmission by majority of the respondents (71.1%) with considerable means of transmission through wound contact with saliva of diseased animals. Sudden change of behavior was described as a major clinical sign of rabies in animals by the majority of the respondents. Nearly half of the respondents (48.2%) believed that consumption of rabid animal’s meat can be a medicine for human rabies and majority of the respondents (66.7%) indicated crossing a river before 40 days after dog bite increases severity of the disease. More than eighty percent of the respondents prefer traditional medicines for treating rabies in humans. -

English-Full (0.5

Enhancing the Role of Forestry in Building Climate Resilient Green Economy in Ethiopia Strategy for scaling up effective forest management practices in Amhara National Regional State with particular emphasis on smallholder plantations Wubalem Tadesse Alemu Gezahegne Teshome Tesema Bitew Shibabaw Berihun Tefera Habtemariam Kassa Center for International Forestry Research Ethiopia Office Addis Ababa October 2015 Copyright © Center for International Forestry Research, 2015 Cover photo by authors FOREWORD This regional strategy document for scaling up effective forest management practices in Amhara National Regional State, with particular emphasis on smallholder plantations, was produced as one of the outputs of a project entitled “Enhancing the Role of Forestry in Ethiopia’s Climate Resilient Green Economy”, and implemented between September 2013 and August 2015. CIFOR and our ministry actively collaborated in the planning and implementation of the project, which involved over 25 senior experts drawn from Federal ministries, regional bureaus, Federal and regional research institutes, and from Wondo Genet College of Forestry and Natural Resources and other universities. The senior experts were organised into five teams, which set out to identify effective forest management practices, and enabling conditions for scaling them up, with the aim of significantly enhancing the role of forests in building a climate resilient green economy in Ethiopia. The five forest management practices studied were: the establishment and management of area exclosures; the management of plantation forests; Participatory Forest Management (PFM); agroforestry (AF); and the management of dry forests and woodlands. Each team focused on only one of the five forest management practices, and concentrated its study in one regional state. -

Ethiopia: Amhara Region Administrative Map (As of 05 Jan 2015)

Ethiopia: Amhara region administrative map (as of 05 Jan 2015) ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! Abrha jara ! Tselemt !Adi Arikay Town ! Addi Arekay ! Zarima Town !Kerakr ! ! T!IGRAY Tsegede ! ! Mirab Armacho Beyeda ! Debark ! Debarq Town ! Dil Yibza Town ! ! Weken Town Abergele Tach Armacho ! Sanja Town Mekane Berhan Town ! Dabat DabatTown ! Metema Town ! Janamora ! Masero Denb Town ! Sahla ! Kokit Town Gedebge Town SUDAN ! ! Wegera ! Genda Wuha Town Ziquala ! Amba Giorges Town Tsitsika Town ! ! ! ! Metema Lay ArmachoTikil Dingay Town ! Wag Himra North Gonder ! Sekota Sekota ! Shinfa Tomn Negade Bahr ! ! Gondar Chilga Aukel Ketema ! ! Ayimba Town East Belesa Seraba ! Hamusit ! ! West Belesa ! ! ARIBAYA TOWN Gonder Zuria ! Koladiba Town AMED WERK TOWN ! Dehana ! Dagoma ! Dembia Maksegnit ! Gwehala ! ! Chuahit Town ! ! ! Salya Town Gaz Gibla ! Infranz Gorgora Town ! ! Quara Gelegu Town Takusa Dalga Town ! ! Ebenat Kobo Town Adis Zemen Town Bugna ! ! ! Ambo Meda TownEbinat ! ! Yafiga Town Kobo ! Gidan Libo Kemkem ! Esey Debr Lake Tana Lalibela Town Gomenge ! Lasta ! Muja Town Robit ! ! ! Dengel Ber Gobye Town Shahura ! ! ! Wereta Town Kulmesk Town Alfa ! Amedber Town ! ! KUNIZILA TOWN ! Debre Tabor North Wollo ! Hara Town Fogera Lay Gayint Weldiya ! Farta ! Gasay! Town Meket ! Hamusit Ketrma ! ! Filahit Town Guba Lafto ! AFAR South Gonder Sal!i Town Nefas mewicha Town ! ! Fendiqa Town Zege Town Anibesema Jawi ! ! ! MersaTown Semen Achefer ! Arib Gebeya YISMALA TOWN ! Este Town Arb Gegeya Town Kon Town ! ! ! ! Wegel tena Town Habru ! Fendka Town Dera -

ASSESSMENT of CHALLENGES of SUSTAINABLE RURAL WATER SUPPLY: QUARIT WOREDA, AMHARA REGION a Project Paper Presented to the Facult

ASSESSMENT OF CHALLENGES OF SUSTAINABLE RURAL WATER SUPPLY: QUARIT WOREDA, AMHARA REGION A Project Paper Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School Of Cornell University In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Professional Studies by Zemenu Awoke January 2012 © 2012 Zemenu Awoke Alemeyehu ABSTRACT Sustainability of water supplies is a key challenge, both in terms of water resources and service delivery. The United Nations International Children’s Fund (UNICEF) estimates that one third of rural water supplies in sub-Saharan Africa are non- operational at any given time. Consequently, the objective of this study is to identify the main challenges to sustainable rural water supply systems by evaluating and comparing functional and non-functional systems. The study was carried out in Quarit Woreda located in West Gojjam, Amhara Region, Ethiopia. A total of 217 water supply points (169 hand-dug wells and 50 natural protected springs) were constructed in the years 2005 to 2009. Of these water points, 184 were functional and 33 were non-functional. Twelve water supply systems (six functional and six non-functional) among these systems were selected. A household survey concerning the demand responsiveness of projects, water use practices, construction quality, financial management and their level of satisfaction was conducted at 180 households. All surveyed water projects were initiated by the community and the almost all of the potential users contributed money and labor towards the construction of the water supply point. One of the main differences between the functional and non-functional system was the involvement of the local leaders. -

Inter Personal Conflict Resolution Methods on Case of Land in Semadawerda, South Gonder Ethiopia

ial Scien oc ce S s Bantihun and Worku, Arts Social Sci J 2017, 8:6 d J n o u a r DOI: 10.4172/2151-6200.1000315 s n t a r l A Arts and Social Sciences Journal ISSN: 2151-6200 Research Article Open Access Inter Personal Conflict Resolution Methods on Case of Land in SemadaWerda, South Gonder Ethiopia Abay Bantihun* and Melese Worku Faculty of Agriculture and Environmental Sciences, Debre Markos University, Deber Tabor, Ethiopia Abstract The study is about traditional interpersonal conflict resolution methods in the case of land in Arga and Asherakebele 16 in Simada Worda in the local community conflict resolution system was seen in this research study. Simadaworda Arga and Asherakebele the respondents of this research activity, from the total household 75 was selected, from those household 45 males and 30 females was selected based on sampling point. From sampling fighter 25 was selected, from those male 17 female 8, official experts was 24, from those 16 male and 8 female. From total respondent were selected 124, from those 78 males and 46 female. Most of the respondents result indicated that conflict arising by using inheritance problems from males 24.3% (19) and females 19.56% % (9), then problem related to boundary conflicts 34.6% (27 male and 16 female). Keywords: Simada Worda; Arga; Ashera; Inheritance; and investment in natural resources management [4], it is gaining Incompatibility; Traditional; Transparency traction in international development circles DFID [5], as well as in the environmental conservation and peace building communities [6,7]. Background of the Study Simadaworda one of the south Gondar zones, especially this worda Conflict is fundamental and predictable part of human existence. -

D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 1

D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 1. Tigrey No. Woredas Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Expected Connecting Point 1 Adwa 13 Per Filed Survey by ETC 2(*) Hawzen 12 3(*) Wukro 7 Per Feasibility Study 4(*) Samre 13 Per Filed Survey by ETC 5 Alamata 10 Total 55 1 Tahtay Adiyabo 8 2 Medebay Zana 10 3 Laelay Mayechew 10 4 Kola Temben 11 5 Abergele 7 Per Filed Survey by ETC 6 Ganta Afeshum 15 7 Atsbi Wenberta 9 8 Enderta 14 9(*) Hintalo Wajirat 16 10 Ofla 15 Total 115 1 Kafta Humer 5 2 Laelay Adiyabo 8 3 Tahtay Koraro 8 4 Asegede Tsimbela 10 5 Tselemti 7 6(**) Welkait 7 7(**) Tsegede 6 8 Mereb Lehe 10 9(*) Enticho 21 10(**) Werie Lehe 16 Per Filed Survey by ETC 11 Tahtay Maychew 8 12(*)(**) Naeder Adet 9 13 Degua temben 9 14 Gulomahda 11 15 Erob 10 16 Saesi Tsaedaemba 14 17 Alage 13 18 Endmehoni 9 19(**) Rayaazebo 12 20 Ahferom 15 Total 208 1/14 Tigrey D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 2. Affar No. Woredas Phase 1 Phase 2 Phase 3 Expected Connecting Point 1 Ayisaita 3 2 Dubti 5 Per Filed Survey by ETC 3 Chifra 2 Total 10 1(*) Mile 1 2(*) Elidar 1 3 Koneba 4 4 Berahle 4 Per Filed Survey by ETC 5 Amibara 5 6 Gewane 1 7 Ewa 1 8 Dewele 1 Total 18 1 Ere Bti 1 2 Abala 2 3 Megale 1 4 Dalul 4 5 Afdera 1 6 Awash Fentale 3 7 Dulecha 1 8 Bure Mudaytu 1 Per Filed Survey by ETC 9 Arboba Special Woreda 1 10 Aura 1 11 Teru 1 12 Yalo 1 13 Gulina 1 14 Telalak 1 15 Simurobi 1 Total 21 2/14 Affar D.Table 9.5-1 Number of PCO Planned 3. -

UCC Library and UCC Researchers Have Made This Item Openly Available. Please Let Us Know How This Has Helped You. Thanks! Downlo

UCC Library and UCC researchers have made this item openly available. Please let us know how this has helped you. Thanks! Title Analysis of institutional arrangements and common pool resources governance: the case of Lake Tana sub-basin, Ethiopia Author(s) Ketema, Dessalegn Molla Publication date 2013 Original citation Ketema, D. M. 2013. Analysis of institutional arrangements and common pool resources governance: the case of Lake Tana sub-basin, Ethiopia. PhD Thesis, University College Cork. Type of publication Doctoral thesis Rights © 2013, Dessalegn M. Ketema http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/3.0/ Item downloaded http://hdl.handle.net/10468/1429 from Downloaded on 2021-10-06T09:30:28Z Analysis of Institutional Arrangements and Common Pool Resources Governance: The case of Lake Tana Sub-Basin, Ethiopia. A thesis Presented to The Department of Food Business and Development National University of Ireland, Cork. In Fulfillment of the Requirement for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy (PhD) By Dessalegn Molla Ketema (December, 2013) Head of Department: Professor Michal Ward (PhD) Research Supervisors: Nicholas G. Chisholm (PhD) Patrick Enright (PhD) Dedicated to My Mom Yelfign Derbew Wahel DECLARATION I, the undersigned, declare that the dissertation hereby submitted by me for the PhD Degree in Rural Development at the University College Cork (UCC) is my own independent work that, to the best of my knowledge and belief, has not previously been submitted by me or somebody else at another university. All sources of materials used for this dissertation have been duly acknowledged. Dessalegn M. Ketema Signature: _____________________________ Place: ________________________________ Date of Submission: _____________________ i ACKNOWLEDGEMENT First and foremost I want to praise almighty God-the Father, the Son and the Holy Spirit, for his love, care, compassion and forgiveness. -

Prevalence of Small Ruminant Lung Worm Infection in Yilmana Densa District Northwest Ethiopia

Middle-East Journal of Scientific Research 27 (7): 538-543, 2019 ISSN 1990-9233 © IDOSI Publications, 2019 DOI: 10.5829/idosi.mejsr.2019.538.543 Prevalence of Small Ruminant Lung Worm Infection in Yilmana Densa District Northwest Ethiopia Fentahun Mengie, Tsegaw Fentie and Abiyu Muluken College of Veterinary Medicine, Gondar University, Gondar, Ethiopia Abstract: A cross-sectional study was conducted from November 2017 to March 2018 to estimate the prevalence of lungworms infection and to investigate possible risk factors associated with small ruminant lungworm infections in Yilmana densa district of Amahara region, Ethiopia. Fecal samples were collected from randomly selected 384 animals (242 sheep and 142 goats) to examine first stage larvae L (1) using modified Baerman technique. The overall prevalence of lungworm infections in the study area was 53.13% (95%CI: 48.11-58.13%) in coproscopic examination. Prevalence of lungworm infection was significantly higher in goats (59.86%) than in sheep (49.17%). Three species of lungworms were identified with higher proportion of infection with Dictyocaulus filaria (62.75%) and Mulliries capillaries (23.5%). Univariable and multivariable logistic regression analyses indicated that host related factors such as animal age, sex, body condition, respiratory illness and management were identified as potential risk factors for the occurrence of lungworms infection in small ruminants in the study area. Female animals were more likely of getting lungworm infection (OR= 2.056; p=0.001) as compared to male animals. Young age (OR=1.69; p=0.012), poor conditioned animals (OR=24.42; p=<0.001) and animals with respiratory illness were at higher risk of getting lungworm infections. -

Ethiopia, Amhara Region Infectious Disease Surveillance (Amrids) Project Completion Report

Ethiopia Amhara National Regional State Health Bureau Ethiopia, Amhara Region Infectious Disease Surveillance (AmRids) Project Completion Report February 2015 Japan International Cooperation Agency Japan Anti-Tuberculosis Association 㻭㼎㼎㼞㼑㼢㼕㼍㼠㼕㼛㼚㼟㻌 AFP Acute flaccid paralysis ARHB Amhara National Regional State Health Bureau CDC Centers for Disease Control and Prevention EPHI Ethiopia Public Health Institute EPI Expanded Programme on Immunization FETP Field Epidemiologist Training Programme FMoH Federal Ministry of Health HC Health Centre HDA Health Development Army HEP Health Extension Programme HEW Health Extension Worker HP Health Post IDSR Integrated Disease Surveillance and Response IHR International Health Regulation JCC Joint Coordination Committee JICA Japan International Cooperation Agency KSO Kebele Surveillance Officer NNT Neonatal Tetanus PHEM Public Health Emergency Management SNNPR Southern Nations, Nationalities, and Peoples' Region SOP Standard Operating Procedures TOT Training of Trainers WHO World Health Organisation Federal Democratic Republic of Ethiopia JICA Amhara Regional Infectious Disease Surveillance (AmRids) Project Completion Report February 2015 Contents 1㸬Background of the Project .......................................................................................... 1 2㸬Project Activity .......................................................................................................... 4 2.1 Strengthening surveillance system .........................................................................