From Jasmine to Jihad

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ansar Al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST)

Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST) Name: Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST) Type of Organization: Insurgent non-state actor religious social services provider terrorist transnational violent Ideologies and Affiliations: ISIS–affiliated group Islamist jihadist Qutbist Salafist Sunni takfiri Place of Origin: Tunisia Year of Origin: 2011 Founder(s): Seifallah Ben Hassine Places of Operation: Tunisia Overview Also Known As: Al-Qayrawan Media Foundation1 Partisans of Sharia in Tunisia7 Ansar al-Sharia2 Shabab al-Tawhid (ST)8 Ansar al-Shari’ah3 Supporters of Islamic Law9 Ansar al-Shari’a in Tunisia (AAS-T)4 Supporters of Islamic Law in Tunisia10 Ansar al-Shari’ah in Tunisia5 Supporters of Sharia in Tunisia11 Partisans of Islamic Law in Tunisia6 Executive Summary: Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST) was a Salafist group that was prominent in Tunisia from 2011 to 2013.12 AST sought to implement sharia (Islamic law) in the country and used violence in furtherance of that goal under the banner of hisbah (the duty to command moral acts and prohibit immoral ones).13 AST also actively engaged in dawa (Islamic missionary work), which took on many forms but were largely centered upon Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST) the provision of public services.14 Accordingly, AST found a receptive audience among Tunisians frustrated with the political instability and dire economic conditions that followed the 2011 Tunisian Revolution.15 The group received logistical support from al-Qaeda central, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Ansar al-Sharia in Libya (ASL), and later, from ISIS.16 AST was designated as a terrorist group by the United States, the United Nations, and Tunisia, among others.17 AST was originally conceived in a Tunisian prison by 20 Islamist inmates in 2006, according to Aaron Zelin at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. -

The Al Qaeda Network a New Framework for Defining the Enemy

THE AL QAEDA NETWORK A NEW FRAMEWORK FOR DEFINING THE ENEMY KATHERINE ZIMMERMAN SEPTEMBER 2013 THE AL QAEDA NETWORK A NEW FRAMEWORK FOR DEFINING THE ENEMY KATHERINE ZIMMERMAN SEPTEMBER 2013 A REPORT BY AEI’S CRITICAL THREATS PROJECT ABOUT US About the Author Katherine Zimmerman is a senior analyst and the al Qaeda and Associated Movements Team Lead for the Ameri- can Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project. Her work has focused on al Qaeda’s affiliates in the Gulf of Aden region and associated movements in western and northern Africa. She specializes in the Yemen-based group, al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and al Qaeda’s affiliate in Somalia, al Shabaab. Zimmerman has testified in front of Congress and briefed Members and congressional staff, as well as members of the defense community. She has written analyses of U.S. national security interests related to the threat from the al Qaeda network for the Weekly Standard, National Review Online, and the Huffington Post, among others. Acknowledgments The ideas presented in this paper have been developed and refined over the course of many conversations with the research teams at the Institute for the Study of War and the American Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project. The valuable insights and understandings of regional groups provided by these teams directly contributed to the final product, and I am very grateful to them for sharing their expertise with me. I would also like to express my deep gratitude to Dr. Kimberly Kagan and Jessica Lewis for dedicating their time to helping refine my intellectual under- standing of networks and to Danielle Pletka, whose full support and effort helped shape the final product. -

The Tunisian-Libyan Jihadi Connection | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds The Tunisian-Libyan Jihadi Connection by Aaron Y. Zelin Jul 6, 2015 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Aaron Y. Zelin Aaron Y. Zelin is the Richard Borow Fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy where his research focuses on Sunni Arab jihadi groups in North Africa and Syria as well as the trend of foreign fighting and online jihadism. Articles & Testimony A relationship that dates back decades deserves closer attention, and could well lead to repeat Islamic State attacks on Tunisian soil. t should have come as no surprise that Seifeddine Rezgui, the individual who attacked tourists in Sousse, Tunisia, I more than a week ago, had trained at a camp in Libya. The attack represented the continuation of a relationship between Tunisian and Libyan militants that, having intensified since 2011, goes back to the 1980s. The events in Sousse are a stark reminder of this relationship: a connection that is set to continue should the Islamic State (IS) choose to repeat attacks in Tunisia in the coming months. Brief History on the Tunisian-Libyan Militant Nexus A lthough Ennahda did not explicitly call for individuals to fight against the Soviets during the Afghan jihad, militants in the mujahedeen were regularly involved in facilitation and logistical networks that brought Libyans to the region. Additionally, according to Noman Benotman, a former shura council member of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) in Afghanistan in the 1980s, Libyans alongside Abdul Rasul Sayyaf, the Afghan leader of Ittihad- e-Islami, attempted to help the Tunisians create their own military camp and organization. -

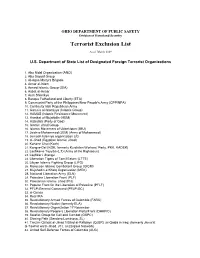

Terrorist Exclusion List

OHIO DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY Division of Homeland Security Terrorist Exclusion List As of March 2009 U.S. Department of State List of Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations 1. Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) 2. Abu Sayyaf Group 3. Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade 4. Ansar al-Islam 5. Armed Islamic Group (GIA) 6. Asbat al-Ansar 7. Aum Shinrikyo 8. Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) 9. Communist Party of the Philippines/New People's Army (CPP/NPA) 10. Continuity Irish Republican Army 11. Gama’a al-Islamiyya (Islamic Group) 12. HAMAS (Islamic Resistance Movement) 13. Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM) 14. Hizballah (Party of God) 15. Islamic Jihad Group 16. Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) 17. Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM) (Army of Mohammed) 18. Jemaah Islamiya organization (JI) 19. al-Jihad (Egyptian Islamic Jihad) 20. Kahane Chai (Kach) 21. Kongra-Gel (KGK, formerly Kurdistan Workers' Party, PKK, KADEK) 22. Lashkar-e Tayyiba (LT) (Army of the Righteous) 23. Lashkar i Jhangvi 24. Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) 25. Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) 26. Moroccan Islamic Combatant Group (GICM) 27. Mujahedin-e Khalq Organization (MEK) 28. National Liberation Army (ELN) 29. Palestine Liberation Front (PLF) 30. Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) 31. Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLF) 32. PFLP-General Command (PFLP-GC) 33. al-Qa’ida 34. Real IRA 35. Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) 36. Revolutionary Nuclei (formerly ELA) 37. Revolutionary Organization 17 November 38. Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front (DHKP/C) 39. Salafist Group for Call and Combat (GSPC) 40. Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso, SL) 41. -

4. TUNISIA: CONFRONTING EXTREMISM Haim Malka1

4. TUNISIA: CONFRONTING EXTREMISM Haim Malka1 ihadi-salafi groups thrived in Tunisia after the government Jof Zine El-Abidine Ben Ali fell in January 2011. They swiftly took advantage of political uncertainty, ideological freedom, and porous borders to expand both their capabilities and area of operations. By the end of 2012 two strains of jihadi-salafism had emerged in the country. The first, which grew directly out of the revolutionary fervor and political openings of the Arab uprisings, prioritized and promoted religious outreach to mainstream audiences, often through social activism.2 Ansar al Shari‘a in Tunisia was the largest and most organized group taking this approach. The second strain followed al Qaeda’s tra- ditional method, with organized bands of underground fighters who emerged periodically to launch violent attacks against secu- rity forces and the government. This strain was represented by Tunisian jihadi-salafists calling themselves the Okba ibn Nafaa Brigade who established a base in Tunisia’s Chaambi Mountains 1. Sections of this chapter are drawn from two previously published papers: Haim Malka and William Lawrence, “Jihadi-Salafism’s Next Generation,” Center for Stra- tegic and International Studies, October 2013, http://csis.org/publication/jihadi- salafisms-next-generation; and Haim Malka, “The Struggle for Religious Identity in Tunisia and the Maghreb,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, May 2014, http://csis.org/publication/struggle-religious-identity-tunisia-and-maghreb. 2. For a detailed analysis of hybrid jihadi-salafism and efforts to combine extrem- ist ideology with social and political activism, see Malka and Lawrence, “Jihadi- Salafism’s Next Generation.” 92 Religious Radicalism after the Arab Uprisings 93 on the Tunisian-Algerian border and launched numerous at- tacks against security forces.3 The first model was primarily a political threat, while the second represented a security threat. -

Terrorist Exclusion List

OHIO DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY Division of Homeland Security Terrorist Exclusion List As of July 20, 2006 U.S. Department of State List of Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations 1. Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) 2. Abu Sayyaf Group 3. Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade 4. Ansar al-Islam 5. Armed Islamic Group (GIA) 6. Asbat al-Ansar 7. Aum Shinrikyo 8. Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) 9. Communist Party of the Philippines/New People's Army (CPP/NPA) 10. Continuity Irish Republican Army 11. Gama’a al-Islamiyya (Islamic Group) 12. HAMAS (Islamic Resistance Movement) 13. Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM) 14. Hizballah (Party of God) 15. Islamic Jihad Group 16. Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) 17. Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM) (Army of Mohammed) 18. Jemaah Islamiya organization (JI) 19. al-Jihad (Egyptian Islamic Jihad) 20. Kahane Chai (Kach) 21. Kongra-Gel (KGK, formerly Kurdistan Workers' Party, PKK, KADEK) 22. Lashkar-e Tayyiba (LT) (Army of the Righteous) 23. Lashkar i Jhangvi 24. Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) 25. Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) 26. Moroccan Islamic Combatant Group (GICM) 27. Mujahedin-e Khalq Organization (MEK) 28. National Liberation Army (ELN) 29. Palestine Liberation Front (PLF) 30. Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) 31. Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLF) 32. PFLP-General Command (PFLP-GC) 33. al-Qa’ida 34. Real IRA 35. Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) 36. Revolutionary Nuclei (formerly ELA) 37. Revolutionary Organization 17 November 38. Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front (DHKP/C) 39. Salafist Group for Call and Combat (GSPC) 40. Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso, SL) 41. -

The New Salafi Politics October 16, 2012 KHALIL MAZRAAWI/AFP/GETTYIMAGES KHALIL POMEPS Briefings 14 Contents

arab uprisings The New Salafi Politics October 16, 2012 KHALIL MAZRAAWI/AFP/GETTYIMAGES KHALIL POMEPS Briefings 14 Contents A New Salafi Politics . 6 The Salafi Moment . 8 The New Islamists . 10 Democracy, Salafi Style . 14 Who are Tunisia’s Salafis? . 16 Planting the seeds of Tunisia’s Ansar al Sharia . 20 Tunisia’s student Salafis . 22 Jihadists and Post-Jihadists in the Sinai . 25 The battle for al-Azhar . 28 Egypt’s ‘blessed’ Salafi votes . 30 Know your Ansar al-Sharia . 32 Osama bin Laden and the Saudi Muslim Brotherhood . 34 Lebanon’s Salafi Scare . 36 Islamism and the Syrian uprising . 38 The dangerous U .S . double standard on Islamist extremism . 48 The failure of #MuslimRage . 50 The Project on Middle East Political Science The Project on Middle East Political Science (POMEPS) is a collaborative network which aims to increase the impact of political scientists specializing in the study of the Middle East in the public sphere and in the academic community . POMEPS, directed by Marc Lynch, is based at the Institute for Middle East Studies at the George Washington University and is supported by the Carnegie Corporation and the Social Science Research Council . It is a co-sponsor of the Middle East Channel (http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com) . For more information, see http://www .pomeps .org . Online Article Index A new Salafi politics http://mideast .foreignpolicy .com/posts/2012/10/12/a_new_salafi_politics The Salafi Moment http://www .foreignpolicy .com/articles/2012/09/12/the_salafi_moment The New Islamists http://www .foreignpolicy -

Tunisia: in Brief

Tunisia: In Brief Updated March 16, 2020 Congressional Research Service https://crsreports.congress.gov RS21666 Tunisia: In Brief Summary As of March 15, 2020, Tunisia had initiated travel restrictions and other emergency measures in response to the COVID-19 pandemic, having reported at least 20 confirmed domestic cases. Tunisia remains the sole country to have made a durable transition to democracy as a result of the 2011 “Arab Spring.” An elected assembly adopted a new constitution in 2014 and Tunisians have since held two competitive national elections—most recently in late 2019—resulting in peaceful transfers of power. Tunisia has also taken steps toward empowering local-level government, with landmark local elections held in 2018. Yet the economy has suffered due to domestic, regional, and global factors, driving public dissatisfaction with political leaders. High unemployment and inflation, unpopular fiscal austerity measures, and concerns about corruption have spurred protests, labor unrest, and a backlash against mainstream politicians in recent years. Voters in the 2019 presidential and parliamentary elections largely rejected established parties and candidates in favor of independents and non-career politicians. The results unsettled Tunisia’s previous political alliances and may have implications for the future contours of its foreign relations and economic policies. Newly elected President Kais Saïed, who ran as an independent, is a constitutional scholar known for his socially conservative views and critique of Tunisia’s post-2011 political system. The self-described “Muslim democrat” party Al Nahda secured a slim plurality in parliament, but it has lost seats in each successive election since 2011. After protracted negotiations, a technocrat designated by President Saïed, Elyes Fakhfakh, secured parliamentary backing for a coalition government in late February 2020. -

Religious Radicalism After the Arab Uprisings JON B

Religious Religious Radicalism after the Arab Uprisings JON B. ALTERMAN, EDITOR Radicalism The Arab uprisings of 2011 created unexpected opportunities for religious radicals. Although many inside and outside the region initially saw the uprisings as liberal triumphs, illiberal forces have benefitted after the Arab disproportionately. In Tunisia, formally marginalized jihadi-salafi groups appealed for mainstream support, and in Egypt, the Muslim Brotherhood triumphed in Jon B. Alterman Uprisings elections. Even in Saudi Arabia, not known for either lively politics or for Jon B. Alterman political entrepreneurship, a surprising array of forces praised the rise of “Islamic democracy” under a Muslim Brotherhood banner. Yet, at the same time, the Arab uprisings reinforced regional governments’ advantages. The chaos engulfing parts of the region convinced some citizens that they were better off with the governments they had, and many governments successfully employed old and new tools of repression to reinforce the status quo. Religious Radicalism after the Arab Uprisings In the Middle East, conflicts that many thought were coming to an end Religious Radicalism after the Arab Uprisings will continue, as will the dynamism and innovation that have emerged among radical and opposition groups. To face the current threats, governments will need to use many of their existing tools skillfully, but they will also need to judge what tools will no longer work, and what new tools they have at their disposal. The stakes could not be higher. 1616 Rhode Island Avenue NW Washington, DC 20036 t. 202.887.0200 | f. 202.775.3199 www.csis.org EDITOR Jon B. Alterman Religious Radicalism after the Arab Uprisings Religious Radicalism after the Arab Uprisings Editor Jon B. -

Political Transition in Tunisia

Political Transition in Tunisia Alexis Arieff Analyst in African Affairs Carla E. Humud Analyst in Middle Eastern and African Affairs February 10, 2015 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RS21666 Political Transition in Tunisia Summary Tunisia has taken key steps toward democracy since the “Jasmine Revolution” in 2011, and has so far avoided the violent chaos and/or authoritarian resurrection seen in other “Arab Spring” countries. Tunisians adopted a new constitution in January 2014 and held national elections between October and December 2014, marking the completion of a four-year transitional period. A secularist party, Nidaa Tounes (“Tunisia’s Call”), won a plurality of seats in parliament, and its leader Béji Caïd Essebsi was elected president. The results reflect a decline in influence for the country’s main Islamist party, Al Nahda (alt: Ennahda, “Awakening” or “Renaissance”), which stepped down from leading the government in early 2014. Al Nahda, which did not run a presidential candidate, nevertheless demonstrated continuing electoral appeal, winning the second-largest block of legislative seats and joining a Nidaa Tounes-led coalition government. Although many Tunisians are proud of the country’s progress since 2011, public opinion polls also show anxiety over the country’s future. Tangible improvements in the economy or government service-delivery are few, while security threats have risen. Nidaa Tounes leaders have pledged to improve counterterrorism efforts and boost economic growth, but have not provided many concrete details on how they will pursue these ends. The party may struggle to achieve internal consensus on specific policies, as it was forged from disparate groups united largely in their opposition to Islamism. -

Ansar Al-Sharia Tunisia's Long Game

Ansar al-Sharia Tunisia’s Long Game: Dawa, Hisba, and Jihad Daveed Gartenstein-Ross ICCT Research Paper May 2013 In May 2013, the most significant clashes since the fall of Zine El Abidine Ben Ali occurred between the Tunisian government and the country’s largest salafi jihadist organisation – Ansar al-Sharia Tunisia (AST). ICCT Visiting Fellow Daveed Gartenstein-Ross argues that AST’s future in the country is highly uncertain. Combining a research visit to Tunisia with more traditional research, Daveed Gartenstein-Ross analyses AST’s current strategy and potential future transition from missionary work to jihad. He takes into consideration the group’s leadership, outlook, structure, size, and international connections. Concluding, he provides recommendations for engagement in Tunisia and the prevention of a long-term security problem connected to AST. About the Author Daveed Gartenstein-Ross is a visiting research fellow at the International Centre for Counter-Terrorism (ICCT) – The Hague, and a senior fellow at the Foundation for Defense of Democracies in Washington, D.C. While at ICCT, he is working on a major project that will examine the security implications of the Arab Uprisings, with a focus on Tunisia. The project will explore the strength of transnational jihadist networks in the wake of regional revolutions, the salafi jihadist strategy for exploiting developments, the influence of economic and ecological factors, and the likely impact of counterterrorism strategies forged by regional governments. Gartenstein-Ross's academic and professional focus is on the impact of violent non-state actors on twenty-first century conflict. Studies that Gartenstein-Ross has authored examine the economic aspects of al Qaeda’s military strategy; the radicalization process for jihadist terrorists; and theaters of conflict of particular relevance to the fight against al Qaeda. -

How the Islamic State Rose, Fell and Could Rise Again in the Maghreb

How the Islamic State Rose, Fell and Could Rise Again in the Maghreb 0LGGOH(DVWDQG1RUWK$IULFD5HSRUW1 _ -XO\ +HDGTXDUWHUV ,QWHUQDWLRQDO&ULVLV*URXS $YHQXH/RXLVH %UXVVHOV%HOJLXP 7HO )D[ EUXVVHOV#FULVLVJURXSRUJ Preventing War. Shaping Peace. Table of Contents Executive Summary ................................................................................................................... i I. Introduction ..................................................................................................................... 1 II. Maghrebi Foreign Fighters in ISIS ................................................................................... 2 A. Putting a Number on Maghrebi Foreign Fighters ..................................................... 2 B. Push and Pull Factors for Foreign Fighters ............................................................... 4 1. A market for revolutionary radicalism? ............................................................... 4 2. Security vacuums and favourable political contexts ............................................ 5 3. Pre-existing networks and locales of radicalism .................................................. 7 III. ISIS Targets the Maghreb ................................................................................................. 11 A. Libya: the Beachhead ................................................................................................. 11 1. Derna and Benghazi ............................................................................................. 12