4. TUNISIA: CONFRONTING EXTREMISM Haim Malka1

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances

SWP Research Paper Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber (Eds.) Jihadism in Africa Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances RP 5 June 2015 Berlin All rights reserved. © Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik, 2015 SWP Research Papers are peer reviewed by senior researchers and the execu- tive board of the Institute. They express exclusively the personal views of the authors. SWP Stiftung Wissenschaft und Politik German Institute for International and Security Affairs Ludwigkirchplatz 34 10719 Berlin Germany Phone +49 30 880 07-0 Fax +49 30 880 07-100 www.swp-berlin.org [email protected] ISSN 1863-1053 Translation by Meredith Dale (Updated English version of SWP-Studie 7/2015) Table of Contents 5 Problems and Recommendations 7 Jihadism in Africa: An Introduction Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 13 Al-Shabaab: Youth without God Annette Weber 31 Libya: A Jihadist Growth Market Wolfram Lacher 51 Going “Glocal”: Jihadism in Algeria and Tunisia Isabelle Werenfels 69 Spreading Local Roots: AQIM and Its Offshoots in the Sahara Wolfram Lacher and Guido Steinberg 85 Boko Haram: Threat to Nigeria and Its Northern Neighbours Moritz Hütte, Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 99 Conclusions and Recommendations Guido Steinberg and Annette Weber 103 Appendix 103 Abbreviations 104 The Authors Problems and Recommendations Jihadism in Africa: Local Causes, Regional Expansion, International Alliances The transnational terrorism of the twenty-first century feeds on local and regional conflicts, without which most terrorist groups would never have appeared in the first place. That is the case in Afghanistan and Pakistan, Syria and Iraq, as well as in North and West Africa and the Horn of Africa. -

Ansar Al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST)

Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST) Name: Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST) Type of Organization: Insurgent non-state actor religious social services provider terrorist transnational violent Ideologies and Affiliations: ISIS–affiliated group Islamist jihadist Qutbist Salafist Sunni takfiri Place of Origin: Tunisia Year of Origin: 2011 Founder(s): Seifallah Ben Hassine Places of Operation: Tunisia Overview Also Known As: Al-Qayrawan Media Foundation1 Partisans of Sharia in Tunisia7 Ansar al-Sharia2 Shabab al-Tawhid (ST)8 Ansar al-Shari’ah3 Supporters of Islamic Law9 Ansar al-Shari’a in Tunisia (AAS-T)4 Supporters of Islamic Law in Tunisia10 Ansar al-Shari’ah in Tunisia5 Supporters of Sharia in Tunisia11 Partisans of Islamic Law in Tunisia6 Executive Summary: Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST) was a Salafist group that was prominent in Tunisia from 2011 to 2013.12 AST sought to implement sharia (Islamic law) in the country and used violence in furtherance of that goal under the banner of hisbah (the duty to command moral acts and prohibit immoral ones).13 AST also actively engaged in dawa (Islamic missionary work), which took on many forms but were largely centered upon Ansar al-Sharia in Tunisia (AST) the provision of public services.14 Accordingly, AST found a receptive audience among Tunisians frustrated with the political instability and dire economic conditions that followed the 2011 Tunisian Revolution.15 The group received logistical support from al-Qaeda central, al-Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM), Ansar al-Sharia in Libya (ASL), and later, from ISIS.16 AST was designated as a terrorist group by the United States, the United Nations, and Tunisia, among others.17 AST was originally conceived in a Tunisian prison by 20 Islamist inmates in 2006, according to Aaron Zelin at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy. -

The Al Qaeda Network a New Framework for Defining the Enemy

THE AL QAEDA NETWORK A NEW FRAMEWORK FOR DEFINING THE ENEMY KATHERINE ZIMMERMAN SEPTEMBER 2013 THE AL QAEDA NETWORK A NEW FRAMEWORK FOR DEFINING THE ENEMY KATHERINE ZIMMERMAN SEPTEMBER 2013 A REPORT BY AEI’S CRITICAL THREATS PROJECT ABOUT US About the Author Katherine Zimmerman is a senior analyst and the al Qaeda and Associated Movements Team Lead for the Ameri- can Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project. Her work has focused on al Qaeda’s affiliates in the Gulf of Aden region and associated movements in western and northern Africa. She specializes in the Yemen-based group, al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula, and al Qaeda’s affiliate in Somalia, al Shabaab. Zimmerman has testified in front of Congress and briefed Members and congressional staff, as well as members of the defense community. She has written analyses of U.S. national security interests related to the threat from the al Qaeda network for the Weekly Standard, National Review Online, and the Huffington Post, among others. Acknowledgments The ideas presented in this paper have been developed and refined over the course of many conversations with the research teams at the Institute for the Study of War and the American Enterprise Institute’s Critical Threats Project. The valuable insights and understandings of regional groups provided by these teams directly contributed to the final product, and I am very grateful to them for sharing their expertise with me. I would also like to express my deep gratitude to Dr. Kimberly Kagan and Jessica Lewis for dedicating their time to helping refine my intellectual under- standing of networks and to Danielle Pletka, whose full support and effort helped shape the final product. -

Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation

Images of the Past: Nostalgias in Modern Tunisia Dissertation Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By David M. Bond, M.A. Graduate Program in Near Eastern Languages and Cultures The Ohio State University 2017 Dissertation Committee: Sabra J. Webber, Advisor Johanna Sellman Philip Armstrong Copyrighted by David Bond 2017 Abstract The construction of stories about identity, origins, history and community is central in the process of national identity formation: to mould a national identity – a sense of unity with others belonging to the same nation – it is necessary to have an understanding of oneself as located in a temporally extended narrative which can be remembered and recalled. Amid the “memory boom” of recent decades, “memory” is used to cover a variety of social practices, sometimes at the expense of the nuance and texture of history and politics. The result can be an elision of the ways in which memories are constructed through acts of manipulation and the play of power. This dissertation examines practices and practitioners of nostalgia in a particular context, that of Tunisia and the Mediterranean region during the twentieth and early twenty-first centuries. Using a variety of historical and ethnographical sources I show how multifaceted nostalgia was a feature of the colonial situation in Tunisia notably in the period after the First World War. In the postcolonial period I explore continuities with the colonial period and the uses of nostalgia as a means of contestation when other possibilities are limited. -

Prediction Improvement of Potential PV Production Pattern, Imagery Satellite‑Based A

www.nature.com/scientificreports OPEN Prediction improvement of potential PV production pattern, imagery satellite‑based A. Ben Othman1,3, K. Belkilani1,2* & M. Besbes1,2 The results obtained by using an existing model to estimate global solar radiation (GHI) in three diferent locations in Tunisia. These data are compared with GHI meteorological measurements and PV_Gis satellite imagery estimation. Some statistical indicators (R, R2, MPE, AMPE, MBE, AMBE and RMSE) have been used to measure the performance of the used model. Correlation coefcient for the diferent stations was close to 1.0. The meteorology and satellite determination coefcient (R2) were also near 1.0 except in the case of Nabeul station in which the meteorology measurements (R) were equals to 0.5848 because of the loss of data in this location due to meteorological conditions. This numerical model provides the best performance according to statistical results in diferent locations; therefore, this model can be used to estimate global solar radiation in Tunisia. The R square values are used as a statistical indicator to demonstrate that the model’s results are compatible with those of meteorology with a percentage of error less than 10%. Knowledge of local solar radiation is essential for many applications. Despite the importance of solar radia- tion measurements, this information’s source is not available due to the high cost of the sensors and it needs of continuous maintenance and calibration requirements 1–3. Te limited coverage of radiation values dictates the need to develop models to estimate solar radiation based on other more readily available, data 4–8. -

Tunisia Minube Travel Guide

TUNISIA MINUBE TRAVEL GUIDE The best must-see places for your travels, all discovered by real minube users. Enjoy! TUNISIA MINUBE TRAVEL GUIDE 1,991,000 To travel, discover new places, live new experiences...these are what travellers crave, and it ´s what they'll find at minube. The internet and social media have become essential travel partners for the modern globetrotter, and, using these tools, minube has created the perfect travel guides. 1,057,000 By melding classic travel guide concepts with the recommendations of real travellers, minube has created personalised travel guides for thousands of top destinations, where you'll find real-life experiences of travellers like yourself, photos of every destination, and all the information you\´ll need to plan the perfect trip.p. In seconds, travellers can create their own guides in PDF, always confident with the knowledge that the routes and places inside were discovered and shared by real travellers like themselves. 2,754,500 Don't forget that you too can play a part in creating minube travel guides. All you have to do is share your experiences and recommendations of your favorite discoveries, and you can help other travelers discover these exciting corners of the world. 3,102,500 Above all, we hope you find it useful. Cheers, The team at minube.net 236 What to see in Tunisia Page 2 Ruins Beaches 4 5 The Baths of Carthage Djerba Beach Virtu: The truth is that with an organized excursion you do lantoni: When I was at the beach I went to a club hotel not have much time for anything, and in my case I had a few ideally situated. -

Patterns of Complexity: Art and Design of Morocco and Tunisia 2011 2

Patterns of Complexity: The Art and Design of Morocco and Tunisia Fulbright-Hays Seminar Abroad Curriculum Project 2011 Sue Uhlig, Continuing Lecturer in Art and Design at Purdue University Religious Diversity in the Maghreb From June 12 to July 21, 2011, I was one of sixteen post-secondary educators who participated in the Fulbright-Hays Seminars Abroad program to Morocco and Tunisia. During those six weeks, we were immersed in the culture of the two North African countries, visiting significant historical and cultural attractions, attending lectures daily, tasting regional cuisine, and taking Arabic language classes for the first two weeks. The topic of the seminar was “Religious Diversity in the Maghreb: Morocco and Tunisia,” so lectures were focused primarily on Islamic topics, such as Moroccan Islam and Sufism, with some topics covering Judaism. We were treated to two musical performances, one relating to Judeo-Spanish Moroccan narrative songs and the other by Gnawa musicians. Visits to Christian churches, Jewish museums and synagogues, and Islamic mosques rounded out the religious focus. The group was in Morocco for a total of four weeks and Tunisia for two. In Morocco, we visited the cities of: Rabat* Casablanca* Sale Beni Mellal* Fes* Azilal Volubilis Amezray* Moulay Idriss Zaouia Ahansal Sefrou Marrakech* Ifrane In Tunisia, we visited the following cities: Tunis* Monastir Carthage Mahdia* Sidi Bou Said El Jem La Marsa Sfax Kairouan Kerkennah Islands* Sousse* Djerba* * cities with an overnight stay For more information, you may contact me at [email protected]. I also have my photos from this seminar on Flickr. http://www.flickr.com/photos/25315113@N08/ Background Being an art educator, teaching art methods classes to both art education and elementary education majors, as well as teaching a large lecture class of art appreciation to a general student population, I wanted to focus on the art and design of Morocco and Tunisia for this curriculum project. -

Doc.Rero.Ch Investigated (Bouchet Et Al

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by RERO DOC Digital Library Published in "Swiss Journal of Geosciences 111(3): 589–606, 2018" which should be cited to refer to this work. Distribution of benthic foraminiferal assemblages in the transitional environment of the Djerba lagoon (Tunisia) Akram El Kateb1 • Claudio Stalder2 • Christoph Neururer1 • Robin Fentimen1 • Jorge E. Spangenberg3 • Silvia Spezzaferri1 Abstract The eastern edge of the Djerba Island represents an important tourist pole. However, studies describing the environmental processes affecting this Island are scarce. Although never studied before, the peculiar Djerba lagoon is well known by the local population and by tourists. In July 2014, surface sediment and seawater samples were collected in this lagoon to measure grain size, organic matter content and living foraminiferal assemblages to describe environmental conditions. Seawater samples were also collected and the concentration of 17 chemical elements were measured by ICP-OES. The results show that a salinity gradient along the studied transect clearly impacts seagrass distribution, creating different environmental conditions inside the Djerba lagoon. Biotic and abiotic parameters reflect a transitional environment from hypersaline to normal marine conditions. Living benthic foraminifera show an adaptation to changing conditions within the different parts of the lagoon. In particular, the presence of Ammonia spp. and Haynesina depressula correlates with hypersaline waters, whilst Brizalina striatula characterizes the parts of the lagoon colonized by seagrass. Epifaunal species, such as Rosalina vilardeboana and Amphistegina spp. colonize hard substrata present at the transition between the lagoon and the open sea. Keywords Lagoon Á Djerba Island Á Foraminifera Á Transitional environment 1 Introduction (hypersaline conditions), depending on the hydrological balance (Kjerfve 1994). -

The Tunisian-Libyan Jihadi Connection | the Washington Institute

MENU Policy Analysis / Articles & Op-Eds The Tunisian-Libyan Jihadi Connection by Aaron Y. Zelin Jul 6, 2015 Also available in Arabic ABOUT THE AUTHORS Aaron Y. Zelin Aaron Y. Zelin is the Richard Borow Fellow at the Washington Institute for Near East Policy where his research focuses on Sunni Arab jihadi groups in North Africa and Syria as well as the trend of foreign fighting and online jihadism. Articles & Testimony A relationship that dates back decades deserves closer attention, and could well lead to repeat Islamic State attacks on Tunisian soil. t should have come as no surprise that Seifeddine Rezgui, the individual who attacked tourists in Sousse, Tunisia, I more than a week ago, had trained at a camp in Libya. The attack represented the continuation of a relationship between Tunisian and Libyan militants that, having intensified since 2011, goes back to the 1980s. The events in Sousse are a stark reminder of this relationship: a connection that is set to continue should the Islamic State (IS) choose to repeat attacks in Tunisia in the coming months. Brief History on the Tunisian-Libyan Militant Nexus A lthough Ennahda did not explicitly call for individuals to fight against the Soviets during the Afghan jihad, militants in the mujahedeen were regularly involved in facilitation and logistical networks that brought Libyans to the region. Additionally, according to Noman Benotman, a former shura council member of the Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) in Afghanistan in the 1980s, Libyans alongside Abdul Rasul Sayyaf, the Afghan leader of Ittihad- e-Islami, attempted to help the Tunisians create their own military camp and organization. -

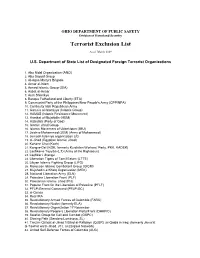

Terrorist Exclusion List

OHIO DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY Division of Homeland Security Terrorist Exclusion List As of March 2009 U.S. Department of State List of Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations 1. Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) 2. Abu Sayyaf Group 3. Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade 4. Ansar al-Islam 5. Armed Islamic Group (GIA) 6. Asbat al-Ansar 7. Aum Shinrikyo 8. Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) 9. Communist Party of the Philippines/New People's Army (CPP/NPA) 10. Continuity Irish Republican Army 11. Gama’a al-Islamiyya (Islamic Group) 12. HAMAS (Islamic Resistance Movement) 13. Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM) 14. Hizballah (Party of God) 15. Islamic Jihad Group 16. Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) 17. Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM) (Army of Mohammed) 18. Jemaah Islamiya organization (JI) 19. al-Jihad (Egyptian Islamic Jihad) 20. Kahane Chai (Kach) 21. Kongra-Gel (KGK, formerly Kurdistan Workers' Party, PKK, KADEK) 22. Lashkar-e Tayyiba (LT) (Army of the Righteous) 23. Lashkar i Jhangvi 24. Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) 25. Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) 26. Moroccan Islamic Combatant Group (GICM) 27. Mujahedin-e Khalq Organization (MEK) 28. National Liberation Army (ELN) 29. Palestine Liberation Front (PLF) 30. Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) 31. Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLF) 32. PFLP-General Command (PFLP-GC) 33. al-Qa’ida 34. Real IRA 35. Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) 36. Revolutionary Nuclei (formerly ELA) 37. Revolutionary Organization 17 November 38. Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front (DHKP/C) 39. Salafist Group for Call and Combat (GSPC) 40. Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso, SL) 41. -

Terrorist Exclusion List

OHIO DEPARTMENT OF PUBLIC SAFETY Division of Homeland Security Terrorist Exclusion List As of July 20, 2006 U.S. Department of State List of Designated Foreign Terrorist Organizations 1. Abu Nidal Organization (ANO) 2. Abu Sayyaf Group 3. Al-Aqsa Martyrs Brigade 4. Ansar al-Islam 5. Armed Islamic Group (GIA) 6. Asbat al-Ansar 7. Aum Shinrikyo 8. Basque Fatherland and Liberty (ETA) 9. Communist Party of the Philippines/New People's Army (CPP/NPA) 10. Continuity Irish Republican Army 11. Gama’a al-Islamiyya (Islamic Group) 12. HAMAS (Islamic Resistance Movement) 13. Harakat ul-Mujahidin (HUM) 14. Hizballah (Party of God) 15. Islamic Jihad Group 16. Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU) 17. Jaish-e-Mohammed (JEM) (Army of Mohammed) 18. Jemaah Islamiya organization (JI) 19. al-Jihad (Egyptian Islamic Jihad) 20. Kahane Chai (Kach) 21. Kongra-Gel (KGK, formerly Kurdistan Workers' Party, PKK, KADEK) 22. Lashkar-e Tayyiba (LT) (Army of the Righteous) 23. Lashkar i Jhangvi 24. Liberation Tigers of Tamil Eelam (LTTE) 25. Libyan Islamic Fighting Group (LIFG) 26. Moroccan Islamic Combatant Group (GICM) 27. Mujahedin-e Khalq Organization (MEK) 28. National Liberation Army (ELN) 29. Palestine Liberation Front (PLF) 30. Palestinian Islamic Jihad (PIJ) 31. Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine (PFLF) 32. PFLP-General Command (PFLP-GC) 33. al-Qa’ida 34. Real IRA 35. Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) 36. Revolutionary Nuclei (formerly ELA) 37. Revolutionary Organization 17 November 38. Revolutionary People’s Liberation Party/Front (DHKP/C) 39. Salafist Group for Call and Combat (GSPC) 40. Shining Path (Sendero Luminoso, SL) 41. -

The Jasmine Revolution and the Tourism Industry in Tunisia

UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones Fall 2011 The Jasmine Revolution and the Tourism Industry in Tunisia Mohamed Becheur University of Nevada, Las Vegas Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalscholarship.unlv.edu/thesesdissertations Part of the International Business Commons, Recreation Business Commons, and the Tourism and Travel Commons Repository Citation Becheur, Mohamed, "The Jasmine Revolution and the Tourism Industry in Tunisia" (2011). UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones. 1141. http://dx.doi.org/10.34917/2523139 This Professional Paper is protected by copyright and/or related rights. It has been brought to you by Digital Scholarship@UNLV with permission from the rights-holder(s). You are free to use this Professional Paper in any way that is permitted by the copyright and related rights legislation that applies to your use. For other uses you need to obtain permission from the rights-holder(s) directly, unless additional rights are indicated by a Creative Commons license in the record and/or on the work itself. This Professional Paper has been accepted for inclusion in UNLV Theses, Dissertations, Professional Papers, and Capstones by an authorized administrator of Digital Scholarship@UNLV. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Running head: THE JASMINE REVOLUTION 1 THE JASMINE REVOLUTION AND THE TOURISM INDUSTRY IN TUNISIA by Mohamed Becheur Bachelor of Finance University Paris Dauphine, France 2009 A professional paper submitted in partial