Re-Considering Margaret Horsfield's Cougar Annie's Garden

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Xrvdx/ ^(Au^Rjuo/ H Islror •

3%D1_ ©'4 2_ -HMM xRvdx/ ^(Au^rJUo/ H ISlrOR • Journal of the British Columbia Historical Federation | Vol.41 No. 2 | $5.00 This Issue: Booze | No Booze | Maps | Books | and more British Columbia History Journal of the British Columbia Historical British Columbia Historical Federation A charitable society under the Income Tax Act Organized 31 October 1922 Federation Published four times a year. ISSN: print 1710-7881 online 1710-792X PO Box 5254, Station B., Victoria BC V8R 6N4 British Columbia History welcomes stories, studies, Under the Distinguished Patronage of His Honour and news items dealing with any aspect of the The Honourable Steven L. Point, OBC history of British Columbia, and British Columbians. Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia Please submit manuscripts for publication to the Honorary President Editor, British Columbia History, Ron Hyde John Atkin, 921 Princess Avenue, Vancouver BC V6A 3E8 e-mail: [email protected] Officers Book reviews for British Columbia History, Frances Gundry, Book Review Editor, President: Ron Greene BC Historical News, PO Box 1351, Victoria V8W 2W7 P.O. Box 5254, Station B., Victoria, BC V8R 6N4 Phone 250.598.1835 Fax 250.598.5539 e-mail: [email protected] [email protected] Subscription 8t subscription information: First Vice President: Gordon Miller Alice Marwood Pilot Bay 1126 Morrell Circle, Nanaimo V9R 6K6 211 - 14981 - 101A Avenue Surrey BCV3R0T1 vp1 ©bchistory.ca Phone 604-582-1548 email: [email protected] Second Vice President: Tom Lymbery 1979 ChainsawAve., Gray Creek VOB 1S0 Subscriptions: $18.00 per year Phone 250.227.9448 Fax 250.227.9449 For addresses outside Canada add $10.00 [email protected] Secretary: Janet M. -

Bubbles and Spirals: the Memoirs of C

Bubbles and Spirals: The Memoirs of C. S. Buzz Holling This is the second edition of Bubbles and Spirals: The Memoirs of Buzz Holling, based on a first edition published in June 2016. Further editions may follow. This edition is published on the occasion of the Resilience 2017 Conference in Stockholm, Sweden, August 20-23, 2017. Conference Sponsors: Stockholm Resilience Centre, Resilience Alliance Current web site: http://resilience2017.org/ Citation: C.S. Holling. 2017. Bubbles and Spirals: The Memoirs of C. S. Buzz Holling (Second Edition). Available online in multiple electronic formats at: http://www.stockholmresilience.org/holling-memoirs © C.S. Holling 2017 © Resilience Alliance 2017 Version 37 – JTS August 17, 2017 This memoir is dedicated to the RAYS, the Resilience Alliance Young Scholars. Bubbles and Spirals - 1 - Second Edition Table of Contents Table of Contents .......................................................................................... 1 Table of Figures ............................................................................................. 2 Preface: As good as it gets! ........................................................................... 3 The Glass Bubbles ......................................................................................... 5 Foreword: An unexpected neighbor ............................................................. 6 Introduction ................................................................................................ 10 The Beginning of Beginnings ...................................................................... -

Biutish C0lumma Winter 2000/2001 $5.00 Histoiuc NEWS ISSN 1195-8294 Journal of the British Columbia Historical Federation

Volume 34, No. i BIuTIsH C0LuMmA Winter 2000/2001 $5.00 HIsToiuc NEWS ISSN 1195-8294 Journal of the British Columbia Historical Federation - r The Canadian Pacific’s Crowsnest Route tram at Cranbrook about 1900. Archival Adventures Remember the smell of coal and steam? The Flood of 1894 Robert Turner, curator emeritus at the Royal British Columbia Museum in Victoria, is an authority on the history of railroads and steamships in Yellowhead books on British Columbia and he has written and published a dozen Cedar Cottage BC’s transportation history In this issue he writes about the Crowsnest Route. “Single Tax” Taylor Patricia Theatre Index 2000 British Columbia Historical News British Columbia Historical Federation Journal of the P0 Box S254, STATIoN B., VICToRIA BC V8R 6N4 British Columbia Historical Federation A CHARITABLE SOCIETY UNDER THE INCOME TAX ACT Published Winter, Spring, Summer, and Fall. EDITOR: ExECuTIVE Fred Braches HoNolcsisY PATRON: His HONOUR, THE H0N0ISABLE GARDE B. GARD0M, Q.C. P0 Box 130 HON0eARY PREsIDENT:AuCE GLANvILLE Whonnock BC, V2W 1V9 Box 746 Phone (604) 462-8942 GISAND FORKS, BC VoM aHo brachesnetcom.ca OFFICERs BooK Rrvxrw EDITOR: PREsIDEi’cr:WAYNE DE5R0CHER5 Anne Yandle #2 - 6712 BARER ROAD, DELTA BC 3450 West 20th Avenue V4E 2V3 PHONE (604) 599-4206 (604)507-4202 Vancouver BC, V6S 1E4 FAX. [email protected] FIEsT VICE PRESIDENT: RoJ.V PALLANT Phone (604) 733-6484 1541 MERLYNN CREsCENT. NoRTHVp,NCoUvER 2X9 yandleinterchange. ubc.ca BC V7J PHONE (604) 986-8969 [email protected] SUBscRIPTION SEcRETARY: -

AABC Newsletter Is a Quarterly Publication of the Archives Association of British Features Columbia

aabc.ca memorybc.ca Honorary Patron: The Honourable Iona Campagnolo, PC, CM, OBC, Lieutenant-Governor of British Columbia Volume 16 No.1 Winter 2006 ISSN 1193-3165 Newsletter homepage aabc.bc.ca/aabc/newsletter How to join the AABC Table of Contents aabc.bc.ca/aabc/meminfo.html The AABC Newsletter is a quarterly publication of the Archives Association of British Features Columbia. Opinions expressed are not necessarily Vancouver Art Gallery exhibition entitled "Classified Materials: those of the AABC. Accumulations, Archives, Artists" exposes the sad state of institutional archives by Jessica Bushey Got news? Send AABC news, Classified Materials: Accumulations, Archives, Artists: Vancouver tips, suggestions or letters to Art Gallery, October 15 2005 – January 2, 2006 by Krisztina Laszlo the acting editor: [vacant] Columns / Regular Items Deadlines for each issue are one month prior to publication. B.C. Archival Network News AABC Workshop: "Managing Electronic Records" Editorial Board: Community News Kelly Harms SFU bowls away the Competition by Lisa Beitel Greg Kozak Luciana Duranti receives the UBC Killam Research Prize by Greg Jennifer Mohan Kozak Chris Hives 2006 ACA Institute by Denise Jones [vacant], Editor Leslie Field, Technical Editor Next Issue: May 1, 2006 Please supply all submissions in electronic format, as either .txt, WP7, WORD 97/2000/XP or via e-mail Last updated April 10, 2006 aabc.ca memorybc.ca Volume 16 No. 1 Winter 2006 Vancouver Art Gallery exhibition entitled "Classified Materials: Accumulations, Archives, Artists" -

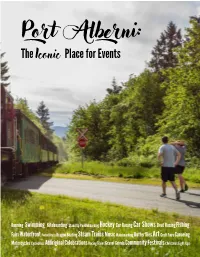

Events Guide with an Emphasis on Community Participation

SHARIE MINIONS MORTGAGE BROKER O. 250.730.0239 F. 887.474.5346 E. [email protected] “I find a lot of people don’t know what a mortgage broker is and that we are a free service. I have 25-plus lenders to choose from who all come with their own rates and products. I am paid by commission so it is a free service to you and commissions very vary little lender to lender, so it allows me to be an unbiased source of information for you.” SharieMinions.com Paper Chase 10km Sproat Lake Regatta ACDC Pride Fest Dragon Boat Regatta Music By The Sea Port Day Sproat Lake Wake and Skate Butterfly Effect Outrigger Race Father’s Day at the Mill Five Acre Shaker McLean Mill Thunder in the Valley Solstice Arts Fest Salmon Festival Kiting For Kids Fall Fair Sunset Market Alberni Valley Bulldogs Canada Day Toy Run Okee Dokee Slo-Pitch Port Alberni at 50 Tri-Conic Challenge Fall and Winter at McLean Mill Our Town Cyclocross Race Jane Austen Blue Marlin Sail Past Photos Credit Ad Sales: Cover: Dan Fredlund Lyndon Cassell Megan Warrender Alberni Valley News Music By The Sea Jodi Irving Brenda Widdess Parks and Recreation Bill Collette Darran Chaisson Russ Widdess Graphic Design: Kristi Dobson Sarah Etoile redinksolutions.ca Mike Ruttan, Mayor, City of Port Alberni The City of Port Alberni is proud to host numerous events throughout the year that celebrate and promote the rich and multi-faceted cul- ture of our community. From fundraisers, concerts, parades, sporting events, and festivals to dynamic family-friendly events, there is always something to see and discover. -

ALBERNI-CLAYOQUOT REGIONAL DISTRICT ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT STRATEGY – 1998 Prepared by the Economic Development Commission RECOMMENDATIONS COMMENTS 1

Alberni-Clayoquot Regional District COMMITTEE-OF-THE-WHOLE WEDNESDAY, FEBRUARY 25, 2015, 10:00 AM Regional District Board Room, 3008 Fifth Avenue, Port Alberni, BC AGENDA PAGE # 1. CALL TO ORDER Recognition of Traditional Territories. 2. APPROVAL OF AGENDA (motion to approve, including late items required 2/3 majority vote) 3. DECLARATIONS (conflict of interest or gifts) 4. PETITIONS, DELEGATIONS & PRESENTATIONS 2-16 a. Mr. Pat Deakin, Economic Development Officer, City of Port Alberni regarding Alberni-Clayoquot Regional District Contribution to City of Port Alberni Economic Development for 2015. 5. REQUEST FOR DECISIONS & BYLAWS a. REQUEST FOR DECISION 17-18 Alberni-Clayoquot Regional District Parks & Trails Strategic Plan 19-119 M-Irg/H. Adair-Plan Presentation THAT the Committee of the Whole recommend to the Board of Directors: 1. approval of the Alberni-Clayoquot Regional District Parks & Trails Strategic Plan; 2. establish the ACRD Parks & Trails Advisory Committee with representation from all areas; and 3. appoint two Directors to the ACRD Parks & Trails Advisory Committee to advise the Board of Directors on implementation of the Regional Parks & Trails Strategic Plan 6. OTHER BUSINESS 7 NEW BUSINESS 8 ADJOURN 1 CITY OF PORT ALBERNI City Hall 4850 Argyle Street Port Alberni, B.C. V9Y 1V8 Tel. (250) 723-2146 Fax: (250) 723-1003 COMMENTS TO THE BOARD OF THE ACRD RE ECONOMIC DEVELOPMENT WORK PLAN FOR 2015 From the Economic Development Manager, City of Port Alberni Bottom Line Recommendation: Increase the contribution to the economic development function to enable an investment in a regional economic development action plan. Rationalization for a Regional Economic Development Action Plan After a great deal of discussion last year, there were 8 deliverables identified for the Board’s investment in Economic Development in 2014. -

2006 Annual Report

In a conservation economy, growth Ecotrust Canada Annual Report 2006 is about‘getting rich slow.’ It is about ensuring that companies and communities profit on the interest, not capital, of nature. That means harvesting trees without destroying the rainforest ecosystem. It means fishing without erasing the very stocks that feed us. It means tapping into energy sources that are clean and renewable. But most of all, a conservation economy is about people — where they live, how they prosper. People, place and profit. That’s the conservation economy. Ecotrust Canada Annual Report 2006 / Page 1 Executive letter A Conscious Economy Al Gore’s film, An Inconvenient Truth, has arguably had a more transformative effect on how people think about the environment than any other single event of this generation. Now the hard part starts: turning awareness into action. That’s because “action” is often viewed only through the lens of consumerism. Drive a smarter car, buy a carbon offset, screw in a fluorescent light bulb — all of these actions worthy, but somehow not quite enough. If people — and by extension the governments we elect, and the companies we invest in or work for — all now have a heightened consciousness about the environment, why can’t we have a more conscious economy? Why is there such a yawning gap between the economy we want — one that delivers clean air, clean water, healthy food, good jobs and time to share with families — and an economy that overheats the planet and imperils us all? In a word, investment. With rare exceptions, there is vastly too little capital invested in enterprises that strive not just for a financial return, but for social and environmental returns as well. -

Let Me Tell You What I Know: Personal Story As Educational Praxis

LET ME TELL YOU WHAT I KNOW: PERSONAL STORY AS EDUCATIONAL PRAXIS By KAREN CHARLESON Integrated Studies Project submitted to Dr. Kadi Purru in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Integrated Studies Athabasca, Alberta June, 2008 Charleson 2 Table of Contents Abstract.………………………………………………………………………...………...3 Acknowledgements.………………………………………………………………..….…3 Dedication…………………………………………………………………………...……4 Let me tell you what I know Introduction ………………………………………………………………………..…….6 Story One: My Grandmother……………………………………………...…….….....9 Story Two: Estonia…………………………………………………………………….19 Story Three: A Danish Farmhouse…………………………………………………...25 Story Four: Sashmaray……………………………………………………...……...…31 Story Five: Sashmaray – Another Story…………………………………...………....43 Personal Story as Educational Praxis Introduction……………………………………………………………………..………47 Using Story in the Current Educational System………………………………….…..49 Intergenerational Learning……………………………………………………..……...55 The Right and Responsibility to Narrate: My Voice……….……………….………..57 Conclusion……………………………………………………………………………....60 A Closing Story………………………………………………………………………....62 Works Cited and Consulted……………………………………………………………65 Charleson 3 Abstract “Let me tell you what I know” is a series of personal stories written for my children and grandchildren. My stories provide some of the content, context, and familial/family connection that, as a mother and grandmother, I feel a responsibility to relate. These stories, like countless other personal stories from many different perspectives, -

Regular Agenda Attachments

ATTACHMENT(S) FOR REGULAR MEETING OF COUNCIL Tuesday, March 10, 2015 7:30 p.m. George Fraser Room, Ucluelet Community Centre 500 Matterson Drive, Ucluelet, B.C. CONTENTS: • Agenda Item 6.5 - Pacific Rim Education and Tourism Package Council Members: Mayor Dianne St. Jacques Councillor Sally Mole Councillor Randy Oliwa Councillor Marilyn McEwen Councillor Mayco Noel www.ucluelet.ca THIS PAGE LEFT BLANK INTENTIONALLY Subject: Pac Rim Education and Tourism Documents - for public release Attachments: Regional Education Asset Inventory_final.pdf; ATT00001.htm; Capacity Building Strategy revised Feb.5.pdf; ATT00002.htm; Pacific Rim Education Tourism Market Development Strategy 2015 .pdf; ATT00003.htm; Pacific Rim Education Tourism Market Development Research Results Report 2014.pdf; ATT00004.htm From: Tawney Lem [ mailto:[email protected] ] Sent: February-27-15 11:33 AM To: Iris Frank; Andrew Yeates; Josie Osborne; Rebecca Hurwitz; Randy Oliwa; Karl Wagner; Al McCarthy; Sally Mole; Dorothy Baert; James Frank; Francis Frank; Saya Masso; Barb Audet; Greg Blanchette; Dianne St. Jacques; Tammy Dorward; Patricia Abdulla; Tyson Touchie Subject: Pac Rim Education and Tourism Documents - for public release Hello all, At yesterday’s Steering Committee meeting, the group decided by consensus to make the final project reports available for public distribution. These documents are available for your use, and for distribution to others as you deem appropriate. Also based on committee direction, please make these documents available on your -

Standard of Conduct for Research in Northern Barkley and Clayoquot Sound Communities

Standard of Conduct for Research in Northern Barkley and Clayoquot Sound Communities Version 1.1 (updated December 2005) Developed through the Protocols Project of the Clayoquot Alliance for Research, Education and Training This document may be reproduced for educational, cultural and other non-commercial purposes providing the source (CLARET) and version (1.1) are fully acknowledged, as noted above. Standard of Conduct for Research in Northern Barkley and Clayoquot Sound Communities Developed through the Protocols Project of the Clayoquot Alliance for Research, Education and Training Contacts: Kelly Bannister (Victoria) Ph: 250-472-5016 Fax: 250-472-5060 Email: [email protected] Rebecca Vines (Ucluelet) Ph: 250-726-2086 Fax: 250-725-2384 Email: [email protected] Nadine Crookes (Long Beach) Ph: 250-726-4709 Fax: 250-726-4620 Email: [email protected] Gerry Schreiber (Ucluelet) Ph: 250-726-8665 Fax: 250-726-7269 Email: [email protected] Constructive comments for revising this document are encouraged and welcomed. Please contact one of the above individuals to give feedback. CONTENTS 1 Background p. 3 2 Introduction p. 4 3 Goals p. 5 4 Minimum Ethical Standards for Researchers p. 5-7 5 Additional Expectations of Researchers p. 7-8 6 Community Research Guidelines p. 8-12 7 List of Appendices p. 13 A. Acknowledgements p. 14-15 B. Map of Communities of Northern Barkley and Clayoquot Sound p. 16-17 C. Research Conducted in BC Parks p. 18-19 D. Research Conducted in National Parks p. 20 E. An Orientation to the Central Region Nuu-chah-nulth Nations p. -

Conference Program Page June 26-28, 2014 Victoria, British Columbia

June 26-28, 2014 Victoria, British Columbia Victoria, BC 39th Annual Conference June 26-28, 2014 Final Version 2014 Conference Program Page June 26-28, 2014 Victoria, British Columbia The Harvester King, the first Sidney-Anacortes Ferry, Image e-01417 courtesy of Royal BC Museum, BC Archives Table of Contents Welcome Letters ..........................................................................................................3 President, Association of Canadian Archivists...............................................................3 Prime Minister .............................................................................................................4 Lieutenant Governor of British Columbia .....................................................................4 Premier ........................................................................................................................5 Mayor of Victoria ........................................................................................................5 Committee Messages....................................................................................................6 Our sponsors and Exhibitors.........................................................................................7 Sessions Descriptions...................................................................................................8 Thursday, June 26 ........................................................................................................8 Friday, June 27...........................................................................................................12 -

2003 Annual Report

the nature of change 2003 annual report ecology ❘ economy ❘ equity mission Ecotrust Canada’s mission is to support the emer- gence of a conservation economy in the coastal temperate rain forest region of British Columbia. A conservation economy sustains itself on “princi- pled income” earned from activities that restore rather than deplete natural capital. We envision a region in which the economy results in social and ecological improvement rather than degradation. strategy Our strategy is to act as a catalyst and broker to create the institutions needed to envision, finance and grow the conservation economy; to support the conservation entrepreneurs that can give it expression; and to conserve and restore the land- scapes and marine ecosystems needed to provide its benchmarks of health. We offer tools and resources to people and organizations who promote positive change at the intersection of ecosystem conservation, economic opportunity and community vitality. Peter Buckland is building a new field studies centre at historic Cougar Annie’s Garden in Clayoquot Sound Ecotrust Canada works with entrepreneurs, local communities, First Nations, government, scien- tists, industry, and fellow conservationists. We are Ecotrust Canada aims agents of change in the ongoing search for true protection and sustainability of British Columbia’s to empower communities to unmatched natural capital. While not a membership organization, Ecotrust become a catalyst for change, Canada welcomes the support of all who would like to share in our work. Contributions to Ecotrust not the victims of it. Canada are tax deductible. Credit card donations may be made online at www.canadahelps.org. Revenue Canada Charitable Registration Number: 89474 9969 RR0001 2 a catalyst for change 2003 annual report igh on a ridge overlooking Hesquiat Harbour, The conservation economy embodies a new generation H the rainforest canopy frames a view of the of behaviour that is, simply, smarter.