I N T R O D U C T I O N the Famous Narrative of the Last Battle of Panipat

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

In the Name of Krishna: the Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town

In the Name of Krishna: The Cultural Landscape of a North Indian Pilgrimage Town A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE GRADUATE SCHOOL OF THE UNIVERSITY OF MINNESOTA BY Sugata Ray IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY Frederick M. Asher, Advisor April 2012 © Sugata Ray 2012 Acknowledgements They say writing a dissertation is a lonely and arduous task. But, I am fortunate to have found friends, colleagues, and mentors who have inspired me to make this laborious task far from arduous. It was Frederick M. Asher, my advisor, who inspired me to turn to places where art historians do not usually venture. The temple city of Khajuraho is not just the exquisite 11th-century temples at the site. Rather, the 11th-century temples are part of a larger visuality that extends to contemporary civic monuments in the city center, Rick suggested in the first class that I took with him. I learnt to move across time and space. To understand modern Vrindavan, one would have to look at its Mughal past; to understand temple architecture, one would have to look for rebellions in the colonial archive. Catherine B. Asher gave me the gift of the Mughal world – a world that I only barely knew before I met her. Today, I speak of the Islamicate world of colonial Vrindavan. Cathy walked me through Mughal mosques, tombs, and gardens on many cold wintry days in Minneapolis and on a hot summer day in Sasaram, Bihar. The Islamicate Krishna in my dissertation thus came into being. -

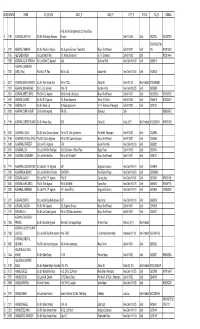

Sadar Bazar 1522 M/S Om Prakash Uppal 10 54 142 206

FOOD GRAIN DISTRIBUTION OF REGULAR PDS FOR MAY 2020 & PMGKAY FOR APRIL 2020 from 29/04/2020 to 09/05/2020 (As reported by FSOs) No of Beneficiaries District Circle No, Name FPS No FPS Name TOTAL AAY PRS PR CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 1522 M/S OM PRAKASH UPPAL 10 54 142 206 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 1528 M/S R C BAHAL 33 64 71 168 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 3103 M/S KEWAL SVARUP JAIN 53 93 345 491 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 3733 M/S RAM KUMAR PRAVIN KUMAR 4 19 979 1002 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 3891 M/S SHAIVACHARAN MAL GOVARDHAN DAS 42 158 448 648 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 3944 M/S SADHU RAM 0 141 573 714 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 3966 M/S MADAN LAL 88 124 351 563 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 4062 M/S KALA RAM 1 0 12 13 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 5541 M/S GUPTA STORE 100 208 822 1130 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 5718 M/S THAMBU RAM GUPTA 1 35 1247 1283 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 6008 M/S SHARMA STORE 44 153 521 718 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 6049 M/S DEVENDER SINGH 45 145 547 737 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 6116 M/S OM PRAKASH RAMESH CHANDER 48 128 447 623 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 6677 M/S RISHI PRAKASH 1 77 1060 1138 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 7078 M/S JITENDER STORE 53 243 686 982 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 7320 M/S SHIV KHADY BHANDAR 108 222 332 662 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 7321 M/S SWARN LATA MAHENDER PAL 19 96 255 370 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 7329 M/S AGGRAWAL AND BROTHERS 30 80 135 245 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 7445 M/S HANS RAJ AND SONS 10 32 934 976 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 7452 M/S PALIWAL STORE 9 40 1002 1051 CENTRAL 19 - SADAR BAZAR 9286 M/s Singh Store 0 -

Govardhan: Hindu Pilgrimage Town This Quiet Little Spot with Narrow

Govardhan: Hindu Pilgrimage Town by traveldesk This quiet little spot with narrow winding lanes is closely linked with Lord Krishna, the most loved deity in Hindu mythology. This mischievous god is said to have lived in these areas, and as such worship and devotion have a very tangible feel here. Govardhan is an important place of pilgrimage too. According to legend, Krishna once protected the people of Govardhan from the wrath of Indra, the God of Rain (also the great Warrior God). It so happened that Indra hurled a terrible thunderbolt at these poor people (for reasons quite unknown to us). So Krishna lifted a whole mountain, the nearby Mount Giriraj, and held it on his little finger for seven days and nights as an umbrella against the terrible rain and cyclone. Such were the miracles Krishna is supposed to have performed.Later Indra had to fall at Krishna's feet and ask for forgiveness, of course. ¤ Famous Temples There are lots of temples in Govardhan. The most interesting one is the 16th century Harideva Temple. Near this is a complex of chhatris (cenotaphs) of the Jat maharajas of Bharatpur which have some really nice frescoes. Their curved cornices and multiple domes and pavilions make them somewhat similar to the Rajput architectural pieces. There is another chhatri dedicated to the most illustrious Jat ruler, Suraj Mal, about 3km north of here. The ceiling has frescoes showing episodes from the life of the maharaja. Govardhan: Hindu Pilgrimage Town by traveldesk. -

Curley on Ray, 'Climate Change and the Art of Devotion: Geoaesthetics in the Land of Krishna, 1550-1850'

H-Asia Curley on Ray, 'Climate Change and the Art of Devotion: Geoaesthetics in the Land of Krishna, 1550-1850' Review published on Wednesday, March 25, 2020 Sugata Ray. Climate Change and the Art of Devotion: Geoaesthetics in the Land of Krishna, 1550-1850. Seattle: University of Washington Press, 2019. 264 pp. $70.00 (cloth), ISBN 978-0-295-74537-4. Reviewed by David Curley (Western Washington University) Published on H-Asia (March, 2020) Commissioned by Sumit Guha (The University of Texas at Austin) Printable Version: http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showpdf.php?id=54359 Curley on Ray, Climate Change Sugata Ray’s brilliant book, Climate Change and the Art of Devotion: Geoaesthetics in the Land of Krishna, proposes new questions for the discipline of art history. Using concepts and methods taken from material culture studies as well as from art history, Ray proposes reciprocal relations among the earth’s changing environment, ecological transformations brought about by the ways humans have lived upon the land and sea, and “theology, art practice, and an aesthetics of the natural world” (p. 20). As a case study, Ray has chosen the region of Braj in north India, first, because of repeated, disastrous droughts and famines in north India that seem to have been particularly severe from the mid-sixteenth century to the early eighteenth century, and second, because in the same period Gaudiya Vaishnavas made the whole region of Braj a sacred landscape. In the 1540s, about a decade earlier than the first severe recorded famine of the Little Ice Age, Gaudiya Vaishnava scholars residing in Braj began producing theologies of what Barbara Holdrege has called Krishna’s “mesocosmic embodiment” in the locality as a whole. -

S.No Application No Enrollment Number Name Father's Name State 1 DP-PRGRD/B1/1136 36PRGRD00001-19 TIRTHA SANKAR ROY CHANDAN

Diploma Programme on Panchayati Raj Governance & Rural Development(DP-PRGRD) List of students allotted to HIRD, Nilokheri, Haryana S.No Application No Enrollment Number Name Father's Name State 1 DP-PRGRD/B1/1136 36PRGRD00001-19 TIRTHA SANKAR ROY CHANDAN ROY WEST BENGAL 2 DP-PRGRD/B1/1145 36PRGRD00005-19 SURESH CHANDRA BARBER KISHAN LAL SEN RAJASTHAN 3 DP-PRGRD/B1/1151 36PRGRD00006-19 MANISH VAGHONA MANGI LAL VAGHONA RAJASTHAN 4 DP-PRGRD/B1/1230 36PRGRD00013-19 PRADIPTA KUMAR KAR NILAKANTHA KAR WEST BENGAL 5 DP-PRGRD/B1/1246 36PRGRD00015-19 HARJINDER SINGH DEV SINGH Punjab 6 DP-PRGRD/B1/1248 36PRGRD00016-19 KAMAL DEEP KAUR MANJIT SINGH PUNJAB 7 DP-PRGRD/B1/1303 36PRGRD00020-19 SHARAYU C PAWAR CHANDRAKANT S PAWAR Gujarat 8 DP-PRGRD/B1/1318 36PRGRD00023-19 NARENDER RAM KARAM SINGH Haryana 9 DP-PRGRD/B1/1428 36PRGRD00035-19 KULDEEP RAM ARJUN RAM Bihar 10 DP-PRGRD/B1/1436 36PRGRD00036-19 SIMMI KUMARI GANGADHAR TIWARI Jharkhand 11 DP-PRGRD/B1/1448 36PRGRD00039-19 SOURAV DUTTA Gopal Dutta Madhya Pradesh 12 DP-PRGRD/B1/1580 36PRGRD00046-19 AMIT KUMAR SURAJ MAL Haryana 13 DP-PRGRD/B1/1582 36PRGRD00047-19 RAM NARAYAN SINGH JEET SINGH RAJASTHAN 14 DP-PRGRD/B1/1587 36PRGRD00048-19 SURJEET KUMAR KALU RAM Haryana 15 DP-PRGRD/B1/1614 36PRGRD00053-19 PANKAJ Raghunandan Pandit Jharkhand 16 DP-PRGRD/B1/1618 36PRGRD00054-19 ASHISH KUMAR Surajmal Haryana 17 DP-PRGRD/B1/1659 36PRGRD00056-19 ANMOLA SHEKHAR MISHRA NIRMALENDU SHEKHAR MISHRA Bihar 18 DP-PRGRD/B1/1672 36PRGRD00058-19 SONU KUMAR Bhagwan Singh Haryana 19 DP-PRGRD/B1/1730 36PRGRD00065-19 BIKAS CHANDRA -

P Age | 1 Mathura Vrindavan Yaatraa

P a g e | 1 Mathura Vrindavan Yaatraa Mathura Vrindavan Yaatra As you all knows that, Mathura Vrindavan is world famous Hindu religious tourism place and famous for Lord Krishna birthplace, temple and activates. We are placing some information regarding Mathura Vrindavan Tour Packages. During Mathura Vrindavan tour, you may cover the following places. Place to Visits : Mathura : Lord krishna Birthplace, Dwarkadhish Temple, Birla Temple, Mathura Museum, Yamuna Ghat's Vrindavan: Bankey Bihari Temple, Iskcon Temple, Radha Ballabh Temple, Prem Mandir, Nidhi Van, Kesi Ghata and Yamuna River etc. P a g e | 2 Mathura Vrindavan Yaatraa Gokul: Childhood living place of lord Krishna Near Mathura Nand Gayon: Village of lord krishna relatives Goverdhan: Goverdhan Mountain and Parikrma, Radha Kund, Kusam Sarowar Barsana: Birthplace of Radha Rani and Temples Radha Rani: Famous Temple of Radha Rani near Mathura Bhandiravan: Radhak Krishn Marriage Place, Near Mant Mathura TOURIST PLACE AT DISTRICT MATHURA MATHURA What to See SHRI KRISHNA JANMA BHUMI : The Birth Place of Lord Krishna JAMA MASJID : Built by Abo-inNabir-Khan in 1661.A.D. the mosque has 4 lofty minarets, with bright colored plaster mosaic of which a few panels currently exist. VISHRAM GHAT : The sacred spot where Lord Krishna is believed to have rested after slaying the tyrant Kansa. DWARKADHEESH TEMPLE : Built in 1814, it is the main temple in the town. During the festive days of Holi, Janmashthami and Diwali, it is decorated on a grandiose scale. GITA MANDIR : Situated on the city outskirts, the temple carving and painting are a major attraction. GOVT. MESEUM : Located at Dampier Park, it has one of the finest collection of archaeological interest. -

Faculty Details Proforma for DU Web-Site

Faculty Details proforma for DU Web-site Title Professor First Name R.B. Last Singh Photograph Name Designation Professor Address Department of Geography, Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi, Delhi-110007, INDIA Phone No Office 011-27666783 Residence 143 Kadambari, Sector -9, Rohini, Delhi-110085 Phone:27553850 Mobile 09971950226 Email [email protected] Web-Page www.du.ac.in/geography Educational Qualifications Degree Institution Year Ph.D. Banaras Hindu University 1981 PG Banaras Hindu University 1977 UG Banaras Hindu University 1975 Diploma in Statistical Banaras Hindu University 1979 Methods GIS Training UNITAR/UNEP – GRID and EPFL, Switzerland 1989 Career Profile Organisation / Institution Designation Duration University of Delhi Professor 2002 onwards University of Delhi UGC Research Scientist - C (Professor) 1996 to 2002 University of Delhi UGC Research Scientist -B (Reader) 1988 to 1996 University of Delhi Lecturer 1985 to 1988 Banaras Hindu University CSIR POOL Officer 1983 to 1985 Administrative Assignments Head-Department of Geography, Delhi School of Economics, University of Delhi. Delhi -3 years (2013-early 2016) R.T., Warden and Acting Provost of Gwyer Hall, Univ.of Delhi -more than 13 years (April 1987 to September 2000). Areas of Interest / Specialization Environmental Studies, Urban Health, Remote Sensing and GIS, Disaster Management, Climate Change Subjects Taught Taught following courses to M. A. and M. Phil. programme at University of Delhi since 1985: Environment and Ecology, Natural Hazards and Disaster Management, Fundamentals of Remote Sensing and GIS, Environmental Impact Assessment, Urban Impacts on Natural Resources and Environment, Environmental Studies, Ecological Issues in Development, GIS and Remote Sensing, Environmental Problems and Policies, Environmental Security: Problems and Policies, Man and Environment, Biogeography, Regional Planning & Development. -

Main Voter List 08.01.2018.Pdf

Sl.NO ADM.NO NAME SO_DO_WO ADD1_R ADD2_R CITY_R STATE TEL_R MOBILE 61-B, Abul Fazal Apartments 22, Vasundhara 1 1150 ACHARJEE,AMITAVA S/o Shri Sudhamay Acharjee Enclave Delhi-110 096 Delhi 22620723 9312282751 22752142,22794 2 0181 ADHYARU,YASHANK S/o Shri Pravin K. Adhyaru 295, Supreme Enclave, Tower No.3, Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 745 9810813583 3 0155 AELTEMESH REIN S/o Late Shri M. Rein 107, Natraj Apartments 67, I.P. Extension Delhi-110 092 Delhi 9810214464 4 1298 AGARWAL,ALOK KRISHNA S/o Late Shri K.C. Agarwal A-56, Gulmohar Park New Delhi-110 049 Delhi 26851313 AGARWAL,DARSHANA 5 1337 (MRS.) (Faizi) W/o Shri O.P. Faizi Flat No. 258, Kailash Hills New Delhi-110 065 Delhi 51621300 6 0317 AGARWAL,MAM CHANDRA S/o Shri Ram Sharan Das Flat No.1133, Sector-29, Noida-201 301 Uttar Pradesh 0120-2453952 7 1427 AGARWAL,MOHAN BABU S/o Dr. C.B. Agarwal H.No. 78, Sukhdev Vihar New Delhi-110 025 Delhi 26919586 8 1021 AGARWAL,NEETA (MRS.) W/o Shri K.C. Agarwal B-608, Anand Lok Society Mayur Vihar Phase-I Delhi-110 091 Delhi 9312059240 9810139122 9 0687 AGARWAL,RAJEEV S/o Shri R.C. Agarwal 244, Bharat Apartment Sector-13, Rohini Delhi-110 085 Delhi 27554674 9810028877 11 1400 AGARWAL,S.K. S/o Shri Kishan Lal 78, Kirpal Apartments 44, I.P. Extension, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22721132 12 0933 AGARWAL,SUNIL KUMAR S/o Murlidhar Agarwal WB-106, Shakarpur, Delhi 9868036752 13 1199 AGARWAL,SURESH KUMAR S/o Shri Narain Dass B-28, Sector-53 Noida, (UP) Uttar Pradesh0120-2583477 9818791243 15 0242 AGGARWAL,ARUN S/o Shri Uma Shankar Agarwal Flat No.26, Trilok Apartments Plot No.85, Patparganj Delhi-110 092 Delhi 22433988 16 0194 AGGARWAL,MRIDUL (MRS.) W/o Shri Rajesh Aggarwal Flat No.214, Supreme Enclave Mayur Vihar Phase-I, Delhi-110 091 Delhi 22795565 17 0484 AGGARWAL,PRADEEP S/o Late R.P. -

Shows a Close Resemblance to Certain Early Mughal Edifices

Scholarly Research Journal for Interdisciplinary Studies, Online ISSN 2278-8808, SJIF 2018 = 6.371, www.srjis.com PEER REVIEWED JOURNAL, NOV-DEC, 2018, VOL- 6/48 JAAT-RAJPOOT RULERS AND THE ARCHITECTURE OF DEEG PALACE RAJASTHAN Y N Tripathi1, Ph.D, & Sudeepmala2 1 Associate Professor, Department of History, AGRA COLLEGE AGRA 2 Research Scholar, Department of History, AGRA COLLEGE AGRA E-mail: [email protected] *Corresponding Author Y N Tripathi, Ph.D. Associate Professor, Department of History, AGRA COLLEGE AGRA Abstract Bharatpur in Rajasthan is known for its Jat glorious kings and their kingdoms who ruled the tiny State till recently. Deeg is a 32 kms away town which came into glory much earlier and is privileged to have a huge royal palace which was beautifully managed and partly inhabited by its legitimate inheritors till the year 1970. Deeg had been the pride of the Jat rulers of the time. Deeg Palace is a living testimony to the Jat rulers who fought bravely with the Mughals and Marathas onslaught. In a historical battle, 80,000 odd two armies were battered by the local army led by Raja Suraj Mal. When Raja Suraj Mal moved to Bharatpur, and made it his Capital, it relegated to the second place of the kingdom. Few historians are of the view that most of the stone used was looted from Mughal buildings and made use of in Deeg Palace after their victory. Since Bharatpur and Agra were the nearest places, the developments of these places affected the rule and rulers. Feeling jealous and due to political compulsions, the Deeg had been the centre of invasion by various enemy forces time to time. -

Alphabetical Roll of Advocates at Mathura

District Court Mathura Alphabetical Roll Of Advocates At Mathura SI No. Name Of Father’s/ Date Of Birth Enrolm Date of Complete Address Telephone No. E.Mail Remarks Advocates Husband Name ent enrolment I.D. no./year Residence with P.S. Office Residence Mobile / Council 1 Ashok Kumar Shri Babu lal 15-07-1962 11306/ 03-10-1999 Gali no. 6//2 B Block 9458808845 99 janakpuri maholi road Ps-Kotwali mathura 2 Amit Kumar Late Iqbal 01-05-1976 10067/ 31-12-2009 Radha niwas Vrindavan 9712961636 Singh singh 09 Ps-vrindavan Mathura 3 Arvind Kumar Shri R.K. 25-08-1953 D407/8 13-09- 15/51 Padampuri Sonkh 9758933826 Gautam Gautam 4 1984` Road Ps-haiway Mathura 4 Ashok Saxena Devendra 30-06-1986 987/11 10-02-2011 67 Sadar Bazar Ps-sadar 9759776655 Saxena Mathura 5 Anil Kumar Mohan Lal 13-12-1970 36220/ 31-03-1996 3A/151 Krishna Bihar 9412828774 96 colony B.S.A. College to Radika Bihar Road Ps- kotwali Mathura 6 Arit saxena Devendra 23.10-1984 8014/1 30-11-2014 67 sadar bazar Ps-sadar 9897375479 saxena 4 mathura 7 Arvind Kumar Shri shubh 23-03-1976 7868/2 09-08-2003 831 Upper lane anta 9219568042 sharma kirti shrma 003 padsa Ps-kotwali mathura 8 Ashok Kumar Baldev singh 03-11-1976 02533/ 13-02-2010 397 Laxmi nagar 8534805966 10 jamunapar Ps-jamunapar mathura 9 Amit kumar Mathuresh 31-08-1989 10163/ 05-12-2012 Thok kamal sonai ps- 9411253664 kumar 12 raya mathura 10 Anil Kumar Ram pal singh 13-03-1979 6954/0 30-11-2008 39 sanjay nagar krishna 8533090958 8 nagar Ps-kotwali mathura 11 Asha rani Late ram nath 08-09-1960 10294/ 18-10-2003 Imli vali gali gopeswar -

137211 List.Xlsx

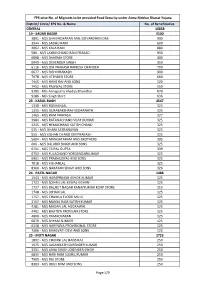

FPS‐wise No. of Migrants to be provided Food Security under Atma Nirbhar Bharat Yojana District/ Circle/ FPS No. & Name No. of Beneficiaries CENTRAL 16858 19 ‐ SADAR BAZAR 9100 3891 ‐ M/S SHAIVACHARAN MAL GOVARDHAN DAS 900 3944 ‐ M/S SADHU RAM 600 4062 ‐ M/S KALA RAM 880 580 ‐ M/S LAXMI CHAND RAM PRASAD 930 6008 ‐ M/S SHARMA STORE 400 6049 ‐ M/S DEVENDER SINGH 950 6116 ‐ M/S OM PRAKASH RAMESH CHANDER 700 6677 ‐ M/S RISHI PRAKASH 900 7078 ‐ M/S JITENDER STORE 664 7445 ‐ M/S HANS RAJ AND SONS 120 7452 ‐ M/S PALIWAL STORE 550 9285 ‐ M/s Annapurna khadya Bhandhar 870 9286 ‐ M/s Singh Store 636 23 ‐ KAROL BAGH 4547 1330 ‐ M/S ROSHANLAL 325 1355 ‐ M/S GURABAKSHRAY KEDARNATH 325 1465 ‐ M/S RAM PRAKASH 327 3984 ‐ M/S RATANACHAND VIJAY KUMAR 325 4245 ‐ M/S HEMACHAND SATISH CHAND 325 535 ‐ M/S DHANI SATRANAYAN 325 555 ‐ M/S KISHAN CHAND OM PRAKASH 325 5604 ‐ M/S MANGATARAM AND BROTHERS 305 606 ‐ M/S DALABIR SINGH AND SONS 325 6741 ‐ M/S TEJPAL GUPTA 339 6753 ‐ M/S FULACHAND YOEGENDARKUMAR 325 6961 ‐ M/S PRABHUDYAL AND SONS 325 7018 ‐ M/S KISHANLAL 325 8360 ‐ M/S NARAYAN SINGH AND SONS 326 24 ‐ PATEL NAGAR 1488 1543 ‐ M/S HARAPRKASH ASHOK KUMAR 125 1722 ‐ M/S SOHAN LAL KEWAL KISHAN 125 1727 ‐ M/S BALJEET NAGAR KANAJYUMAR KOAP STORE 113 1748 ‐ M/S JOHARI LAL 125 1757 ‐ M/S CHAWLA FLOOR MILLS 125 3167 ‐ M/S MANSA RAM SATISH KUMAR 125 4281 ‐ M/S MADAN LAL AGGRAWAL 125 4401 ‐ M/S BHATIYA PROVIJAN STORE 125 4800 ‐ M/S RAMACHARAN 125 6070 ‐ M/S SHYAM SUNDER 125 6438 ‐ M/S HARIYANA PROVISIONAL STORE 125 7306 ‐ M/S BHAGVATI DEVI AND SONS 125 25 ‐ MOTI NAGAR 1723 1892 ‐ M/S CHUNNI LAL HANS RAJ 250 1975 ‐ M/S JAGANNATH SURENDER KUMAR 250 3331 ‐ M/S ASHA SINGH JOGINDER SINGH 250 6835 ‐ M/S HARI RAM SUSHIL KUMAR 250 7905 ‐ M/S RAJ STORE 250 8303 ‐ M/S UDEY RAM AND SONS 250 Page:1/9 District/ Circle/ FPS No. -

History of Bharatpur

Bharatpur, Rajasthan This article is about the municipality in Rajasthan, India. For its namesake district, see Bharatpur district . For other uses, see Bharatpur (disambiguation) . Bharatpur भरतपुर city Bharatpur Location in Rajasthan, India Coordinates: 27.22°N 77.48°E Coordinates : 27.22°N 77.48°E Country India State Rajasthan District Bharatpur Elevation 183 m (600 ft) Population (2011) • Total 252,109 Languages • Official Hindi Time zone IST (UTC+5:30 ) PIN 321001 Area code(s) (+91) 5644 Vehicle registration RJ 05 Website www.bharatpur.rajasthan.gov.in Flag of Bharatpur State Bharatpur is a city and newly created municipal corporation in the Indian state of Rajasthan . Located in the Brij region, Bharatpur was once considered to be impregnable. The city is situated 180 kilometres (110 mi) south of India's capital, New Delhi, 178 kilometres (111 mi) from Pink City Jaipur , 55 kilometres (34 mi) west of Agra and 35 kilometres (22 mi) from Krishna 's birthplace at Mathura . It is also the administrative headquarters of Bharatpur District and the headquarters of Bharatpur Division of Rajasthan. The Royal House of Bharatpur traces its history to the 11th century. Recently Bharatpur has been included in Delhi's National Capital Region (NCR). [1] The city has an average elevation of 183 metres (600 ft) and is also known as "Lohagarh" and the "Eastern Gateway to Rajasthan". [2] It is famous for Keoladeo National Park ( A UNESCO's World Heritage Site). Bharatpur lies on the Golden Tourism Triangle of Delhi–Jaipur–Agra and hence a large number of national and international tourists visit Bharatpur every year.