Griffith Review, 2017; 55:135-159

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Indigenous Design Issuesceduna Aboriginal Children and Family

INDIGENOUS DESIGN ISSUES: CEDUNA ABORIGINAL CHILDREN AND FAMILY CENTRE ___________________________________________________________________________________ 1 INDIGENOUS DESIGN ISSUES: CEDUNA ABORIGINAL CHILDREN AND FAMILY CENTRE ___________________________________________________________________________________ 2 INDIGENOUS DESIGN ISSUES: CEDUNA ABORIGINAL CHILDREN AND FAMILY CENTRE ___________________________________________________________________________________ TABLE OF CONTENTS PREFACE .................................................................................................................................... 5 ACKNOWELDGEMENTS............................................................................................................ 5 INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 5 PART 1: PRECEDENTS AND “BEST PRACTICE„ DESIGN ....................................................10 The Design of Early Learning, Child-care and Children and Family Centres for Aboriginal People ..................................................................................................................................10 Conceptions of Quality ........................................................................................................ 10 Precedents: Pre-Schools, Kindergartens, Child and Family Centres ..................................12 Kulai Aboriginal Preschool ............................................................................................. -

Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla Grammar This Book Is Available As a Free Fully-Searchable Ebook from Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla Grammar

Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla grammar This book is available as a free fully-searchable ebook from www.adelaide.edu.au/press Clamor Schürmann's Barngarla grammar A commentary on the first section of A vocabulary of the Parnkalla language (revised edition 2018) by Mark Clendon Linguistics Department, Faculty of Arts The University of Adelaide Clamor Wilhelm Schürmann Published in Adelaide by University of Adelaide Press The University of Adelaide Level 14, 115 Grenfell Street South Australia 5005 [email protected] www.adelaide.edu.au/press The University of Adelaide Press publishes externally refereed scholarly books by staff of the University of Adelaide. It aims to maximise access to the University’s best research by publishing works through the internet as free downloads and for sale as high quality printed volumes. © 2015 Mark Clendon, 2018 for this revised edition This work is licenced under the Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial- NoDerivatives 4.0 International (CC BY-NC-ND 4.0) License. To view a copy of this licence, visit http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-nd/4.0 or send a letter to Creative Commons, 444 Castro Street, Suite 900, Mountain View, California, 94041, USA. This licence allows for the copying, distribution, display and performance of this work for non-commercial purposes providing the work is clearly attributed to the copyright holders. Address all inquiries to the Director at the above address. For the full Cataloguing-in-Publication data please contact the National Library of Australia: [email protected] -

Introduction

This item is Chapter 1 of Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus Editors: Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson ISBN 978-0-728-60406-3 http://www.elpublishing.org/book/language-land-and-song Introduction Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson Cite this item: Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson (2016). Introduction. In Language, land & song: Studies in honour of Luise Hercus, edited by Peter K. Austin, Harold Koch & Jane Simpson. London: EL Publishing. pp. 1-22 Link to this item: http://www.elpublishing.org/PID/2001 __________________________________________________ This electronic version first published: March 2017 © 2016 Harold Koch, Peter Austin and Jane Simpson ______________________________________________________ EL Publishing Open access, peer-reviewed electronic and print journals, multimedia, and monographs on documentation and support of endangered languages, including theory and practice of language documentation, language description, sociolinguistics, language policy, and language revitalisation. For more EL Publishing items, see http://www.elpublishing.org 1 Introduction Harold Koch,1 Peter K. Austin 2 & Jane Simpson 1 Australian National University1 & SOAS University of London 2 1. Introduction Language, land and song are closely entwined for most pre-industrial societies, whether the fishing and farming economies of Homeric Greece, or the raiding, mercenary and farming economies of the Norse, or the hunter- gatherer economies of Australia. Documenting a language is now seen as incomplete unless documenting place, story and song forms part of it. This book presents language documentation in its broadest sense in the Australian context, also giving a view of the documentation of Australian Aboriginal languages over time.1 In doing so, we celebrate the achievements of a pioneer in this field, Luise Hercus, who has documented languages, land, song and story in Australia over more than fifty years. -

Coober Pedy, South Australia

The etymology of Coober Pedy, South Australia Petter Naessan The aim of this paper is to outline and assess the diverging etymologies of ‘Coober Pedy’ in northern South Australia, in the search for original and post-contact local Indigenous significance associated with the name and the region. At the interface of contemporary Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara opinion (mainly in the Coober Pedy region, where I have conducted fieldwork since 1999) and other sources, an interesting picture emerges: in the current use by Yankunytjatjara and Pitjantjatjara people as well as non-Indigenous people in Coober Pedy, the name ‘Coober Pedy’ – as ‘white man’s hole (in the ground)’ – does not seem to reflect or point toward a pre-contact Indigenous presence. Coober Pedy is an opal mining and tourist town with a total population of about 3500, situated near the Stuart Highway, about 850 kilometres north of Adelaide, South Australia. Coober Pedy is close to the Stuart Range, lies within the Arckaringa Basin and is near the border of the Great Victoria Desert. Low spinifex grasslands amounts for most of the sparse vegetation. The Coober Pedy and Oodnadatta region is characterised by dwarf shrubland and tussock grassland. Further north and northwest, low open shrub savanna and open shrub woodland dominates.1 Coober Pedy and surrounding regions are arid and exhibit very unpredictable rainfall. Much of the economic activity in the region (as well as the initial settlement of Euro-Australian invaders) is directly related to the geology, namely quite large deposits of opal. The area was only settled by non-Indigenous people after 1915 when opal was uncovered but traditionally the Indigenous population was western Arabana (Midlaliri). -

Aboriginal Agency, Institutionalisation and Survival

2q' t '9à ABORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND PEGGY BROCK B. A. (Hons) Universit¡r of Adelaide Thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in History/Geography, University of Adelaide March f99f ll TAT}LE OF CONTENTS ii LIST OF TAE}LES AND MAPS iii SUMMARY iv ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS . vii ABBREVIATIONS ix C}IAPTER ONE. INTRODUCTION I CFIAPTER TWO. TI{E HISTORICAL CONTEXT IN SOUTH AUSTRALIA 32 CHAPTER THREE. POONINDIE: HOME AWAY FROM COUNTRY 46 POONINDIE: AN trSTä,TILISHED COMMUNITY AND ITS DESTRUCTION 83 KOONIBBA: REFUGE FOR TI{E PEOPLE OF THE VI/EST COAST r22 CFIAPTER SIX. KOONIBBA: INSTITUTIONAL UPHtrAVAL AND ADJUSTMENT t70 C}IAPTER SEVEN. DISPERSAL OF KOONIBBA PEOPLE AND THE END OF TI{E MISSION ERA T98 CTIAPTER EIGHT. SURVTVAL WITHOUT INSTITUTIONALISATION236 C}IAPTER NINtr. NEPABUNNA: THtr MISSION FACTOR 268 CFIAPTER TEN. AE}ORIGINAL AGENCY, INSTITUTIONALISATION AND SURVTVAL 299 BIBLIOGRAPI{Y 320 ltt TABLES AND MAPS Table I L7 Table 2 128 Poonindie location map opposite 54 Poonindie land tenure map f 876 opposite 114 Poonindie land tenure map f 896 opposite r14 Koonibba location map opposite L27 Location of Adnyamathanha campsites in relation to pastoral station homesteads opposite 252 Map of North Flinders Ranges I93O opposite 269 lv SUMMARY The institutionalisation of Aborigines on missions and government stations has dominated Aboriginal-non-Aboriginal relations. Institutionalisation of Aborigines, under the guise of assimilation and protection policies, was only abandoned in.the lg7Os. It is therefore important to understand the implications of these policies for Aborigines and Australian society in general. I investigate the affect of institutionalisation on Aborigines, questioning the assumption tl.at they were passive victims forced onto missions and government stations and kept there as virtual prisoners. -

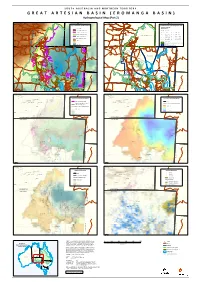

GREAT ARTESIAN BASIN Responsibility to Any Person Using the Information Or Advice Contained Herein

S O U T H A U S T R A L I A A N D N O R T H E R N T E R R I T O R Y G R E A T A R T E S I A N B A S I N ( E RNturiyNaturiyaO M A N G A B A S I N ) Pmara JutPumntaara Jutunta YuenduYmuuendumuYuelamu " " Y"uelamu Hydrogeological Map (Part " 2) Nyirri"pi " " Papunya Papunya ! Mount Liebig " Mount Liebig " " " Haasts Bluff Haasts Bluff ! " Ground Elevation & Aquifer Conditions " Groundwater Salinity & Management Zones ! ! !! GAB Wells and Springs Amoonguna ! Amoonguna " GAB Spring " ! ! ! Salinity (μ S/cm) Hermannsburg Hermannsburg ! " " ! Areyonga GAB Spring Exclusion Zone Areyonga ! Well D Spring " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " Wallace Rockhole Santa Teresa " " " " Extent of Saturated Aquifer ! D 1 - 500 ! D 5001 - 7000 Extent of Confined Aquifer ! D 501 - 1000 ! D 7001 - 10000 Titjikala Titjikala " " NT GAB Management Zone ! D ! Extent of Artesian Water 1001 - 1500 D 10001 - 25000 ! D ! Land Surface Elevation (m AHD) 1501 - 2000 D 25001 - 50000 Imanpa Imanpa ! " " ! ! D 2001 - 3000 ! ! 50001 - 100000 High : 1515 ! Mutitjulu Mutitjulu ! ! D " " ! 3001 - 5000 ! ! ! Finke Finke ! ! ! " !"!!! ! Northern Territory GAB Water Control District ! ! ! Low : -15 ! ! ! ! ! ! ! FNWAP Management Zone NORTHERN TERRITORY Birdsville NORTHERN TERRITORY ! ! ! Birdsville " ! ! ! " ! ! SOUTH AUSTRALIA SOUTH AUSTRALIA ! ! ! ! ! ! !!!!!!! !!!! D !! D !!! DD ! DD ! !D ! ! DD !! D !! !D !! D !! D ! D ! D ! D ! D ! !! D ! D ! D ! D ! DDDD ! Western D !! ! ! ! ! Recharge Zone ! ! ! ! ! ! D D ! ! ! ! ! ! N N ! ! A A ! L L ! ! ! ! S S ! ! N N ! ! Western Zone E -

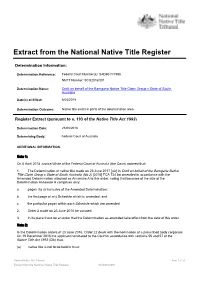

Extract from the National Native Title Register

Extract from the National Native Title Register Determination Information: Determination Reference: Federal Court Number(s): SAD6011/1998 NNTT Number: SCD2016/001 Determination Name: Croft on behalf of the Barngarla Native Title Claim Group v State of South Australia Date(s) of Effect: 6/04/2018 Determination Outcome: Native title exists in parts of the determination area Register Extract (pursuant to s. 193 of the Native Title Act 1993) Determination Date: 23/06/2016 Determining Body: Federal Court of Australia ADDITIONAL INFORMATION: Note 1: On 6 April 2018 Justice White of the Federal Court of Australia (the Court) ordered that: 1. The Determination of native title made on 23 June 2017 [sic] in Croft on behalf of the Barngarla Native Title Claim Group v State of South Australia (No 2) [2016] FCA 724 be amended in accordance with the Amended Determination attached as Annexure A to this order, noting that because of the size of the Determination Annexure A comprises only: a. pages i to xv inclusive of the Amended Determination; b. the first page of any Schedule which is amended; and c. the particular pages within each Schedule which are amended. 2. Order 2 made on 23 June 2016 be vacated. 3. In its place there be an order that the Determination as amended take effect from the date of this order. Note 2: In the Determination orders of 23 June 2016, Order 22 deals with the nomination of a prescribed body corporate. On 19 December 2016 the applicant nominated to the Court in accordance with sections 56 and 57 of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth) that: (a) native title is not to be held in trust; National Native Title Tribunal Page 1 of 20 Extract from the National Native Title Register SCD2016/001 and, accordingly, pursuant to Order 22(b) of 23 June 2016: (b) the Barngarla Determination Aboriginal Corporation is nominated as the prescribed body corporate for the purpose of section 57(2) of the Native Title Act 1993 (Cth). -

Lake Torrens SA 2016, a Bush Blitz Survey Report

Lake Torrens South Australia 28 August–9 September 2016 Bush Blitz Species Discovery Program Lake Torrens, South Australia 28 August–9 September 2016 What is Bush Blitz? Bush Blitz is a multi-million dollar partnership between the Australian Government, BHP Billiton Sustainable Communities and Earthwatch Australia to document plants and animals in selected properties across Australia. This innovative partnership harnesses the expertise of many of Australia’s top scientists from museums, herbaria, universities, and other institutions and organisations across the country. Abbreviations ABRS Australian Biological Resources Study AD State Herbarium of South Australia ANIC Australian National Insect Collection CSIRO Commonwealth Scientific and Industrial Research Organisation DEWNR Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources (South Australia) DSITI Department of Science, Information Technology and Innovation (Queensland) EPBC Act Environment Protection and Biodiversity Conservation Act 1999 (Commonwealth) MEL National Herbarium of Victoria NPW Act National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 (South Australia) RBGV Royal Botanic Gardens Victoria SAM South Australian Museum Page 2 of 36 Lake Torrens, South Australia 28 August–9 September 2016 Summary In late August and early September 2016, a Bush Blitz survey was conducted in central South Australia at Lake Torrens National Park (managed by SA Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources) and five adjoining pastoral stations to the west (Andamooka, Bosworth, Pernatty, Purple Downs and Roxby Downs). The traditional owners of this country are the Kokatha people and they were involved with planning and preparation of the survey and accompanied survey teams during the expedition itself. Lake Torrens National Park and surrounding areas have an arid climate and are dominated by three land systems: Torrens (bed of Lake Torrens), Roxby (dunefields) and Arcoona (gibber plains). -

Southern Eyre Subregional Description

Southern Eyre Subregional Description Landscape Plan for Eyre Peninsula - Appendix C Southern Eyre comprises a land area of around 6,500 square kilometres, along with a large marine area. The southern boundary extends east from Spencer Gulf to the Southern Ocean, while the northern boundary extends along the agricultural plains north of Cummins. QUICK STATS Population: Approximately 23,500 Major towns (population): Port Lincoln (16,000), Tumby Bay (1,474), Cummins (719), Coffin Bay (615) Traditional Owners: Barngarla and Nauo nations Local Governments: Port Lincoln City Council, District Council of Lower Eyre Peninsula and District Council of Tumby Bay Land Area: Approximately 6,500 square kilometres Main land uses (% of land area): Cropping and grazing (63%), conservation (34%) Main industries: Fishing, aquaculture, agriculture, retail trade, health and community services, tourism, construction, mining Annual Rainfall: 340 – 560mm Highest elevation: Marble Range (436 metres AHD) Coastline length: 710 kilometres (excludes islands) Number of Islands: 113 2 Southern Eyre Subregional Description Southern Eyre What’s valued in Southern Eyre enjoy camping, 4WD adventures and walking. The pristine environment at Memory Cove and Coffin The Southern Eyre community is intrinsically linked Bay’s remoteness and wildness, provide a sense of to the natural environment with its identity ingrained adventure and place. in the “great outdoors”. Many people have their own favourite spot where they go to unwind and feel a Sir Joseph Banks Group are magic sense of place. For some it is their own patch, for parts of the world. They have an others it is a secluded beach or an adventure in the abundance of marine and birdlife bush. -

Northern Flinders Ranges Fire Management Plan 2016

Northern Flinders Ranges Fire Management Plan 2016 Incorporating: Ikara-Flinders Ranges National Park, Vulkathunha-Gammon Ranges National Park, Ediacara Conservation Park, Bunkers Conservation Reserve and included Crown lands and participating Heritage Agreements Ikara-Flinders Ranges National Park Co-Management Board Vulkathunha-Gammon Ranges National Park Co-Management Board For further information please contact: Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources Phone Information Line (08) 8204 1910, or see SA White Pages for your local Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources office. This Fire Management Plan is also available from: www.environment.sa.gov.au/fire/ Front Cover: Ikara (Wilpena Pound) by DEWNR Permissive Licence © State of South Australia through the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Apart from fair dealings and other uses permitted by the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth), no part of this publication may be reproduced, published, communicated, transmitted, modified or commercialised without the prior written approval of the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources. Written requests for permission should be addressed to: Communications Manager Communications and Community Engagement Branch Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources GPO Box 1047 Adelaide SA 5001 Disclaimer While reasonable efforts have been made to ensure the contents of this publication are factually correct , the Department of Environment, Water and Natural Resources makes no representations and accepts no responsibility for the accuracy, completeness or fitness for any particular purpose of the contents, and shall not be liable for any loss or damage that may be occasioned directly or indirectly through the use of or reliance on the contents of this publication. -

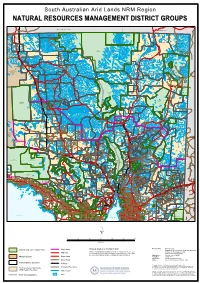

Natural Resources Management District Groups

South Australian Arid Lands NRM Region NNAATTUURRAALL RREESSOOUURRCCEESS MMAANNAAGGEEMMEENNTT DDIISSTTRRIICCTT GGRROOUUPPSS NORTHERN TERRITORY QUEENSLAND Mount Dare H.S. CROWN POINT Pandie Pandie HS AYERS SIMPSON DESERT RANGE SOUTH Tieyon H.S. CONSERVATION PARK ALTON DOWNS TIEYON WITJIRA NATIONAL PARK PANDIE PANDIE CORDILLO DOWNS HAMILTON DEROSE HILL Hamilton H.S. SIMPSON DESERT KENMORE REGIONAL RESERVE Cordillo Downs HS PARK Lambina H.S. Mount Sarah H.S. MOUNT Granite Downs H.S. SARAH Indulkana LAMBINA Todmorden H.S. MACUMBA CLIFTON HILLS GRANITE DOWNS TODMORDEN COONGIE LAKES Marla NATIONAL PARK Mintabie EVERARD PARK Welbourn Hill H.S. WELBOURN HILL Marla - Oodnadatta INNAMINCKA ANANGU COWARIE REGIONAL PITJANTJATJARAKU Oodnadatta RESERVE ABORIGINAL LAND ALLANDALE Marree - Innamincka Wintinna HS WINTINNA KALAMURINA Innamincka ARCKARINGA Algebuckinna Arckaringa HS MUNGERANIE EVELYN Mungeranie HS DOWNS GIDGEALPA THE PEAKE Moomba Evelyn Downs HS Mount Barry HS MOUNT BARRY Mulka HS NILPINNA MULKA LAKE EYRE NATIONAL MOUNT WILLOUGHBY Nilpinna HS PARK MERTY MERTY Etadunna HS STRZELECKI ELLIOT PRICE REGIONAL CONSERVATION ETADUNNA TALLARINGA PARK RESERVE CONSERVATION Mount Clarence HS PARK COOBER PEDY COMMONAGE William Creek BOLLARDS LAGOON Coober Pedy ANNA CREEK Dulkaninna HS MABEL CREEK DULKANINNA MOUNT CLARENCE Lindon HS Muloorina HS LINDON MULOORINA CLAYTON Curdimurka MURNPEOWIE INGOMAR FINNISS STUARTS CREEK SPRINGS MARREE ABORIGINAL Ingomar HS LAND CALLANNA Marree MUNDOWDNA LAKE CALLABONNA COMMONWEALTH HILL FOSSIL MCDOUAL RESERVE PEAK Mobella -

Annual Report 2006–2007

06 07 NATIONAL NATIVE TITLE TRIBUNAL CONTACT DETAILS Annual Report 2006–2007 Tribunal National Native Title PRINCIPAL REGISTRY (PERTH) SOUTH AUSTRALIA 4th Floor, Commonwealth Law Courts Building Level 10, Chesser House 1 Victoria Avenue 91 Grenfell Street Perth WA 6000 Adelaide SA 5000 GPO Box 9973, Perth WA 6848 GPO Box 9973, Adelaide SA 5001 Telephone: (08) 9268 7272 Telephone: (08) 8306 1230 Facsimile: (08) 9268 7299 Facsimile: (08) 8224 0939 NEW SOUTH WALES AND AUSTRALIAN VICTORIA AND TASMANIA CAPITAL TERRITORY Level 8 Level 25 310 King Street Annual Report 25 Bligh Street Melbourne Vic. 3000 Sydney NSW 2000 GPO Box 9973, Melbourne Vic. 3001 GPO Box 9973, Sydney NSW 2001 Telephone: (03) 9920 3000 2006–2007 Telephone: (02) 9235 6300 Facsimile: (03) 9606 0680 Facsimile: (02) 9233 5613 WESTERN AUSTRALIA NORTHERN TERRITORY 11th Floor, East Point Plaza 5th Floor, NT House 233 Adelaide Terrace 22 Mitchell Street Perth WA 6000 Darwin NT 0800 GPO Box 9973, Perth WA 6848 GPO Box 9973, Darwin NT 0801 Telephone: (08) 9268 9700 Telephone: (08) 8936 1600 Facsimile: (08) 9221 7158 Facsimile: (08) 8981 7982 NATIONAL FREECALL NUMBER 1800 640 501 QUEENSLAND Level 30 WEBSITE: www.nntt.gov.au 239 George Street Brisbane Qld 4000 National Native Title Tribunal office hours GPO Box 9973, Brisbane Qld 4001 8.30am – 5.00pm 8.00am – 4.30pm (Northern Territory) Telephone: (07) 3226 8200 Facsimile: (07) 3226 8235 The Tribunal welcomes feedback on whether this information was useful. QUEENSLANd – CAIRNS (REGIONAL OFFICE) Email Public Affairs with your comments Level 14, Cairns Corporate Tower and suggestions to [email protected] 15 Lake Street or telephone 08 9268 7495.