Follies' Shows It, Too, Is Still Here

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

July 8-18, 2021

July 8-18, 2021 Val Underwood Artistic Director ExecutiveFrom Directorthe Dear Friends: to offer a world-class training and performance program, to improve Throughout education, and to elevate the spirit of history, global all who participate. pandemics have shaped society, We are delighted to begin our season culture, and with Stars of Tomorrow, featuring institutions. As many successful young alumni of our we find ourselves Young Singer Program—including exiting the Becca Barrett, Stacee Firestone, and COVID-19 crisis, one pandemic and many others. Under the direction subsequent recovery that comes to of both Beth Dunnington and Val mind is the bubonic plague—or Black Underwood, this performance will Death—which devastated Europe and celebrate the art of storytelling in its Asia in the 14th century. There was a most simple and elegant state. The silver lining, however, as it’s believed season also includes performances that the socio-economic impacts of by many of our very own, long- the Plague on European society— time Festival favorites, and two of particularly in Italy—helped create Broadway’s finest, including HPAF the conditions necessary for what is Alumna and 1st Place Winner of arguably the greatest post-pandemic the 2020 HPAF Musical Theatre recovery of all time—the Renaissance. Competition, Nyla Watson (Wicked, The Color Purple). Though our 2021 Summer Festival is not what was initially envisioned, As we enter the recovery phase and we are thrilled to return to in-person many of us eagerly await a return to programming for the first time in 24 “normal,” let’s remember one thing: we months. -

View the 2019 Conductors Guild NYC Conference Program Booklet!

The World´s Only Manufacturer of the Celesta CELESTA ACTION The sound plate is placed above a wooden resonator By pressing the key the felt hammer is set in moti on The felt hammer strikes the sound plate from above CELESTA MODELS: 3 ½ octave (f1-c5) 4 octave (c1-c5) 5 octave (c-c5) 5 ½ octave Compact model (c-f5) 5 ½ octave Studio model (c-f5) (Cabinet available in natural or black oak - other colors on request) OTHER PRODUCTS: Built-in Celesta/Glockenspiel for Pipe Organs Keyboard Glockenspiel „Papageno“ (c2-g5) NEW: The Bellesta: Concert Glockenspiel 5½ octave Compact model, natural oak with wooden resonators (c2-e5) SERVICES: worldwide delivery, rental, maintenance, repair and overhaul Schiedmayer Celesta GmbH Phone Tel. +49 (0)7024 / 5019840 Schäferhauser Str. 10/2 [email protected] 73240 Wendlingen/Germany www.celesta-schiedmayer.de President's Welcome Dear Friends and Colleagues, Welcome to New York City! My fellow officers, directors, and I would like to welcome you to the 2019 Conductors Guild National Conference. Any event in New York City is bound to be an exciting experience, and this year’s conference promises to be one you won’t forget. We began our conference with visits to the Metropolitan Opera for a rehearsal and backstage tour, and then we were off to the Juilliard School to see some of their outstanding manuscripts and rare music collection! Our session presenters will share helpful information, insightful and inspiring thoughts, and memories of one of the 20th Century’s greatest composers and conductors, Pierre Boulez. And, what would a New York event be without a little Broadway, and Ballet? An event such as this requires dedication and work from a committed planning committee. -

Audience Insights Table of Contents

GOODSPEED MUSICALS AUDIENCE INSIGHTS TABLE OF CONTENTS JUNE 29 - SEPT 8, 2018 THE GOODSPEED Production History.................................................................................................................................................................................3 Synopsis.......................................................................................................................................................................................................4 Characters......................................................................................................................................................................................................5 Meet the Writer........................................................................................................................................................................................6 Meet the Creative Team.......................................................................................................................................................................7 Director's Vision......................................................................................................................................................................................8 The Kids Company of Oliver!............................................................................................................................................................10 Dickens and the Poor..........................................................................................................................................................................11 -

The Maple Shade Arts Council Summer Theatre the MAPLE SHADE Announces Our Summer Children's Show ARTS COUNCIL Once Upon a Mattress PROUDLY PRESENTS

The Maple Shade Arts Council Summer Theatre THE MAPLE SHADE announces our summer children's show ARTS COUNCIL Once Upon A Mattress PROUDLY PRESENTS PERFORMANCES: August 6 @ 7:30PM August 7 @ 7:30PM August 8 @ 2:00PM and 7:30PM Tickets: $10—adults $8—children/senior citizens Visit www.msartscouncil.org to purchase tickets today! For more information about the Summer Theatre program and how to register for next year, email [email protected] Bring in your playbill or ticket to July 10, 11, 12, 17, 18, 19 @ 7:30PM 114-116 E. MAIN ST. receive a 15% discount off your Maple Shade High School MAPLE SHADE, NJ 08052 bill. Valid before or after the (856)779-8003 performances on July 10-12 and Auditorium 17-19. Not valid with any other coupons, offers, or discounts. 2014 Sponsors OUR MISSION STATEMENT The Maple Shade Arts Council wishes to express our sincere gratitude to the many sponsors to our organization. The Maple Shade Arts Council is a non-profit organization We appreciate your support of the Arts Council. comprised of educators, parents, and community members whose objective is to provide artistic programs and events that will be entertaining, educational, and inspirational for the community. The Arts Council's programming emphasizes theatrical productions and workshops, yet also includes programming for the fine and performing arts. Maple Shade Arts Council Executive Board 2014 President Michael Melvin Vice President Jillian Starr-Renbjor Secretary AnnMarie Underwood Treasurer Matthew Maerten Publicity Director Rose Young Fundraising Director Debra Kleine Fine Arts Director Nancy Haddon *ALL CONCESSIONS WILL BE SOLD PRIOR TO THE SHOW BETWEEN 6:45PM-7:25PM—THERE WILL ONLY BE A BRIEF 10 MINUTE BATHROOM/SNACK BREAK AT INTERMISSION. -

KS5 Exploring Performance Styles in Musical Theatre

Exploring performance KS5 styles in Musical Theatre Heidi McEntee Heidi McEntee is a Dance and KS5 – BTEC LEVEL 3, UNIT D10 Performing Arts specialist based in the Midlands. She has worked in education for over fifteen years delivering a variety of Dance and Performing Arts qualifications at Introduction Levels 1, 2 and 3. She is a Senior Unit D10: Exploring Performance Styles is one of the three units which sit within Module D: Assessment Associate working on musical theatre Skills Development from the new BTEC Level 3 in Performing Arts Practice Performing Arts qualifications and (musical theatre) qualification. This scheme of work focuses on the first unit which introduces a contributing author for student and explores different musical theatre styles. revision guides. This unit requires learners to develop their practical skills in dance, acting and singing while furthering their understanding of musical theatre styles. The unit culminates in a performance of two extracts in two different styles of musical theatre as well as a critical review of the stylistic qualities within these extracts. This scheme of work provides a suggested approach to six weeks of introductory classes, as a part of a full timetable, which explores the development of performance styles through the history of musical theatre via practical activities, short projects and research tasks. Learning objectives By the end of this scheme, learners will have: § Investigated the history of musical theatre and the factors which have influenced its development Unit D10: Exploring Performance § Explored the characteristics of different musical theatre styles and how they have developed Styles from BTEC L3 Nationals over time Performing Arts Practice (musical § Applied stylistic conventions to the performance of material theatre) (2019) § Examined professional work through critical analysis. -

Hair for Rent: How the Idioms of Rock 'N' Roll Are Spoken Through the Melodic Language of Two Rock Musicals

HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS A Thesis Presented to The Graduate Faculty of The University of Akron In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Music Eryn Stark August, 2015 HAIR FOR RENT: HOW THE IDIOMS OF ROCK 'N' ROLL ARE SPOKEN THROUGH THE MELODIC LANGUAGE OF TWO ROCK MUSICALS Eryn Stark Thesis Approved: Accepted: _____________________________ _________________________________ Advisor Dean of the College Dr. Nikola Resanovic Dr. Chand Midha _______________________________ _______________________________ Faculty Reader Interim Dean of the Graduate School Dr. Brooks Toliver Dr. Rex Ramsier _______________________________ _______________________________ Department Chair or School Director Date Dr. Ann Usher ii TABLE OF CONTENTS Page LIST OF TABLES ............................................................................................................. iv CHAPTER I. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................1 II. BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY ...............................................................................3 A History of the Rock Musical: Defining A Generation .........................................3 Hair-brained ...............................................................................................12 IndiffeRent .................................................................................................16 III. EDITORIAL METHOD ..............................................................................................20 -

T H E P Ro G

Friday, February 1, 2019 at 8:30 pm m a r Jose Llana g Kimberly Grigsby , Music Director and Piano o Aaron Heick , Reeds r Pete Donovan , Bass P Jon Epcar , Drums e Sean Driscoll , Guitar h Randy Andos , Trombone T Matt Owens , Trumpet Entcho Todorov and Hiroko Taguchi , Violin Chris Cardona , Viola Clarice Jensen , Cello Jaygee Macapugay , Jeigh Madjus , Billy Bustamante , Renée Albulario , Vocals John Clancy , Orchestrator Michael Starobin , Orchestrator Matt Stine, Music Track Editor This evening’s program is approximately 75 minutes long and will be performed without intermission. Please make certain all your electronic devices are switched off. Lead support provided by PGIM, the global investment management businesses of Prudential Financial, Inc. Endowment support provided by Bank of America This performance is made possible in part by the Josie Robertson Fund for Lincoln Center. Steinway Piano The Appel Room Jazz at Lincoln Center’s Frederick P. Rose Hall American Songbook Additional support for Lincoln Center’s American Songbook is provided by Rita J. and Stanley H. Kaplan Family Foundation, The DuBose and Dorothy Heyward Memorial Fund, The Shubert Foundation, Great Performers Circle, Lincoln Center Spotlight, Chairman’s Council, and Friends of Lincoln Center Public support is made possible by the New York State Council on the Arts with the support of Governor Andrew M. Cuomo and the New York State Legislature Nespresso is the Official Coffee of Lincoln Center NewYork-Presbyterian is the Official Hospital of Lincoln Center Artist catering provided by Zabar’s and Zabars.com UPCOMING AMERICAN SONGBOOK EVENTS IN THE APPEL ROOM: Saturday, February 2 at 8:30 pm Rachael & Vilray Wednesday, February 13 at 8:30 pm Nancy And Beth Thursday, February 14 at 8:30 pm St. -

HERRICK GOLDMAN LIGHTING DESIGNER Website: HG Lighting Design Inc

IGHTING ESIGNER HERRICK GOLDMAN L D Website: HG Lighting Design inc. Phone: 917-797-3624 www.HGLightingDesign.com 1460 Broadway 16th floor E-mail: [email protected] New York, NY 10036 Honors & Awards: •2009 LDI Redden Award for Excellence in Theatrical Design •2009 Henry Hewes (formerly American Theatre Wing) Nominee for “Rooms a Rock Romance” •2009 ISES Big Apple award for Best Event Lighting •2010 Live Design Excellence award for Best Theatrical Lighting Design •2011 Henry Hewes Nominee for Joe DiPietro’s “Falling for Eve” Upcoming: Alice in Wonderland Pittsburgh Ballet, Winter ‘17 Selected Experience: •New York Theater (partial). Jason Bishop The New Victory Theater, Fall ‘16 Jasper in Deadland Ryan Scott Oliver/ Brandon Ivie dir. Prospect Theater Company Off-Broadway, NYC March ‘14 50 Shades! the Musical (Parody) Elektra Theatre Off-Broadway, NYC Jan ‘14 Two Point Oh 59 e 59 theatres Off-Broadway, NYC Oct. ‘13 Amigo Duende (Joshua Henry & Luis Salgado) Museo Del Barrio, NYC Oct. ‘12 Myths & Hymns Adam Guettel Prospect Theater co. Off-Broadway, NYC Jan. ‘12 Falling For Eve by Joe Dipietro The York Theater, Off-Broadway NYC July. ‘10 I’ll Be Damned The Vineyard Theater, Off-Broadway NYC June. ‘10 666 The Minetta Lane Theater Off-Broadway, NYC March. ‘10 Loaded Theater Row Off-Broadway, NYC Nov. ‘09 Flamingo Court New World Stages Off-Broadway, NYC June ‘09 Rooms a Rock Romance Directed by Scott Schwartz, New World Stages, NYC March. ‘09 The Who’s Tommy 15th anniversary concert August Wilson Theater, Broadway, NYC Dec. ‘08 Flamingo Court New World Stages Off-Broadway, NYC July ‘08 The Last Starfighter (The musical) Theater @ St. -

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press Contact: Kathy Kahn

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Press contact: Kathy Kahn, [email protected], 510-418-8523 Theater contact: Harriet Schlader, [email protected], 510-531-9597 Woodminster Summer Musicals AUGUST 2015 -- CALENDAR INFORMATION WHAT: The Producers PERFORMED BY: Woodminster Summer Musicals by Producers Associates, Inc. WHERE: Woodminster Amphitheater in Joaquin Miller Park, 3300 Joaquin Miller Road, Oakland WHEN: August 7-16, 2015 PERFORMANCES: August 7, 8, 9, 13, 14, 15, 16 - 8 p.m. TICKETS: 510-531-9597, or www.woodminster.com, $28-$59 (Discounts for children, seniors, groups) PREVIEW PERFORMANCE: August 6, 8 p.m., All tickets $18 at the door. (Since it's a rehearsal, the show may be stopped to solve technical problems.) A New Mel Brooks Musical, Book by Mel Brooks and Thomas Meehan, Music and Lyrics by Mel Brooks, Based on the 1968 Film, Original direction and choreography by Susan Stroman, Produced by arrangement with Music Theatre International. Photo caption: Greg Carlson* as Max Bialystock, Melissa Reinerston as Ulla, and John Tichenor* as Leo Bloom. PRESS RELEASE The Producers Opens August 7 at Woodminster Summer Musicals Stage Musical is Adapted from Mel Brooks' Classic Comedy Film July 20, 2015, Oakland, CA -- Producers Associates, Inc. announces that the 2015 season of Woodminster Summer Musicals will continue with The Producers, the hit Broadway musical based on the 1968 Mel Brooks film of the same name. It will run August 7-16 at Woodminster Amphitheater in Oakland's Joaquin Miller Park, located at 3300 Joaquin Miller Road in the Oakland hills. The Producers tells the story of a down-on-his-luck Broadway producer and his nervous accountant, who together come up with a scheme to make a million dollars (each) by producing the worst flop in Broadway history. -

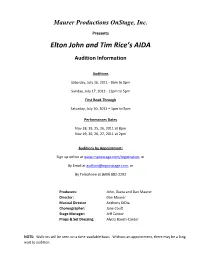

Elton John and Tim Rice's AIDA

Maurer Productions OnStage, Inc. Presents Elton John and Tim Rice’s AIDA Audition Information Auditions Saturday, July 16, 2011 - 9am to 5pm Sunday, July 17, 2011 - 12pm to 5pm First Read-Through Saturday, July 30, 2011 – 1pm to 5pm Performances Dates Nov 18, 19, 25, 26, 2011 at 8pm Nov 19, 20, 26, 27, 2011 at 2pm Auditions by Appointment: Sign up online at www.mponstage.com/registration, or By Email at [email protected], or By Telephone at (609) 882-2292 Producers: John, Diana and Dan Maurer Director: Dan Maurer Musical Director Anthony DiDia Choreographer: Jane Coult Stage Manager: Jeff Cantor Props & Set Dressing: Alycia Bauch-Cantor NOTE: Walk-ins will be seen on a time-available basis. Without an appointment, there may be a long wait to audition. Auditions for Elton John & Tim Rice’s AIDA Index 1. About the Show 2. Available Roles 3. What You Need to Know About the Audition 4. Audition Application 5. Calendar for Conflicts 6. Musical Numbers 7. Audition Monologues 1 Elton John and Tim Rice’s Aida Directed by Dan Maurer Part Broadway musical, part dance spectacular and part rock concert, AIDA is an epic tale about the power and timelessness of love. The show features over twenty roles for singers, dancers, and actors of various races and will be staged by the award winning production team that brought shows like Man of La Mancha and Singin’ in the Rain to Kelsey Theatre. Winner of four Tony Awards when Disney’s Hyperion Theatrical Group first brought it to Broadway, AIDA features music by pop legend Elton John and lyrics by Tim Rice, who wrote the lyrics for hit shows like Jesus Christ Superstar and Evita. -

A Memory of Two Mondays (1955)

Boris Aronson: An Inventory of His Scenic Design Papers at the Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center Descriptive Summary Creator: Aronson, Boris, 1900-1980 Title: Boris Aronson Scenic Design Papers Dates: 1939-1977 Extent: 5 boxes, 4 oversize boxes, 47 oversize folders (4.1 linear feet) Abstract: Russian-born painter, sculptor, and most notably set designer Boris Aronson came to America in 1922. The Scenic Design Papers hold original sketches, prints, photographs, and technical drawings showcasing Aronson's set design work on thirty-one plays written and produced between 1939-1977. RLIN Record #: TXRC00-A6 Language: English. Access: Open for research Administrative Information Acquisition: Gift and purchase, 1996 (G10669, R13821) Processed by: Helen Baer and Toni Alfau, 1999 Repository: Harry Ransom Humanities Research Center, University of Texas at Austin Aronson, Boris, 1900-1980 Biographical Sketch Boris Aronson was born in Kiev in 1900, the son of a Jewish rabbi. He came of age in pre-revolutionary Russia in the city that was at the center of Jewish avant-garde theater. After attending art school in Kiev, Aronson served an apprenticeship with the Constructivist designer Alexandre Exter. Under Exter's tutelage and under the influence of the Russian theater directors Alexander Tairov and Vsevolod Meyerhold, whom Aronson admired, he rejected the fashionable realism of Stanislavski in favor of stylized reality and Constructivism. After his apprenticeship he moved to Moscow and then to Germany, where he published two books in 1922, and on their strength was able to obtain a visa to America. In New York he found work in the Yiddish experimental theater designing sets and costumes for, among other venues, the Unser Theatre and the Yiddish Art Theatre. -

1998 Acquisitions

1998 Acquisitions PAINTINGS PRINTS Carl Rice Embrey, Shells, 1972. Acrylic on panel, 47 7/8 x 71 7/8 in. Albert Belleroche, Rêverie, 1903. Lithograph, image 13 3/4 x Museum purchase with funds from Charline and Red McCombs, 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.5. 1998.3. Henry Caro-Delvaille, Maternité, ca.1905. Lithograph, Ernest Lawson, Harbor in Winter, ca. 1908. Oil on canvas, image 22 x 17 1/4 in. Museum purchase, 1998.6. 24 1/4 x 29 1/2 in. Bequest of Gloria and Dan Oppenheimer, Honoré Daumier, Ne vous y frottez pas (Don’t Meddle With It), 1834. 1998.10. Lithograph, image 13 1/4 x 17 3/4 in. Museum purchase in memory Bill Reily, Variations on a Xuande Bowl, 1959. Oil on canvas, of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.23. 70 1/2 x 54 in. Gift of Maryanne MacGuarin Leeper in memory of Marsden Hartley, Apples in a Basket, 1923. Lithograph, image Blanche and John Palmer Leeper, 1998.21. 13 1/2 x 18 1/2 in. Museum purchase in memory of Alexander J. Kent Rush, Untitled, 1978. Collage with acrylic, charcoal, and Oppenheimer, 1998.24. graphite on panel, 67 x 48 in. Gift of Jane and Arthur Stieren, Maximilian Kurzweil, Der Polster (The Pillow), ca.1903. 1998.9. Woodcut, image 11 1/4 x 10 1/4 in. Gift of Mr. and Mrs. Frederic J. SCULPTURE Oppenheimer in memory of Alexander J. Oppenheimer, 1998.4. Pierre-Jean David d’Angers, Philopoemen, 1837. Gilded bronze, Louis LeGrand, The End, ca.1887. Two etching and aquatints, 19 in.