Coverage of the Vietnam Antiwar Movement in Time and Newsweek, 1965-71

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

UvA-DARE (Digital Academic Repository) ‘Whose Vietnam?’ - ‘Lessons learned’ and the dynamics of memory in American foreign policy after the Vietnam War Beukenhorst, H.B. Publication date 2012 Link to publication Citation for published version (APA): Beukenhorst, H. B. (2012). ‘Whose Vietnam?’ - ‘Lessons learned’ and the dynamics of memory in American foreign policy after the Vietnam War. General rights It is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), other than for strictly personal, individual use, unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Disclaimer/Complaints regulations If you believe that digital publication of certain material infringes any of your rights or (privacy) interests, please let the Library know, stating your reasons. In case of a legitimate complaint, the Library will make the material inaccessible and/or remove it from the website. Please Ask the Library: https://uba.uva.nl/en/contact, or a letter to: Library of the University of Amsterdam, Secretariat, Singel 425, 1012 WP Amsterdam, The Netherlands. You will be contacted as soon as possible. UvA-DARE is a service provided by the library of the University of Amsterdam (https://dare.uva.nl) Download date:02 Oct 2021 Bibliography Primary sources cited (Archival material, government publications, reports, surveys, etc.) ___________________________________________________________ Ronald Reagan Presidential Library (RRPL), Simi Valley, California NSC 1, February 6, 1981: Executive Secretariat, NSC: folder NSC 1, NSC Meeting Files, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library (RRPL). ‘News clippings’, Folder: ‘Central American Speech April 27, 1983 – May 21, 1983’, Box 2: Central American Speech – Exercise reports, Clark, William P.: Files, Ronald Reagan Presidential Library (RRPL). -

PROTEST ACTIVITIES in SOUTHERN UNIVERSITIES, 1965-1972 Except

PROTEST ACTIVITIES IN SOUTHERN UNIVERSITIES, 1965-1972 Except where reference is made to the work of others, the work described in this thesis is my own or was done in collaboration with my advisory committee. This thesis does not include proprietary or classified information. ________________________________________ Kristin Elizabeth Grabarek Certificate of Approval: _________________________ ________________________ Angela Lakwete David Carter, Chair Associate Professor Associate Professor History History _________________________ ________________________ Ruth Crocker Stephen L. McFarland Alumni Professor Acting Dean History Graduate School PROTEST ACTIVITIES IN SOUTHERN UNIVERSITIES, 1965-1972 Kristin E. Grabarek A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of Auburn University in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of History Auburn, Alabama May 11, 2006 PROTEST ACTIVITIES IN SOUTHERN UNIVERSITIES, 1965-1972 Kristin E. Grabarek Permission is granted to Auburn University to make copies of this thesis at its discretion, upon request of individuals or institutions and at their expense. The author reserves all publication rights. ______________________________ Signature of Author May 11, 2006 Date of Graduation iii THESIS ABSTRACT PROTEST ACTIVITIES IN SOUTHERN UNIVERSITIES, 1965-1972 Kristin E. Grabarek Master of History, May 11, 2006 (B.A., Greensboro College, 2003) 162 Typed Pages Directed by Dr. David Carter, Dr. Angela Lakwete, and Dr. Ruth Crocker This thesis examines the existence and character of protest movements in southern universities from the fall of 1965 through the spring of 1972, and offers an explanation for the student dissent in the South in these years while also accounting for its relevance to the study of the anti-Vietnam War and civil rights movements. -

Bonnie and Clyde and the Sixties Bruce Campbell

“Something’s happening here”: Bonnie and Clyde and the Sixties Bruce Campbell Something’s happening here What it is ain’t exactly clear (Buffalo Springfield) It was a tumultuous time; 1967, the Age of Aquarius, the time of Flower Power, free love, and hippies.1 There were “Be-Ins” on both coasts. In the Haight-Ashbury section of San Francisco, there was a celebration called the “Summer of Love,” and a top-ten song advised “if you’re going to San Francisco, be sure to wear some flowers in your hair” (McKenzie). Young people were encouraged to “turn on, tune in, drop out,” and the nation suddenly learned about LSD.2 A generation just coming of age called for “peace and love.” Others wanted quicker, more violent change. Young men were being sent to Vietnam to fight what many considered an unjust war. Figures from the US National Archives show that more than eleven thousand young Americans died in Vietnam in 1967. The next year, the number would rise to more than eighteen thousand. The war was costing taxpayers billions of dollars a year, and each month, thousands of young men were being drafted into military service.3 When there were demonstrations against the draft and the war, protestors were met by police and National Guard troops. Groups like the Weathermen began using bombs to strike at “the system.”4 Blacks seeking equality grew frustrated with the slow progress of Martin Luther King’s nonviolent approach to achieving racial equality. In the summer of 1967, race riots plagued Newark, Detroit, and other cities. -

A New Nation Struggles to Find Its Footing

November 1965 Over 40,000 protesters led by several student activist Progression / Escalation of Anti-War groups surrounded the White House, calling for an end to the war, and Sentiment in the Sixties, 1963-1971 then marched to the Washington Monument. On that same day, President Johnson announced a significant escalation of (Page 1 of 2) U.S. involvement in Indochina, from 120,000 to 400,000 troops. May 1963 February 1966 A group of about 100 veterans attempted to return their The first coordinated Vietnam War protests occur in London and Australia. military awards/decorations to the White House in protest of the war, but These protests are organized by American pacifists during the annual were turned back. remembrance of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombings. In the first major student demonstration against the war hundreds of students March 1966 Anti-war demonstrations were again held around the country march through Times Square in New York City, while another 700 march in and the world, with 20,000 taking part in New York City. San Francisco. Smaller numbers also protest in Boston, Seattle, and Madison, Wisconsin. April 1966 A Gallup poll shows that 59% of Americans believe that sending troops to Vietnam was a mistake. Among the age group of 21-29, 1964 Malcolm X starts speaking out against the war in Vietnam, influencing 71% believe it was a mistake compared to only 48% of those over 50. the views of his followers. May 1966 Another large demonstration, with 10,000 picketers calling for January 1965 One of the first violent acts of protest was the Edmonton aircraft an end to the war, took place outside the White House and the Washington bombing, where 15 of 112 American military aircraft being retrofitted in Monument. -

The Kent State Shootings After Nearly 50 Years

The Kent State Shootings after Nearly 50 Years One Lawyer’s Remembrance Sanford Jay roSen Sanford Jay Rosen was the lead attorney for the dead and wounded students of the May 4, 1970, shootings at Kent State. Rosen came to the case in 1977 as lead counsel for the appeal following the victims’ loss of their cases in federal district court in Ohio. After he won the appeal, the cases were sent back to the district court for retrial. Rosen continues to practice law in San Francisco and is a founding partner at the San Francisco law firm Rosen, Bien, Galvan & Grunfeld, LLP. This piece was written in 2019. To understand my involvement in the Kent State cases, we begin with my father’s mother long before I was born in December 1937. Aida Grudsky was born in the late 1860s in Kiev, Ukraine. In 1905, she fled to America with her husband and two sons from Czarist Russia’s latest oppression of Jews. Neither son survived the journey. Her eldest, born in the United States, also died as a child. Perhaps because of her unspeakable suffering, Aida had an innate sense of injustice, which she passed on to me. My late wife Catherine was born in January 1940, just three weeks af- ter she was smuggled into the United States in her mother’s belly. Pregnant Jewish women were not allowed into the United States on visitors’ visas dur- ing World War II. The Nazis murdered Cathy’s maternal grandmother and that branch of Cathy’s family, except my mother-in-law. -

Radical Action and a National Antiwar Movement: the Vietnam Day Committee

Western Illinois Historical Review © 2012 Vol. IV, Spring 2012 ISSN 2153-1714 Radical Action and a National Antiwar Movement: The Vietnam Day Committee By Michael Lowe1 In August 1965, a few hundred demonstrators marched from the University of California, Berkeley campus to a provocative, dangerous antiwar demonstration. Flanked by policemen and flash bulbs, demonstrators stood on a Berkeley train track, carrying signs and chanting. A train carrying troops bound for the Oakland Army Terminal headed straight for them. Suspenseful seconds passed while many stayed put. The train let out an immense rush of steam, confusing demonstrators as a shrill, piercing conductor’s whistle rendered everything else chaotic but silent. One woman was pulled from the tracks moments before a collision, but other activists scrambling to escape the train’s path could not see through clouds of steam; the train to Oakland soon advanced forward, carrying troops closer to war. Throughout most of 1965 and the early months of 1966, Berkeley’s Vietnam Day Committee (VDC), an early antiwar organization which sought to build a nationwide consensus against the war, held rallies and supported the quick withdrawal of U.S. military forces in Vietnam. The group formed on the University of California, Berkeley campus while the Free Speech Movement (FSM) trials were reaching their conclusions; the VDC gained a great deal of attention among the general public and respect among the growing minority of antiwar students because of its connections with the FSM, which had recently achieved victories for student rights 1 Michael Lowe completed his research under the mentorship of Dr. -

Chapter 30.Pdf

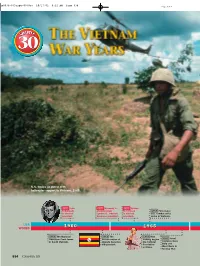

p0934-935aspe-0830co 10/17/02 9:22 AM Page 934 U.S. troops on patrol with helicopter support in Vietnam, 1965. 1960 John 1963 Kennedy is 1964 Lyndon F. Kennedy assassinated; B. Johnson 1965 First major is elected Lyndon B. Johnson is elected U.S. combat units president. becomes president. president. arrive in Vietnam. USA 1960 WORLD 1960 19651965 1960 The National 1962 The 1966 Mao Liberation Front forms African nation of Zedong begins 1967 Israel in South Vietnam. Uganda becomes the Cultural captures Gaza independent. Revolution Strip and in China. West Bank in Six-Day War. 934 CHAPTER 30 p0934-935aspe-0830co 10/17/02 9:22 AM Page 935 INTERACTINTERACT WITH HISTORY In 1965, America’s fight against com- munism has spread to Southeast Asia, where the United States is becoming increasingly involved in another country’s civil war. Unable to claim victory, U.S. generals call for an increase in the number of combat troops. Facing a shortage of volunteers, the president implements a draft. Who should be exempt from the draft? Examine the Issues • Should people who believe the war is wrong be forced to fight? • Should people with special skills be exempt? • How can a draft be made fair? RESEARCH LINKS CLASSZONE.COM Visit the Chapter 30 links for more information about The Vietnam War Years. 1968 Martin Luther King, Jr., and Robert Kennedy are 1970 Ohio 1973 United assassinated. National 1969 States signs Guard kills 1968 Richard U.S. troops 1972 cease-fire four students M. Nixon is begin their Richard M. with North 1974 Gerald R. -

14 Feb 2014 Final Update to the Kent State Truth Tribunal Submission To

14 Feb 2014 Final Update to the Kent State Truth Tribunal submission to the United Nations, Human Rights Committee The Kent State Truth Tribunal (KSTT) was founded in 2010 upon the emergence of new forensic evidence regarding the May 4, 1970 Kent State massacre. KSTT is a non- governmental organization focused on revealing truth and bringing justice to Kent State victims and survivors. Representing Allison Beth Krause, 19-year-old student protester slain at Kent State University on May 4, 1970: Doris L. Krause, mother and Laurel Krause, sister. The Kent State Truth Tribunal seeks an independent, impartial investigation into the May 4th Kent State massacre (Article 2 (Right to remedy); Article 6 (Right to life); Article 19 (Right to freedom of expression); Article 21 (Right to peaceful assembly)). In 2013 KSTT submitted information and a shadow report to the United Nations Human Rights Committee surrounding the May 4, 1970 Kent State shootings where Krause family member Allison was wrongfully killed. KSTT Submission: http://bit.ly/1f2X25i, KSTT Shadow Report: http://bit.ly/1kBSjfa US military bullets silenced Allison Krause’s protest against the United States war in Vietnam and President Nixon’s announced escalation of the war into Cambodia. On May 4, 1970, Allison stood and died for peace. From the revealing Kent State forensic evidence emerging in May 2010, we learned: "Participating American militia colluded at Kent State to organize and fight this battle against American student protesters, most of them too young to vote but old enough -

Shawyer Dissertation May 2008 Final Version

Copyright by Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer 2008 The Dissertation Committee for Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: Radical Street Theatre and the Yippie Legacy: A Performance History of the Youth International Party, 1967-1968 Committee: Jill Dolan, Supervisor Paul Bonin-Rodriguez Charlotte Canning Janet Davis Stacy Wolf Radical Street Theatre and the Yippie Legacy: A Performance History of the Youth International Party, 1967-1968 by Susanne Elizabeth Shawyer, B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May, 2008 Acknowledgements There are many people I want to thank for their assistance throughout the process of this dissertation project. First, I would like to acknowledge the generous support and helpful advice of my committee members. My supervisor, Dr. Jill Dolan, was present in every stage of the process with thought-provoking questions, incredible patience, and unfailing encouragement. During my years at the University of Texas at Austin Dr. Charlotte Canning has continually provided exceptional mentorship and modeled a high standard of scholarly rigor and pedagogical generosity. Dr. Janet Davis and Dr. Stacy Wolf guided me through my earliest explorations of the Yippies and pushed me to consider the complex historical and theoretical intersections of my performance scholarship. I am grateful for the warm collegiality and insightful questions of Dr. Paul Bonin-Rodriguez. My committee’s wise guidance has pushed me to be a better scholar. -

Middle Grades Social Studies

OHIO ASSESSMENTS FOR EDUCATORS (OAE) FIELD 031: MIDDLE GRADES SOCIAL STUDIES ASSESSMENT FRAMEWORK November 2017 Approximate Range of Content Domain Percentage of Competencies Assessment Score I. History 0001–0008 40% II. Geography and Culture 0009–0011 21% III. Government 0012–0014 19% IV. Economics 0015–0016 10% V. Ohio in the United States 0017 10% Copyright © 2017 Pearson Education, Inc. or its affiliate(s). All rights reserved. Evaluation Systems, Pearson, P.O. Box 226, Amherst, MA 01004 Pearson and its logo are trademarks, in the U.S. and/or other countries, of Pearson Education, Inc. or its affiliate(s). This document may not be reproduced for commercial use but may be copied for educational purposes. Middle Grades Social Studies: Approximate percentage of assessment score by competency Approximate Content Domain Percentage of Assessment Score I. History Competency 0001 6% Competency 0002 7% Competency 0003 7% Competency 0004 2% Competency 0005 7% Competency 0006 7% Competency 0007 2% Competency 0008 2% Domain I: Total Approximate Percentage of Assessment Score 40% II. Geography and Culture Competency 0009 7% Competency 0010 7% Competency 0011 7% Domain II: Total Approximate Percentage of Assessment Score 21% III. Government Competency 0012 6% Competency 0013 7% Competency 0014 6% Domain III: Total Approximate Percentage of Assessment Score 19% IV. Economics Competency 0015 8% Competency 0016 2% Domain IV: Total Approximate Percentage of Assessment Score 10% V. Ohio in the United States Competency 0017 10% Domain V: Total Approximate Percentage of Assessment Score 10% Copyright © 2017 Pearson Education, Inc. or its affiliate(s). All rights reserved. Evaluation Systems, Pearson, P.O. -

March to June 2014 Calendar

April to June 2014 DIVISION OF PUBLIC PROGRAMS EVENTS, EXHIBITIONS, AND PROGRAMS EXHIBITION OPENINGS APRIL April 2 to May 16 Freedom Summer volunteers registering GAIL BORDEN PUBLIC LIBRARY, locals. From the documentary “American Experience: Freedom Summer” airing Elgin, IL June 24 on PBS Lincoln: The Constitution and (check local listings). the Civil War Courtesy, Johnson Publishing Company, LLC. All rights reserved. Traveling. Organized by the National www.pbs.org/wgbh/ Constitution Center. www.ala.org americanexperience/films/ freedomsummer April 2 to May 16 LILLIE M. EVANS LIBRARY DISTRICT, Princeville, IL Lincoln: The Constitution and the Civil War Traveling. Organized by the National April 2 to May 16 April 5 Constitution Center. www.ala.org OKLAHOMA HISTORICAL SOCIETY NATIONAL CIVIL RIGHTS MUSEUM, April 2 to May 16 AND OKLAHOMA CIVIL WAR Memphis, TN LINFIELD COLLEGE, JERELD R. SESQUICENTENNIAL COMMISSION, Lorraine Motel Exhibits NICHOLSON LIBRARY, Enid, OK Long-term. www.civilrightsmuseum.org McMinnville, OR Lincoln: The Constitution and April 26 to August 17 Lincoln: The Constitution and the Civil War MISSOURI HISTORY MUSEUM, the Civil War Traveling. St. Louis, MO Traveling. April 2 to May 16 American Spirits: The Rise and April 2 to May 16 SOUTH CAROLINA STATE MUSEUM, Fall of Prohibition MISSISSIPPI STATE UNIVERSITY, Columbia, SC Traveling. Organized by the National Mississippi State, MS Constitution Center. constitutioncenter.org Lincoln: The Constitution and Lincoln: The Constitution and the Civil War April 28 to May 19 the Civil War Traveling. SCOTCH PLAINS PUBLIC LIBRARY, Traveling. Scotch Plains, NJ April 2 to June 13 April 2 to May 16 SPRING LAKE DISTRICT LIBRARY, Civil War 150: Exploring the War OHIO UNIVERSITY, Spring Lake, MI and its Meaning Through the St. -

Commemorating the Kent State Tragedy Through Victims' Trauma In

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Papers in Communication Studies Communication Studies, Department of 2009 Commemorating the Kent State Tragedy through Victims’ Trauma in Television News Coverage, 1990–2000 Kristen Hoerl Auburn University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstudiespapers Part of the Critical and Cultural Studies Commons, Gender, Race, Sexuality, and Ethnicity in Communication Commons, and the Other Communication Commons Hoerl, Kristen, "Commemorating the Kent State Tragedy through Victims’ Trauma in Television News Coverage, 1990–2000" (2009). Papers in Communication Studies. 191. http://digitalcommons.unl.edu/commstudiespapers/191 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Communication Studies, Department of at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Papers in Communication Studies by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Published in The Communication Review 12:2 (2009), pp. 107–131; doi: 10.1080/10714420902921101 Copyright © 2009 Taylor & Francis Group, LLC. Used by permission. Published online May 27, 2009. Commemorating the Kent State Tragedy through Victims’ Trauma in Television News Coverage, 1990–2000 Kristen Hoerl Department of Communication and Journalism, Auburn University, Auburn, Alabama, USA Corresponding author – Kristen Hoerl, Department of Communication and Journalism, Auburn University, 0336 Haley, Auburn, AL 36849, USA, email [email protected] Abstract On May 4, 1970, the Ohio National Guard fired into a crowd at Kent State University and killed four students. This essay critically interprets mainstream television journalism that commemorated the shootings in the past 18 years. Throughout this coverage, predominant framing devices depoliticized the Kent State tragedy by characterizing both former students and guard members as trauma victims.