America's Role in the Arctic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

New Siberian Islands Archipelago)

Detrital zircon ages and provenance of the Upper Paleozoic successions of Kotel’ny Island (New Siberian Islands archipelago) Victoria B. Ershova1,*, Andrei V. Prokopiev2, Andrei K. Khudoley1, Nikolay N. Sobolev3, and Eugeny O. Petrov3 1INSTITUTE OF EARTH SCIENCE, ST. PETERSBURG STATE UNIVERSITY, UNIVERSITETSKAYA NAB. 7/9, ST. PETERSBURG 199034, RUSSIA 2DIAMOND AND PRECIOUS METAL GEOLOGY INSTITUTE, SIBERIAN BRANCH, RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, LENIN PROSPECT 39, YAKUTSK 677980, RUSSIA 3RUSSIAN GEOLOGICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE (VSEGEI), SREDNIY PROSPECT 74, ST. PETERSBURG 199106, RUSSIA ABSTRACT Plate-tectonic models for the Paleozoic evolution of the Arctic are numerous and diverse. Our detrital zircon provenance study of Upper Paleozoic sandstones from Kotel’ny Island (New Siberian Island archipelago) provides new data on the provenance of clastic sediments and crustal affinity of the New Siberian Islands. Upper Devonian–Lower Carboniferous deposits yield detrital zircon populations that are consistent with the age of magmatic and metamorphic rocks within the Grenvillian-Sveconorwegian, Timanian, and Caledonian orogenic belts, but not with the Siberian craton. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test reveals a strong similarity between detrital zircon populations within Devonian–Permian clastics of the New Siberian Islands, Wrangel Island (and possibly Chukotka), and the Severnaya Zemlya Archipelago. These results suggest that the New Siberian Islands, along with Wrangel Island and the Severnaya Zemlya Archipelago, were located along the northern margin of Laurentia-Baltica in the Late Devonian–Mississippian and possibly made up a single tectonic block. Detrital zircon populations from the Permian clastics record a dramatic shift to a Uralian provenance. The data and results presented here provide vital information to aid Paleozoic tectonic reconstructions of the Arctic region prior to opening of the Mesozoic oceanic basins. -

Geography Notes.Pdf

THE GLOBE What is a globe? a small model of the Earth Parts of a globe: equator - the line on the globe halfway between the North Pole and the South Pole poles - the northern-most and southern-most points on the Earth 1. North Pole 2. South Pole hemispheres - half of the earth, divided by the equator (North & South) and the prime meridian (East and West) 1. Northern Hemisphere 2. Southern Hemisphere 3. Eastern Hemisphere 4. Western Hemisphere continents - the largest land areas on Earth 1. North America 2. South America 3. Europe 4. Asia 5. Africa 6. Australia 7. Antarctica oceans - the largest water areas on Earth 1. Atlantic Ocean 2. Pacific Ocean 3. Indian Ocean 4. Arctic Ocean 5. Antarctic Ocean WORLD MAP ** NOTE: Our textbooks call the “Southern Ocean” the “Antarctic Ocean” ** North America The three major countries of North America are: 1. Canada 2. United States 3. Mexico Where Do We Live? We live in the Western & Northern Hemispheres. We live on the continent of North America. The other 2 large countries on this continent are Canada and Mexico. The name of our country is the United States. There are 50 states in it, but when it first became a country, there were only 13 states. The name of our state is New York. Its capital city is Albany. GEOGRAPHY STUDY GUIDE You will need to know: VOCABULARY: equator globe hemisphere continent ocean compass WORLD MAP - be able to label 7 continents and 5 oceans 3 Large Countries of North America 1. United States 2. Canada 3. -

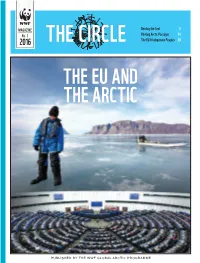

The Eu and the Arctic

MAGAZINE Dealing the Seal 8 No. 1 Piloting Arctic Passages 14 2016 THE CIRCLE The EU & Indigenous Peoples 20 THE EU AND THE ARCTIC PUBLISHED BY THE WWF GLOBAL ARCTIC PROGRAMME TheCircle0116.indd 1 25.02.2016 10.53 THE CIRCLE 1.2016 THE EU AND THE ARCTIC Contents EDITORIAL Leaving a legacy 3 IN BRIEF 4 ALYSON BAILES What does the EU want, what can it offer? 6 DIANA WALLIS Dealing the seal 8 ROBIN TEVERSON ‘High time’ EU gets observer status: UK 10 ADAM STEPIEN A call for a two-tier EU policy 12 MARIA DELIGIANNI Piloting the Arctic Passages 14 TIMO KOIVUROVA Finland: wearing two hats 16 Greenland – walking the middle path 18 FERNANDO GARCES DE LOS FAYOS The European Parliament & EU Arctic policy 19 CHRISTINA HENRIKSEN The EU and Arctic Indigenous peoples 20 NICOLE BIEBOW A driving force: The EU & polar research 22 THE PICTURE 24 The Circle is published quar- Publisher: Editor in Chief: Clive Tesar, COVER: terly by the WWF Global Arctic WWF Global Arctic Programme [email protected] (Top:) Local on sea ice in Uumman- Programme. Reproduction and 8th floor, 275 Slater St., Ottawa, naq, Greenland. quotation with appropriate credit ON, Canada K1P 5H9. Managing Editor: Becky Rynor, Photo: Lawrence Hislop, www.grida.no are encouraged. Articles by non- Tel: +1 613-232-8706 [email protected] (Bottom:) European Parliament, affiliated sources do not neces- Fax: +1 613-232-4181 Strasbourg, France. sarily reflect the views or policies Design and production: Photo: Diliff, Wikimedia Commonss of WWF. Send change of address Internet: www.panda.org/arctic Film & Form/Ketill Berger, and subscription queries to the [email protected] ABOVE: Sarek glacier, Sarek National address on the right. -

A Newly Discovered Glacial Trough on the East Siberian Continental Margin

Clim. Past Discuss., doi:10.5194/cp-2017-56, 2017 Manuscript under review for journal Clim. Past Discussion started: 20 April 2017 c Author(s) 2017. CC-BY 3.0 License. De Long Trough: A newly discovered glacial trough on the East Siberian Continental Margin Matt O’Regan1,2, Jan Backman1,2, Natalia Barrientos1,2, Thomas M. Cronin3, Laura Gemery3, Nina 2,4 5 2,6 7 1,2,8 9,10 5 Kirchner , Larry A. Mayer , Johan Nilsson , Riko Noormets , Christof Pearce , Igor Semilietov , Christian Stranne1,2,5, Martin Jakobsson1,2. 1 Department of Geological Sciences, Stockholm University, Stockholm, 106 91, Sweden 2 Bolin Centre for Climate Research, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden 10 3 US Geological Survey MS926A, Reston, Virginia, 20192, USA 4 Department of Physical Geography (NG), Stockholm University, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 5 Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, University of New Hampshire, New Hampshire 03824, USA 6 Department of Meteorology, Stockholm University, Stockholm, 106 91, Sweden 7 University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS), P O Box 156, N-9171 Longyearbyen, Svalbard 15 8 Department of Geoscience, Aarhus University, Aarhus, 8000, Denmark 9 Pacific Oceanological Institute, Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 690041 Vladivostok, Russia 10 Tomsk National Research Polytechnic University, Tomsk, Russia Correspondence to: Matt O’Regan ([email protected]) 20 Abstract. Ice sheets extending over parts of the East Siberian continental shelf have been proposed during the last glacial period, and during the larger Pleistocene glaciations. The sparse data available over this sector of the Arctic Ocean has left the timing, extent and even existence of these ice sheets largely unresolved. -

Natural Variability of the Arctic Ocean Sea Ice During the Present Interglacial

Natural variability of the Arctic Ocean sea ice during the present interglacial Anne de Vernala,1, Claude Hillaire-Marcela, Cynthia Le Duca, Philippe Robergea, Camille Bricea, Jens Matthiessenb, Robert F. Spielhagenc, and Ruediger Steinb,d aGeotop-Université du Québec à Montréal, Montréal, QC H3C 3P8, Canada; bGeosciences/Marine Geology, Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, 27568 Bremerhaven, Germany; cOcean Circulation and Climate Dynamics Division, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research, 24148 Kiel, Germany; and dMARUM Center for Marine Environmental Sciences and Faculty of Geosciences, University of Bremen, 28334 Bremen, Germany Edited by Thomas M. Cronin, U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, VA, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Jean Jouzel August 26, 2020 (received for review May 6, 2020) The impact of the ongoing anthropogenic warming on the Arctic such an extrapolation. Moreover, the past 1,400 y only encom- Ocean sea ice is ascertained and closely monitored. However, its pass a small fraction of the climate variations that occurred long-term fate remains an open question as its natural variability during the Cenozoic (7, 8), even during the present interglacial, on centennial to millennial timescales is not well documented. i.e., the Holocene (9), which began ∼11,700 y ago. To assess Here, we use marine sedimentary records to reconstruct Arctic Arctic sea-ice instabilities further back in time, the analyses of sea-ice fluctuations. Cores collected along the Lomonosov Ridge sedimentary archives is required but represents a challenge (10, that extends across the Arctic Ocean from northern Greenland to 11). Suitable sedimentary sequences with a reliable chronology the Laptev Sea were radiocarbon dated and analyzed for their and biogenic content allowing oceanographical reconstructions micropaleontological and palynological contents, both bearing in- can be recovered from Arctic Ocean shelves, but they rarely formation on the past sea-ice cover. -

Chapter 7 Arctic Oceanography; the Path of North Atlantic Deep Water

Chapter 7 Arctic oceanography; the path of North Atlantic Deep Water The importance of the Southern Ocean for the formation of the water masses of the world ocean poses the question whether similar conditions are found in the Arctic. We therefore postpone the discussion of the temperate and tropical oceans again and have a look at the oceanography of the Arctic Seas. It does not take much to realize that the impact of the Arctic region on the circulation and water masses of the World Ocean differs substantially from that of the Southern Ocean. The major reason is found in the topography. The Arctic Seas belong to a class of ocean basins known as mediterranean seas (Dietrich et al., 1980). A mediterranean sea is defined as a part of the world ocean which has only limited communication with the major ocean basins (these being the Pacific, Atlantic, and Indian Oceans) and where the circulation is dominated by thermohaline forcing. What this means is that, in contrast to the dynamics of the major ocean basins where most currents are driven by the wind and modified by thermohaline effects, currents in mediterranean seas are driven by temperature and salinity differences (the salinity effect usually dominates) and modified by wind action. The reason for the dominance of thermohaline forcing is the topography: Mediterranean Seas are separated from the major ocean basins by sills, which limit the exchange of deeper waters. Fig. 7.1. Schematic illustration of the circulation in mediterranean seas; (a) with negative precipitation - evaporation balance, (b) with positive precipitation - evaporation balance. -

The EU Arctic Cluster Implementing the European Arctic Policy and Fostering International Cooperation

The EU Arctic Cluster Implementing the European Arctic Policy and fostering international cooperation www.eu-arcticcluster.eu Photo: Steffen Olsen Integrated European Union Policy for the Arctic 3 priority areas 1. Climate change and safeguarding the Arctic Environment 2. Sustainable Development in and around the Arctic 3. International Cooperation on Arctic Issues. Why is the EU funding Arctic research? • Global consequences and risks of Arctic change. • Mitigation and adaptation strategies in the Arctic are part of the EU's efforts to combat climate change and to implement the Paris Agreement. • Contribution to the achievement of the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). “Spending in Arctic research • Development of appropriate policies, including those and relating to climate change and sustainable development. observations is not a cost but an investment that generates benefits.” Andrea Tilche, European Commission Photo: SPRS Photo: Witold Kaszkin Photo: IPEV The EU Arctic Cluster EU-PolarNet Connecting Science with Society Is the world’s largest consortium of expertise and infrastructure for polar research with the ambition to co-design a strategic framework to prioritise science, advice the European Commission on polar issues, optimise the use of polar infrastructure, and broker international partnerships. 17 European countries 22 consortium members 25 cooperation partners Coordinator: AWI, Germany Duration: 03.2015 – 02.2020 Budget: 2.2 Mio Euro www.eu-polarnet.eu Photo: AWI INTAROS Integrated Arctic Observation System Climate gas fluxes in Alaska and Siberia Will develop an integrated Arctic Oceanography Sea ice data from buoys Observation System by extending, and acoustics in in the Central Arctic improving and unifying existing the Beaufort Sea Soil carbon and systems in the different regions of the snow data from tundra in Canada Arctic. -

Arctic Report Card 2018 Effects of Persistent Arctic Warming Continue to Mount

Arctic Report Card 2018 Effects of persistent Arctic warming continue to mount 2018 Headlines 2018 Headlines Video Executive Summary Effects of persistent Arctic warming continue Contacts to mount Vital Signs Surface Air Temperature Continued warming of the Arctic atmosphere Terrestrial Snow Cover and ocean are driving broad change in the Greenland Ice Sheet environmental system in predicted and, also, Sea Ice unexpected ways. New emerging threats Sea Surface Temperature are taking form and highlighting the level of Arctic Ocean Primary uncertainty in the breadth of environmental Productivity change that is to come. Tundra Greenness Other Indicators River Discharge Highlights Lake Ice • Surface air temperatures in the Arctic continued to warm at twice the rate relative to the rest of the globe. Arc- Migratory Tundra Caribou tic air temperatures for the past five years (2014-18) have exceeded all previous records since 1900. and Wild Reindeer • In the terrestrial system, atmospheric warming continued to drive broad, long-term trends in declining Frostbites terrestrial snow cover, melting of theGreenland Ice Sheet and lake ice, increasing summertime Arcticriver discharge, and the expansion and greening of Arctic tundravegetation . Clarity and Clouds • Despite increase of vegetation available for grazing, herd populations of caribou and wild reindeer across the Harmful Algal Blooms in the Arctic tundra have declined by nearly 50% over the last two decades. Arctic • In 2018 Arcticsea ice remained younger, thinner, and covered less area than in the past. The 12 lowest extents in Microplastics in the Marine the satellite record have occurred in the last 12 years. Realms of the Arctic • Pan-Arctic observations suggest a long-term decline in coastal landfast sea ice since measurements began in the Landfast Sea Ice in a 1970s, affecting this important platform for hunting, traveling, and coastal protection for local communities. -

The Arctic Migratory Bird Initiative (AMBI) Work Plan 2015 - 2019

ACSAO-CA04 Whitehorse / Mar 2015 CAFF: AMBI Work Plan 2015-2019 The Arctic Migratory Bird Initiative (AMBI) Work Plan 2015 - 2019 Table of Contents Introduction and Context ................................................................................................................. 4 Links to other initiatives ............................................................................................................................ 5 Convention on Biological Diversity ................................................................................................................... 6 Convention on Migratory Species ..................................................................................................................... 7 Ramsar .............................................................................................................................................................. 8 World Heritage Convention .............................................................................................................................. 9 The AMBI Flyway workplans .................................................................................................................... 10 Implementation, monitoring and evaluation ............................................................................................ 10 Annex 1. Priority species for AMBI conservation efforts ......................................................................... 12 ARCTIC MIGRATORY BIRDS INITIATIVE (AMBI): WORKPLAN FOR THE ‘EAST ASIAN-AUSTRALASIAN -

Us Military Options to Enhance Arctic Defense Timothy Greenhaw, Daniel L

US MILITARY OPTIONS TO ENHANCE ARCTIC DEFENSE TIMOTHY GREENHAW, DANIEL L. MAGRUDER JR., RODRICK H. MCHATY, AND MICHAEL SINCLAIR MAY 2021 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Despite all the focus on strategic competition in Europe and Asia, one region of the world has at long last begun receiving the attention it warrants from the U.S. military: the Arctic. The Arctic is of unique importance to all Americans. First, the United States is one of just eight sovereign Arctic states — joined by Canada, Denmark (thanks to its autonomous territory Greenland), Finland, Iceland, Norway, Russia, and Sweden — which allows for the exercise of certain sovereign rights in the region and bestows member status in the international Arctic Council.1 China is, of course, notably absent, despite its self-proclaimed (and at best dubious) status as a “near-Arctic” state2 and its observer status on the Arctic Council. Second, the effects of global climate change are increasing access to previously inaccessible Arctic areas and important transit and trade routes. This increased access results in yet another theatre for strategic competition, and thus, it is curious that the Arctic was not mentioned in the Biden administration’s Interim National Security Guidance3 — although it has engaged on Arctic issues around this month’s Arctic Council summit.4 To better elevate Arctic issues to their proper place in strategic dialogue, especially amongst the armed forces, we argue that the U.S. military should prioritize engagement through international, defense-oriented bodies like the Arctic Security Forces Roundtable, redraw geographic combatant command borders to include the Arctic region under NORTHCOM, and continue improving operational relationships with allied and partner nations through joint exercises and training. -

The Aral Sea Cannot Be Saved, but It Is Possible to Develop a New Tourist Region

European Journal of Research Development and Sustainability (EJRDS) Available Online at: https://www.scholarzest.com Vol. 2 No. 3, March 2021, ISSN: 2660-5570 THE ARAL SEA CANNOT BE SAVED, BUT IT IS POSSIBLE TO DEVELOP A NEW TOURIST REGION Candidate of Economic Sciences, Associate Professor Dilfuza Igamberdievna Abidova, Senior lecturer TSUE, Uzbekistan, assistant Bakhromov Akmal Abduvahid oʻgʻli TSUE Doctoral student Dekhkonov Burkhon Rustamovich TSUE Article history: Abstract: Received: 28th February 2021 There are many different views on the causes of the disappearance of the Aral Accepted: 7th March 2021 sea. The Aral sea, the former is unique, beautiful and one of the largest Published: 30th March 2021 enclosed water in the world, almost during the lifetime of one generation found itself on the verge of extinction, which resulted in an unprecedented disaster and irreparable damage to the livelihoods of the populations, ecosystems and biodiversity of the Aral sea region. Despite the current environmental catastrophe, the Aral Sea tragedy provides the opportunity for a new tourist region Keywords: Central Asian, Aral sea, climatic condition, ecological situation, new tourist region. disaster, ecology, water resources, ecosystem, biodiversity, infrastructure improvement, anthropogenic interference, hydrological regime of rivers, inland water body, climate of the Aral sea region, cyclical nature INTRODUCTION. The Aral sea is one of the largest closed inland brackish water bodies of the globe. Located in the heart of Central Asian deserts at an altitude of 53 m above sea level, the Aral sea acted giant vaporizer. From evaporated and entered the atmosphere about 60 cubic km of water. Before 1960, the Aral sea was the fourth largest lake in the world.