Why the Arctic Matters America’S Responsibilities As an Arctic Nation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

North America Other Continents

Arctic Ocean Europe North Asia America Atlantic Ocean Pacific Ocean Africa Pacific Ocean South Indian America Ocean Oceania Southern Ocean Antarctica LAND & WATER • The surface of the Earth is covered by approximately 71% water and 29% land. • It contains 7 continents and 5 oceans. Land Water EARTH’S HEMISPHERES • The planet Earth can be divided into four different sections or hemispheres. The Equator is an imaginary horizontal line (latitude) that divides the earth into the Northern and Southern hemispheres, while the Prime Meridian is the imaginary vertical line (longitude) that divides the earth into the Eastern and Western hemispheres. • North America, Earth’s 3rd largest continent, includes 23 countries. It contains Bermuda, Canada, Mexico, the United States of America, all Caribbean and Central America countries, as well as Greenland, which is the world’s largest island. North West East LOCATION South • The continent of North America is located in both the Northern and Western hemispheres. It is surrounded by the Arctic Ocean in the north, by the Atlantic Ocean in the east, and by the Pacific Ocean in the west. • It measures 24,256,000 sq. km and takes up a little more than 16% of the land on Earth. North America 16% Other Continents 84% • North America has an approximate population of almost 529 million people, which is about 8% of the World’s total population. 92% 8% North America Other Continents • The Atlantic Ocean is the second largest of Earth’s Oceans. It covers about 15% of the Earth’s total surface area and approximately 21% of its water surface area. -

Papers Published And/Or Accepted for Publication in 2018-2019 (List Incomplete)

Papers published and/or accepted for publication in 2018-2019 (list incomplete) Allington, G. R. H., Fernandez-Gimenez M. E., Chen Belt (ADB). In: (G Gutman, J Chen, GM Henebry, J, and Brown and D G 2018: Combining M Kappas, eds.) Landscape Dynamics across participatory scenario planning and systems Drylands of Greater Central Asia: People, modeling to identify drivers of future sustainability Societies and Ecosystems. Springer. Chapter 10. on the Mongolian Plateau. Ecology and Chen Y, Tao Y, Cheng Y, Ju W, Ye J, Hickler T, Liao Society 23(2):9. C, Feng L and Ruan H 2018: Great uncertainties https://doi.org/10.5751/ES-10034-230209 in modeling grazing impact on carbon An S, Chen X, Zhang XY, Yan D and Henebry GM sequestration: a multi-model inter-comparison in 2018. An exploration of terrain effects on land temperate Eurasian Steppe Environ. Res. surface phenology across the Qinghai-Tibetan Lett. 13 075005 Plateau using Landsat ETM+ and OLI Chen Y, Fei X, Groisman P, Sun Z, Zhang J, and Qin data Remote Sensing 10(7):1069. Z, 2019: Contrasting policy shifts influence the https://doi.org/10.3390/rs10071069 pattern of vegetation production and C Bastos A , Peregon A, Gani ÉA, Khudyaev S, Yue C, sequestration over pasture systems: a regional- Li W, Gouveia CM and Ciais P 2018 Influence of scale comparison in Temperate Eurasian Steppe. high-latitude warming and land-use changes in the Agricultural Systems, Accepted. early 20th century northern Eurasian CO2 sink Deppermann A, Balkovič J, Bundle S-C, di Fulvio F, Environ. Res. -

Recent North Magnetic Pole Acceleration Towards Siberia Caused by flux Lobe Elongation

Recent north magnetic pole acceleration towards Siberia caused by flux lobe elongation Philip W. Livermore,1∗, Christopher C. Finlay 2, Matthew Bayliff 1 1School of Earth and Environment, University of Leeds, Leeds, LS2 9JT, UK, 2DTU Space, Technical University of Denmark, 2800 Kgs. Lyngby, Copenhagen, Denmark ∗To whom correspondence should be addressed; E-mail: [email protected]. Abstract The wandering of Earth’s north magnetic pole, the location where the magnetic field points vertically downwards, has long been a topic of scien- tific fascination. Since the first in-situ measurements in 1831 of its location in the Canadian arctic, the pole has drifted inexorably towards Siberia, ac- celerating between 1990 and 2005 from its historic speed of 0-15 km/yr to its present speed of 50-60 km/yr. In late October 2017 the north magnetic pole crossed the international date line, passing within 390 km of the geo- graphic pole, and is now moving southwards. Here we show that over the last two decades the position of the north magnetic pole has been largely determined by two large-scale lobes of negative magnetic flux on the core- mantle-boundary under Canada and Siberia. Localised modelling shows that elongation of the Canadian lobe, likely caused by an alteration in the pattern of core-flow between 1970 and 1999, significantly weakened its signature on Earth’s surface causing the pole to accelerate towards Siberia. A range of simple models that capture this process indicate that over the next decade arXiv:2010.11033v1 [physics.geo-ph] 21 Oct 2020 the north magnetic pole will continue on its current trajectory travelling a further 390-660 km towards Siberia. -

New Siberian Islands Archipelago)

Detrital zircon ages and provenance of the Upper Paleozoic successions of Kotel’ny Island (New Siberian Islands archipelago) Victoria B. Ershova1,*, Andrei V. Prokopiev2, Andrei K. Khudoley1, Nikolay N. Sobolev3, and Eugeny O. Petrov3 1INSTITUTE OF EARTH SCIENCE, ST. PETERSBURG STATE UNIVERSITY, UNIVERSITETSKAYA NAB. 7/9, ST. PETERSBURG 199034, RUSSIA 2DIAMOND AND PRECIOUS METAL GEOLOGY INSTITUTE, SIBERIAN BRANCH, RUSSIAN ACADEMY OF SCIENCES, LENIN PROSPECT 39, YAKUTSK 677980, RUSSIA 3RUSSIAN GEOLOGICAL RESEARCH INSTITUTE (VSEGEI), SREDNIY PROSPECT 74, ST. PETERSBURG 199106, RUSSIA ABSTRACT Plate-tectonic models for the Paleozoic evolution of the Arctic are numerous and diverse. Our detrital zircon provenance study of Upper Paleozoic sandstones from Kotel’ny Island (New Siberian Island archipelago) provides new data on the provenance of clastic sediments and crustal affinity of the New Siberian Islands. Upper Devonian–Lower Carboniferous deposits yield detrital zircon populations that are consistent with the age of magmatic and metamorphic rocks within the Grenvillian-Sveconorwegian, Timanian, and Caledonian orogenic belts, but not with the Siberian craton. The Kolmogorov-Smirnov test reveals a strong similarity between detrital zircon populations within Devonian–Permian clastics of the New Siberian Islands, Wrangel Island (and possibly Chukotka), and the Severnaya Zemlya Archipelago. These results suggest that the New Siberian Islands, along with Wrangel Island and the Severnaya Zemlya Archipelago, were located along the northern margin of Laurentia-Baltica in the Late Devonian–Mississippian and possibly made up a single tectonic block. Detrital zircon populations from the Permian clastics record a dramatic shift to a Uralian provenance. The data and results presented here provide vital information to aid Paleozoic tectonic reconstructions of the Arctic region prior to opening of the Mesozoic oceanic basins. -

Geography Notes.Pdf

THE GLOBE What is a globe? a small model of the Earth Parts of a globe: equator - the line on the globe halfway between the North Pole and the South Pole poles - the northern-most and southern-most points on the Earth 1. North Pole 2. South Pole hemispheres - half of the earth, divided by the equator (North & South) and the prime meridian (East and West) 1. Northern Hemisphere 2. Southern Hemisphere 3. Eastern Hemisphere 4. Western Hemisphere continents - the largest land areas on Earth 1. North America 2. South America 3. Europe 4. Asia 5. Africa 6. Australia 7. Antarctica oceans - the largest water areas on Earth 1. Atlantic Ocean 2. Pacific Ocean 3. Indian Ocean 4. Arctic Ocean 5. Antarctic Ocean WORLD MAP ** NOTE: Our textbooks call the “Southern Ocean” the “Antarctic Ocean” ** North America The three major countries of North America are: 1. Canada 2. United States 3. Mexico Where Do We Live? We live in the Western & Northern Hemispheres. We live on the continent of North America. The other 2 large countries on this continent are Canada and Mexico. The name of our country is the United States. There are 50 states in it, but when it first became a country, there were only 13 states. The name of our state is New York. Its capital city is Albany. GEOGRAPHY STUDY GUIDE You will need to know: VOCABULARY: equator globe hemisphere continent ocean compass WORLD MAP - be able to label 7 continents and 5 oceans 3 Large Countries of North America 1. United States 2. Canada 3. -

Map and Compass

UE CG 039-089 2018_UE CG 039-089 2018 2018-08-29 9:57 AM Page 56 MAP The north magnetic pole is not the same as the geographic North Pole, also known as AND COMPASS true north, which is the northern end of the axis around which the earth spins. In fact, the north magnetic pole currently lies Background Information approximately 800 mi (1300 km) south of the geographic North Pole, in northern A compass is an instrument that people use Canada. And because the north magnetic to find a direction in relation to the earth as pole migrates at 6.6 mi (10 km) per year, its a whole. The magnetic needle in the location is constantly changing. compass, which is the freely moving needle in the compass that has a red end, points The meridians of longitude on maps and north. More specifically, this needle points globes are based upon the geographic to the north magnetic pole, the northern North Pole rather than the north magnetic end of the earth’s magnetic field, which pole. This means that magnetic north, the can be imagined as lines of magnetism that direction that a compass indicates as north, leave the south magnetic pole, flow north is not the same direction as maps indicate around the earth, and then enter the north for north. Magnetic declination, the magnetic pole. difference in the angle between magnetic north and true north must, therefore, be Any magnetized object, an object with two taken into account when navigating with a oppositely charged ends, such as a magnet map and a compass. -

MARCH 10, 2011 Iditarod 39 on the Trail to Nome

Photo by Nikolai Ivanoff WHY DID THE MOOSE CROSS THE ROAD?— Because they want to cross the Glacier Creek Road and see what was going on at the Rock Creek Mine. C VOLUME CXI NO. 10 MARCH 10, 2011 Iditarod 39 on the trail to Nome By Diana Haecker dubbed the Last Great Race. Seen at The 2011 Iditarod Trail Sled Dog the Avenue to wish mushers good race is underway with 62 mushers luck were Alaska senators Lisa and their dogs heading for Nome. Murkowski and Mark Begich, Gov- The first days of the race saw sunny ernor Sean Parnell, Lt. Governor weather, not a cloud in the sky and Mead Treadwell and Anchorage fast trails leading into the Alaska Mayor Dan Sullivan. Also on hand Range. But it will take a crystal ball to send off the teams was Nome to predict how the rest of the race is Mayor Denise Michaels and Iditarod going to shape up. Weather condi- Trail Committee Director John Han- tions, may they be “hot” or brutally deland. cold, stormy or calm, are dictating Under blue skies, with helicopters trail conditions and that in turn in- buzzing aloft and thousands of fans fluences a great deal how the dogs lining the city streets and trails lead- and their mushers are coping with ing out to Campbell airstrip, the whatever Mother Nature throws at mushers were cheered by fans from them. near and far. The ceremonial start in Anchorage Florence Busch was wearing bib took place on Saturday, March 5 Number One as the honorary with droves of people lining Fourth musher. -

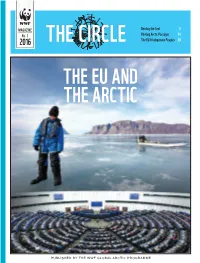

The Eu and the Arctic

MAGAZINE Dealing the Seal 8 No. 1 Piloting Arctic Passages 14 2016 THE CIRCLE The EU & Indigenous Peoples 20 THE EU AND THE ARCTIC PUBLISHED BY THE WWF GLOBAL ARCTIC PROGRAMME TheCircle0116.indd 1 25.02.2016 10.53 THE CIRCLE 1.2016 THE EU AND THE ARCTIC Contents EDITORIAL Leaving a legacy 3 IN BRIEF 4 ALYSON BAILES What does the EU want, what can it offer? 6 DIANA WALLIS Dealing the seal 8 ROBIN TEVERSON ‘High time’ EU gets observer status: UK 10 ADAM STEPIEN A call for a two-tier EU policy 12 MARIA DELIGIANNI Piloting the Arctic Passages 14 TIMO KOIVUROVA Finland: wearing two hats 16 Greenland – walking the middle path 18 FERNANDO GARCES DE LOS FAYOS The European Parliament & EU Arctic policy 19 CHRISTINA HENRIKSEN The EU and Arctic Indigenous peoples 20 NICOLE BIEBOW A driving force: The EU & polar research 22 THE PICTURE 24 The Circle is published quar- Publisher: Editor in Chief: Clive Tesar, COVER: terly by the WWF Global Arctic WWF Global Arctic Programme [email protected] (Top:) Local on sea ice in Uumman- Programme. Reproduction and 8th floor, 275 Slater St., Ottawa, naq, Greenland. quotation with appropriate credit ON, Canada K1P 5H9. Managing Editor: Becky Rynor, Photo: Lawrence Hislop, www.grida.no are encouraged. Articles by non- Tel: +1 613-232-8706 [email protected] (Bottom:) European Parliament, affiliated sources do not neces- Fax: +1 613-232-4181 Strasbourg, France. sarily reflect the views or policies Design and production: Photo: Diliff, Wikimedia Commonss of WWF. Send change of address Internet: www.panda.org/arctic Film & Form/Ketill Berger, and subscription queries to the [email protected] ABOVE: Sarek glacier, Sarek National address on the right. -

A Newly Discovered Glacial Trough on the East Siberian Continental Margin

Clim. Past Discuss., doi:10.5194/cp-2017-56, 2017 Manuscript under review for journal Clim. Past Discussion started: 20 April 2017 c Author(s) 2017. CC-BY 3.0 License. De Long Trough: A newly discovered glacial trough on the East Siberian Continental Margin Matt O’Regan1,2, Jan Backman1,2, Natalia Barrientos1,2, Thomas M. Cronin3, Laura Gemery3, Nina 2,4 5 2,6 7 1,2,8 9,10 5 Kirchner , Larry A. Mayer , Johan Nilsson , Riko Noormets , Christof Pearce , Igor Semilietov , Christian Stranne1,2,5, Martin Jakobsson1,2. 1 Department of Geological Sciences, Stockholm University, Stockholm, 106 91, Sweden 2 Bolin Centre for Climate Research, Stockholm University, Stockholm, Sweden 10 3 US Geological Survey MS926A, Reston, Virginia, 20192, USA 4 Department of Physical Geography (NG), Stockholm University, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden 5 Center for Coastal and Ocean Mapping, University of New Hampshire, New Hampshire 03824, USA 6 Department of Meteorology, Stockholm University, Stockholm, 106 91, Sweden 7 University Centre in Svalbard (UNIS), P O Box 156, N-9171 Longyearbyen, Svalbard 15 8 Department of Geoscience, Aarhus University, Aarhus, 8000, Denmark 9 Pacific Oceanological Institute, Far Eastern Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences, 690041 Vladivostok, Russia 10 Tomsk National Research Polytechnic University, Tomsk, Russia Correspondence to: Matt O’Regan ([email protected]) 20 Abstract. Ice sheets extending over parts of the East Siberian continental shelf have been proposed during the last glacial period, and during the larger Pleistocene glaciations. The sparse data available over this sector of the Arctic Ocean has left the timing, extent and even existence of these ice sheets largely unresolved. -

Equine Laminitis Managing Pasture to Reduce the Risk

Equine Laminitis Managing pasture to reduce the risk RIRDCnew ideas for rural Australia © 2010 Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation. All rights reserved. ISBN 978 1 74254 036 8 ISSN 1440-6845 Equine Laminitis - Managing pasture to reduce the risk Publication No. 10/063 Project No.PRJ-000526 The information contained in this publication is intended for general use to assist public knowledge and discussion and to help improve the development of sustainable regions. You must not rely on any information contained in this publication without taking specialist advice relevant to your particular circumstances. While reasonable care has been taken in preparing this publication to ensure that information is true and correct, the Commonwealth of Australia gives no assurance as to the accuracy of any information in this publication. The Commonwealth of Australia, the Rural Industries Research and Development Corporation (RIRDC), the authors or contributors expressly disclaim, to the maximum extent permitted by law, all responsibility and liability to any person, arising directly or indirectly from any act or omission, or for any consequences of any such act or omission, made in reliance on the contents of this publication, whether or not caused by any negligence on the part of the Commonwealth of Australia, RIRDC, the authors or contributors. The Commonwealth of Australia does not necessarily endorse the views in this publication. This publication is copyright. Apart from any use as permitted under the Copyright Act 1968, all other rights are reserved. However, wide dissemination is encouraged. Requests and inquiries concerning reproduction and rights should be addressed to the RIRDC Publications Manager on phone 02 6271 4165. -

Remarks by Mead Treadwell Chair, U.S. Arctic Research Commission

Remarks by Mead Treadwell Chair, U.S. Arctic Research Commission International Arctic Fisheries Conference Institute of the North/Hotel Captain Cook Anchorage, Alaska – October 19, 2009 Arctic Fisheries: five things we should commit to now Thank you, Ben, for your introduction, and for pulling this conference together. Some of you know Ben Ellis, some of you may not. Until a few weeks ago, I called him ‘boss’: I’d recruited him, and he’d succeeded me as managing director of the Institute of the North. Ben, you’ve done a magnificent job for Alaskans, for the Arctic, for the country by doing what Governor Wally Hickel taught us both to do: convene a learned conversation to help Northerners address what’s strategic, and to find a common voice. Northerners everywhere can thank you for what you’ve done to advance fisheries, shipping, aviation safety, our common security, and sustainable energy in your work. The tone and tenor of Alaska’s political conversation – and talk throughout the Arctic – is calmer, cooler, and collected because of your dedicated work, including one of the Institute’s hallmark programs, an annual “Alaska Dialogue” policy conference at the foot of North America’s tallest mountain, Denali. Don’t get me wrong – I’m not saying Ben himself is always calm or cool or collected! Try bringing bananas on his fishing boat! Ben, every time we see your temper, it has been to get us all to chip in, to push us all forward, and forward we have come. Thanks. I also want to recognize Ambassador David Balton who is with us this week. -

Natural Variability of the Arctic Ocean Sea Ice During the Present Interglacial

Natural variability of the Arctic Ocean sea ice during the present interglacial Anne de Vernala,1, Claude Hillaire-Marcela, Cynthia Le Duca, Philippe Robergea, Camille Bricea, Jens Matthiessenb, Robert F. Spielhagenc, and Ruediger Steinb,d aGeotop-Université du Québec à Montréal, Montréal, QC H3C 3P8, Canada; bGeosciences/Marine Geology, Alfred Wegener Institute Helmholtz Centre for Polar and Marine Research, 27568 Bremerhaven, Germany; cOcean Circulation and Climate Dynamics Division, GEOMAR Helmholtz Centre for Ocean Research, 24148 Kiel, Germany; and dMARUM Center for Marine Environmental Sciences and Faculty of Geosciences, University of Bremen, 28334 Bremen, Germany Edited by Thomas M. Cronin, U.S. Geological Survey, Reston, VA, and accepted by Editorial Board Member Jean Jouzel August 26, 2020 (received for review May 6, 2020) The impact of the ongoing anthropogenic warming on the Arctic such an extrapolation. Moreover, the past 1,400 y only encom- Ocean sea ice is ascertained and closely monitored. However, its pass a small fraction of the climate variations that occurred long-term fate remains an open question as its natural variability during the Cenozoic (7, 8), even during the present interglacial, on centennial to millennial timescales is not well documented. i.e., the Holocene (9), which began ∼11,700 y ago. To assess Here, we use marine sedimentary records to reconstruct Arctic Arctic sea-ice instabilities further back in time, the analyses of sea-ice fluctuations. Cores collected along the Lomonosov Ridge sedimentary archives is required but represents a challenge (10, that extends across the Arctic Ocean from northern Greenland to 11). Suitable sedimentary sequences with a reliable chronology the Laptev Sea were radiocarbon dated and analyzed for their and biogenic content allowing oceanographical reconstructions micropaleontological and palynological contents, both bearing in- can be recovered from Arctic Ocean shelves, but they rarely formation on the past sea-ice cover.