Can Openness Mitigate the Effects of Weather Shocks? Evidence from India’S Famine Era

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Evidence from India's Famine Era." American Economic Review (2010) 100(2): 449–53

Can Openness Mitigate the Effects of Weather Fluctuations? Evidence from India’s Famine Era The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Burgess, Robin, and Dave Donaldson. "Can Openness Mitigate the Effects of Weather Shocks? Evidence from India's Famine Era." American Economic Review (2010) 100(2): 449–53. As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.2.449 Version Author's final manuscript Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/64729 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 CAN OPENNESS MITIGATE THE EFFECTS OF WEATHER SHOCKS? EVIDENCE FROM INDIA'S FAMINE ERA ROBIN BURGESS AND DAVE DONALDSON A weakening dependence on rain-fed agriculture has been a hallmark of the economic transformation of countries throughout history. Rural citizens in developing countries to- day, however, remain highly exposed to fluctuations in the weather. This exposure affects the incomes these citizens earn and the prices of the foods they eat. Recent work has docu- mented the significant mortality stress that rural households face in times of adverse weather (Robin Burgess, Olivier Deschenes, Dave Donaldson & Michael Greenstone 2009, Masayuki Kudamatsu, Torsten Persson & David Stromberg 2009). Famines|times of acutely low nominal agricultural income and acutely high food prices|are an extreme manifestation of this mapping from weather to death. Lilian. C. A. Knowles (1924) describes these events as \agricultural lockouts" where both food supplies and agricultural employment, on which the bulk of the rural population depends, plummet. The result is catastrophic with widespread hunger and loss of life. -

Railroads and the Demise of Famine in Colonial India ⇤

Railroads and the Demise of Famine in Colonial India ⇤ Robin Burgess LSE and NBER Dave Donaldson Stanford and NBER March 2017 Abstract Whether openness to trade can be expected to reduce or exacerbate the equilibrium exposure of real income to productivity shocks remains theoretically ambiguous and empirically unclear. In this paper we exploit the expansion of railroads across India between 1861 to 1930—a setting in which agricultural technologies were rain-fed and risky, and regional famines were commonplace—to examine whether real incomes be- came more or less sensitive to rainfall shocks as India’s district economies were opened up to domestic and international trade. Consistent with the predictions of a Ricardian trade model with multiple regions we find that the expansion of railroads made local prices less responsive, local nominal incomes more responsive, and local real incomes less responsive to local productivity shocks. This suggests that the lowering of trans- portation costs via investments in transportation infrastructure played a key role in raising welfare by lessening the degree to which productivity shocks translated into real income volatility. We also find that mortality rates became significantly less respon- sive to rainfall shocks as districts were penetrated by railroads. This finding bolsters the view that growing trade openness helped protect Indian citizens from the negative impacts of productivity shocks and in reducing the incidence of famines. ⇤Correspondence: [email protected] and [email protected] We thank Richard Blundell, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and seminar participants at Bocconi University and the 2012 Nemmers Prize Confer- ence (at Northwestern) for helpful comments. -

Courtesans in Colonial India Representations of British Power Through Understandings of Nautch-Girls, Devadasis, Tawa’Ifs, and Sex-Work, C

Courtesans in Colonial India Representations of British Power through Understandings of Nautch-Girls, Devadasis, Tawa’ifs, and Sex-Work, c. 1750-1883 by Grace E. S. Howard A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in History Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Grace E. S. Howard, May, 2019 ABSTRACT COURTESANS IN COLONIAL INDIA REPRESENTATIONS OF BRITISH POWER THROUGH UNDERSTANDINGS OF NAUTCH-GIRLS, DEVADASIS, TAWA’IF, AND SEX-WORK, C. 1750-1883 Grace E. S. Howard Advisors: University of Guelph Dr. Jesse Palsetia Dr. Norman Smith Dr. Kevin James British representations of courtesans, or nautch-girls, is an emerging area of study in relation to the impact of British imperialism on constructions of Indian womanhood. The nautch was a form of dance and entertainment, performed by courtesans, that originated in early Indian civilizations and was connected to various Hindu temples. Nautch performances and courtesans were a feature of early British experiences of India and, therefore, influenced British gendered representations of Indian women. My research explores the shifts in British perceptions of Indian women, and the impact this had on imperial discourses, from the mid-eighteenth through the late nineteenth centuries. Over the course of the colonial period examined in this research, the British increasingly imported their own social values and beliefs into India. British constructions of gender, ethnicity, and class in India altered ideas and ideals concerning appropriate behaviour, sexuality, sexual availability, and sex-specific gender roles in the subcontinent. This thesis explores the production of British lifestyles and imperial culture in India and the ways in which this influenced their representation of courtesans. -

Introduction to India and South Asia

Professor Benjamin R. Siegel Lecture, Fall 2018 History Department, Boston University T, Th, 12:30-1:45, CAS B20 [email protected] Office Hours: T: 11:00-12:15 Office: Room 205, 226 Bay State Road Th: 11:00-12:15, 2:00-3:15 & by appt. HI234: Introduction to India and South Asia Course Description It is easy to think of the Indian subcontinent, home of nearly 1.7 billion people, as a region only now moving into the global limelight, propelled by remarkable growth against a backdrop of enduring poverty, and dramatic contestations over civil society. Yet since antiquity, South Asia has been one of the world’s most dynamic crossroads, a place where cultures met and exchanged ideas, goods, and populations. The region was the site of the most prolonged and intensive colonial encounter in the form of Britain’s Indian empire, and Indian individuals and ideas entered into long conversations with counterparts in Europe, the Middle East, East and Southeast Asia, and elsewhere. Since India’s independence and partition into two countries in 1947, the region has struggled to overcome poverty, disease, ethnic strife and political conflict. Its three major countries – India, Pakistan, and Bangladesh – have undertaken three distinct experiments in democracy with three radically divergent outcomes. Those countries’ large, important diaspora populations and others have played important roles in these nation’s development, even as the larger world grows more aware of how important South Asia remains, and will become. 1 HI 234 – Course Essentials This BU Hub course is a survey of South Asian history from antiquity to the present, focusing on the ideas, encounters, and exchanges that have formed this dynamic region. -

Confidential Manuscript Submitted to Geophysical Research Letters 1

Confidential manuscript submitted to Geophysical Research Letters 1 Drought and famine in India , 1870 - 2016 2 3 Vimal Mishra 1 , Amar Deep Tiwari 1 , Reepal Shah 1 , Mu Xiao 2 , D.S. Pai 3 , Dennis Lettenmaier 2 4 5 1. Civil Engineering, Indian Institute of Technology, Gandhinagar, India 6 2. Department of Geography, University of California, Los Angeles, USA 7 3. India Meteorological Department (IMD), Pune 8 9 Abstract 10 11 Millions of people died due to famines caused by droughts and crop failures in India in the 19 th and 12 20 th centuries . However, the relationship of historical famines with drought is complic ated and not 13 well understood in the context of the 19 th and 20 th - century events. Using station - based observations 14 and simulations from a hydrological model, we reconstruct soil moisture ( agricultural ) drought in 15 India for the period 1870 - 2016. We show that over this century and a half period , India experienced 16 seven major drought periods (1876 - 1882, 1895 - 1900, 1908 - 1924, 1937 - 1945, 1982 - 1990, 1997 - 17 2004, and 2011 - 2015) based on severity - area - duration (SAD) analysis of reconstructed soil 18 moisture. Out of six major famines (1873 - 74, 1876, 1877, 1896 - 97, 1899, and 1943) that occurred 19 during 1870 - 2016 , five are linked to soil moisture drought , and one (1943) was not. On the other 20 hand, five major droughts were not linked with famine, and three of tho se five non - famine droughts 21 occurred after Indian Independence in 1947. Famine deaths due to droughts have been significantly 22 reduced in modern India , h owever, ongoing groundwater storage depletion has the potential to 23 cause a shift back to recurrent famines . -

British Humanitarian Political Economy and Famine in India, 1838–1842

This is a repository copy of British Humanitarian Political Economy and Famine in India, 1838–1842. White Rose Research Online URL for this paper: http://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/148482/ Version: Accepted Version Article: Major, A (2020) British Humanitarian Political Economy and Famine in India, 1838–1842. Journal of British Studies, 59 (2). pp. 221-244. ISSN 0021-9371 https://doi.org/10.1017/jbr.2019.293 © The North American Conference on British Studies, 2020. This is an author produced version of an article published in Journal of British Studies. Uploaded in accordance with the publisher's self-archiving policy. Reuse Items deposited in White Rose Research Online are protected by copyright, with all rights reserved unless indicated otherwise. They may be downloaded and/or printed for private study, or other acts as permitted by national copyright laws. The publisher or other rights holders may allow further reproduction and re-use of the full text version. This is indicated by the licence information on the White Rose Research Online record for the item. Takedown If you consider content in White Rose Research Online to be in breach of UK law, please notify us by emailing [email protected] including the URL of the record and the reason for the withdrawal request. [email protected] https://eprints.whiterose.ac.uk/ Wordcount: 10,159 (12,120 with footnotes) British Humanitarian Political Economy and Famine in India, 1838-42. In the spring of 1837 the colonial press in India began to carry disturbing accounts of growing agricultural distress in the Agra region of north-central India.1 Failed rains and adverse market conditions had created a fast deteriorating situation as peasant cultivators increasingly found themselves unable to access to enough food to eat. -

Prostitutes As an Outeast Group in Colonial India

The Queens' Daughters: Prostitutes as an Outeast Group in Colonial India Ratnabali Chatterjee R 1992: 8 Report Chr. Michelsen Institute -I Department of Social Science and Development ISSN 0803-0030 The Queens' Daughters: Prostitutes as an Outeast Group in Colonial India Ratnabali Chatterjee R 1992: 8 Bergen, December 1992 .1. DepartmentCHR. MICHELSEN of Social Science INSTITUTE and Development Report 1992: 8 The Queens' Daughters: Prostitutes as an Outeast Group in Colonial India Ratnabali Chatterjee Bergen, December 1992. 34 p. Summary: The report historically traces the sodal constnction of the Indian prostitute, which misrepresented and degraded the imagery of an accomplished courtesan and arstic entertainer to the degraded western image of a prostitute. The first part deals with the methods and motivations of the colonial government in constning Indian prostitutes as a separate and distinet group. The secondpar analyses the reactions and effects the colonial discourse had on indigenous elites, and ends with a presentation of the imagery surrounding the Indian prostitute in Bengali popular literature of the time. Sammendrag: Rapporten er en historisk analyse av bakgrnnen for ideen om indisk prostitusjon, og dokumenterer hvordan grpper av høyt respekterte og anerkjente arister ble mistolket og sitert. Den førsten delen dokumenter motivene til og metodene som kolonimyndighetene benyttet for å skile ut prostituerte som en egen grppe. Den andre og siste delen dokumenterer og analyserer den indiske eliten sine reaksjoner på dette og anskueliggjør debatten som fulgte med eksempler på presentasjon av den prostituerte i bengalsk populær litteratur. Indexing terms: Stikkord: Women Kvinner Prostitution Prostitusjon Colonialism Kolonialisme India India To be orderedfrom Chr. -

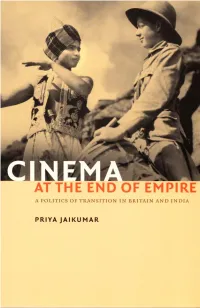

Cinema at the End of Empire: a Politics of Transition

cinema at the end of empire CINEMA AT duke university press * Durham and London * 2006 priya jaikumar THE END OF EMPIRE A Politics of Transition in Britain and India © 2006 Duke University Press * All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper Designed by Amy Ruth Buchanan Typeset in Quadraat by Tseng Information Systems, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data and permissions information appear on the last printed page of this book. For my parents malati and jaikumar * * As we look back at the cultural archive, we begin to reread it not univocally but contrapuntally, with a simultaneous awareness both of the metropolitan history that is narrated and of those other histories against which (and together with which) the dominating discourse acts. —Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism CONTENTS List of Illustrations xi Acknowledgments xiii Introduction 1 1. Film Policy and Film Aesthetics as Cultural Archives 13 part one * imperial governmentality 2. Acts of Transition: The British Cinematograph Films Acts of 1927 and 1938 41 3. Empire and Embarrassment: Colonial Forms of Knowledge about Cinema 65 part two * imperial redemption 4. Realism and Empire 107 5. Romance and Empire 135 6. Modernism and Empire 165 part three * colonial autonomy 7. Historical Romances and Modernist Myths in Indian Cinema 195 Notes 239 Bibliography 289 Index of Films 309 General Index 313 ILLUSTRATIONS 1. Reproduction of ‘‘Following the E.M.B.’s Lead,’’ The Bioscope Service Supplement (11 August 1927) 24 2. ‘‘Of cource [sic] it is unjust, but what can we do before the authority.’’ Intertitles from Ghulami nu Patan (Agarwal, 1931) 32 3. -

The Art of Imperial Entanglements Nautch Girls on the British Canvas and Stage in the Long Nineteenth Century

The Art of Imperial Entanglements Nautch Girls on the British Canvas and Stage in the Long Nineteenth Century Inauguraldissertation zur Erlangung der Doktorwürde der Philosophischen Fakultät der Ruprecht-Karls-Universität Heidelberg vorgelegt von Zara Barlas, M.A. Erstgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Monica Juneja Zweitgutachterin: Prof. Dr. Dorothea Redepenning Heidelberg, den 6. Mai 2018 Contents Acknowledgements .......................................................................................................... 5 I Introduction .................................................................................................................. 6 Art and Imperialism ........................................................................................................... 9 Hypothesis and Premise ..................................................................................................21 Disciplinary Theory & Methods in the Arts: A Brief Overview ........................................22 Historical Processes .........................................................................................................33 Overview ..........................................................................................................................42 II Framing an Enigma: The Nautch Girl in Victorian Britain .............................................. 44 Defining the Nautch Girl ..................................................................................................45 The Nautch-Girl Genre .....................................................................................................59 -

Agricultural Sciences in India and Struggle Against Famine, Hunger and Malnutrition

ARTICLES IJHS | VOL 54.3 | SEPTEMBER 2019 Agricultural Sciences in India and Struggle against Famine, Hunger and Malnutrition Rajendra Prasad∗ Ex-ICAR National Professor, Indian Agricultural Research Institute, New Delhi; Corresponding address: 6695 Meghan Rose Way, East Amherst, NY 14051, USA (Received 09 January 2019) Abstract India has a history of famines and hunger. However, starting with the British initiatives in the beginning of the 20th century, followed by US AID assistance and help after its independence in 1947, and later with its own massive developments in agricultural research under the Indian Council of Agricultural Research (ICAR), education and extension, India has now achieved self-sufficiency in food grains. Government of India has also developed a well-organized public distribution system (PDS) for distribution of food grains especially for below poverty line people (BPL). There has been no famine in India after it gained independence in 1947. In addition to food grains, agricultural science and technology has also helped India in taking strides in the production of fruits and vegetables, milk and fisheries and meat. India thus presents as an excellent example of application of agricultural sciences toward a country’s development to other developing nations of the world and work in this direction in collaboration with USAID is in progress. Key words: Etawah Project, Famine Commission Reports (FCRs), Global hunger index (GHI), Grey or Blue Revolution, Imperial Department of Agriculture, Indian Agricultural Research Institute (IARI), Mexican dwarf wheats, AB Stewart Report, US AID, White Revolution, Yellow Revolution. 1 Introduction were frequent in the past and people had to struggle for food. -

Famine Prevention in India

FAMINE PREVENTION IN INDIA Jean February 1988 This is a revised version of a paper presented at the World Institute for Development Economics Research (WIDER, Helsinki) in July 1986. The final version is to appear in Dreze, J. and Sen, A. (eds.). Hunger: Economics and Policy (forthcoming, Clarendon Press). I am grateful to WIDER for financial support. DEP No.3 The Development Economics Research Programme January 1988. Suntory-Toyota International Centre for Economics and Related Disciplines 10 Portugal Street London WC2A 2HD Tel : 01-405-7686, ext.3290 2 Acknowledgments Preparing this paper has been for me a marvellous opportunity to benefit from the thoughts, comments and guidance of a very large number of people. For their friendly and patient help, I wish to express my hearty thanks to: 'Ehtisham Ahmad, Harold Alderman, Arjun Appadurai, David Arnold, Kaushik Basu, A.N. Batabyal, Nikilesh Bhattacharya, Crispin Bates, Sulabha Brahme, Robert Chambers, Marty Chen, V.K. Chetty, Stephen Coate, Lucia da Corta, Nigel Crook, Parviz Dabir-Alai, Guvant Desai, Meghnad Desai, V.D. DeiShpande, Steve Devereux, Ajay Dua, Tim Dyson, Hugh Goyder, S. Guhan, Deborah Guz, Barbara Harriss, Judith Heyer, Simon Hunt, N.S. Iyengar, N.S. Jodha, Jane Knight, Gopalakrishna Kumar, Jocelyn Kynch, Peter Lanjouw, Michael Lipton, John Levi, Michelle McAlpin, John Melior, B.S. Minhas, Mark Mullins, Vijay Nayak, Elizabeth Oughton, Kirit Parikh, Pravin Patkar, Jean-Philippe Platteau, Amrita Rangasami, N. P. Rao, J. G. Sastry, John Seaman, Amartya Sen, Kailash Sharma, P.V. Srinivasan, Elizabeth Stamp, Nicholas Stern, K. Subbarao, P. Subramaniam, V. Subramaniam, Peter Svedberg, Jeremy Swift, Martin Ravallion, David Taylor, Suresh Tendulkar, A.M. -

UNTOUCHABLE FREEDOM a Social History of a Dalit Community

UNTOUCHABLE FREEDOM UNTOUCHABLE FREEDOM A Social History of a Dalit Community VVVijay Prashad vi / Acknowledgements Contents Introduction of illustrations viii Chapter 1. Mehtars ix Chapter 2. Chuhras 25 Chapter 3. Sweepers 46 Chapter 4. Balmikis 65 Chapter 5. Harijans 112 Chapter 6. Citizens 135 Epilogue 166 Glossary 171 Archival Sources 173 Index 175 List of Illustrations Sweepers Outside the Town Hall 8 Entrance to Valmiki Basti 33 Gandhi in Harijan Colony (Courtesy: Nehru Memorial Museum and Library) 114 Portrait of Bhoop Singh 139 Introduction Being an Indian, I am a partisan, and I am afraid I cannot help taking a partisan view. But I have tried, and I should like you to try to consider these questions as a scientist impartially examining facts, and not as a nationalist out to prove one side of the case. Nationalism is good in its place, but it is an unreliablev friend and vanvunsafe vhistorian. (Jawaharlal Nehru, 14 December 1932).1 In the aftermath of the pogrom against the Sikhs in Delhi (1984), in which 2500 people perished in a few days, reports filled the capital of the assail- ants and their motives. It was clear from the very first that this was no disorganized ‘riot’ and that the organized violence visited upon Sikhs was engineered by the Congress (I) to avenge the assassination of Indira Gandhi. Of the assailants, we only heard rumours, that they came from the outskirts of the city, from those ‘urban villages’ inhabited by Jats and Gujjars as well as dalits (untouchables) resettled there during the Na- tional Emergency (1975–7).