Agricultural Sciences in India and Struggle Against Famine, Hunger and Malnutrition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Chapter-3 Commercialization of Agriculture

Chapter-3 Commercialization of agriculture Commercialization of Agriculture: - 1. Meaning of Commercialization of Agriculture 2. Phases of Commercialization of Agriculture 3. Causes 4. Consequences. 1. Meaning of Commercialization of Agriculture By commercialization of agriculture we mean production of agricultural crops for sale in the market, rather than for family consumption. For marketization of agricultural products thus ‘surplus’ of production over consumption is required. But agriculture at that time was merely of the subsistence type. It had not been a consequence of conscious response of peasants to the market forces. Thus, the concept of surplus was partly irrelevant. It was the social organisation but not entrepreneurial role of the peasants that determined the marketed surplus. The decision to cultivate commercial crops was usually determined by the requirements of subsistence farming of peasants. Thus, commercial agriculture in India had not been the product of an “allocative efficiency of peasants”. Production decision was entirely of peasants and profits (if any) from the marketed items were reaped by peasants. Under the impact of commercial revolution that began with the beginning of the Civil War (1861-1865) in North America, farmers’ products were brought into the sphere of both internal and international trade. Farmers were forced to sell their producers to meet the revenue needs of the alien government as well as urban demand. Peasants had to cough up some surplus at least for the market since money had become indispensable to them. Thus commercialization of agriculture was not a spontaneous one 2 Phases of Commercialization of Agriculture There were three major types of agricultural commercialization in India. -

Below Is a List of Nonprofits That Received Donations Through UWATX During the 2012 Campaign Year

Below is a list of nonprofits that received donations through UWATX during the 2012 Campaign Year. Nonprofits with (*) also receive UWATX grant funding. 100 Club, Inc. 4 Paws For Ability Inc 4-H Clubs & Affiliated 4-H Organizations A Childs Hope Fund A Community for Education A Glimmer of Hope Foundation A Soldier's Child Inc. A Wish With Wings, Inc. A Womans Haven Inc Aaron Diamond AIDS Research Center Abandoned Childrens Fund Abilene Boys Ranch Abilene Christian University Ability Connection Texas (ACT) Abortion Access Project, Inc. Abraham Fund, Inc. Abundant Life Apostolic Assembly Abused Children's Fund, Inc. Access Fund ACCION International ACE Academy Achievement Ceneter of Texas Aclu Foundation Of Texas, Inc. Action Against Hunger USA Adopt a Platoon Adopt-A-Beach Program Texas General Land Office Adopt-A-Soldier Platoon Inc. Adoption Affiliates Inc Adoption and Humanitarian Aid Adoptions by Cradle of Hope Adult Protective Services Partners Inc Adventist Development And Relief Agency International Adventures in Health, Education & Agricultural Development Inc. Advocacy Center for Children of El Paso Advocacy Center for Crime Victims and Children Advocacy Project Affordable Companion Animal Neutering Afghan Health and Development Services Africa AIDS Watch Africa Classroom Connection African Children's Fund for Orphaned & Abandoned Children African Childrens Haven African Infectious Disease Village Clinics Inc African Medical & Research Foundation, Inc. African Solutions to African Problems African Wildlife Foundation African-American Aids Policy & Training Institute Dba, Black Aids Institute Africare AGE of Central Texas Aggieland Pregnancy Outreach Inc. Aging and Disabilities Charities of America Inc Aid for Africa, Inc. Aid for African Catholic Missions Aid for AIDS International, Inc. -

Evidence from India's Famine Era." American Economic Review (2010) 100(2): 449–53

Can Openness Mitigate the Effects of Weather Fluctuations? Evidence from India’s Famine Era The MIT Faculty has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters. Citation Burgess, Robin, and Dave Donaldson. "Can Openness Mitigate the Effects of Weather Shocks? Evidence from India's Famine Era." American Economic Review (2010) 100(2): 449–53. As Published http://dx.doi.org/10.1257/aer.100.2.449 Version Author's final manuscript Citable link http://hdl.handle.net/1721.1/64729 Terms of Use Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 3.0 CAN OPENNESS MITIGATE THE EFFECTS OF WEATHER SHOCKS? EVIDENCE FROM INDIA'S FAMINE ERA ROBIN BURGESS AND DAVE DONALDSON A weakening dependence on rain-fed agriculture has been a hallmark of the economic transformation of countries throughout history. Rural citizens in developing countries to- day, however, remain highly exposed to fluctuations in the weather. This exposure affects the incomes these citizens earn and the prices of the foods they eat. Recent work has docu- mented the significant mortality stress that rural households face in times of adverse weather (Robin Burgess, Olivier Deschenes, Dave Donaldson & Michael Greenstone 2009, Masayuki Kudamatsu, Torsten Persson & David Stromberg 2009). Famines|times of acutely low nominal agricultural income and acutely high food prices|are an extreme manifestation of this mapping from weather to death. Lilian. C. A. Knowles (1924) describes these events as \agricultural lockouts" where both food supplies and agricultural employment, on which the bulk of the rural population depends, plummet. The result is catastrophic with widespread hunger and loss of life. -

Railroads and the Demise of Famine in Colonial India ⇤

Railroads and the Demise of Famine in Colonial India ⇤ Robin Burgess LSE and NBER Dave Donaldson Stanford and NBER March 2017 Abstract Whether openness to trade can be expected to reduce or exacerbate the equilibrium exposure of real income to productivity shocks remains theoretically ambiguous and empirically unclear. In this paper we exploit the expansion of railroads across India between 1861 to 1930—a setting in which agricultural technologies were rain-fed and risky, and regional famines were commonplace—to examine whether real incomes be- came more or less sensitive to rainfall shocks as India’s district economies were opened up to domestic and international trade. Consistent with the predictions of a Ricardian trade model with multiple regions we find that the expansion of railroads made local prices less responsive, local nominal incomes more responsive, and local real incomes less responsive to local productivity shocks. This suggests that the lowering of trans- portation costs via investments in transportation infrastructure played a key role in raising welfare by lessening the degree to which productivity shocks translated into real income volatility. We also find that mortality rates became significantly less respon- sive to rainfall shocks as districts were penetrated by railroads. This finding bolsters the view that growing trade openness helped protect Indian citizens from the negative impacts of productivity shocks and in reducing the incidence of famines. ⇤Correspondence: [email protected] and [email protected] We thank Richard Blundell, Chang-Tai Hsieh, and seminar participants at Bocconi University and the 2012 Nemmers Prize Confer- ence (at Northwestern) for helpful comments. -

Supply Chain Management of Indian Agriculture Industry: an Exploratory Study

Global Journal of Enterprise Information System DOI: 10.18311/gjeis/2018/20048 Supply Chain Management of Indian Agriculture Industry: An Exploratory Study Nitu Ranjan Agarwal1* and Anurag Saxena2 1Department of Management Studies, Rajarshi School of Management and Technology, UP College, India; [email protected] 2School of Management Studies, IGNOU, Maidan Garhi, New Delhi, India; [email protected] Abstract Indian Agriculture/Agro Industry (IAI) is an integral part of Indian society and economy. Approximately half of the total population relies on this industry as a principle source of income and it contributes around 14% of India’s GDP. Indian food business has increased to US$ 250 billion in 2015 as compared to US$ 220 billion in the year 2009 and expected to grow further rapidly in the next ten years. Indian Agriculture is a world leader in terms of production of many product categories As a result, on one hand engagement of huge population, rising demand, farm mechanization, increase in global markets, etc., offer huge potential for this industry. On the other hand, it faces many severe problems. Producers of agro products are getting merely 30–35 per cent of the market price in most of the cases due to lack of supply chain practices. Annual wastages of agricultural output are also very high which in monetary term sums up to around Rs 90,000 Crore. This wastage is mainly due to inadequate supply chain infrastructure. The objective of this paper is to highlight the present scenario of Indian Agricultural Industry in terms of prospects and explores various supply chain related issues of this industry. -

Social Concern

Social Concern Unit 2 - Hinduism Teacher’s advisory notes on ‘Social Concern’. Food For Life ISKCON ‘Uniting the World through Pure Food’ “Food for Life projects span the globe and all have unique local aims and objectives. However, all Food for Life projects will adhere to the following principles as part of their overall strategy. • Welfare: To provide pure plant-based meals to the disadvantaged, malnourished and victims of disaster (natural or manmade), and wherever there is a need in the world. • Hospitality: To revive the ancient Vedic culture of spiritual hospitality, and to teach people by example, that there is spiritual equality among all beings. • Non-Violence: To reduce the amount of animals slaughtered for food, by giving as many people as possible the higher taste of “karma-free” plant-based meals. • Health: To teach about the value of plant-based meals for improving body and mind health. • Education: To teach the art and science of food yoga as an integral part of consciousness development.” (https://ffl.org/about/aims-and-objectives/ “With roots dating back to 1974, Food for Life Global is an international network of vegan food reliefs, health, wellness and education services. Our mission is to create peace and prosperity in the world through the liberal distribution of pure food prepared with loving intention.” (https://ffl.org/) “No one within ten miles of our temple should go hungry”. A.C. Bhaktivedanta Swami Prabhupada. (https://ffl.org/about/philosophy/) “Such selfless gestures of hospitality were common in the village life of ancient India. The religious householders of the Vedic times saw themselves as providers for all living beings, including the animals. -

The Agriculture-Nutrition Disconnect in India: What Do We Know

IFPRI Discussion Paper 01187 June 2012 The Agriculture-Nutrition Disconnect in India What Do We Know? Stuart Gillespie Jody Harris Suneetha Kadiyala Poverty, Health, and Nutrition Division INTERNATIONAL FOOD POLICY RESEARCH INSTITUTE The International Food Policy Research Institute (IFPRI) was established in 1975. IFPRI is one of 15 agricultural research centers that receive principal funding from governments, private foundations, and international and regional organizations, most of which are members of the Consultative Group on International Agricultural Research (CGIAR). PARTNERS AND CONTRIBUTORS IFPRI gratefully acknowledges the generous unrestricted funding from Australia, Canada, China, Denmark, Finland, France, Germany, India, Ireland, Italy, Japan, the Netherlands, Norway, the Philippines, South Africa, Sweden, Switzerland, the United Kingdom, the United States, and the World Bank. AUTHORS Stuart Gillespie, International Food Policy Research Institute Senior Research Fellow, Poverty, Health, and Nutrition Division Jody Harris, International Food Policy Research Institute Research Analyst, Poverty, Health, and Nutrition Division Suneetha Kadiyala, International Food Policy Research Institute Research Fellow, Poverty, Health, and Nutrition Division Notices IFPRI Discussion Papers contain preliminary material and research results. They have been peer reviewed, but have not been subject to a formal external review via IFPRI’s Publications Review Committee. They are circulated in order to stimulate discussion and critical comment; any opinions expressed are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the policies or opinions of IFPRI. Copyright 2012 International Food Policy Research Institute. All rights reserved. Sections of this material may be reproduced for personal and not-for-profit use without the express written permission of but with acknowledgment to IFPRI. -

Agricultural Situation in India Wages on Month to Month Basis

ISSN 0002-1679 P. Agri. 21-08-2015 Regn.No.:840 450 List of other Publications of the Directorate AAGGRRIICCUULLTTUURRAALL SSIITTUUAATTIIOONN IINN IINNDDIIAA Periodicals AUGUST, 2015 Agricultural Prices in India GENERAL SURVEY OF AGRICULTURE AGRO ECONOMIC RESEARCH Biotechnology in Agriculture: FARM SECTOR NEWS Potential,Performance and Concerns Agricultural Statistics at a Glance ARTICLES Loan Repayment Problem in India Agricultural Wages in India Institutional Credit for Agriculture in India since Reforms COMMODITY REVIEWS Foodgrains Economic Liberalisation and Agricultural Commercial Crops Cost of Cultivation of Principal Crops in India Productivity in North-East India TRENDS IN AGRICULTURE:Wages & Prices Decomposition Analyisis and acreage District-wise Area and Production of Principal Crops in India Response of Tur in Eastern Vidarbha Region of Maharashtra Farm Harvest Prices of Principal Crops in India Glimpses of Indian Agriculture Land Use Statistics at a Glance Copies are available at: The Controller of Publications, Civil Lines, Delhi-110054 PRINTED BY THE GENERAL MANAGER GOVERNMENT OF INDIA PRESS, MINTO ROAD, NEW DELHI-110002 AND PUBLISHED BY THE CONTROLLER OF PUBLICATIONS, DELHI-110054-2015 Editorial Board Chairman Sangeeta Verma Agricultural Situation Editor in India P. C. Bodh VOL. LXXII August, 2015 No. 5 Asstt. Economic Adviser Yogita Swaroop CONTENTS Economic Officer PAGES Prosenjit Das GENERAL SURVEY OF AGRICULTURE 1 Officials Associated in Preparation of the Publication FARM SECTOR NEWS 4 D.K. Gaur — Tech. Asstt. S.K. Kaushal — Tech. Asstt. (Printing) ARTICLES Uma Rani — Tech. Asstt. (Printing) V.M. Shobhana — P.A. Institutional Credit for Agriculture in India Since Reforms—Sini Thomas M & Mani K P 14 Cover Design Yogeshwari Tailor— Asstt. -

Awfw-12-Page-Booklet-Web

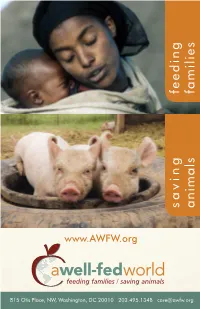

815 Otis Place, NW, Washington, DC 20010 202.495.1348 [email protected] 202.495.1348 20010 DC Washington, NW, Place, Otis 815 www.AWFW.org �������� ��������� �� ������� ������� s a v i n g feeding animals families what’sinside Table of Contents . .1 Welcome Letter . 2 About Global Grants . 3 Grant Winning Projects . 4 Ethiopia Focus . 5 India Focus . 6 Plants-4-Hunger Gifts . 7 Advocacy & Education . 8 Our Partners . 9 Why Support Us . 10 er ung -h 4 - s t n a ������������ l p �������� ����� Cover photo credits: Poplar Spring Animal Sanctuary’s rescued piglets by Mark Peters Photography. 1 Dear Friend, Thank you for your interest in A Well-Fed World and for sharing our dual-mission to feed families and save animals. We are a hunger relief and animal protection organization chipping away at two of the world’s most immense and unnecessary forms of suffering -- the suffering of people hungry from lack of food, and the suffering of animals used and abused for food. Our approach is positive and practical. In addition to our advocacy and programs promoting the benefits of plant-based diet and agriculture for global food security, we financially assist and partner with innovative, highly-effective projects to strengthen: vegan food and farming farm animal care and rescue outreach and community-building welcome & thank you We work bottom-up to produce immediate results for people and animals in need… and top-down with social justice leaders to create long-lasting, structural change. This booklet provides a glimpse at our work. I hope the unique and powerful results we achieve inspires you to stay connected by signing-up and/or donating at www.awfw.org. -

Dynamics and Determinants of Land Change in India: Integrating Satellite Data with Village Socioeconomics

Reg Environ Change DOI 10.1007/s10113-016-1068-2 ORIGINAL ARTICLE Dynamics and determinants of land change in India: integrating satellite data with village socioeconomics 1 2 3 2 Prasanth Meiyappan • Parth S. Roy • Yeshu Sharma • Reshma M. Ramachandran • 4 5 1 Pawan K. Joshi • Ruth S. DeFries • Atul K. Jain Received: 11 April 2016 / Accepted: 12 October 2016 Ó The Author(s) 2016. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract We examine the dynamics and spatial determi- *23,810 km2 (1985–1995) to *25,770 km2 (1995–2005). nants of land change in India by integrating decadal land The gross forest gain also increased from *6000 km2 cover maps (1985–1995–2005) from a wall-to-wall analy- (1985–1995) to *7440 km2 (1995–2005). Overall, India sis of Landsat images with spatiotemporal socioeconomic experienced a net decline in forest by *18,000 km2 (gross database for *630,000 villages in India. We reinforce our loss–gross gain) consistently during both decades. We results through collective evidence from synthesis of 102 show that the major source of forest loss was cropland case studies that incorporate field knowledge of the causes expansion in areas of low cropland productivity (due to soil of land change in India. We focus on cropland–fallow land degradation and lack of irrigation), followed by industrial conversions, and forest area changes (excludes non-forest development and mining/quarrying activities, and exces- tree categories including commercial plantations). We sive economic dependence of villages on forest resources. show that cropland to fallow conversions are prominently associated with lack of irrigation and capital, male agri- Keywords Land use change Á Drivers Á Causes Á cultural labor shortage, and fragmentation of land holdings. -

THE TEXTS, POLITICAL HISTORY and ADMINISTRATION Till C. 200 BC

History of Ancient India Volume III THE TEXTS, POLITICAL HISTORY AND ADMINISTRATION Till c. 200 BC Editors Dilip K. Chakrabarti and Makkhan Lal Vivekananda International Foundation New Delhi Aryan Books International New Delhi Cataloging in Publication Data—DK [Courtesy: D.K. Agencies (P) Ltd. <[email protected]>] History of ancient India / editors, Dilip K. Chakrabarti and Makkhan Lal. v. 3 cm. Contributed articles. Includes index. Contents: v. 3. The texts, political history and administration, till c. 200 BC. ISBN 9788173054822 1. India—History. 2. India—Politics and government. I. Chakrabarti, Dilip K., 1941- II. Makkhan Lal, 1954- III. Vivekananda International Foundation. DDC 954 23 ISBN: 978-81-7305-482-2 © Vivekananda International Foundation All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, utilised in any form or by any means, electronic and mechanical, including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system without prior permission of the authors and the publishers. Responsibility for statements made and visuals provided in the various papers rest solely with the contributors. The views expressed by individual authors are not necessarily those of the editors or of publishers. First Published in 2014 by Vivekananda International Foundation 3, San Martin Marg, Chanakyapuri, New Delhi - 110 021 Tel.: 24121764, 24106698; Fax: 91-11-43115450 E-mail: [email protected] www.vifindia.org in association with Aryan Books International Pooja Apartments, 4B, Ansari Road, New Delhi - 110 002 Tel.: 23287589, 23255799; Fax: 91-11-23270385 E-mail: [email protected] www.aryanbooks.co.in Designed and Printed in India at ABI Prints & Publishing Co., New Delhi. -

Hill Agriculture: Challenges and Opportunities∗

Ind. Jn. of Agri.Econ. Vol.66, No.1, Jan.-March 2011 Hill Agriculture: Challenges and Opportunities∗ Tej Partap† I PREFACE The Farmers Commission, “Serving farmers and saving farming” points to rising acute agricultural distress in the rainfed areas of the country, which also includes hilly areas. It lists five basic cause factors that are central to the crisis; unfinished land reforms, water scarcity, technology fatigue-access-adequacy, institutional support and opportunities for marketing. While working for the National Commission on Farmers as a hill agriculture expert, the contributions on the hill agriculture perspective, gathered knowledge and information about the Himalayan farmers’ state of affairs, of global experiences etc., made by me in compiling the hill farmers section of the main report of the commission also form the basis of this paper. The focus of this paper is on highlighting the challenges facing hill farmers and how they can be addressed. The paper first dwells on the scale and dimensions of the problems of hill farmers including the two most significant common concerns, increasing crop land scarcity and water scarcity to maintain agriculture on marginal lands. It explains various dimensions of the new thinking on marginal lands and implications. The next section, describes how similar problems were addressed by other nations successfully. To highlight the point that technological options are and have been available, the report cites examples of right technological hits of the Himalayan region. The last section analyses the opportunities to find solutions to the hill farmers’ distress. Much of the farming development efforts made in the hills in the past were based on the poor understanding of the hill/mountain conditions, resources, environment and the socio-cultural setting of the people.