MEIEA 2012 Color.Indd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 33, Number 04 (April 1915) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 4-1-1915 Volume 33, Number 04 (April 1915) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 33, Number 04 (April 1915)." , (1915). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/612 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. < PRICE 15? #1-50 PER YEAR THE ETUDE 241 PLAN NOW FOR MUSICAL PROSPERITY A MONTHLY JOURNAL FOR THE MUSICIAN, THE MUSIC STUDENT, AND ALL MUSIC LOVERS. efaf' Edited by James Francis Cooke Subscription Price, $1.50 per year in United States, THIS SEASON AND NEXT Alaska, Cuba, Porto Rico, Mexico, Hawaii, Philippines, or Panama, Guam, Tutuila, and the City of Shanghai. In Canada, $1.75 per year. In England and Colonies, 9 Shill¬ ings; in France, 11 Francs; in Germany, 9 Marks. All other countries, $2.22 per year. inner Liberal premiums and cash deductions are allowed for Sophocles was right, “Fortune is never on the side of the fainthearted.” The resolute, fore-sighted Ainei lLcl SI IV1USC I caurci s And the last thing she uminem music worker wins. -

The University of Chicago Scenes of Feeling: Music

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO SCENES OF FEELING: MUSIC AND THE IMAGINATION OF THE LIBERAL SUBJECT A DISSERTATION SUBMITTED TO THE FACULTY OF THE DIVISION OF THE HUMANITIES IN CANDIDACY FOR THE DEGREE OF DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY DEPARTMENT OF MUSIC BY DAN WANG CHICAGO, ILLINOIS DECEMBER 2017 © Copyright Dan Wang 2017 All rights reserved TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ……………………………………………………………….iv Abstract…………………………………………………………………………..vi List of Musical Examples ……………………………………………………….vii List of Figures…………………………………………………………………..viii Introduction Music, Feeling, and the Political 1 Chapter 1 Figaro and the Form of Shock 25 Chapter 2 Opera as a Form of Life: 64 The Ban on Love and Tannhäuser Chapter 3 The Structure of Romantic Affect: 114 Soundtracks and the Intimate Event Chapter 4 The Voice of Feeling 178 (Three Speeches by Colin Firth) Conclusion 218 Bibliography 223 iii ACKNOWLEDGMENTS These acknowledgments have to begin with Edmund J. Goehring and Emily Ansari, my Master’s advisors at Western University, who first made me think I could do a Ph.D. in musicology. The project has changed a lot since then, but I think (I hope) that its itinerary can still be traced. Enormous thanks are owed to my dissertation committee for providing the many different kinds of help that are needed to shape an impulse into a form. Martha Feldman, for good talks and for being a consistent supporter and reader over the years. David J. Levin, for timely boosts of confidence and for modeling the fun that academic life can have. Daniel Morgan, for unhesitant support and for his reassuringly pragmatic attitude in the last stretches. Lauren Berlant, who read with me and who didn’t give up on drafts. -

Download Joe Thomas If U Lose Her

Download joe thomas if u lose her LINK TO DOWNLOAD Love renuzap.podarokideal.ru never disappoints me. TZ Comment by Shin Banga. quality. TZ Comment by Sueli Moura. Heaven this melody is heaven. TZ Comment by AV. This is real R&B & the lyrics greatness! TZ Comment by JAY love this song. TZ Buy If You Lose Her. Coming Back Home Love and Freedom · I Believe in You My Name Is Joe · All Or Nothing Everything · Lets Stay Home Tonight Better Days · If You Lose Her Bridges · All That I Am All That I Am · Peep Show My Name Is Joe · Priceless And Then · Worst Case Scenario Signature · Somebody Gotta Be. Jun 24, · If You Lose Her Lyrics: So you think there's a flicker in your flame / But your regiment of a loving her is still the same / Forgotten holidays, forsaken little things / It means so much to her. Joe, Joe Thomas – Ride Wit U (MTV Version) ft. G-Unit. Joe – Stutter (Remix Video Without Film Footage) Joe – Stutter. Joe – The Love Scene. Joe – Treat Her Like A Lady. Joe – If You Lose Her (feat. Kseniya Simonova) [Full Sand Story] Joe feat. Kseniya Simonova – If You Lose Her (Official Video). Download Joe mp3. Joe download high quality complete mp3 albums. Login: Joe Thomas New Man mp3 download Year: Artist: Joe Quality: High Rating: Joe - Joe Thomas New Man album Track listing: No. Title: I lose myself in a daydream where I stand and say Don’t say yes, run away now. Complete song listing of Joe on renuzap.podarokideal.ru COVID Because of processes designed to ensure the safety of our employees, you may experience a delay in the shipping of your order. -

Untitled, It Is Impossible to Know

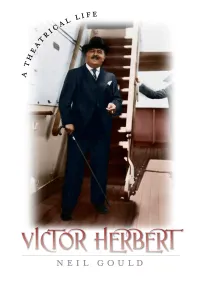

VICTOR HERBERT ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:09 PS PAGE i ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:09 PS PAGE ii VICTOR HERBERT A Theatrical Life C:>A<DJA9 C:>A<DJA9 ;DG9=6BJC>K:GH>INEG:HH New York ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE iii Copyright ᭧ 2008 Neil Gould All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gould, Neil, 1943– Victor Herbert : a theatrical life / Neil Gould.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8232-2871-3 (cloth) 1. Herbert, Victor, 1859–1924. 2. Composers—United States—Biography. I. Title. ML410.H52G68 2008 780.92—dc22 [B] 2008003059 Printed in the United States of America First edition Quotation from H. L. Mencken reprinted by permission of the Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore, Maryland, in accordance with the terms of Mr. Mencken’s bequest. Quotations from ‘‘Yesterthoughts,’’ the reminiscences of Frederick Stahlberg, by kind permission of the Trustees of Yale University. Quotations from Victor Herbert—Lee and J.J. Shubert correspondence, courtesy of Shubert Archive, N.Y. ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE iv ‘‘Crazy’’ John Baldwin, Teacher, Mentor, Friend Herbert P. Jacoby, Esq., Almus pater ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE v ................ -

Edith Wharton's Treatment of Love: a Study of Conventionality and Unconventionality in Her Fiction

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1967 Edith Wharton's Treatment of Love: a Study of Conventionality and Unconventionality in Her Fiction. Jo Agnew Mcmanis Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Mcmanis, Jo Agnew, "Edith Wharton's Treatment of Love: a Study of Conventionality and Unconventionality in Her Fiction." (1967). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1351. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1351 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 67*17,334 McMANIS, Jo Agnew, 1941- EDITH WHARTON'S TREATMENT OF LOVE: A STUDY OF CONVENTIONALITY AND UNCONVENTIONALITY IN HER FICTION. Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1967 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan EDITH WHARTON'S TREATMENT OP LOVE: A STUDY OF CONVENTIONALITY AND UNCONVENTIONALITY IN HER FICTION A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Jo Agnew McManis M.A., Louisiana State University, 1965 August, 1967 "Quotations from the following works by Edith Wharton are reprinted by special permission of Charles Scribner's Sons: THE HOUSE OF MIRTH, ETHAN FROME (Copyright 1911 Charles Scribner's Sons; renewal copyright 1939 Wm. -

9.1 GB # Artist Title Length 01 2Pac Do for Love 04:37

Total tracks number: 958 Total tracks length: 67:52:34 Total tracks size: 9.1 GB # Artist Title Length 01 2pac Do For Love 04:37 02 2pac Thug Mansion 03:32 03 2pac Thugz Mansion (Real) 04:06 04 2pac Wonder If Heaven Got A Ghetto 04:36 05 2pac Daz Kurupt Baby Dont Cry Remix 05:20 06 3lw No More 04:20 07 7 Mile Do Your Thing 04:49 08 8Ball & MJG You Don't Want Drama 04:32 09 112 Anywhere 04:04 10 112 Crazy over You 05:20 11 112 Cupid (Radio Mix) 04:08 12 112 Cupid 04:08 13 112 It's Over Now 04:00 14 112 Love You Like I Did 04:17 15 112 Only You (Slow Remix) 04:11 16 504 Boys Wobble Wobble Edited 03:42 17 504 Boys Wobble 03:38 18 702 Get It Together 04:50 19 702 Where My Girls At 02:45 20 1000 Clowns (Not The) Greatest Rapper 03:48 21 A Boogie Wit da Hoodie Drowning (feat. Kodak Black) 03:28 22 Aaliyah 4 Page Letter 04:50 23 Aaliyah Age Aint Nothing But A Number 03:37 24 Aaliyah Are You That Somebody 04:24 25 Aaliyah Dust Yourself Off 04:41 26 Aaliyah Hot Like Fire (Timbaland Remix 04:32 27 Aaliyah I Care 4 U 04:31 28 Aaliyah I Don't Wanna 04:12 29 Aaliyah If Your Girl Only Knew 04:50 30 Aaliyah More Than A Woman 03:48 31 Aaliyah One In A Million 04:29 32 Aaliyah Rock The Boat 04:33 33 Aaliyah The One I Gave My Heart To 03:52 34 Aaliyah Try Again 04:39 35 Aaliyah Ft. -

Tannhäuser: Poet and Legend COLLEGE of ARTS and SCIENCES Imunci Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures

Tannhäuser: Poet and Legend COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ImUNCI Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Tannhäuser: Poet and Legend With Texts and Translations of his Works j. w. thomas UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 77 Copyright © 1974 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Thomas, J. W.Tannhäuser: Poet and Legend: With Texts and Translations of his Works. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1974. doi: https://doi.org/10.5149/9781469658483_ Thomas Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Thomas, John Wesley. Title: Tannhäuser : poet and legend / by John Wesley Thomas. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 77. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1974] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: lccn 73-15986 | isbn 978-1-4696-5847-6 (pbk: alk. -

Film Music and Film Genre

Film Music and Film Genre Mark Brownrigg A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Stirling April 2003 FILM MUSIC AND FILM GENRE CONTENTS Page Abstract Acknowledgments 11 Chapter One: IntroductionIntroduction, Literature Review and Methodology 1 LiteratureFilm Review Music and Genre 3 MethodologyGenre and Film Music 15 10 Chapter Two: Film Music: Form and Function TheIntroduction Link with Romanticism 22 24 The Silent Film and Beyond 26 FilmTheConclusion Function Music of Film Form Music 3733 29 Chapter Three: IntroductionFilm Music and Film Genre 38 FilmProblems and of Genre Classification Theory 4341 FilmAltman Music and Genre and GenreTheory 4945 ConclusionOpening Titles and Generic Location 61 52 Chapter Four: IntroductionMusic and the Western 62 The Western and American Identity: the Influence of Aaron Copland 63 Folk Music, Religious Music and Popular Song 66 The SingingWest Cowboy, the Guitar and other Instruments 73 Evocative of the "Indian""Westering" Music 7977 CavalryNative and American Civil War WesternsMusic 84 86 PastoralDown andMexico Family Westerns Way 89 90 Chapter Four contd.: The Spaghetti Western 95 "Revisionist" Westerns 99 The "Post - Western" 103 "Modern-Day" Westerns 107 Impact on Films in other Genres 110 Conclusion 111 Chapter Five: Music and the Horror Film Introduction 112 Tonality/Atonality 115 An Assault on Pitch 118 Regular Use of Discord 119 Fragmentation 121 Chromaticism 122 The A voidance of Melody 123 Tessitura in extremis and Unorthodox Playing Techniques 124 Pedal Point -

JB DB by Artist

Song Title …. Artists Drop (Dirty) …. 216 Hey Hey …. 216 Baby Come On …. (+44) When Your Heart Stops Beating …. (+44) 96 Tears …. ? & The Mysterians Rubber Bullets …. 10cc The Things We Do For Love …. 10cc The Things We Do For Love …. 10cc Come See Me …. 112' Cupid …. 112' Damn …. 112' Dance With Me …. 112' God Knows …. 112' I'm Sorry (Interlude) …. 112' Intro …. 112' Just A Little While …. 112' Just A Little While …. 112' Last To Know …. 112' Let This Go …. 112' Let This Go …. 112' Love Me …. 112' My Mistakes …. 112' Nowhere …. 112' Only You …. 112' Peaches & Cream …. 112' Peaches & Cream (Clean) …. 112' Peaches & Cream (Dirty) …. 112' Peaches & Cream (Inst) …. 112' That's How Close We Are …. 112' U Already Know …. 112' U Already Know …. 112' We Goin' Be Alright …. 112' What If …. 112' What The H**l Do You Want …. 112' Why Can't We Get Along …. 112' You Already Know (Clean) …. 112' Dance Wit Me (Remix) …. 112' (w Beanie Segal) It's Over (Remix) …. 112' (w G.Dep & Prodigy) The Way …. 112' (w Jermaine Dupri) Hot & Wet (Dirty) …. 112' (w Ludacris) Love Me …. 112' (w Mase) Only You …. 112' (w Notorious B.I.G.) Anywhere (Remix) …. 112' (w Shyne) If I Can Hit …. 112' (w T.I.) If I Hit …. 112' (w T.I.) Closing The Club …. 112' (w Three 6 Mafia) Dunkie Butt …. 12 Gauge Lie To Me …. 12 Stones 1, 2, 3 Red Light …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Goody Goody Gumdrops …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Indian Giver …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simple Simon Says …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simple Simon Says …. -

Ytube Kill MTV Star

Escola das Artes da Universidade Católica Portuguesa Mestrado em Som e Imagem “YouTube Killed the MTV Star” Did Hip-Hop music videos become the blueprint for other genres of music videos in the digital age? Cinema e Audiovisual 2014 / 2015 João Pascoal Advisor: Sahra Kunz September 2015 “YouTube Killed the MTV Star” Did Hip-Hop music videos become the blueprint for other genres of music videos in the digital age? “YouTube Killed the MTV Star” Did Hip-Hop music videos become the blueprint for other genres of music videos in the digital age? João Pascoal September 2015 Dedication To Frank, for the idea. To my Father, for the cinema. To my Mother, for the music. i Acknowledgments A big thank you to every person who has joined and believed in me during my journey in the Catholic University of Portugal, in particular, the Professors Adriano Nazareth, Laura Castro, Rui Nunes, Alexandra Serapicos and Gonçalo de Vasconcelos e Sousa. I would also like to thank Professor Sahra Kunz for being my orienting teacher and guiding me during the entire process of writing this dissertation. I hope I match the expectations. Thank you to my colleagues, Manuel Guerra, Ana Paiva, Yoan Pimentel and Andrea “Blu” Medina, for their friendship and fun times together. A special thank you to my colleague Mara Ungureanu, for the endless nights spent in endless working sessions until dawn. Without you, it would have been much harder. Last but not least, I would like to thank the entire music video producing community. I hope we can keep growing, creating and innovating as much as we can. -

Tango Lessons

TANGO LESSONS TANGO LESSONS MOVEMENT, SOUND, IMAGE, AND TEXT IN CONTEMPORARY PRACTICE MARILYN G. MILLER, EDITOR Duke University Press • Durham and London • 2014 © 2014 Duke University Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper ∞ Typeset in Arno and Univers by Copperline Book Services, Inc. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Tango lessons : movement, sound, image, and text in contemporary practice / Marilyn G. Miller, ed. pages cm Includes bibliographical references and index. isbn 978-0-8223-5549-6 (cloth : alk. paper) isbn 978-0-8223-5566-3 (pbk. : alk. paper) 1. Tango (Dance)— Social aspects — History. 2. Tangos — History and criticism. i. Miller, Marilyn Grace, 1961– gv1796.t3t3369 2013 793.3'3 — dc23 2013025657 Duke University Press gratefully acknowledges the support of Tulane University, which provided funds toward the publication of this book. FOR EDUARDO CONTENTS ix Acknowledgments 1 INTRODUCTION • MARILYN G. MILLER 33 CHAPTER ONE • OSCAR CONDE Lunfardo in Tango: A Way of Speaking That Defines a Way of Being 60 CHAPTER TWO • ALEJANDRO SUSTI Borges, Tango, and Milonga 82 CHAPTER THREE • MARILYN G. MILLER Picturing Tango 118 CHAPTER FOUR • ANTONIO GÓMEZ Tango, Politics, and the Musical of Exile 140 CHAPTER FIVE • FERNANDO ROSENBERG The Return of the Tango in Documentary Film 164 CHAPTER SIX • CAROLYN MERRITT “Manejame como un auto”: Drive Me Like a Car, or What’s So New about Tango Nuevo? 198 CHAPTER SEVEN • MORGAN JAMES LUKER Contemporary Tango and the Cultural Politics of Música Popular 220 CHAPTER EIGHT • ESTEBAN BUCH Gotan Project’s Tango Project 243 Glossary 247 Works Cited 267 Contributors and Translators 269 Index ACKNOWLEDGMENTS A great many colleagues and fellow tangueros in Argentina, Uruguay, the United States, and elsewhere were extraordinarily gracious in sharing their time, knowledge, resources, and personal histories during the gestation of this edited volume. -

United Artists UAL-40000/UAL 4000 Mono/UAS 5000 Stereo Series

United Artists UAL-40000/UAL 4000 mono/UAS 5000 stereo Series UAL-40001 –Paris Holiday (Soundtrack) –Joe Lilley [1958] Overture/Paris Holiday –Bing Crosby and Bob Hope/Anita’sRumba/Theme for Ursula/The Last Time I Saw Paris –Bob Hope/Nothing in Common//Nothing in Common –Bing Crosby and Bob Hope/Taxis/Parisiens/April in Paris –Bob Hope/Carousel de Fernandel/Promenade des Champs Elysses/Finale UAL-40002 –God’sLittle Acre (Soundtrack) –Elmer Bernstein [1958] God’sLittle Acre/Diggin’in the Morning/The Prayer/Going to Town/The Love Scene/Will’sBlues/Chasing Darlin’Jill/Gold Hunt/The Fight/Poor Old Ty Ty/Griselda’stheme/Peachtree Valley Waltz/A Piano Solo/The Funerial/God’sLittle Acre UAL-40003 –The Vikings (Soundtrack) –Mario Nascimbene [1958] Violence and Rapes of the Vikings/Vikings Horn/Regnar Returns/Drunks Song-Eric is Rescued by Odins Daughter/Dancing the Oars/Eric and Morgana Escape- Love Scene/Aella Cuts Off Eric’sHand/Voage and Landing in Britain/The Vikings Attack the Castle-Battle and Death of Aellia/Duel-Eric Kills Einar/Funeral-End Titles UAL-40004 –The Big Country (Soundtrack) –Jerome Moross [1958] The Big Country/The Welcoming/Old Thunder/McKay's Triumph/The Waltz/The Old House//Big Muddy/The War Party Gathers/McKay In Blanco Canyon/The Death of Buck Hannesy/The Stalking/The Big Country Note: Numbering system changes here from 40000 to 4000. UAL-4003/UAS-5003 - The Vikings (Soundtrack) - Mario Nascimbene [1959] Reissue of UAL 40003 and released in stereo. UAL-4004/UAS-5004 –The Big Country (Soundtrack) –Jerome Moross [1959] Reissue of UAL 40004 and released in stereo.