The University of Chicago Scenes of Feeling: Music

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Volume 33, Number 04 (April 1915) James Francis Cooke

Gardner-Webb University Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 John R. Dover Memorial Library 4-1-1915 Volume 33, Number 04 (April 1915) James Francis Cooke Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude Part of the Composition Commons, Ethnomusicology Commons, Fine Arts Commons, History Commons, Liturgy and Worship Commons, Music Education Commons, Musicology Commons, Music Pedagogy Commons, Music Performance Commons, Music Practice Commons, and the Music Theory Commons Recommended Citation Cooke, James Francis. "Volume 33, Number 04 (April 1915)." , (1915). https://digitalcommons.gardner-webb.edu/etude/612 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the John R. Dover Memorial Library at Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. It has been accepted for inclusion in The tudeE Magazine: 1883-1957 by an authorized administrator of Digital Commons @ Gardner-Webb University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. < PRICE 15? #1-50 PER YEAR THE ETUDE 241 PLAN NOW FOR MUSICAL PROSPERITY A MONTHLY JOURNAL FOR THE MUSICIAN, THE MUSIC STUDENT, AND ALL MUSIC LOVERS. efaf' Edited by James Francis Cooke Subscription Price, $1.50 per year in United States, THIS SEASON AND NEXT Alaska, Cuba, Porto Rico, Mexico, Hawaii, Philippines, or Panama, Guam, Tutuila, and the City of Shanghai. In Canada, $1.75 per year. In England and Colonies, 9 Shill¬ ings; in France, 11 Francs; in Germany, 9 Marks. All other countries, $2.22 per year. inner Liberal premiums and cash deductions are allowed for Sophocles was right, “Fortune is never on the side of the fainthearted.” The resolute, fore-sighted Ainei lLcl SI IV1USC I caurci s And the last thing she uminem music worker wins. -

Riley Thorn and the Dead Guy Next Door

RILEY THORN AND THE DEAD GUY NEXT DOOR LUCY SCORE Copyright © 2020 Lucy Score All rights reserved No Part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electric or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without prior written permission from the publisher. The book is a work of fiction. The characters and events in this book are fictitious. Any similarity to real persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental and not intended by the author. ISBN: 978-1-945631-67-2 (ebook) ISBN: 978-1-945631-68-9 (paperback) lucyscore.com 082320 CONTENTS Chapter 1 Chapter 2 Chapter 3 Chapter 4 Chapter 5 Chapter 6 Chapter 7 Chapter 8 Chapter 9 Chapter 10 Chapter 11 Chapter 12 Chapter 13 Chapter 14 Chapter 15 Chapter 16 Chapter 17 Chapter 18 Chapter 19 Chapter 20 Chapter 21 Chapter 22 Chapter 23 Chapter 24 Chapter 25 Chapter 26 Chapter 27 Chapter 28 Chapter 29 Chapter 30 Chapter 31 Chapter 32 Chapter 33 Chapter 34 Chapter 35 Chapter 36 Chapter 37 Chapter 38 Chapter 39 Chapter 40 Chapter 41 Chapter 42 Chapter 43 Chapter 44 Chapter 45 Chapter 46 Chapter 47 Chapter 48 Chapter 49 Chapter 50 Chapter 51 Chapter 52 Chapter 53 Chapter 54 Chapter 55 Chapter 56 Chapter 57 Chapter 58 Chapter 59 Chapter 60 Epilogue Author’s Note to the Reader WONDERING WHAT TO READ NEXT?: About the Author Acknowledgments Lucy’s Titles To Josie, a real life badass. 1 10:02 p.m., Saturday, July 4 he dead talked to Riley Thorn in her dreams. -

Ukrainian Literature

UKRAINIAN LITERATURE A Journal of Translations Volume 5 2018 Shevchenko Scientific Society of Canada Ukrainian Literature A Journal of Translations Editor Maxim Tarnawsky Manuscript Editor Uliana M. Pasicznyk Editorial Board Taras Koznarsky, Askold Melnyczuk, Michael M. Naydan, Marko Pavlyshyn www.UkrainianLiterature.org Ukrainian Literature publishes translations into English of works of Ukrainian literature. The journal appears triennially on the internet at www.UkrainianLiterature.org and in a print edition. Ukrainian Literature is published by the Shevchenko Scientific Society of Canada, 516 The Kingsway, Toronto, ON M9A 3W6 Canada. The editors are deeply grateful to its Board of Directors for hosting the journal. Volume 5 (2018) of Ukrainian Literature was funded by a generous grant from the Danylo Husar Struk Programme in Ukrainian Literature of the Canadian Institute of Ukrainian Studies, University of Alberta, and by a substantial donation from Marta Tarnawsky. Ukrainian Literature depends on funding provided by sponsors. Donations can be sent to the Shevchenko Scientific Society of Canada. Please visit the journal website for more information about supporting the journal. Ukrainian Literature welcomes submissions. Please visit our website for the details of our call for submissions. Translators with potential submissions should contact the editor at [email protected]. ISSN 1552-5880 (online edition) ISSN 1552-5872 (print edition) Contents Introduction: Maxim Tarnawsky 5 YURI ANDRUKHOVYCH “Samiilo, or the Beautiful Brigand” Translated by Vitaly Chernetsky 9 VOLODYMYR DIBROVA “Savchuk” Translated by Lidia and Volodymyr Dibrova 17 MYKOLA KULISH The People’s Prophet Translated by George Mihaychuk 25 VALERIAN PIDMOHYLNY The City (Part 2) Translated by Maxim Tarnawsky 105 OLES ULIANENKO Stalinka (Part 1) Translated by Olha Rudakevych 235 MYKOLA RIABCHUK “Heron’s Birthday” Translated by Uliana M. -

Download Joe Thomas If U Lose Her

Download joe thomas if u lose her LINK TO DOWNLOAD Love renuzap.podarokideal.ru never disappoints me. TZ Comment by Shin Banga. quality. TZ Comment by Sueli Moura. Heaven this melody is heaven. TZ Comment by AV. This is real R&B & the lyrics greatness! TZ Comment by JAY love this song. TZ Buy If You Lose Her. Coming Back Home Love and Freedom · I Believe in You My Name Is Joe · All Or Nothing Everything · Lets Stay Home Tonight Better Days · If You Lose Her Bridges · All That I Am All That I Am · Peep Show My Name Is Joe · Priceless And Then · Worst Case Scenario Signature · Somebody Gotta Be. Jun 24, · If You Lose Her Lyrics: So you think there's a flicker in your flame / But your regiment of a loving her is still the same / Forgotten holidays, forsaken little things / It means so much to her. Joe, Joe Thomas – Ride Wit U (MTV Version) ft. G-Unit. Joe – Stutter (Remix Video Without Film Footage) Joe – Stutter. Joe – The Love Scene. Joe – Treat Her Like A Lady. Joe – If You Lose Her (feat. Kseniya Simonova) [Full Sand Story] Joe feat. Kseniya Simonova – If You Lose Her (Official Video). Download Joe mp3. Joe download high quality complete mp3 albums. Login: Joe Thomas New Man mp3 download Year: Artist: Joe Quality: High Rating: Joe - Joe Thomas New Man album Track listing: No. Title: I lose myself in a daydream where I stand and say Don’t say yes, run away now. Complete song listing of Joe on renuzap.podarokideal.ru COVID Because of processes designed to ensure the safety of our employees, you may experience a delay in the shipping of your order. -

Georg Wildhagen's Figaros Hochzeit How an Italian Opera Based on a French Play Became a German Socialist Film

Georg Wildhagen's Figaros Hochzeit How an Italian Opera Based on a French Play Became a German Socialist Film Thesis Presented in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts in the Graduate School of The Ohio State University By Alison M. Furlong, B.A. Graduate Program in Music The Ohio State University 2010 Thesis Committee: Lois Rosow, Advisor Danielle Fosler-Lussier Andrew Spencer Copyright by Alison M. Furlong 2010 Abstract On November 25, 1949, only seven weeks after the official establishment of the new German Democratic Republic (GDR), the German Film Studio DEFA (Deutsche Film Aktiengesellschaft) released Figaros Hochzeit, a new film adaptation of Mozart's Le nozze di Figaro, written and directed by novice filmmaker Georg Wildhagen. This is but one of many transpositions of the Figaro text, however, as Mozart and Da Ponte's Le nozze di Figaro was itself a transposition of Beaumarchais's play. Wildhagen’s setting must be viewed as a reinterpretation of the opera, transposed both for the medium of film and for the context of the new, and frighteningly unstable, Soviet Zone of occupation. Within this context, the aristocracy must be eliminated as a positive force; thus Count Almaviva is made more villainous and his wife Rosina is recast as a duplicitous schemer. Meanwhile, Figaro’s characterization is significantly altered, and only Susanna remains as a wholly virtuous individual. In Wildhagen’s hands, Figaros Hochzeit creates a new text, one that reflects the ideals and anxieties of the postwar Soviet Zone. ii Dedication For Calvin, to whom I owe a great many trips to the zoo iii Acknowledgements I wish to thank my advisor, Lois Rosow, for her incredible patience and encouragement as this thesis gradually developed from a feminist analysis of the eighteenth-century Rosina into a socio-political analysis of Wildhagen's mid twentieth- century film adaptation. -

Untitled, It Is Impossible to Know

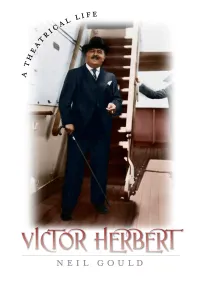

VICTOR HERBERT ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:09 PS PAGE i ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:09 PS PAGE ii VICTOR HERBERT A Theatrical Life C:>A<DJA9 C:>A<DJA9 ;DG9=6BJC>K:GH>INEG:HH New York ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE iii Copyright ᭧ 2008 Neil Gould All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means—electronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any other—except for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior permission of the publisher. Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gould, Neil, 1943– Victor Herbert : a theatrical life / Neil Gould.—1st ed. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN-13: 978-0-8232-2871-3 (cloth) 1. Herbert, Victor, 1859–1924. 2. Composers—United States—Biography. I. Title. ML410.H52G68 2008 780.92—dc22 [B] 2008003059 Printed in the United States of America First edition Quotation from H. L. Mencken reprinted by permission of the Enoch Pratt Free Library, Baltimore, Maryland, in accordance with the terms of Mr. Mencken’s bequest. Quotations from ‘‘Yesterthoughts,’’ the reminiscences of Frederick Stahlberg, by kind permission of the Trustees of Yale University. Quotations from Victor Herbert—Lee and J.J. Shubert correspondence, courtesy of Shubert Archive, N.Y. ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE iv ‘‘Crazy’’ John Baldwin, Teacher, Mentor, Friend Herbert P. Jacoby, Esq., Almus pater ................. 16820$ $$FM 04-14-08 14:34:10 PS PAGE v ................ -

MEIEA 2012 Color.Indd

Journal of the Music & Entertainment Industry Educators Association Volume 12, Number 1 (2012) Bruce Ronkin, Editor Northeastern University Published with Support from What’s Up with MXSups? Interviews with the Purveyors of Cool Andrea Johnson Berklee College of Music I’ve just finished watching my favorite nighttime dramaGrey’s Anat- omy1 and am again astounded by the amount of amazingly cool indepen- dent music placed in the show. Anyone’s Ghost by The National, Abducted by Cults, Chameleon/Comedian by Kathleen Edwards, Hit It by Miss Li, and Echoes by Mostar Diving Club.2 My husband and I are rabid fans of indie music and consider ourselves tastemakers in locating barely broken indie artists on sites such as www.gorillavsbear.net,3 www.newdust.com,4 www.stereogum.com,5 or www.indierockcafe.com,6 but I have to say I am continually blown away by the selections music supervisors make in to- day’s hit television shows. Week after week these women seem to have the uncanny knack for selecting überhip, underground artists barely breaking the film of the jel- lied mass of independent music consciousness. Women like Alexandra Patsavas of Chop Shop Music7 known for her work on Grey’s Anatomy,8 Andrea von Foerster of Firestarter Music9 known for her work on Modern Family,10 and Lindsay Wolfington of Lone Wolf,11 known for her work on One Tree Hill12 are not only outstanding entrepreneurs, they are purveyors of musical cool. How did they get to this coveted position—doling out delicious and delectable delights of divinely inspired discs? I was lucky enough to interview several of these women and delve into the minds of these modern day musical mavens. -

Edith Wharton's Treatment of Love: a Study of Conventionality and Unconventionality in Her Fiction

Louisiana State University LSU Digital Commons LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses Graduate School 1967 Edith Wharton's Treatment of Love: a Study of Conventionality and Unconventionality in Her Fiction. Jo Agnew Mcmanis Louisiana State University and Agricultural & Mechanical College Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses Recommended Citation Mcmanis, Jo Agnew, "Edith Wharton's Treatment of Love: a Study of Conventionality and Unconventionality in Her Fiction." (1967). LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses. 1351. https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_disstheses/1351 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at LSU Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in LSU Historical Dissertations and Theses by an authorized administrator of LSU Digital Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. This dissertation has been microfilmed exactly as received 67*17,334 McMANIS, Jo Agnew, 1941- EDITH WHARTON'S TREATMENT OF LOVE: A STUDY OF CONVENTIONALITY AND UNCONVENTIONALITY IN HER FICTION. Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College, Ph.D., 1967 Language and Literature, modern University Microfilms, Inc., Ann Arbor, Michigan EDITH WHARTON'S TREATMENT OP LOVE: A STUDY OF CONVENTIONALITY AND UNCONVENTIONALITY IN HER FICTION A Dissertation Submitted to the Graduate Faculty of the Louisiana State University and Agricultural and Mechanical College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in The Department of English by Jo Agnew McManis M.A., Louisiana State University, 1965 August, 1967 "Quotations from the following works by Edith Wharton are reprinted by special permission of Charles Scribner's Sons: THE HOUSE OF MIRTH, ETHAN FROME (Copyright 1911 Charles Scribner's Sons; renewal copyright 1939 Wm. -

9.1 GB # Artist Title Length 01 2Pac Do for Love 04:37

Total tracks number: 958 Total tracks length: 67:52:34 Total tracks size: 9.1 GB # Artist Title Length 01 2pac Do For Love 04:37 02 2pac Thug Mansion 03:32 03 2pac Thugz Mansion (Real) 04:06 04 2pac Wonder If Heaven Got A Ghetto 04:36 05 2pac Daz Kurupt Baby Dont Cry Remix 05:20 06 3lw No More 04:20 07 7 Mile Do Your Thing 04:49 08 8Ball & MJG You Don't Want Drama 04:32 09 112 Anywhere 04:04 10 112 Crazy over You 05:20 11 112 Cupid (Radio Mix) 04:08 12 112 Cupid 04:08 13 112 It's Over Now 04:00 14 112 Love You Like I Did 04:17 15 112 Only You (Slow Remix) 04:11 16 504 Boys Wobble Wobble Edited 03:42 17 504 Boys Wobble 03:38 18 702 Get It Together 04:50 19 702 Where My Girls At 02:45 20 1000 Clowns (Not The) Greatest Rapper 03:48 21 A Boogie Wit da Hoodie Drowning (feat. Kodak Black) 03:28 22 Aaliyah 4 Page Letter 04:50 23 Aaliyah Age Aint Nothing But A Number 03:37 24 Aaliyah Are You That Somebody 04:24 25 Aaliyah Dust Yourself Off 04:41 26 Aaliyah Hot Like Fire (Timbaland Remix 04:32 27 Aaliyah I Care 4 U 04:31 28 Aaliyah I Don't Wanna 04:12 29 Aaliyah If Your Girl Only Knew 04:50 30 Aaliyah More Than A Woman 03:48 31 Aaliyah One In A Million 04:29 32 Aaliyah Rock The Boat 04:33 33 Aaliyah The One I Gave My Heart To 03:52 34 Aaliyah Try Again 04:39 35 Aaliyah Ft. -

Tannhäuser: Poet and Legend COLLEGE of ARTS and SCIENCES Imunci Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures

Tannhäuser: Poet and Legend COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES ImUNCI Germanic and Slavic Languages and Literatures From 1949 to 2004, UNC Press and the UNC Department of Germanic & Slavic Languages and Literatures published the UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures series. Monographs, anthologies, and critical editions in the series covered an array of topics including medieval and modern literature, theater, linguistics, philology, onomastics, and the history of ideas. Through the generous support of the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Andrew W. Mellon Foundation, books in the series have been reissued in new paperback and open access digital editions. For a complete list of books visit www.uncpress.org. Tannhäuser: Poet and Legend With Texts and Translations of his Works j. w. thomas UNC Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures Number 77 Copyright © 1974 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons cc by-nc-nd license. To view a copy of the license, visit http://creativecommons. org/licenses. Suggested citation: Thomas, J. W.Tannhäuser: Poet and Legend: With Texts and Translations of his Works. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1974. doi: https://doi.org/10.5149/9781469658483_ Thomas Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Names: Thomas, John Wesley. Title: Tannhäuser : poet and legend / by John Wesley Thomas. Other titles: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures ; no. 77. Description: Chapel Hill : University of North Carolina Press, [1974] Series: University of North Carolina Studies in the Germanic Languages and Literatures. | Includes bibliographical references. Identifiers: lccn 73-15986 | isbn 978-1-4696-5847-6 (pbk: alk. -

Film Music and Film Genre

Film Music and Film Genre Mark Brownrigg A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy University of Stirling April 2003 FILM MUSIC AND FILM GENRE CONTENTS Page Abstract Acknowledgments 11 Chapter One: IntroductionIntroduction, Literature Review and Methodology 1 LiteratureFilm Review Music and Genre 3 MethodologyGenre and Film Music 15 10 Chapter Two: Film Music: Form and Function TheIntroduction Link with Romanticism 22 24 The Silent Film and Beyond 26 FilmTheConclusion Function Music of Film Form Music 3733 29 Chapter Three: IntroductionFilm Music and Film Genre 38 FilmProblems and of Genre Classification Theory 4341 FilmAltman Music and Genre and GenreTheory 4945 ConclusionOpening Titles and Generic Location 61 52 Chapter Four: IntroductionMusic and the Western 62 The Western and American Identity: the Influence of Aaron Copland 63 Folk Music, Religious Music and Popular Song 66 The SingingWest Cowboy, the Guitar and other Instruments 73 Evocative of the "Indian""Westering" Music 7977 CavalryNative and American Civil War WesternsMusic 84 86 PastoralDown andMexico Family Westerns Way 89 90 Chapter Four contd.: The Spaghetti Western 95 "Revisionist" Westerns 99 The "Post - Western" 103 "Modern-Day" Westerns 107 Impact on Films in other Genres 110 Conclusion 111 Chapter Five: Music and the Horror Film Introduction 112 Tonality/Atonality 115 An Assault on Pitch 118 Regular Use of Discord 119 Fragmentation 121 Chromaticism 122 The A voidance of Melody 123 Tessitura in extremis and Unorthodox Playing Techniques 124 Pedal Point -

JB DB by Artist

Song Title …. Artists Drop (Dirty) …. 216 Hey Hey …. 216 Baby Come On …. (+44) When Your Heart Stops Beating …. (+44) 96 Tears …. ? & The Mysterians Rubber Bullets …. 10cc The Things We Do For Love …. 10cc The Things We Do For Love …. 10cc Come See Me …. 112' Cupid …. 112' Damn …. 112' Dance With Me …. 112' God Knows …. 112' I'm Sorry (Interlude) …. 112' Intro …. 112' Just A Little While …. 112' Just A Little While …. 112' Last To Know …. 112' Let This Go …. 112' Let This Go …. 112' Love Me …. 112' My Mistakes …. 112' Nowhere …. 112' Only You …. 112' Peaches & Cream …. 112' Peaches & Cream (Clean) …. 112' Peaches & Cream (Dirty) …. 112' Peaches & Cream (Inst) …. 112' That's How Close We Are …. 112' U Already Know …. 112' U Already Know …. 112' We Goin' Be Alright …. 112' What If …. 112' What The H**l Do You Want …. 112' Why Can't We Get Along …. 112' You Already Know (Clean) …. 112' Dance Wit Me (Remix) …. 112' (w Beanie Segal) It's Over (Remix) …. 112' (w G.Dep & Prodigy) The Way …. 112' (w Jermaine Dupri) Hot & Wet (Dirty) …. 112' (w Ludacris) Love Me …. 112' (w Mase) Only You …. 112' (w Notorious B.I.G.) Anywhere (Remix) …. 112' (w Shyne) If I Can Hit …. 112' (w T.I.) If I Hit …. 112' (w T.I.) Closing The Club …. 112' (w Three 6 Mafia) Dunkie Butt …. 12 Gauge Lie To Me …. 12 Stones 1, 2, 3 Red Light …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Goody Goody Gumdrops …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Indian Giver …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simple Simon Says …. 1910 Fruitgum Co. Simple Simon Says ….