Access to Water Sharing Access on Rivers and Reservoirs

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Transits of the Northwest Passage to End of the 2019 Navigation Season Atlantic Ocean ↔ Arctic Ocean ↔ Pacific Ocean

TRANSITS OF THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE TO END OF THE 2019 NAVIGATION SEASON ATLANTIC OCEAN ↔ ARCTIC OCEAN ↔ PACIFIC OCEAN R. K. Headland and colleagues 12 December 2019 Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Lensfield Road, Cambridge, United Kingdom, CB2 1ER. <[email protected]> The earliest traverse of the Northwest Passage was completed in 1853 but used sledges over the sea ice of the central part of Parry Channel. Subsequently the following 314 complete maritime transits of the Northwest Passage have been made to the end of the 2019 navigation season, before winter began and the passage froze. These transits proceed to or from the Atlantic Ocean (Labrador Sea) in or out of the eastern approaches to the Canadian Arctic archipelago (Lancaster Sound or Foxe Basin) then the western approaches (McClure Strait or Amundsen Gulf), across the Beaufort Sea and Chukchi Sea of the Arctic Ocean, through the Bering Strait, from or to the Bering Sea of the Pacific Ocean. The Arctic Circle is crossed near the beginning and the end of all transits except those to or from the central or northern coast of west Greenland. The routes and directions are indicated. Details of submarine transits are not included because only two have been reported (1960 USS Sea Dragon, Capt. George Peabody Steele, westbound on route 1 and 1962 USS Skate, Capt. Joseph Lawrence Skoog, eastbound on route 1). Seven routes have been used for transits of the Northwest Passage with some minor variations (for example through Pond Inlet and Navy Board Inlet) and two composite courses in summers when ice was minimal (transits 149 and 167). -

The Chronicle Monday, February 15, 1988 « Duke University Durham, North Carolina Circulation: 15.000 Vol

THE CHRONICLE MONDAY, FEBRUARY 15, 1988 « DUKE UNIVERSITY DURHAM, NORTH CAROLINA CIRCULATION: 15.000 VOL. 83, NO. 100 Durham police chief selection nears ByCARLGHATTAS reported that he quit the post without spending any Durham city manager Orville Powell's announcement time on the job, saying that the Durham position was his at noon today of his plans for picking a new police chief first choice. should mark the beginning of the end of a controversy Another candidate, James Carvino, former chief of the surrounding the city's selection process. The process, U.S. Capitol Police, allegedly used department funds to which has narrowed the field of candidates down to produce a videotape tribute to his former secretary in three, has been marred by rumors of racial pressures Racine, Wis., according to The Herald. The General Ac and allegations of wrongdoings against two of the three. counting Office audited Carvino's department but could A background check on each of the candidates is the not find any evidence of criminal wrongdoing. last step before a final decision. y*"^k The selection process itself has been plagued by "You normally don't find ^^=B5(| )1 rumors of racial pressures which according to Powell anything," Powell said, because at rTf VX_>H, TR have originated from the media. The rumors suggest the beginning of the selection each that there has been pressure to select a black police candidate is asked if anything in chief. Powell denied these claims, calling the process so his past may prove to be embar OWN complex that such a move would be impossible. -

CIMM Library, by Title, 6/22/2020

CIMM Library, by Title, 6/22/2020 Author Title Dewey Keywords Gudde, 1000 California place names: their Erwin 979.4 GUD Names, Geographical -- California origin and meaning Gustav Howarth, Great Britain -- History -- Norman David 1066 : the year of the conquest 942.02 HOW period,, 1066-1154, Hastings, Battle Armine of, England, 1066 Wise, James May 1975 - Gulf of Thailand - The 14-hour war 972.956 WIS E. Vietnam War Discoveries in geography -- Chinese, Voyages around the world, MENZIES, 1421: THE YEAR CHINA 910.951 MEN China -- History -- Ming dynasty, GAVIN DISCOVERED THE WORLD 1368-1644, Ontdekkingsreizen, Wereldreizen MENZIES, 1434 945.05MEN GAVIN Galleons -- Juvenile literature, Humble, Seafaring life -- History -- 16th A 16th century galleon 623.822 HUM Richard century --, Juvenile literature, Galleons, Ships -- History Great Britain -- History, Naval -- 18th century, Santa Cruz de 1797 : Nelson's year of destiny : Cape Tenerife, Battle of, Santa Cruz de, White, St. Vincent and Santa Cruz de 940.27 WHI Tenerife, Canary Islands, 1797, Colin Tenerife Cape Saint Vincent, Battle of, 1797, Nelson, Horatio Nelson, Viscount, 1758-1805 --, Military leadership 20,000 leagues under the sea. Submarines (Ships) --Fiction, Sea Verne, Jules [Fic] VER Illustrated by Don Irwin stories, Science fiction 20,000 leagues under the sea. Submarines (Ships) --Fiction, Sea Verne, Jules [Fic] VER Illustrated by Don Irwin stories, Science fiction 20,000 leagues under the sea. Submarines (Ships) --Fiction, Sea Verne, Jules [Fic] VER Illustrated by Don Irwin stories, Science fiction Goodwin, The 20-gun ship Blandford 623.8 BLA gunship, Blandford Peter Adams, Jack 21 California Missions 979.4 ADA Missions, California, Paintings L. -

The Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition 1955-1958

THE COMMONWEALTH TRANS-ANTARCTIC EXPEDITION 1955-1958 HOW THE CROSSING OF ANTARCTICA MOVED NEW ZEALAND TO RECOGNISE ITS ANTARCTIC HERITAGE AND TAKE AN EQUAL PLACE AMONG ANTARCTIC NATIONS A thesis submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for the Degree PhD - Doctor of Philosophy (Antarctic Studies – History) University of Canterbury Gateway Antarctica Stephen Walter Hicks 2015 Statement of Authority & Originality I certify that the work in this thesis has not been previously submitted for a degree nor has it been submitted as part of requirements for a degree except as fully acknowledged within the text. I also certify that the thesis has been written by me. Any help that I have received in my research and the preparation of the thesis itself has been acknowledged. In addition, I certify that all information sources and literature used are indicated in the thesis. Elements of material covered in Chapter 4 and 5 have been published in: Electronic version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume00,(0), pp.1-12, (2011), Cambridge University Press, 2011. Print version: Stephen Hicks, Bryan Storey, Philippa Mein-Smith, ‘Against All Odds: the birth of the Commonwealth Trans-Antarctic Expedition, 1955-1958’, Polar Record, Volume 49, Issue 1, pp. 50-61, Cambridge University Press, 2013 Signature of Candidate ________________________________ Table of Contents Foreword .................................................................................................................................. -

Arctic Marine Transport Workshop 28-30 September 2004

Arctic Marine Transport Workshop 28-30 September 2004 Institute of the North • U.S. Arctic Research Commission • International Arctic Science Committee Arctic Ocean Marine Routes This map is a general portrayal of the major Arctic marine routes shown from the perspective of Bering Strait looking northward. The official Northern Sea Route encompasses all routes across the Russian Arctic coastal seas from Kara Gate (at the southern tip of Novaya Zemlya) to Bering Strait. The Northwest Passage is the name given to the marine routes between the Atlantic and Pacific oceans along the northern coast of North America that span the straits and sounds of the Canadian Arctic Archipelago. Three historic polar voyages in the Central Arctic Ocean are indicated: the first surface shop voyage to the North Pole by the Soviet nuclear icebreaker Arktika in August 1977; the tourist voyage of the Soviet nuclear icebreaker Sovetsky Soyuz across the Arctic Ocean in August 1991; and, the historic scientific (Arctic) transect by the polar icebreakers Polar Sea (U.S.) and Louis S. St-Laurent (Canada) during July and August 1994. Shown is the ice edge for 16 September 2004 (near the minimum extent of Arctic sea ice for 2004) as determined by satellite passive microwave sensors. Noted are ice-free coastal seas along the entire Russian Arctic and a large, ice-free area that extends 300 nautical miles north of the Alaskan coast. The ice edge is also shown to have retreated to a position north of Svalbard. The front cover shows the summer minimum extent of Arctic sea ice on 16 September 2002. -

99-00 May No. 4

THE ANTARCTICAN SOCIETY 7338 Wayfarer Drive Fairfax Station, Virginia 22039 HONORARY PRESIDENT — MRS. PAUL A. SIPLE Vol. 99-00 May No. 4 Presidents: Dr. Carl R. Eklund, 1959-61 Dr. Paul A. Siple, 1961-62 Mr. Gordon D. Cartwright, 1962-63 BRASH ICE RADM David M. Tyree (Ret.), 1963-64 Mr. George R. Toney, 1964-65 Mr. Morton J. Rubin, 1965-66 Dr. Albert R Crary, 1966-68 As you can readily see, this newsletter is NOT announcing a speaker Dr. Henry M. Dater, 1968-70 program, as we have not lined anyone up, nor have any of you stepped Mr. George A. Doumani, 1970-71 Dr. William J. L. Sladen, 1971-73 forward announcing your availability. So we are just moving out with a Mr. Peter F. Bermel, 1973-75 Dr. Kenneth J. Bertrand, 1975-77 newsletter based on some facts, some fiction, some fabrications. It will be Mrs. Paul A. Siple, 1977-78 Dr. Paul C. Dalrymple, 1978-80 up to you to ascertain which ones are which. Good luck! Dr. Meredith F. Burrill, 1980-82 Dr. Mort D. Turner, 1982-84 Dr. Edward P. Todd, 1984-86 Two more Byrd men have been struck down -- Al Lindsey, the last of the Mr. Robert H. T. Dodson, 1986-88 Dr. Robert H. Rutford, 1988-90 Byrd scientists to die, and Steve Corey, Supply Officer, both of the 1933-35 Mr. Guy G. Guthridge, 1990-92 Byrd Antarctic Expedition. Al was a handsome man, and he and his wife, Dr. Polly A. Penhale, 1992-94 Mr. Tony K. Meunier, 1994-96 Elizabeth, were a stunning couple. -

Saturday 12 October 2013

EDITOR’S LETTER THE MAGAZINE FOR OLD STOICS Issue 3 FEATURES 8 NINETY YEARS OF STOWE 33 POLAR BOUND A brisk canter through ninety Having recently completed his fifth glorious years of achievements, transit of the North West Passage, Welcome to the 90th memories and special occasions. David Scott Cowper reports on his Arctic adventures. anniversary edition of 14 HOLLYWOOD COMPOSOR The Corinthian – the IN RESIDENCE 38 OLD STOIC BANDS Old Stoic, Harry Gregson-Williams, Nigel Milne discovers the influence magazine for Old Stoics. swaps his studio in Los Angeles for of Rock ’n’ Roll on Stoics through a year in the Queen’s Temple. the generations. This magazine chronicles the 16 AN AFTERNOON WITH 41 CELEBRATE ALL THINGS VISUAL Society’s activities over the last SIR NICHOLAS Winton An insight into the myriad of year and includes news from Two current Stoics meet Sir talented artists who started out Old Stoics across the globe. Nicholas Winton to learn about at Stowe. In celebration of the 90th his years at Stowe and remarkable anniversary, this edition includes achievements thereafter. features inspired by Stowe’s history through the years. REGULARS I hope you enjoy reading it. 1 EDITORIAL 29 BIRTHS Thank you to everyone who has sent in their news, and to all 4 FROM THE HEADMASTER 30 OBITUARIES those who have written articles. 18 NEWS 56 STOWE’S RICH HISTORY Thank you, also, for the time you have given to make this magazine 28 MARRIAGES burst at the seams, to the OS advertisers who have supported INSIDE the magazine, and to Caroline Whitlock, for spending countless 2 THE NEW OSS CHAIRMAN 55 COLLECTING ABROAD FOR THE V&A hours collating your news. -

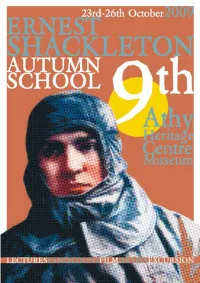

Sir Ernest Shackleton

Sir Ernest Shackleton Born close to the village of Kilkea, FRIDAY 23rd October between Castledermot and Athy, in the south of County Kildare in 1874, Ernest Shackleton Official Opening & is renowned for his courage, his commitment to the welfare of his comrades and his Book Launch immense contribution to exploration and 7.30pm in Athy Heritage Centre - geographical discovery. The Shackleton family Museum first came to south Kildare in the early years of the eighteenth century. Ernest’s Quaker In association with the Erskine Press the forefather, Abraham Shackleton, established a multi-denominational school in the village school will host the launch of Regina Daly’s of Ballitore. This school was to educate such book notable figures as Napper Tandy, Edmund ‘The Shackleton Letters: Behind the Scenes of Burke, Cardinal Paul Cullen and Shackleton’s the Nimrod Expedition’. great aunt, the Quaker writer, Mary Leadbeater. Apart from their involvement in education, the extended family was also deeply involved in Shackleton the business and farming life of south Kildare. Having gone to sea as a teenager, Memorial Lecture Shackleton joined Captain Scott’s Discovery expedition (1901 – 1904) and, in time, was by Caroline Casey to lead three of his own expeditions to the Antarctic. His Endurance expedition (1914 – 8.15pm in Athy Heritage Centre - Museum 1916) has become known as one of the great epics of human survival. He died in 1922, at The founder and CEO of Kanchi (formerly South Georgia, on his fourth expedition to the known as The Aisling Foundation) Caroline is Antarctic, and – on his wife’s instructions – was buried there. -

Transits of the Northwest Passage to End of the 2020 Navigation Season Atlantic Ocean ↔ Arctic Ocean ↔ Pacific Ocean

TRANSITS OF THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE TO END OF THE 2020 NAVIGATION SEASON ATLANTIC OCEAN ↔ ARCTIC OCEAN ↔ PACIFIC OCEAN R. K. Headland and colleagues 7 April 2021 Scott Polar Research Institute, University of Cambridge, Lensfield Road, Cambridge, United Kingdom, CB2 1ER. <[email protected]> The earliest traverse of the Northwest Passage was completed in 1853 starting in the Pacific Ocean to reach the Atlantic Oceam, but used sledges over the sea ice of the central part of Parry Channel. Subsequently the following 319 complete maritime transits of the Northwest Passage have been made to the end of the 2020 navigation season, before winter began and the passage froze. These transits proceed to or from the Atlantic Ocean (Labrador Sea) in or out of the eastern approaches to the Canadian Arctic archipelago (Lancaster Sound or Foxe Basin) then the western approaches (McClure Strait or Amundsen Gulf), across the Beaufort Sea and Chukchi Sea of the Arctic Ocean, through the Bering Strait, from or to the Bering Sea of the Pacific Ocean. The Arctic Circle is crossed near the beginning and the end of all transits except those to or from the central or northern coast of west Greenland. The routes and directions are indicated. Details of submarine transits are not included because only two have been reported (1960 USS Sea Dragon, Capt. George Peabody Steele, westbound on route 1 and 1962 USS Skate, Capt. Joseph Lawrence Skoog, eastbound on route 1). Seven routes have been used for transits of the Northwest Passage with some minor variations (for example through Pond Inlet and Navy Board Inlet) and two composite courses in summers when ice was minimal (marked ‘cp’). -

Inventory Acc.12696 William Laird Mckinlay

Acc.12696 December 2006 Inventory Acc.12696 William Laird McKinlay National Library of Scotland Manuscripts Division George IV Bridge Edinburgh EH1 1EW Tel: 0131-466 2812 Fax: 0131-466 2811 E-mail: [email protected] © Trustees of the National Library of Scotland Correspondence and papers of William Laird McKinlay, Glasgow. Background William McKinlay (1888-1983) was for most of his working life a teacher and headmaster in the west of Scotland; however the bulk of the papers in this collection relate to the Canadian National Arctic Expedition, 1913-18, and the part played in it by him and the expedition leader, Vilhjalmur Stefansson. McKinlay’s account of his experiences, especially those of being shipwrecked and marooned on Wrangel Island, off the coast of Siberia, were published by him in Karluk (London, 1976). For a rather more detailed list of nos.1-27, and nos.43-67 (listed as nos.28-52), see NRA(S) survey no.2546. Further items relating to McKinlay were presented in 2006: see Acc.12713. Other items, including a manuscript account of the expedition and the later activities of Stefansson – much broader in scope than Karluk – have been deposited in the National Archives of Canada, in Ottawa. A small quantity of additional documents relating to these matters can be found in NRA(S) survey no.2222, papers in the possession of Dr P D Anderson. Extent: 1.56 metres Deposited in 1983 by Mrs A.A. Baillie-Scott, the daughter of William McKinlay, and placed as Dep.357; presented by the executor of Mrs Baillie-Scott’s estate, November 2006. -

The Power in Lilian Ngoyi and Fannie Lou Hamer

Georgia State University ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University History Theses Department of History 8-10-2009 Relays in Rebellion: The Power in Lilian Ngoyi and Fannie Lou Hamer Cathy LaVerne Freeman Georgia State University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses Part of the History Commons Recommended Citation Freeman, Cathy LaVerne, "Relays in Rebellion: The Power in Lilian Ngoyi and Fannie Lou Hamer." Thesis, Georgia State University, 2009. https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/history_theses/39 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of History at ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. It has been accepted for inclusion in History Theses by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University. For more information, please contact [email protected]. RELAYS IN REBELLION: THE POWER IN LILIAN NGOYI AND FANNIE LOU HAMER by CATHY L. FREEMAN Under the Direction of Michelle Brattain ABSTRACT This thesis compares how Lilian Ngoyi of South Africa and Fannie Lou Hamer of the United States crafted political identities and assumed powerful leadership, respectively, in struggles against racial oppression via the African National Congress and the Student Non-Violent Coordinating Committee. The study asserts that Ngoyi and Hamer used alternative sources of personal power which arose from their location in the intersecting social categories of culture, gender and class. These categories challenge traditional disciplinary boundaries and complicate any analysis of political economy, state power relations and black liberation studies which minimize the contributions of women. Also, by analyzing resistance leadership squarely within both African and North American contexts, this thesis answers the call of scholar Patrick Manning for a “homeland and diaspora” model which positions Africa itself within the historiography of transnational academic debates. -

Paine, Ships of the World Bibliography

Bibliography The bibliography includes publication data for every work cited in the source notes of the articles. It should be noted that while there are more than a thousand titles listed, this bibliography can by no means be considered exhaustive. Taken together, the literature on the Titanic, Bounty, and Columbus’s Niña, Pinta, and Santa María comprises hundreds of books and articles. Even a comprehensive listing of nautical bibliographies is impossible here, though four have been especially helpful in researching this book: Bridges, R.C., and P. E. H. Hair. Compassing the Vaste Globe of the Earth: Studies in the History of the Hakluyt Society 1846–1896. London: Hakluyt Society, 1996. Includes a list of the more than 300 titles that have appeared under the society’s imprint. Labaree, Benjamin W. A Supplement (1971–1986) to Robert G. Albion’s Naval & Maritime History: An Annotated Bibliography. 4th edition. Mystic, Conn.: Mystic Seaport Museum, 1988. Law, Derek G. The Royal Navy in World War Two: An Annotated bibliography. London: Greenhill Books, 1988. National Maritime Museum (Greenwich, England). Catalogue of the Library, Vol. 1, Voyages and Travel. London: Her Majesty’s Stationery Office, 1968. There are many interesting avenues of research in maritime history on the Internet. Two have been particularly useful: Maritime History Virtual Archives, owned and administered by Lar Bruzelius. URL: http://pc-78– 120.udac.se:8001/WWW/Nautica/Nautica.html Rail, Sea and Air InfoPages and FAQ Archive (Military and TC FAQs), owned and administered by Andrew Toppan. URL: http://www.membrane.com/~elmer/ mirror: http://www.announce.com/~elmer/.