Campephilus Pollens) (No

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

OCTOBER–DECEMBER 2011 Vermilion Flycatcher

THE QUARTERLY NEWS MAGAZINE OF TUCSON AUDUBON SOCIETY | TUCSONAUDUBON.ORG VermFLYCATCHERilion October–December 2011 | Volume 56, Number 4 Evolving Birds of Prey in Urban Tucson Lawns, Landscaping, and Native Birds Avra Valley Wastewater Ponds Still Produce the Birds What’s in a Name? Lesser Nighthawk PLUS special four-page holiday gift ideas pull-out Features THE QUARTERLY NEWS MAGAZINE OF TUCSON AUDUBON SOCIETY | TUCSONAUDUBON.ORG 13 What’s in a Name? Lesser Nighthawk VermilionFLYCATCHER 14 Birds of Prey in Urban Tucson October–December 2011 | Volume 56, Number 4 16 Lawns, Landscaping, and Native Tucson Audubon Society is dedicated to improving Birds the quality of the environment by providing education, conservation, and recreation programs, environmental 18 Avra Valley Wastewater Ponds Still leadership, and information. Tucson Audubon is a Produce the Birds non-profit volunteer organization of people with a common interest in birding and natural history. Tucson Audubon maintains offices, a library, and nature Departments Evolving shops in Tucson, the proceeds of which benefit all of Birds of Prey in 3 Commentary Urban Tucson its programs. Lawns, Landscaping, and Native Birds Tucson Audubon Society 4 Events and Classes 300 E. University Blvd. #120, Tucson, AZ 85705 5 Events Calendar 629-0510 (voice) or 623-3476 (fax) Avra Valley Wastewater Ponds All phone numbers are area code 520 unless otherwise stated. Still Produce the Birds 8 News Roundup What’s in a Name? Lesser Nighthawk www.tucsonaudubon.org PLUS special four-page holiday gift ideas pull-out Board Officers & Directors 19 Conservation and Education News President Cynthia Pruett Vice President Sandy Elers 22 Field Trips FRONT COVER: Buff-breasted Flycatcher photographed Secretary Ruth Russell in Carr Canyon by Robert Royse. -

On Birds of Santander-Bio Expeditions, Quantifying The

Facultad de Ciencias ACTA BIOLÓGICA COLOMBIANA Departamento de Biología http://www.revistas.unal.edu.co/index.php/actabiol Sede Bogotá ARTÍCULO DE INVESTIGACIÓN / RESEARCH ARTICLE ZOOLOGÍA ON BIRDS OF SANTANDER-BIO EXPEDITIONS, QUANTIFYING THE COST OF COLLECTING VOUCHER SPECIMENS IN COLOMBIA Sobre las aves de las expediciones Santander-Bio, cuantificando el costo de colectar especímenes en Colombia Enrique ARBELÁEZ-CORTÉS1 *, Daniela VILLAMIZAR-ESCALANTE1 , Fernando RONDÓN-GONZÁLEZ2 1Grupo de Estudios en Biodiversidad, Escuela de Biología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Carrera 27 Calle 9, Bucaramanga, Santander, Colombia. 2Grupo de Investigación en Microbiología y Genética, Escuela de Biología, Universidad Industrial de Santander, Carrera 27 Calle 9, Bucaramanga, Santander, Colombia. *For correspondence: [email protected] Received: 23th January 2019, Returned for revision: 26th March 2019, Accepted: 06th May 2019. Associate Editor: Diego Santiago-Alarcón. Citation/Citar este artículo como: Arbeláez-Cortés E, Villamizar-Escalante D, and Rondón-González F. On birds of Santander-Bio Expeditions, quantifying the cost of collecting voucher specimens in Colombia. Acta biol. Colomb. 2020;25(1):37-60. DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.15446/abc. v25n1.77442 ABSTRACT Several scientific reasons support continuing bird collection in Colombia, a megadiverse country with modest science financing. Despite the recognized value of biological collections for the rigorous study of biodiversity, there is scarce information on the monetary costs of specimens. We present results for three expeditions conducted in Santander (municipalities of Cimitarra, El Carmen de Chucurí, and Santa Barbara), Colombia, during 2018 to collect bird voucher specimens, quantifying the costs of obtaining such material. After a sampling effort of 1290 mist net hours and occasional collection using an airgun, we collected 300 bird voucher specimens, representing 117 species from 30 families. -

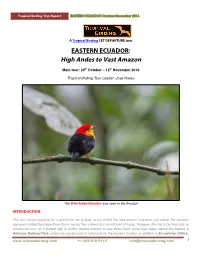

High Andes to Vast Amazon

Tropical Birding Trip Report EASTERN ECUADOR October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN ECUADOR: High Andes to Vast Amazon Main tour: 29th October – 12th November 2016 Tropical Birding Tour Leader: Jose Illanes This Wire-tailed Manakin was seen in the Amazon INTRODUCTION: This was always going to be a special for me to lead, as we visited the area where I was born and raised, the Amazon, and even visited the lodge there that is run by the community I am still part of today. However, this trip is far from only an Amazonian tour, as it started high in Andes (before making its way down there some days later), above the treeline at Antisana National Park, where we saw Ecuador’s national bird, the Andean Condor, in addition to Ecuadorian Hillstar, 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report EASTERN ECUADOR October-November 2016 Carunculated Caracara, Black-faced Ibis, Silvery Grebe, and Giant Hummingbird. Staying high up in the paramo grasslands that dominate above the treeline, we visited the Papallacta area, which led us to different high elevation species, like Giant Conebill, Tawny Antpitta, Many-striped Canastero, Blue-mantled Thornbill, Viridian Metaltail, Scarlet-bellied Mountain-Tanager, and Andean Tit-Spinetail. Our lodging area, Guango, was also productive, with White-capped Dipper, Torrent Duck, Buff-breasted Mountain Tanager, Slaty Brushfinch, Chestnut-crowned Antpitta, as well as hummingbirds like, Long-tailed Sylph, Tourmaline Sunangel, Glowing Puffleg, and the odd- looking Sword-billed Hummingbird. Having covered these high elevation, temperate sites, we then drove to another lodge (San Isidro) downslope in subtropical forest lower down. -

Colombia Remote 30Th Nov - 18Th Dec 2016 (19 Days) Trip Report

Colombia Remote 30th Nov - 18th Dec 2016 (19 days) Trip Report Emerald Tanager by Adam Riley Trip Report compiled by tour leader, Forrest Rowland Tour Participants: Stephen Bailey, Richard Greenhalgh, Leslie Kehoe, Glenn Sibbald, Jacob and Susan Van Sittert, Albert Williams Trip Report – RBL Colombia - Remote 2016 2 ___________________________________________________________________________________ Tour Summary Our newest tour to Colombia, the Remote birding tour, took us into many seldom-explored areas in search of an array of rare, special and localised species. Targets were many. Misses were few. Our exploits, to mention but a few, included such gems as Baudo Guan, Fuertes’s and Rose-faced Parrots, Flame-winged Parakeet, Dusky Starfrontlet, Baudo Oropendola, Urrao Antpitta, the recently described Perija Tapaculo, fascinating Recurve-billed Bushbird, jaw-dropping Multicolored Tanager, Yellow- green Bush Tanager (Chlorospingus), Colombian Chachalaca, Lined Quail-Dove, Esmeraldas and Magdalena Antbirds, Perija Metaltail, Perija Thistletail and Perija Brush Finch. An important aspect of this tour, which reached beyond just the wonderful multitude of species seen, was the adventure. Due to the nature of the sites visited, and their locations, we were truly immersed in a myriad of cultures, landscapes, and habitats indigenous to the Colombian countryside. Dusky Starfrontlet by Dubi Shapiro The tour convened in Bogota, the bustling capital city of Colombia. After meeting up for dinner and getting to know one another a bit, we went over the game plan. Our first order of business would be to descend the eastern cordillera of the Andes, in search of one of the most range-restricted, and difficult-to-see species – Cundinamarca Antpitta. -

The Andes & Amazon

Ecuador - The Andes & Amazon Naturetrek Tour Report 10 - 24 February 2018 San Isidro Black-Banded Owl Plate-Billed Mountain-Toucan Report kindly compiled by Kim Fleming Images courtesy of Howard Nelson Naturetrek Mingledown Barn Wolf's Lane Chawton Alton Hampshire GU34 3HJ UK T: +44 (0)1962 733051 E: [email protected] W: www.naturetrek.co.uk Tour Report Ecuador - The Andes & Amazon Tour participants: Manuel Sanchez (leader, except at Sacha Lodge), Edison Cisneros (driver) With three Naturetrek clients. Day 1 Saturday 10th February Having arrived on the morning before the official start of the trip, our small party was collected by Edison and delivered at our comfortable hotel in Quito. After a short rest we decided to walk to the nearby La Carolina Park and Botanical Gardens to try to spot one or two bird species on our own. Though the park was thronged with people enjoying an extended public holiday weekend, we did manage to identify some birds – the Vermilion Flycatchers were easy, as were the common Great Thrushes, and we were pleased to see our first Black Flowerpiercers. As well as plenty of Sparkling Violetears, in the Botanical Garden we had prolonged views of a Black-tailed Trainbearer. Day 2 Sunday 11th February Manuel and Edison arrived early the next morning to take us north-west out of the city to the Yanacocha Reserve. Here at around between 3,500m (11,500ft) and 3,700m (12,100ft) we were in the clouds. Careful not to overdo it at the unfamiliar altitude, we slowly walked the main Inca Trail, starting to encounter the sudden multi- species flocks so typical of neotropical birdwatching. -

Development, Armed Conflict and Conservation: Improving the Effectiveness of Conservation Decisions in Conflict Hotspots Using Colombia As a Case Study

Development, armed conflict and conservation: improving the effectiveness of conservation decisions in conflict hotspots using Colombia as a case study Pablo Jose Negret Master in Biological Science, Los Andes University A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2019 School of Earth and Environmental Sciences Abstract Pressure on Earth’s biodiversity is increasing worldwide, with at least one million species threatened with extinction and a 67% decline in vertebrate species populations over the last half century. Practical conservation actions that are able to generate the greatest conservation benefit in the most efficient way are needed. Colombia, a mega-diverse country, has the potential to preserve a considerable portion of the world’s biodiversity, making conservation in the country both regionally and globally relevant. However, human activities are transforming the country’s natural landscapes at an extremely high rate, making urgent the generation of effective conservation actions. Colombia, after decades of civil unrest, is now entering a post-conflict era. But the peace agreement signed in 2016 between the Colombian government and the strongest illegal armed group, FARC-EP is impacting the country’s biodiversity. New pressures are being imposed on areas of high biodiversity that previously were off-limits for development because of the conflict. This makes the generation of conservation plans particularly urgent. Post-conflict planning initiatives have the potential to limit environmental damage and increase formal protection of the most irreplaceable natural areas of Colombia. These plans need to be informed by an understanding of changes in risks to areas of high biodiversity importance, and the effectiveness of conservation efforts such as protected areas. -

Ecuador: Rainforest & Andes (Private) 2018

Field Guides Tour Report Ecuador: Rainforest & Andes (Private) 2018 Oct 2, 2018 to Oct 14, 2018 Mitch Lysinger For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. We saw some amazing hummingbirds on this tour, including the endemic Ecuadorian Hillstar. These gorgeous birds were seen up at Antisana. Photo by participant Wally Levernier. What a monster trip, with tons of birds - some rare, and many gorgeous! - stunning scenery all the way down the Andes and into the Amazon, and even some fascinating mammal species, including the rare and endangered Spectacled Bear. Our trip concentrated on the riches of the east slope, from the high windswept paramos that crest the Andes, through the lush temperate, subtropical, and foothill forests that blanket the slopes, and finally ending up down in the mega-diverse Amazonian lowlands along the mighty Napo River that, believe it or not, lie only about 800 feet above sea level... what a ride all the way! Denis, you put yet another wonderful adventure together for all of us. Everybody will certainly have their personal favorite birds of the trip, but here are some of the leader's picks for the birds that really sent the trip over the top, whether from an aesthetic standpoint, for rarity, or just for excitement: how about that scoped and singing Wattled Guan that we had from the porch at San Isidro (?); those range-restricted Black-faced Ibis feeding out on the plains at Antisana; those spectacular Andean Condors soaring at close range; a scoped female -

Ecuador's Wildsumaco Lodge 2015 BIRDS

Field Guides Tour Report Ecuador's Wildsumaco Lodge 2015 Mar 19, 2015 to Mar 29, 2015 Willy Perez For our tour description, itinerary, past triplists, dates, fees, and more, please VISIT OUR TOUR PAGE. This trip has a fantastic combination of birds to look for, some of them scarce or rare, and many unique in their habitat. Staying in just two lodges in the foothills of the eastern Ecuadorian Andes gives us a lot of time to seek them out. Our first morning at Antisana was exciting, with Carunculated Caracaras, Andean Lapwings, Andean Gulls, and Black- winged Ground-Doves everywhere. Andean Condors were sitting on their cliff early, but later on in the morning took to the air for glorious profiles. And to our great relief, on our way back from Antisana we saw 5 Black- faced Ibises walking through the grassland - hurray! The winner of that first morning, however, was definitely the Ecuadorian Hillstar male that perched to show its purple head and white chest so well. Our Guango stop next was a great opportunity to add 8 species of hummingbirds in 5 minutes and to enjoy a nice cup of coffee. After our arrival at San Isidro, the gardens were as good as ever. Crimson- mantled and Powerful woodpeckers were present, and we had good looks of the San Isidro Owl that continues at the site as well as many Black Agoutis. For some species we had to work hard, for example finding the Western Puffbird along the Loreto road, or the hike that we did to witness the magnificent nest of the Fiery-throated Fruiteater. -

Using Bird Distributions to Assess Extinction Risk and Identify Conservation Priorities In

Using Bird Distributions to Assess Extinction Risk and Identify Conservation Priorities in Biodiversity Hotspots by Natalia Ocampo-Peñuela Nicholas School of the Environment Duke University Date: _________________ Approved: ___________________________ Stuart L. Pimm, Supervisor ___________________________ Jennifer Swenson ___________________________ Nicholas Haddad ___________________________ John R. Poulsen Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 ABSTRACT Using Bird Distributions to Assess Extinction Risk and Identify Conservation Priorities in Biodiversity Hotspots by Natalia Ocampo-Peñuela Nicholas School of the Environment Duke University Date: _______________ Approved: 1 ___________________________ Stuart L. Pimm, Supervisor ___________________________ Jennifer Swenson ___________________________ Nicholas Haddad ___________________________ John Poulsen An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Graduate School of Duke University 2016 2 Copyright by Natalia Ocampo-Peñuela 2016 Abstract Habitat loss, fragmentation, and degradation threaten the World’s ecosystems and species. These, and other threats, will likely be exacerbated by climate change. Due to a limited budget for conservation, we are forced to prioritize a few areas over others. These places are selected based on their uniqueness and vulnerability. One of the most famous examples is the biodiversity hotspots: areas where large quantities of endemic species meet alarming rates of habitat loss. Most of these places are in the tropics, where species have smaller ranges, diversity is higher, and ecosystems are most threatened. Species distributions are useful to understand ecological theory and evaluate iv extinction risk. Small-ranged species, or those endemic to one place, are more vulnerable to extinction than widely distributed species. -

Ecuador: the Andes Introtour - January 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Ecuador: The Andes Introtour - January 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour Ecuador: The Andes Introtour with High Andes extension January 15-24, 2016 TOUR LEADER: ANDRÉS VÁSQUEZ Trip report and most photos by Andrés Vásquez Masked Mountain-Tanager, a rarity we saw on the extension The Andes Introtour is a wonderful tour to start exploring South America; it is moderately paced and somewhat relaxed thanks to the fact that we use a great lodge and only one during the entire main tour (the famed Tandayapa Bird Lodge) which means unpacking only once and not going through the stress of hopping from lodge to lodge. On the other hand, it is every bit as serious in terms of finding species as any other tour with some early starts and some late endings. It www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-0514 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Ecuador: The Andes Introtour - January 2016 does not sacrifice any bird opportunity, and proof of that is the incredible list we compiled during this tour and the awesome amount of rarities we managed to find thanks to the focus and great spirit of all the participants. This tour was particularly above average birding wise and INCREDIBLE for mammals; in one day of the extension we got 7 Andean Condors, 2 cooperative Rufous-belied Seedsnipes, Andean Ibis, a Black-breasted Buzzard-Eagle (among 5 species of raptors that day) plus 2 species of deer, the local subspecies of White-tailed Deer and the rare and secretive NORTHERN PUDU, just after finding a SPECTACLED BEAR (photo below by Steve Klesius) crossing the road in front of us. -

The Avifauna of Cajas National Park and Mazán Reserve, Southern Ecuador, with Notes on New Records Pedro X

Cotinga 37 The avifauna of Cajas National Park and Mazán Reserve, southern Ecuador, with notes on new records Pedro X. Astudillo, Boris A. Tinoco and David C. Siddons Received 1 June 2013; final revision accepted 23 February 2014 Cotinga 37 (2015): OL 1–11 published online 10 March 2015 El Parque Nacional Cajas es un área de interés para científicos y aficionados de las aves debido principalmente a su muestra representativa de los ecosistemas andinos. Los Andes presentan altos niveles de diversidad y a la vez fuertes presiones ocasionadas por actividades humanas. Así, los parques nacionales son herramientas importantes para la conservación de la biodiversidad. Dentro de este marco, es importante contar con listados completos de las especies que ocupan estos territorios. El presente trabajo recoge las principales observaciones ornitológicas en el Parque Nacional Cajas, prov. Azuay, Ecuador, desde 1980. Adicionalmente, se incluye breves descripciones de especies no reportadas previamente en el área, importantes para la conservación y para la región. Las aves son buenos indicadores de calidad de hábitat y un importante componente en actividades turísticas. The tropical Andes harbour the largest number CNP4. In 1986–87, a British expedition, headed by J. of endemic and threatened bird species in R. King & F. Robinson, focused on MR, undertaking South America45,46. In Ecuador habitat loss is biological inventories and publishing the first widespread46,51 and those natural habitats checklist of birds25,40. Two field guides to the birds that remain are under pressure from human of MR were published in the 1990s41,49 along with activities23,44. Consequently, protected areas an introductory guide to the birds of cloud forests in such as national parks are powerful tools in the Azuay1. -

WWT Conservation Report 2008–2009

WWT Conservation Report 2008 –2009 Weighing a Madagascar Pochard duckling CONTENTS Garth Cripps FOREWORD .......................................................5 Wetland treatment systems ....................... 46 The creation of Lady Fen – PARTNERS AND DONORS ................................8 a wet grassland for Wigeon ................... 49 Planning for the future – STAFF LIST ...................................................... 11 managed realignment feasibility ........... 50 SPECIES CONSERVATION ............................... 13 Enhancing and demonstrating the benefits of wetlands ....................................... 53 Survey, monitoring and setting Clean water for people and wildlife priorities for conservation ............................. 14 in Laos .................................................... 53 Greylag Goose monitoring .......................... 15 Managing wetlands for sustainable Bewick’s Swan population declines ........... 16 livelihoods at Koshi Tappu Wildlife Aerial surveys of waterbirds Reserve, Nepal ....................................... 54 in UK inshore waters ............................. 18 Capacity building for natural resource Capacity building for monitoring management in Guyana ......................... 56 overseas ................................................. 21 Wetlands In My Back Yard (WIMBY) ........... 58 Birds of Conservation Concern .................. 22 Assessing the benefits of IUCN CONSERVATION ADVOCACY ........................... 61 guidelines for waterbird Water and energy re-introduction