Historicalmaterialism Bookseries

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ecuador and the Galapagos Islands

GEODYSSEY ECUADOR AND THE GALAPAGOS ISLANDS Travel guides to Ecuador and the Galapagos Islands Planning your trip Where to stay Private guided touring holidays Small group holidays Galapagos cruises Walking holidays Specialist birdwatching ECUADOR 05 Ecuador Guide 22 Private guided touring 28 Small group holidays Ecuador has more variety packed into a Travel with a guide for the best of Ecuador Join a convivial small group holiday smaller space than anywhere else in South 22 Andes, Amazon and Galapagos 28 Ecuador Odyssey America The classic combination Ecuador's classic highlights in a 2 week 05 Quito fully escorted small group holiday 22 A Taste of Ecuador Our guide to one of Latin America's most A few days on the mainland before a remarkable cities 30 Active Ecuador Galapagos cruise 30 07 Where to stay in Quito Ecuador Adventures ð 23 Haciendas of Distinction Plenty of action for lively couples, friends Suggestions from amongst our favourites Discover the very best and active families 09 Andes 23 Quito City Break 31 Trek to Quilotoa Snow-capped volcanoes, fabulous scenery, Get to know Quito like a native Great walking staying at rural guesthouses llamas and highland communities 24 Nature lodges 32 Day Walks in the Andes 13 Haciendas and hotels for touring ð ð Lodges for the best nature experiences Explore and get fit on leg-stretching day Country haciendas and fine city hotels walks staying in comfortable hotels 25 15 Amazon Creature Comforts Wonderful nature experiences in 33 Cotopaxi Ascent The lushest and most interesting part of -

Dictionary of Norfolk Furniture Makers 1 700-1 840

THE DICTIONARY NORFOLK FURNITURE MAKERS 1700-1840 ABEL, Anthony, cm, 5 Upper Westwick Street, Free [?by purchase] 21/9/1664. Norwich (1778-1802). P 1734 (sen.). 1/12/1778 Apprenticed to Jonathan Hales, King’s ALLOYCE, Abraham jun., tur, St Lawrence, Lynn, £50 (5 yrs). Norwich (1695-1735). D1802. Free 4/3/1695 as s.o. Abraham Alloyce. ABEL, Daniel, up, Pottergate Street; then Bedford P 1710, 1714. 1734 (jun.). 1734/5 - supplement Street, Norwich (1838-1868). (Aloyce). These entries may be for A.A. sen. apart Apprenticed to Thomas Bennett. Free 25/7/1838. from 1734 where both are entered. D 1852, 1854 - cm up, Pottergate St. 1864, 1868 ALLURED, John, up, Market Place, Yarmouth - Bedford St., St Andrews. (1783-1797). ABEL, Thomas, cm, Pitt Street, Norwich App to William Seaman 19/3/1783* (James (1839-1842). D 1839, 1842. Allured), free 15/6/1790. ADCOCK, John, joi, St. Andrew, Norwich Took app William Lyall, 25/12/1790, £40 (5 yrs); (1715-1735). George Allured, 15/12/1792, £20. 28/4/1715 Apprenticed to Charles King, £4. Free NC 5/8/1797: ...John Allured, the younger, of 15/8/1722 as son of Thomas Adcock, tailor. Great Yarmouth...Upholsterer...declared a P 1734, 1734/5 supplement. Bankrupt. ALDEN, James, cm, Norwich (1814). NC 23/9/1797: Auction...Sept. 26, 1797...[4 NM 3/12/1814: Sunday last was married, at St. d ays]...All the genuine Stock in Trade and Giles’s, Mr. James Alden, cabinet-maker, to Miss Household Furniture of Mr. John Allured, Steavens, both of this city. -

DUTCH and ENGLISH PAINTINGS Seascape Gallery 1600 – 1850

DUTCH AND ENGLISH PAINTINGS Seascape Gallery 1600 – 1850 The art and ship models in this station are devoted to the early Dutch and English seascape painters. The historical emphasis here explains the importance of the sea to these nations. Historical Overview: The Dutch: During the 17th century, the Netherlands emerged as one of the great maritime oriented empires. The Dutch Republic was born in 1579 with the signing of the Union of Utrecht by the seven northern provinces of the Netherlands. Two years later the United Provinces of the Netherlands declared their independence from the Spain. They formed a loose confederation as a representative body that met in The Hague where they decided on issues of taxation and defense. During their heyday, the Dutch enjoyed a worldwide empire, dominated international trade and built the strongest economy in Europe on the foundation of a powerful merchant class and a republican form of government. The Dutch economy was based on a mutually supportive industry of agriculture, fishing and international cargo trading. At their command was a huge navy and merchant fleet of fluyts, cargo ships specially designed to sail through the world, which controlled a large percentage of the international trade. In 1595 the first Dutch ships sailed for the East Indies. The Dutch East Indies Company (the VOC as it was known) was established in 1602 and competed directly with Spain and Portugal for the spices of the Far East and the Indian subcontinent. The success of the VOC encouraged the Dutch to expand to the Americas where they established colonies in Brazil, Curacao and the Virgin Islands. -

Norton Marshes to Haddiscoe Dismantled

This area inspired the artist Sir J. A. Arnesby 16 Yare Valley - Norton Marshes to Brown (1866-1955) who lived each summer Haddiscoe Dismantled Railway at The White House, Haddiscoe. Herald of the Night, Sir J.A.Arnesby-Brown Why is this area special? This is a vast area of largely drained marshland which lies to the south of the Rivers Yare and Waveney. It traditionally formed part of the parishes of Norton (Subcourse), Thurlton, Thorpe and Haddiscoe along with a detached part of Raveningham. It would have had a direct connection to what is now known as Haddiscoe Island, prior to the construction of the New Cut which connected the Yare and Waveney together to avoid having to travel across Breydon Water. There are few houses within this marshland area. Those that exist are confined to those locations 27 where there were, or are transport links across NORFOLK the rivers. The remainder of the settlements have 30 28 developed in a linear way hugging the edges of the southern river valley side. 22 31 23 29 The Haddiscoe Dam road provides the main 24 26 connection north-south from Haddiscoe village to 25 NORWICH St Olaves. 11 20 Gt YARMOUTH 10 12 19 21 A journey on the train line from Norwich to 14 9 Lowestoft which follows the line of the New Cut 13 15 18 16 and then hugs the northern side of the Waveney 17 Valley provides a glorious way to view this area as 8 7 public rights of way into the middle of the marshes LOWESTOFT 6 4 (other than the fully navigable river) are few and 2 3 1 5 far between. -

Benefice Profile the Acle and Bure to Yare Benefice

Benefice Profile The Acle and Bure to Yare Benefice The Parishes of Acle Beighton with Moulton, Halvergate with Tunstall, Wickhampton, Freethorpe, Limpenhoe, Southwood & Cantley and Reedham. (February 2019) 1 Contents SECTION 1 The benefice and its seven parishes: where it is and what it’s like p.3 The Benefice / Benefice Life p.4 Facilities and Villages p.6 The Ministry Team / Occasional Offices and other statistics SECTION 2 The Parish Churches: Buildings and Communities. p.7 Acle / p.8 Beighton / p.9 Freethorpe / p.10 Halvergate with Tunstall p.11 Limpenhoe, Southwood & Cantley / p.12 Reedham / p.13 Wickhampton SECTION 3 Deanery and Diocese p.14 SECTION 4 The qualities we are looking for in a priest p.14 Annex I Contact details p.16 Annex II Reedham Rectory p.16 Summary We are seeking applicants for a House for Duty Assistant Priest, resident in Reedham, Norfolk, to join the Ministry Team led by the Revd Martin Greenland, resident in Acle and Rector of the benefice. The focus of the post is to be developed in consultation with the successful applicant (see p.15) – we look forward to hearing what you might bring to enhance what we are already doing, together and in the individual parishes. In the meantime this profile gives a picture of the whole benefice, which comprises seven parishes in rural Norfolk. Styles of worship vary, but common themes of an ecumenical approach, community engagement, links with schools and great potential for use of church buildings emerge from our profile. We are seeking a priest who has a gift for outreach and the energy and personality to attract younger generations to the Church. -

Your Norfolk Broads Adventure Starts Here... Local Tourist Information Skippers Manual

Your Norfolk Broads Adventure Starts Here... Local Tourist Information Skippers Manual #HerbertWoodsHols Contents 1. Responsibilities 7. Signage and Channel Markers 2. Safety on Board 8. Bridges 2.1 Important Information 8.1 Bridge Drill 2.2 Life Jackets 8.2 Bridges Requiring Extra Care 2.3 On Deck 2.4 Getting Aboard & Ashore 9. Locations Requiring Extra Care 2.5 Fending Off 2.6 Cruising Along 9.1 Great Yarmouth 2.7 Man Overboard! 9.2 Crossing Breydon Water 2.8 Yachts 9.3 Reedham Ferry 3. Rules of the Waterways 3.1 Bylaws 10. Tides and Tide Tables 3.2 The Broadland code 3.3 Boating Terms and Equipment 11. Dinghy Sailing 4. Living on Board 4.1 Fresh & Filtered Water 12. Fishing 4.2 Hot Water & Showers 4.3 Electricity 4.4 Toilets 13. Journey Times 4.5 Bottled Gas & Cooking 4.6 Ventilation 14. Emergency Telephone Numbers 4.7 Heating Systems Cruiser Terms and Conditions 4.8 Power Failures 4.9 Fire Extinguisher 4.10 Television 4.11 Roofs & Canopies 15. Broads Authority Notices 4.12 Daily Checks Go Safely Mooring 5. Accident Procedure Bridges Crossing Breydon Water 5.1 Collision Rowing 5.2 Running Aground Sailing 5.3 Mechanical Failure Angling 6. Driving Your Boat 6.1 Starting the Engine 6.2 Casting Off 16. Gas Safety Inspection 6.3 How to Slow and Stop 6.4 Steering 6.5 Reversing 6.6 Mooring 1. Responsibilities As the hirer of this cruiser you have certain responsibilities which include: • Nominating a party leader (The Skipper, who may not be the same person who made the booking). -

The Norwich School John Old Crome John Sell Cotman George Vincent

T H E NO RW I CH SCH OOL JOH N “ OLD ” CROME JOH N SELL c o TMAN ( ) , G E OR G E ‘D I N C E N T JA ME A , S S T RK 1 B N Y C OM JOHN I T . E E E R R , TH R LE D BROOKE D A ’DI D H OD N R. LA , GSO ? J J 0 M. E . 0TM 89 . g/{N E TC . WITH ARTI LES BY M UND ALL C H . C P S A , . CONT ENTS U A P S A R I LES BY H M C ND LL . A T C . , Introduction John Crome John Sell Cotman O ther Members of the Norwich School I LLUSTRATIONS I N COLOURS l Cotman , John Sel Greta rid Yorkshire t - B ge, (wa er colour) Michel Mo nt St. Ruined Castle near a Stream B oats o n Cromer Beach (oil painting) Crome , John The Return ofthe Flock— Evening (oil painting) The Gate A athin Scene View on the Wensum at Thor e Norivtch B g p , (oil painting) Road with Pollards ILLUSTRAT IONS IN MONOTONE Cotman , John Joseph towards Norwich (water—colour) lx x vu Cotman , John Sell rid e Valle and Mountain B g , y, Llang ollen rid e at Sa/tram D evo nshire B g , D urham Castle and Cathedral Windmill in Lincolnshire D ieppe Po wis Cast/e ‘ he alai d an e t Lo T P s e Justic d the Ru S . e , Ro uen Statue o Charles I Chart/2 Cross f , g Cader I dris Eto n Colleg e Study B oys Fishing H o use m th e Place de la Pucelle at Rouen Chdteau at Fo ntame—le— en i near aen H r , C Mil/hank o n the Thames ILLUSTRATIONS IN MONOTONE— Continued PLATE M Cotman , iles Edmund Boats on the Medway (oil painting) lxxv Tro wse Mills lxxvi Crome , John Landscape View on th e Wensum ath near o w ch Mousehold He , N r i Moonlight on the Yare Lands cape : Grov' e Scene The Grove Scene Marlin o rd , gf The Villag e Glade Bach o the Ne w Mills Norwich f , Cottage near L ahenham Mill near Lahenham On th e Shirts of the Forest ive orwich Bach R r, N ru es Ri'ver Ostend in the D istance B g , ; Moo nlight Yarmouth H arho ur ddes I tal e s Parts 1 oulevar i n 1 8 . -

After the Norwich School

After the Norwich School This book takes, as its starting point, sites that feature in paintings, or prints, made by Norwich School artists. For each site I have photographed a contemporary landscape scene. My aim was not to try to replicate the scene painted in the 1800s, but simply to use that as the point where I would take the photograph, thus producing a picture of Norwich today. IMPORTANT This ebook has been produced as part of my studies with OCA for the landscape photography module of my Creative Arts degree course. It is not set to be published, but simply to allow my tutors, assessors and fellow students to see, judge and comment on my work. I am grateful that Norfolk Museums Service allow images to be downloaded for such educational use and I am pleased to credit © Norfolk Museums Service for each of the Norwich School painters images that I have used Robert Coe OCAStudent ID 507140 Proof Copy: Not optimised for high quality printing or digital distribution View on the River Wensum After 'View on the River Wensum, King Street, Norwich' by John Thirtle (1777-1839), pencil and watercolour on paper, undated; 25.8 cm x 35.2 cm © Norfolk Museums Service Proof Copy: Not optimised for high quality printing or digital distribution Proof Copy: Not optimised for high quality printing or digital distribution Proof Copy: Not optimised for high quality printing or digital distribution Briton's Arms, Elm Hill After 'Briton's Arms' by Henry Ninham (1793-1874), watercolour on paper, © Norfolk Museums Service Proof Copy: Not optimised for high -

Wherryman's Way Circular Walks

Brundall Wherryman’s Way Circular Walks Surlingham Postwick Ferry House To Coldham Hall Tavern Bird Hide Surlingham Church Marsh R.S.P.B. Nature Reserve St Saviours Church (ruin) Surlingham To Whitlingham River Yare Surlingham Parish Church To Ted Ellis Trust at Wheatfen Nature Reserve Bramerton To Rockland St Mary 2 miles To Norwich 4 miles Norfolk County Council Contents Introduction page 2 Wherries and wherryman page 3 Circular walks page 4 Walk 1 Whitlingham page 6 Walk 2 Bramerton page 10 Walk 3 Surlingham page 14 Walk 4 Rockland St Mary page 18 Walk 5 Claxton page 22 Walk 6 Langley with Hardley page 26 Wherryman’s Way map page 30 Walk 7 Chedgrave page 32 Walk 8 Loddon page 36 Walk 9 Loddon Ingloss page 40 If you would like this document in large print, audio, Braille, Walk 10 Loddon – Warren Hills page 44 alternative format or in a Walk 11 Reedham page 48 different language please contact Paul Ryan on 01603 Walk 12 Berney Arms page 52 223317, minicom 01603 223833 or [email protected] Project information page 56 1 Introduction Wherries and wherrymen Wherryman’s Way Wherries have been part of life in the Broads for hundreds of years. The Wherryman’s Way is in the Broads, which is Britain’s largest protected Before roads and railways, waterways were the main transport routes wetland. The route passes through many nature reserves and Sites of for trade and people. River trade – the ability to bring in raw materials Special Scientific Interest, a reflection of the rich wildlife diversity of the and export finished goods – helped make Norwich England’s second city, Yare Valley. -

EDP 25Th Sep 2014 Paint out Launches

14 THURSDAY, SEPTEMBER 25, 2014 Eastern Daily Press Like us at: NEWS local www.facebook.com/edp24 Norwich landmarks are the inspiration for artists in new painting competition Emma Knights [email protected] Artistic connections More than Paint Out Norwich is building on the 30 artists city’s long connection with art, including have been the Norwich School of artists who were selected to Media Partners: Eastern Daily Press famous for creating take part in work inspired by an open air event celebrating our city and Norwich in paint. county in the The inaugural Paint Out nineteenth Norwich – part of this year’s century. Hostry Festival – is a two-day en The Norwich plein air painting competition School of which takes its inspiration from artists’ two seven Norwich landmarks. great masters Norwich Castle, Norwich were John Cathedral, The Cathedral of St Crome and John the Baptist, Pull’s Ferry, Elm John Sell Hill, and Norwich Market are all Cotman, (pic- set to be the subjects of the compe- tured), with Crome tition – and The Forum has now best known as an oil been added to the list. painter and Cotman best known for his Following a call-out to artists watercolours. Other artists who were part earlier this year, a group of 31 have of the Norwich School included James now been chosen and will be out Stark, John Berney Crome, George and about in the city with their Vincent, Robert Ladbrooke, James Sillett, ■ Paint Out Norwich artist Leon Bunnewell’s painting, Forum at Night. Pictures: SUBMITTED paintbrushes and easels on October John Thirtle, John Joseph Cotman, 22 and 23. -

How to Charge Your Electric Boat

from River Bure from via Ranworth Dam Rockland Cantley Broad Rocklandfactory Broad from Brundall jetties Rockland Dyke Rockland St Mary post office Malthouse & stores Ranworth Broad public house moorings public house Granary Stores Cantley factory from Stokesby Brundall The Green Riverside Stores public house from Acle Bridge pontoon from Yarmouth Hardley Windmill from Stokesby Yacht Station from Reedham & River chet them? use I do How Reedham pontoon cards? charging get I can Where Breydon Bridge HardleyQuay Windmill Rangers Lord Nelson information hut public house points? charging the are Where public house Yarmouth/Acle post office from Road Bridge Breydon yellow post your electric boat electric your Water boatyards from Breydon Vauxhall Bridge swing bridge Water & How to charge charge to How from ReedhamHaddiscoe Great Yarmouth & River chetNew Cut from Reedham Ferry Dangerous currents & River Chet No hire boats River Bure River Wensum River Chet public house post office Coltishall Bishop Bridge - No hire boats weir - limit of navigation from beyond here River Yare public house Loddon Coltishall Common moorings Norwich post office boatyards Rosy Lee's Tea Room Loddon Basin moorings from Horstead Norwich shops from Wroxham Yacht Station hotel Foundry Bridge from Coltishall Hoveton River Waveney railway bridge turning basin pubs, restaurants, cinema Riverside Park Bridge Broad from Breydon Water Broads information centre from Whitlingham bar & restaurant boatyard boatyard Wroxham Bridge Novi Sad Bridge suspension Wroxham Burgh Castle -

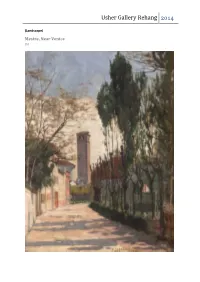

Usher Gallery Rehang 2014

Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 (Landscape) Mestre, Near Venice Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 (Landscape) Church of St. Maria Della Salute, c.1885 Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 (Landscape) Venice Oil (Landscape) Venice Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 (Still Life) Flowers in a Persian Bottle Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 (Still Life) Daffodils Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 (Still Life) Garden Flowers Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 Michiel Jansz. van Miereveldt – (1 May 1567 – 27 June 1641) About The artist, Michiel Jansz. van Miereveldt was born in the Delft and was one of the most successful Dutch portraitists of the 17th century. His works are predominantly head and shoulder portraits, often against a monochrome background. The viewer is drawn towards the sitter’s face by light accents revealed by clothing. After his initial training, Mierevelt quickly turned to portraiture. He gained success in this medium, becoming official painter of the court and gaining many commissions from the wealthy citizens of Delft, other Dutch nobles and visiting foreign dignitaries. His portraits display his characteristic dry manner of painting, evident in this work where the pigment has been applied without much oil. The elaborate lace collar and slashed doublet are reminiscent of clothes that appear in Frans Hals's work of the same period. Work in The Usher Gallery (Portrait) Maria Van Wassenaer Hanecops Oil Usher Gallery Rehang 2014 Mary Henrietta Dering Curtois – (1854 - 6 October 1928) About Mary Henrietta Dering Curtois was born at the Longhills, Branston, in 1854 and was the eldest daughter of the late Rev Atwill Curtois (for 21 years Rector of Branston and the fifth of the family to be rector there), and a brother of the Rev Algernon Curtois of Lincoln.