Historic Jerusalem Challenges and Proposals for Interim Steps

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Development of Modern Sacred Geography: Jerusalem's Holy Basin

Electronic Working Papers Series www.conflictincities.org/workingpapers.html Divided Cities/Contested States Working Paper No. 19 The Development of Modern Sacred Geography: Jerusalem’s Holy Basin Wendy Pullan and Maximilian Gwiazda Department of Architecture University of Cambridge Conflict in Cities and the Contested State: Everyday life and the possibilities for transformation in Belfast, Jerusalem and other divided cities UK Economic and Social Research Council Large Grants Scheme, RES-060-25-0015, 2007-2012. Divided Cities/Contested States Working Paper Series www.conflictincities.org/workingpapers.html Editor: Prof James Anderson Associate Editors: Prof Mick Dumper, Prof Liam O'Dowd and Dr Wendy Pullan Editorial Assistant: Dr Milena Komarova Correspondence to: [email protected]; [email protected] [Comments on published Papers and the Project in general are welcomed at: [email protected] ] THE SERIES 1. From Empires to Ethno-national Conflicts: A Framework for Studying ‘Divided Cities’ in ‘Contested States’ – Part 1, J. Anderson, 2008. 2. The Politics of Heritage and the Limitations of International Agency in Divided Cities: The role of UNESCO in Jerusalem’s Old City, M. Dumper and C. Larkin, 2008. 3. Shared space in Belfast and the Limits of A Shared Future, M. Komarova, 2008. 4. The Multiple Borders of Jerusalem: Implications for the Future of the City, M. Dumper, 2008. 5. New Spaces and Old in ‘Post-Conflict’ Belfast, B. Murtagh, 2008. 6. Jerusalem’s City of David’: The Politicisation of Urban Heritage, W. Pullan and M. Gwiazda, 2008. 7. Post-conflict Reconstruction in Mostar: Cart Before the Horse, Jon Calame and Amir Pasic, 2009. -

Temple in Jerusalem Coordinates: 31.77765, 35.23547 from Wikipedia, the Free Encyclopedia

Log in / create account article discussion edit this page history Temple in Jerusalem Coordinates: 31.77765, 35.23547 From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia Bet HaMikdash ; "The Holy House"), refers to Part of a series of articles on ,שדקמה תיב :The Temple in Jerusalem or Holy Temple (Hebrew a series of structures located on the Temple Mount (Har HaBayit) in the old city of Jerusalem. Historically, two Jews and Judaism navigation temples were built at this location, and a future Temple features in Jewish eschatology. According to classical Main page Jewish belief, the Temple (or the Temple Mount) acts as the figurative "footstool" of God's presence (Heb. Contents "shechina") in the physical world. Featured content Current events The First Temple was built by King Solomon in seven years during the 10th century BCE, culminating in 960 [1] [2] Who is a Jew? ∙ Etymology ∙ Culture Random article BCE. It was the center of ancient Judaism. The Temple replaced the Tabernacle of Moses and the Tabernacles at Shiloh, Nov, and Givon as the central focus of Jewish faith. This First Temple was destroyed by Religion search the Babylonians in 587 BCE. Construction of a new temple was begun in 537 BCE; after a hiatus, work resumed Texts 520 BCE, with completion occurring in 516 BCE and dedication in 515. As described in the Book of Ezra, Ethnicities Go Search rebuilding of the Temple was authorized by Cyrus the Great and ratified by Darius the Great. Five centuries later, Population this Second Temple was renovated by Herod the Great in about 20 BCE. -

The Straight Path: Islam Interpreted by Muslims by Kenneth W. Morgan

Islam -- The Straight Path: Islam Interpreted by Muslims return to religion-online 47 Islam -- The Straight Path: Islam Interpreted by Muslims by Kenneth W. Morgan Kenneth W. Morgan is Professor of history and comparative religions at Colgate University. Published by The Ronald Press Company, New York 1958. This material was prepared for Religion Online by Ted and Winnie Brock. (ENTIRE BOOK) A collection of essays written by Islamic leaders for Western readers. Chapters describe Islam's origin, ideas, movements and beliefs, and its different manifestations in Africa, Turkey, Pakistan, India, China and Indonesia. Preface The faith of Islam, and the consequences of that faith, are described in this book by devout Muslim scholars. This is not a comparative study, nor an attempt to defend Islam against what Muslims consider to be Western misunderstandings of their religion. It is simply a concise presentation of the history and spread of Islam and of the beliefs and obligations of Muslims as interpreted by outstanding Muslim scholars of our time. Chapter 1: The Origin of Islam by Mohammad Abd Allah Draz The straight path of Islam requires submission to the will of God as revealed in the Qur’an, and recognition of Muhammad as the Messenger of God who in his daily life interpreted and exemplified that divine revelation which was given through him. The believer who follows that straight path is a Muslim. Chapter 2: Ideas and Movements in Islamic History, by Shafik Ghorbal The author describes the history and problems of the Islamic society from the time of the prophet Mohammad as it matures to modern times. -

Volume 48, Number 1, Spring

Volume 48, Number 1 Spring 1998 IN THIS ISSUE Rx for ASOR: Shanks May be Right! Lynch's Expedition to the Dead Sea News & Notices Tall Hisban 1997 Tell Qarqur 1997 Project Descriptions of Albright Appointees Endowment for Biblical Research Grant Recipient Reports Meeting Calendar Calls for Papers Annual Meeting Information E-mail Directory Rx for ASOR: SHANKS MAY BE RIGHT! If any would doubt Herschel Shanks' support for ASOR and its work mark this! His was among the earliest contributions received in response to our 1997-98 Annual Appeal and he was the very first person to register for the 1998 fall meeting in Orlando! So I urge everyone to give a serious reading to his post-mortem on "The Annual Meeting(s)" just published in Biblical Archaeology Review 24:2 (henceforth BAR). Like most spin doctors his "Rx for ASOR" (p. 6) and "San Francisco Tremors" (p. 54) are burdened with journalistic hyperbole, but within and beyond the hype he scores a number of valid points. However, while several of his comments warrant repetition and review, a few others need to be corrected and/or refocused. ASOR's constituency does indeed, as he notes (BAR p. 6), represent a broad spectrum of interests. These reach from Near Eastern prehistory to later classical antiquity and beyond, and from a narrower focus on bible related material culture to a broader concern with the full range of political and cultural entities of the Ancient Near East and of the eastern and even western Mediterranean regions. Throughout its nearly 100 year history, by initiating and supporting field excavation efforts, by encouraging scholarly and public dialogue via an active publications program, and through professional academic meetings, ASOR's mission has included service to all facets of this wide spectrum. -

Tankiz Ibn ʿabd Allāh Al-Ḥusāmī Al-Nāṣirī (D

STEPHAN CONERMANN UNIVERSITY OF BONN Tankiz ibn ʿAbd Allāh al-Ḥusāmī al-Nāṣirī (d. 740/1340) as Seen by His Contemporary al-Ṣafadī (d. 764/1363) INTRODUCTION Many take Hayden White’s “theory of narrativity” to be the beginning of a “change of paradigm,” in the sense of Thomas Kuhn, that indicated the bankruptcy of mechanistic and organic models of truth and explanation. Historians could no longer believe in explanatory systems and monolithic visions of history. 1 From now on, they would prefer the formist or contextualist form of argument, which is more modest and fragmentary. It is thanks to “narrativity” that historians were reminded of their cognitive limits, which had been neglected by positivism and other historiographical trends, and it is thanks to White, and to his Metahistory in particular, that they were reminded of the importance of their medium, language, and of their dependence on the linguistic universe. With the appearance of White’s much-disputed book, the exclusively interlinguistic debate on the so- called “linguistic turn” gained ground among historians. The literary theory which has been developed by Ferdinand de Saussure, Roland Barthes, and Mary Louise Pratt points out that history possesses neither an inherent unity nor an inherent coherence. Every understanding of history is a construct formed by linguistic means. The fact that a human being does not have a homogeneous personality without inherently profound contradictions leads to the inescapable conclusion that every text, as a product of the human imagination, must be read and interpreted in manifold ways: behind its reading and interpretation there is an unequivocal or unambiguous intention. -

Day 7 Thursday March 10, 2022 Temple Mount Western Wall (Wailing Wall) Temple Institute Jewish Quarter Quarter Café Wohl Museu

Day 7 Thursday March 10, 2022 Temple Mount Western Wall (Wailing Wall) Temple Institute Jewish Quarter Quarter Café Wohl Museum Tower of David Herod’s Palace Temple Mount The Temple Mount, in Hebrew: Har HaBáyit, "Mount of the House of God", known to Muslims as the Haram esh-Sharif, "the Noble Sanctuary and the Al Aqsa Compound, is a hill located in the Old City of Jerusalem that for thousands of years has been venerated as a holy site in Judaism, Christianity, and Islam alike. The present site is a flat plaza surrounded by retaining walls (including the Western Wall) which was built during the reign of Herod the Great for an expansion of the temple. The plaza is dominated by three monumental structures from the early Umayyad period: the al-Aqsa Mosque, the Dome of the Rock and the Dome of the Chain, as well as four minarets. Herodian walls and gates, with additions from the late Byzantine and early Islamic periods, cut through the flanks of the Mount. Currently it can be reached through eleven gates, ten reserved for Muslims and one for non-Muslims, with guard posts of Israeli police in the vicinity of each. According to Jewish tradition and scripture, the First Temple was built by King Solomon the son of King David in 957 BCE and destroyed by the Neo-Babylonian Empire in 586 BCE – however no substantial archaeological evidence has verified this. The Second Temple was constructed under the auspices of Zerubbabel in 516 BCE and destroyed by the Roman Empire in 70 CE. -

Mamluk Architectural Landmarks in Jerusalem

Mamluk Architectural Landmarks 2019 Mamluk Architectural in Jerusalem Under Mamluk rule, Jerusalem assumed an exalted Landmarks in Jerusalem religious status and enjoyed a moment of great cultural, theological, economic, and architectural prosperity that restored its privileged status to its former glory in the Umayyad period. The special Jerusalem in Landmarks Architectural Mamluk allure of Al-Quds al-Sharif, with its sublime noble serenity and inalienable Muslim Arab identity, has enticed Muslims in general and Sufis in particular to travel there on pilgrimage, ziyarat, as has been enjoined by the Prophet Mohammad. Dowagers, princes, and sultans, benefactors and benefactresses, endowed lavishly built madares and khanqahs as institutes of teaching Islam and Sufism. Mausoleums, ribats, zawiyas, caravansaries, sabils, public baths, and covered markets congested the neighborhoods adjacent to the Noble Sanctuary. In six walks the author escorts the reader past the splendid endowments that stand witness to Jerusalem’s glorious past. Mamluk Architectural Landmarks in Jerusalem invites readers into places of special spiritual and aesthetic significance, in which the Prophet’s mystic Night Journey plays a key role. The Mamluk massive building campaign was first and foremost an act of religious tribute to one of Islam’s most holy cities. A Mamluk architectural trove, Jerusalem emerges as one of the most beautiful cities. Digita Depa Me di a & rt l, ment Cultur Spor fo Department for e t r Digital, Culture Media & Sport Published by Old City of Jerusalem Revitalization Program (OCJRP) – Taawon Jerusalem, P.O.Box 25204 [email protected] www.taawon.org © Taawon, 2019 Prepared by Dr. Ali Qleibo Research Dr. -

An Alternative Explanation of the Royal and Select Master Degrees

An Alternative Explanation of the Royal and Select Master Degrees by Sir Knight Gene Fricks The legends behind the ritual of the Royal and Select Masters degrees are among those with only a vague basis in biblical antecedents. Unlike the legend of Hiram and the building of the first temple or that of Zerubabbel and the second temple, we have only a passing mention of Adoniram as the first overseer of King Solomon and a listing of Solomon's chief officers in I Kings 4:4. We do not find the secret passageway or the nine arches described in the II Kings story of the temple's construction. Recognizing that the writers of the original rituals were men steeped in classical learning, we should look elsewhere for the source of this story. I suggest that the writings of the 15th century Arab historian, Mudjir ad-Din, may have been that source. What prompted this thought was the celebration of the 3000th anniversary of Jerusalem several years ago and the renewed interest in its ruins that the commemoration sparked. Let us review some of Jerusalem's history after the Roman destruction of Herod's Temple in 70 A.D. to set some background. Titus and his son Vespasian conquered Jerusalem after a long and bloody siege. Determined to bring the recalcitrant Jews to heel, the Roman 10th Legion, left to garrison the city, were ordered to level the temple down to its foundations. What we see today in Jerusalem is the temple mount platform upon which the temple sat, all that remains of Herod's imposing construction project. -

The Temple Mount/Haram Al-Sharif – Archaeology in a Political Context

The Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif – Archaeology in a Political Context 2017 March 2017 Table of contents >> Introduction 3 Written by: Yonathan Mizrachi >> Part I | The history of the Site: How the Temple Mount became the 0 Researchers: Emek Shaveh Haram al-Sharif 4 Edited by: Talya Ezrahi >> Part II | Changes in the Status of the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif 0 Proof-editing: Noa Granot from the 19th century to the Present Day 7 Graphic Design: Lior Cohen Photographs: Emek Shaveh, Yael Ilan >> Part III | Changes around the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif and the 0 Mapping: Lior Cohen, Shai Efrati, Slava Pirsky impact on the Status Quo 11 >> Conclusion and Lessons 19 >> Maps 20 Emek Shaveh (cc) | Email: [email protected] | website www.alt-arch.org Emek Shaveh is an Israeli NGO working to prevent the politicization of archaeology in the context of the Israeli-Palestinian conflict, and to protect ancient sites as public assets that belong to members of all communities, faiths and peoples. We view archaeology as a resource for building bridges and strengthening bonds between peoples and cultures. This publication was produced by Emek Shaveh (A public benefit corporation) with the support of the IHL Secretariat, the Federal Department for Foreign Affairs Switzerland (FDFA) the New Israeli Fund and CCFD. Responsibility for the information contained in this report belongs exclu- sively to Emek Shaveh. This information does not represent the opinions of the above mentioned donors. 2 Introduction Immediately after the 1967 War, Israel’s then Defense Minister Moshe Dayan declared that the Islamic Waqf would retain their authority over the Temple Mount/Haram al-Sharif compound. -

Dangerous Grounds at Al- Haram Al-Sharif

One of the most sacred sites on earth has become Dangerous a place of episodic chaos and cacophony, a Grounds at al- place where hatred and contempt are openly expressed, and where an unequal battle is being Haram al-Sharif: waged over incompatible claims. Spearheaded by “Temple Mount” groups, The Threats to the various Jewish “redemptionists” have mounted Status Quo a calibrated campaign for major unilateral Israeli changes to the Status Quo on the Haram Marian Houk al-Sharif (which Jews prefer to call the Temple Mount) in order to advance toward their goals “millimeter by millimeter”. The time has come, these organizations say, to brush aside what’s left of the inconvenient Status Quo arrangements, inherited from the Ottoman period and adapted by Moshe Dayan in June 1967, which left administration of the mosque esplanade in the hands of the Islamic Waqf (or “Trust Foundation”). The truth is, the Status Quo has already been tweaked a number of times – two of the most dramatic changes were in June 1967, after Israel’s conquest of the West Bank and Gaza, and again on 28 September 2000, when Ariel Sharon wanted to make a point, accompanied by about 1,000 armed Israeli soldiers and police. A third moment of change is occurring as this is written, with Israeli officials ordering the exclusion of Palestinian Muslim worshippers in order to make the Jewish visitors more comfortable, and Palestinians desperately trying to devise strategies to retain their acquired rights. What exists, now, on any given day, is a precarious balance of political and diplomatic interests as defined at any given moment by Israel’s Prime Minister Benyamin Netanyahu. -

02 Jerusalem

Chapter II A New Inscription from the Haram al-Sharif in Jerusalem* The great Muslim sanctuary of the Haram al-Sharif is remarkable, among many things, for the two facts that its physical appearance and general layout were imposed, to a large extent, by the older and still controversial history of the area, and that, with the partial exception of the Dome of the Rock, its monuments have often changed their significance or physical character. Even though most of the literary sources dealing with Jerusalem are fairly conveniently accessible and the inscriptions masterfully published by Max van Berchem, the actual history of the site and of its different parts has not yet been fully written. Either we have short summaries, rarely dealing in any detail with the period which followed the Crusades, or, as in the case of Max van Berchem’s Matériaux pour un Corpus Inscriptionum Arabicarum, the problems are posed and solved in relation to a certain kind of documentation, for instance inscriptions, and a complete view of the evolution of the site does not always emerge. This complete view will not be achieved without precise studies of individual parts of the Haram. In this brief commentary on a newly discovered inscription an attempt will be made to discuss and solve problems posed by the topography of the Haram. The inscription is repeated five times on long, narrow (3.68 by 0.14 meters) brass bands affixed with heavy nails on the two wooden doors of the Bab al-Qattanin (Figure 1), one of the most austere gates of the Haram leading to the suq of the cotton-merchants, now unfortunately abandoned. -

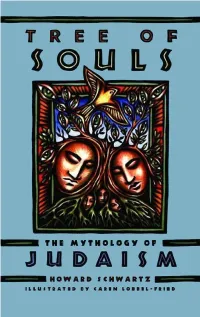

Tree of Souls: the Mythology of Judaism

96 MYTHS OF CREATION 124. THE PILLARS OF THE WORLD The world stands upon pillars. Some say it stands on twelve pillars, according to the number of the tribes of Israel. Others say that it rests on seven pillars, which stand on the water. This water is on top of the mountains, which rest on wind and storm. Still others say that the world stands on three pillars. Once every three hundred years they move slightly, causing earthquakes. But Rabbi Eleazar ben Shammua says that it rests on one pillar, whose name is “Righteous.” One of the ancient creation myths found in many cultures describes the earth as standing on one or more pillars. In this Jewish version of the myth, several theories are found—that the earth stands on twelve, seven, or three pillars—or on one. Rabbi Eleazar ben Shammua gives that one pillar the name of Tzaddik, “Righteous,” under- scoring an allegorical reading of this myth, whereby God is the pillar that supports the world. This, of course, is the central premise of monotheism. Alternatively, his comment may be understood to refer to the Tzaddik, the righteous man whose exist- ence is required for the world to continue to exist. Or it might refer to the principle of righteousness, and how the world could not exist without it. Sources: B. Hagigah 12b; Me’am Lo’ez on Genesis 1:10. 125. THE FOUNDATION STONE The world has a foundation stone. This stone serves as the starting point for all that was created, and serves as a true foundation.