The Men of Cheshire and the Rebellion of 14031

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

For God's Sake, Let Us Sit Upon the Ground and Tell Sad Stories of the Death of Kings … -Richard II, Act III, Scene Ii

The Hollow Crown is a lavish new series of filmed adaptations of four of Shakespeare’s most gripping history plays: Richard II , Henry IV, Part 1 , Henry IV, Part 2 , and Henry V , presented by GREAT PERFORMANCES . For God's sake, let us sit upon the ground and tell sad stories of the death of kings … -Richard II, Act III, Scene ii 2013 WNET Synopsis The Hollow Crown presents four of Shakespeare’s history plays: Richard II , Henry IV, Parts 1 and 2, and Henry V . These four plays were written separately but tell a continuous story of the reigns of three kings of England. The first play starts in 1398, as King Richard arbitrates a dispute between his cousin Henry Bolingbroke and the Duke of Norfolk, which he resolves by banishing both men from England— Norfolk for life and Bolingbroke for six years. When Bolingbroke’s father dies, Richard seizes his lands. It’s the latest outrage from a selfish king who wastes money on luxuries, his favorite friends, and an expensive war in Ireland. Bolingbroke returns from banishment with an army to take back his inheritance and quickly wins supporters. He takes Richard prisoner and, rather than stopping at his own lands and privileges, seizes the crown. When one of Bolingbroke’s followers assassinates Richard, the new king claims that he never ordered the execution and banishes the man who killed Richard. Years pass, and at the start of Henry IV, Part 1 , the guilt-stricken king plans a pilgrimage to the Holy Land to wash Richard’s blood from his hands. -

King and Country: Shakespeare’S Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company

2016 BAM Winter/Spring #KingandCountry Brooklyn Academy of Music Alan H. Fishman, Chairman of the Board William I. Campbell, Vice Chairman of the Board BAM, the Royal Shakespeare Company, and Adam E. Max, Vice Chairman of the Board The Ohio State University present Katy Clark, President Joseph V. Melillo, Executive Producer King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings Richard II • Henry IV Part I Henry IV Part II • Henry V Royal Shakespeare Company BAM Harvey Theater Mar 24—May 1 Season Sponsor: Directed by Gregory Doran Set design by Stephen Brimson Lewis Global Tour Premier Partner Lighting design by Tim Mitchell Music by Paul Englishby Leadership support for King and Country Sound design by Martin Slavin provided by the Jerome L. Greene Foundation. Movement by Michael Ashcroft Fights by Terry King Major support for Henry V provided by Mark Pigott KBE. Major support provided by Alan Jones & Ashley Garrett; Frederick Iseman; Katheryn C. Patterson & Thomas L. Kempner Jr.; and Jewish Communal Fund. Additional support provided by Mercedes T. Bass; and Robert & Teresa Lindsay. #KingandCountry Royal Shakespeare Company King and Country: Shakespeare’s Great Cycle of Kings BAM Harvey Theater RICHARD II—Mar 24, Apr 1, 5, 8, 12, 14, 19, 26 & 29 at 7:30pm; Apr 17 at 3pm HENRY IV PART I—Mar 26, Apr 6, 15 & 20 at 7:30pm; Apr 2, 9, 23, 27 & 30 at 2pm HENRY IV PART II—Mar 28, Apr 2, 7, 9, 21, 23, 27 & 30 at 7:30pm; Apr 16 at 2pm HENRY V—Mar 31, Apr 13, 16, 22 & 28 at 7:30pm; Apr 3, 10, 24 & May 1 at 3pm ADDITIONAL CREATIVE TEAM Company Voice -

Early Methodism in and Around Chester, 1749-1812

EARIvY METHODISM IN AND AROUND CHESTER — Among the many ancient cities in England which interest the traveller, and delight the antiquary, few, if any, can surpass Chester. Its walls, its bridges, its ruined priory, its many churches, its old houses, its almost unique " rows," all arrest and repay attention. The cathedral, though not one of the largest or most magnificent, recalls many names which deserve to be remembered The name of Matthew Henry sheds lustre on the city in which he spent fifteen years of his fruitful ministry ; and a monument has been most properly erected to his honour in one of the public thoroughfares, Methodists, too, equally with Churchmen and Dissenters, have reason to regard Chester with interest, and associate with it some of the most blessed names in their briefer history. ... By John Wesley made the head of a Circuit which reached from Warrington to Shrewsbury, it has the unique distinction of being the only Circuit which John Fletcher was ever appointed to superintend, with his curate and two other preachers to assist him. Probably no other Circuit in the Connexion has produced four preachers who have filled the chair of the Conference. But from Chester came Richard Reece, and John Gaulter, and the late Rev. John Bowers ; and a still greater orator than either, if not the most effective of all who have been raised up among us, Samuel Bradburn. (George Osborn, D.D. ; Mag., April, 1870.J Digitized by tine Internet Arciiive in 2007 with funding from IVIicrosoft Corporation littp://www.archive.org/details/earlymethodisminOObretiala Rev. -

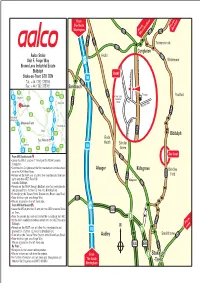

Stoke-On-Trent ST8 7DN A

From The North From Warrington Buxton A54 From A54 MacclesfieldA34 A50 Timbersbrook A5022 A534 Congleton Aalco Stoke Arclid A527 J17 T Whitemoor Unit F, Forge Way u n s Brown Lees Industrial Estate t al A34 Biddulph l R Inset y o a Stoke-on-Trent ST8 7DN a W M6 d A533 e Brown Le g Tel: +44 1782 375700 r o Fax: +44 1782 375701 Sandbach F A50 A34 A60 e Texaco Brown Lees s Poolfold M6 Congleton A614 A53 M1 Industrial R Estate oad J17 A6 Mansfield ay A534 ria W Biddulph Victo J28 A533 A38 J16 A52 A527 Newcastle- Under-Lyme J26 ay W J15 Stoke-on-Trent t c Nottingham e p A53 A50 J25 s Derby o r A527 A453 P Biddulph A34 J24 Rode East Midlands A34 Heath Scholar Stafford A46 M6 A38 Green M6 A51 A42 M1 A6 See Inset From M6 Southbound A50 Leave the M6 at junction 17 and join the A534 towards Congleton. A533 Continue into Congleton at the first roundabout continue ahead Alsager Kidsgrove Brindley onto the A34 West Road. Remain on the A34 over a further two roundabouts then turn Ford A527 right onto the A527 Rood Hill. A34 Kidsgrove A50 towards Biddulph. Remain on the A534 through Biddulph over four roundabouts and proceed for a further 1/2 mile into Brindley Ford. Turn right at the Texaco Petrol Station onto Brown Lees Road. Take the first right onto Forge Way. A500 We are situated on the left hand side. From M6 Northbound J16 Leave the M6 at junction 16 and join the A500 towards Stoke A500 on Trent. -

Shakespeare's

Shakespeare’s Henry IV: s m a r t The Shadow of Succession SHARING MASTERWORKS OF ART April 2007 These study materials are produced for use with the AN EDUCATIONAL OUTREACH OF BOB JONES UNIVERSITY Classic Players production of Henry IV: The Shadow of Succession. The historical period The Shadow of Succession takes into account is 1402 to 1413. The plot focuses on the Prince of Wales’ preparation An Introduction to to assume the solemn responsibilities of kingship even while Henry IV regards his unruly son’s prospects for succession as disastrous. The Shadow of When the action of the play begins, the prince, also known as Hal, finds himself straddling two worlds: the cold, aristocratic world of his Succession father’s court, which he prefers to avoid, and the disreputable world of Falstaff, which offers him amusement and camaraderie. Like the plays from which it was adapted, The Shadow of Succession offers audiences a rich theatrical experience based on Shakespeare’s While Henry IV regards Falstaff with his circle of common laborers broad vision of characters, events and language. The play incorporates a and petty criminals as worthless, Hal observes as much human failure masterful blend of history and comedy, of heroism and horseplay, of the in the palace, where politics reign supreme, as in the Boar’s Head serious and the farcical. Tavern. Introduction, from page 1 Like Hotspur, Falstaff lacks the self-control necessary to be a produc- tive member of society. After surviving at Shrewsbury, he continues to Grieved over his son’s absence from court at a time of political turmoil, squander his time in childish pleasures. -

Brindley Archer Aug 2011

William de Brundeley, his brother Hugh de Brundeley and their grandfather John de Brundeley I first discovered William and Hugh (Huchen) Brindley in a book, The Visitation of Cheshire, 1580.1 The visitations contained a collection of pedigrees of families with the right to bear arms. This book detailed the Brindley family back to John Brindley who was born c. 1320, I wanted to find out more! Fortunately, I worked alongside Allan Harley who was from a later Medieval re-enactment group, the ‘Beaufort companye’.2 I asked if his researchers had come across any Brundeley or Brundeleghs, (Medieval, Brindley). He was able to tell me of the soldier database and how he had come across William and Hugh (Huchen) Brundeley, archers. I wondered how I could find out more about these men. The database gave many clues including who their captain was, their commander, the year of service, the type of service and in which country they were campaigning. First Captain Nature of De Surname Rank Commander Year Reference Name Name Activity Buckingham, Calveley, Thomas of 1380- Exped TNA William de Brundeley Archer Hugh, Sir Woodstock, 1381 France E101/39/9 earl of Buckingham, Calveley, Thomas of 1380- Exped TNA Huchen de Brundeley Archer Hugh, Sir Woodstock, 1381 France E101/39/9 earl of According to the medieval soldier database (above), the brothers went to France in 1380-1381 with their Captain, Sir Hugh Calveley as part of the army led by the earl of Buckingham. We can speculate that William and Hugh would have had great respect for Sir Hugh, as he had been described as, ‘a giant of a man, with projecting cheek bones, a receding hair line, red hair and long teeth’.3 It appears that he was a larger than life character and garnered much hyperbole such as having a large appetite, eating as much as four men and drinking as much as ten. -

Henry V Template

OHIO SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL KING HENRY V AUGUST 2015 HISTORICAL CONTEXT QUIZZES & VOCAB ACTOR INSIGHTS READ ABOUT THE TRUE STORY OF FIND PRINTABLE QUOTES QUIZ OSF ACTORS SPEAK ABOUT THEIR HENRY V, THEN COMPARE IT TO THE (WITH TEACHER’S KEY) AND A CHARACTERS COMING ALIVE TAKE SHAKESPEARE CHOOSES TO VOCABULARY LIST WITH THROUGH SHAKESPEARE’S TEXT. TELL. DEFINITIONS. KING HENRY V Historical Context Henry Bolingbroke was king, King Henry IV, first king of the line of Lancaster. His claim to the throne was hotly contested, with powerful noble families “We few, we happy believing that Lord Mortimer, who Richard II named as his heir before his few, we band of death, was the rightful king. The Percy’s, led by Harry ‘Hotspur’ Percy, raised an brothers…” army against Henry IV, meeting him in the famed battle of Shrewsbury. Here, !1 OHIO SHAKESPEARE FESTIVAL KING HENRY V AUGUST 2015 Henry Bolingbroke’s son, Henry of Monmouth (the future Henry V), played a pivotal role in securing victory for the king and crushing O! the Percy rebellion. Henry of Monmouth continued to show his battlefield prowess by quelling a Welsh rebellion led by the mighty for a Muse of Owain Glydwr. fire, that would With the kingdom secured in the year 1408 and the king in ill health, Henry of Monmouth sought a more active role in politics. ascend the The king’s illness gave Henry political control over the country, leaving him free to enact his own policies. These policies differed brightest heaven much from those of the king, who, in 1411 after a recovery from his illness, dismissed Henry from the court and reversed many of his of invention! policies. -

Stories from Shakespeare 3 for Naxos Audiobooks

David Timson STORIES FROM SHAKESPEARE The Plantagenets JUNIOR Read by Anton Lesser and cast CLASSICS 3 CDs WITH EXCERPTS FROM THE PLAYS NA391912 Shakespeare Stories-plantagenets booklet.indd 1 30/9/08 09:12:16 CD 1 1 Richard II 4:34 2 This Royal throne of Kings, this sceptred isle, 1:32 3 Gaunt tried to warn King Richard… 3:43 4 So when this thief, this traitor Bolingbroke… 0:31 5 But Richard’s confidence soon vanished… 2:13 6 The young Duke of Aumerle bade Richard… 2:18 7 And so Richard, with no power left to him… 2:00 8 Here, cousin, seize the crown… 1:36 9 Richard’s grief at his loss overwhelmed him… 0:59 10 In despair, Richard smashed the mirror… 3:11 11 That hand will burn in never-quenching fire… 0:33 12 In his dying moments, ex-King Richard… 0:59 13 Henry IV Part One 1:28 14 The son, who was the theme of honour’s tongue… 0:39 15 Prince Hal, although he was the Prince of Wales… 2:16 16 Prince Hal had another friend… 2:38 17 Hotspur had hoped to strike a deal… 1:23 18 A plague of cowards still, say I… 2:03 19 By the time Falstaff had finished his tale… 1:27 20 But Falstaff’s plans for their evening’s entertainment… 1:46 21 Then Hal and Falstaff swapped parts… 2:29 2 NA391912 Shakespeare Stories-plantagenets booklet.indd 2 30/9/08 09:12:16 CD 1 (cont.) 22 Their play was interrupted by the arrival… 0:30 23 That night at the palace… 1:09 24 I will redeem all this on Percy’s head. -

Battle Name: Campston Hill (June-November 1404?)

MEYSYDD BRWYDRO HANESYDDOL HISTORIC BATTLEFIELDS IN WALES YNG NGHYMRU The following report, commissioned by Mae’r adroddiad canlynol, a gomisiynwyd the Welsh Battlefields Steering Group and gan Grŵp Llywio Meysydd Brwydro Cymru funded by Welsh Government, forms part ac a ariennir gan Lywodraeth Cymru, yn of a phased programme of investigation ffurfio rhan o raglen archwilio fesul cam i undertaken to inform the consideration of daflu goleuni ar yr ystyriaeth o Gofrestr a Register or Inventory of Historic neu Restr o Feysydd Brwydro Hanesyddol Battlefields in Wales. Work on this began yng Nghymru. Dechreuwyd gweithio ar in December 2007 under the direction of hyn ym mis Rhagfyr 2007 dan the Welsh Government’sHistoric gyfarwyddyd Cadw, gwasanaeth Environment Service (Cadw), and followed amgylchedd hanesyddol Llywodraeth the completion of a Royal Commission on Cymru, ac yr oedd yn dilyn cwblhau the Ancient and Historical Monuments of prosiect gan Gomisiwn Brenhinol Wales (RCAHMW) project to determine Henebion Cymru (RCAHMW) i bennu pa which battlefields in Wales might be feysydd brwydro yng Nghymru a allai fod suitable for depiction on Ordnance Survey yn addas i’w nodi ar fapiau’r Arolwg mapping. The Battlefields Steering Group Ordnans. Sefydlwyd y Grŵp Llywio was established, drawing its membership Meysydd Brwydro, yn cynnwys aelodau o from Cadw, RCAHMW and National Cadw, Comisiwn Brenhinol Henebion Museum Wales, and between 2009 and Cymru ac Amgueddfa Genedlaethol 2014 research on 47 battles and sieges Cymru, a rhwng 2009 a 2014 comisiynwyd was commissioned. This principally ymchwil ar 47 o frwydrau a gwarchaeau. comprised documentary and historical Mae hyn yn bennaf yn cynnwys ymchwil research, and in 10 cases both non- ddogfennol a hanesyddol, ac mewn 10 invasive and invasive fieldwork. -

Index of Cheshire Place-Names

INDEX OF CHESHIRE PLACE-NAMES Acton, 12 Bowdon, 14 Adlington, 7 Bradford, 12 Alcumlow, 9 Bradley, 12 Alderley, 3, 9 Bradwall, 14 Aldersey, 10 Bramhall, 14 Aldford, 1,2, 12, 21 Bredbury, 12 Alpraham, 9 Brereton, 14 Alsager, 10 Bridgemere, 14 Altrincham, 7 Bridge Traffbrd, 16 n Alvanley, 10 Brindley, 14 Alvaston, 10 Brinnington, 7 Anderton, 9 Broadbottom, 14 Antrobus, 21 Bromborough, 14 Appleton, 12 Broomhall, 14 Arden, 12 Bruera, 21 Arley, 12 Bucklow, 12 Arrowe, 3 19 Budworth, 10 Ashton, 12 Buerton, 12 Astbury, 13 Buglawton, II n Astle, 13 Bulkeley, 14 Aston, 13 Bunbury, 10, 21 Audlem, 5 Burton, 12 Austerson, 10 Burwardsley, 10 Butley, 10 By ley, 10 Bache, 11 Backford, 13 Baddiley, 10 Caldecote, 14 Baddington, 7 Caldy, 17 Baguley, 10 Calveley, 14 Balderton, 9 Capenhurst, 14 Barnshaw, 10 Garden, 14 Barnston, 10 Carrington, 7 Barnton, 7 Cattenhall, 10 Barrow, 11 Caughall, 14 Barthomley, 9 Chadkirk, 21 Bartington, 7 Cheadle, 3, 21 Barton, 12 Checkley, 10 Batherton, 9 Chelford, 10 Bebington, 7 Chester, 1, 2, 3, 6, 7, 10, 12, 16, 17, Beeston, 13 19,21 Bexton, 10 Cheveley, 10 Bickerton, 14 Chidlow, 10 Bickley, 10 Childer Thornton, 13/; Bidston, 10 Cholmondeley, 9 Birkenhead, 14, 19 Cholmondeston, 10 Blackden, 14 Chorley, 12 Blacon, 14 Chorlton, 12 Blakenhall, 14 Chowley, 10 Bollington, 9 Christleton, 3, 6 Bosden, 10 Church Hulme, 21 Bosley, 10 Church Shocklach, 16 n Bostock, 10 Churton, 12 Bough ton, 12 Claughton, 19 171 172 INDEX OF CHESHIRE PLACE-NAMES Claverton, 14 Godley, 10 Clayhanger, 14 Golborne, 14 Clifton, 12 Gore, 11 Clive, 11 Grafton, -

Idirectory&Gazetteer

MORRIS & 00.'8 1 l COMMERCIAL IDIRECTORY &GAZETTEER I . i ,--....-- ~ .~ Ii I I~ OF CHESHIRE. SUBSORIBER'S COPY. HOUNDS GATE, NOTTINGHAM,," I CHE.S"TER I PUBUC I UBRARY f5- JUL 1951 I Re,:: IID/_ ~150 I L.C. J I j PREFACE. .~, L>r submitting this Wark to the Public, the Publishers beg to tender their sincere I. ~ thanks to the nnmerous Subscribers who have honored them with their patronage; 0 -- also to the Clergy, Clerks of the· Peace, Postmasters, Municipal Officers, and other ,1 . Gentlemen who have rendered their Agents valuabJeassislance in the collection J of information. f MORRIS & CO. Nottinglw.m, &ptemher, 1864. I IN D;E X. PAGE . PAGE PAGE Abbotts (Cotton) •••••• 49 Barrow, Little 46 Broxlon 59 Acton-in.Delamere ••• 406 Barlhomley 90 Bruen Stspleford 158 Aeton Grange•••••••••••• 361 Barlington 380 Brnera ;.. 4$ Aeton (Nantwieh) .••••• 33 Barton..................... 62 Budworth, Great 376 Adlington •......••..•••• 251 Basford 113 Budworth, Little 398 Adswood (see Cheadle) 236 Batherton 113 Buerton (Aldford)..... 45 Agden'(Bowdon) •••••• 317 Bebington, Higher! .. 522 Buerton (Audlem)...... 89 Agden (Malp..)......... 58 and Lower Buglawton '132 Alenmlow ••••••.•.•.••.• 149 Beeston 94 Bnlke1ey 59 Alderley •.. .•••••••• 299 Betehton , 124 Bunbury 93 .Alderley Edge ••••••••. 306 Bexton..... 315 Burland 84 Alderley, Nether ...... 299 Biekerton 58 Burloy Dam III Alderley, Over... ••. 300 Biekley 58 Burton(WiiTal)......... 47 Aldersey 50 Bidston-ewn-Ford 491 Burton.by-Tarvin 158 Aldford ••• 44 Birches .. 381 Burwards1ey 94 Allostook : 377 Birkenhesd 429 Butley 255 /' Alpraham •• ,............ 94 Birtles 252 Byley-cum-Yatehouse 416 Alsager 91 Blaekden 123 Caldeeott:........... 66 Altrincham 327 Blaeon-eum-Crabwall 47 Caldy 498 Alvanley 369 Blakenhall 114 Calve1ey 95 ,, Alv..ton 408 Bollin-fee (see Wilms- Capenhurst ,....... -

Remains, Historical & Literary

GENEALOGY COLLECTION Cj^ftljnm ^Ofiftg, ESTABLISHED MDCCCXLIII. FOR THE PUBLICATION OF HISTORICAL AND LITERARY REMAINS CONNECTED WITH THE PALATINE COUNTIES OF LANCASTER AND CHESTEE. patrons. The Right Hon. and Most Rev. The ARCHBISHOP of CANTERURY. His Grace The DUKE of DEVONSHIRE, K.G.' The Rt. Rev. The Lord BISHOP of CHESTER. The Most Noble The MARQUIS of WESTMINSTER, The Rf. Hon. LORD DELAMERE. K.G. The Rt. Hon. LORD DE TABLEY. The Rt. Hon. The EARL of DERBY, K.G. The Rt. Hon. LORD SKELMERSDALE. The Rt. Hon. The EARL of CRAWFORD AND The Rt. Hon. LORD STANLEY of Alderlev. BALCARRES. SIR PHILIP DE M ALPAS GREY EGERTON, The Rt. Hon. LORD STANLEY, M.P. Bart, M.P. The Rt. Rev. The Lord BISHOP of CHICHESTER. GEORGE CORNWALL LEGH, Esq , M,P. The Rt. Rev. The Lord BISHOP of MANCHESTER JOHN WILSON PATTEN, Esq., MP. MISS ATHERTON, Kersall Cell. OTounctl. James Crossley, Esq., F.S.A., President. Rev. F. R. Raines, M.A., F.S.A., Hon. Canon of ^Manchester, Vice-President. William Beamont. Thomas Heywood, F.S.A. The Very Rev. George Hull Bowers, D.D., Dean of W. A. Hulton. Manchester. Rev. John Howard Marsden, B.D., Canon of Man- Rev. John Booker, M.A., F.S.A. Chester, Disney Professor of Classical Antiquities, Rev. Thomas Corser, M.A., F.S.A. Cambridge. John Hakland, F.S.A. Rev. James Raine, M.A. Edward Hawkins, F.R.S., F.S.A., F.L.S. Arthur H. Heywood, Treasurer. William Langton, Hon. Secretary. EULES OF THE CHETHAM SOCIETY. 1.