Foxtel Response to Productivity Commission Draft Report

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

February 26, 2021 Amazon Warehouse Workers In

February 26, 2021 Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer, Alabama are voting to form a union with the Retail, Wholesale and Department Store Union (RWDSU). We are the writers of feature films and television series. All of our work is done under union contracts whether it appears on Amazon Prime, a different streaming service, or a television network. Unions protect workers with essential rights and benefits. Most importantly, a union gives employees a seat at the table to negotiate fair pay, scheduling and more workplace policies. Deadline Amazon accepts unions for entertainment workers, and we believe warehouse workers deserve the same respect in the workplace. We strongly urge all Amazon warehouse workers in Bessemer to VOTE UNION YES. In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (DARE ME) Chris Abbott (LITTLE HOUSE ON THE PRAIRIE; CAGNEY AND LACEY; MAGNUM, PI; HIGH SIERRA SEARCH AND RESCUE; DR. QUINN, MEDICINE WOMAN; LEGACY; DIAGNOSIS, MURDER; BOLD AND THE BEAUTIFUL; YOUNG AND THE RESTLESS) Melanie Abdoun (BLACK MOVIE AWARDS; BET ABFF HONORS) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS; CLOSE ENOUGH; A FUTILE AND STUPID GESTURE; CHILDRENS HOSPITAL; PENGUINS OF MADAGASCAR; LEVERAGE) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; GROWING PAINS; THE HOGAN FAMILY; THE PARKERS) David Abramowitz (HIGHLANDER; MACGYVER; CAGNEY AND LACEY; BUCK JAMES; JAKE AND THE FAT MAN; SPENSER FOR HIRE) Gayle Abrams (FRASIER; GILMORE GIRLS) 1 of 72 Jessica Abrams (WATCH OVER ME; PROFILER; KNOCKING ON DOORS) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEPPER) Nick Adams (NEW GIRL; BOJACK HORSEMAN; -

To Read a PDF Version of This Media Release, Click Here

MEDIA RELEASE 29 July 2020 The past isn’t done with us yet… Catherine Văn-Davies leads the ensemble cast of new Australian drama series Hungry Ghosts Four-night special event on SBS Monday 24 August – Thursday 27 August at 9:30pm • INTERVIEWS AVAILABLE • IMAGES AND SCREENERS: HERE • FIRST LOOK TRAILER: HERE Chilling, captivating and utterly compelling, Hungry Ghosts follows four families that find themselves haunted by ghosts from the past. Filmed and set in Melbourne during the month of the Hungry Ghost Festival, when the Vietnamese community venerate their dead, this four-part drama series event from Matchbox Pictures premieres over four consecutive nights, Monday 24 August – Thursday 27 August at 9:30pm on SBS. When a tomb in Vietnam is accidentally opened on the eve of the Hungry Ghost Festival, a vengeful spirit is unleashed, bringing the dead with him. As these spirits wreak havoc across the Vietnamese-Australian community in Melbourne, reclaiming lost loves and exacting revenge, young woman May Le (Văn-Davies) must rediscover her true heritage and accept her destiny to help bring balance to a community still traumatised by war. Hungry Ghosts reflects the extraordinary lived and spiritual stories of the Vietnamese community and explores the inherent trauma passed down from one generation to the next, and how notions of displacement impact human identity – long after the events themselves. With one of the most diverse casts featured in an Australian drama series, Hungry Ghosts comprises more than 30 Asian-Australian actors and 325 -

Bangalow Farewells Frank Scarrabelotti

THE BYRON SHIRE ECHO Advertising & news enquiries: Mullumbimby 02 6684 1777 Byron Bay 02 6685 5222 Fax 02 6684 1719 [email protected] [email protected] Available early Tuesday at: http://www.echo.net.au VOLUME 22 #02 TUESDAY, JUNE 19, 2007 22,300 copies every week REFILLED EVERY WEEK Bangalow farewells Frank Scarrabelotti Left, Frank Scarrabelotti at the age of 108 in his garden shed. Above, the family farewells Frank at St Kevin’s Church, Bangalow. Photos Jeff Dawson Frank Scarrabelotti, one of Banga- nity into his last decade, from dairy meet the team and wish them good low’s much loved identities, died on farming to rugby union to music. luck. Frank clearly remembered the Tuesday last week at the grand age In his 107th year he and his wife Bangalow team that played in the of 109. Around 300 people turned Nell led the parade for the annual fi nal in 1910, and was able to iden- out for the requiem mass last Fri- Bangalow Billycart Derby, albeit in tify most of the players by name day at St Kevin’s Church, Banga- a car. and the positions they played. low. He was widely regarded as one When Bangalow Rugby Union Ballina MP Don Page paid tribute of life’s true gentlemen. Club played in their fi rst grand to Mr Scarrabelotti in a press release: Born near Coraki on August 4, fi nal since the club was reformed in ‘Frank was highly respected and 1897, Frank was enthusiastically 2003, at the age of 108 Frank came very well liked by all who knew involved in the life of the commu- down to the Bangalow Hotel to continued on page 2 Van Haandels take the reins of iconic Beach Hotel Hans Lovejoy According to current owners ‘The Beach Hotel supported John and Lisa van Haandel’s tor’s future plans are and how it The long anticipated sale and John and Delvene Cornell, they many local good causes as a pub other business interests include will affect the community. -

What Will It Take to Save Comedy Central?

What Will it Take to Save Comedy Central? 08.16.2016 Comedy Central's cancellation of The Nightly Show is the latest in a series of signals that all is not well at the network that was once the home of the country's sharpest political satire and news commentary. On Monday, Comedy Central announced that it was cancelling the show, which took Stephen Colbert's Colbert Report time slot in February 2015 when Colbert moved over to CBS' The Late Show. The move was not surprising considering the ratings: The Nightly Show is averaging a barely-there 0.2 among its key demographic of adults 18-49. RELATED: Comedy Central Cancels 'The Nightly Show' But The Nightly Show's failure to catch on is not the only problem at Comedy Central. Consider its late-night partner, The Daily Show, long the network's marquee program with host Jon Stewart. Stewart left the show just over a year ago and was replaced with South African comic Trevor Noah, who was hand-picked by Stewart. But despite Comedy Central's best efforts to reassure the media and audiences that Noah would eventually catch on, so far he hasn't. In May, The Wrap reported that The Daily Show had lost 38% of Stewart's audience among millennials aged 18-34 and 35% in households. And that comes at a time when the country is in the middle of a presidential election that lends itself extremely well to satire. It's also proven to be a mistake to let so much of its talent walk out the door, with Stephen Colbert going to CBS, John Oliver to HBO and Samantha Bee to TBS, taking much of Comedy Central's brand equity with them. -

Streaming Yujin Luo Final

The Streaming War During the Covid-19 Pandemic Yujin Luo The Streaming War During the Covid-19 Pandemic 2 home, which is the ideal condition for The Covid-19 pandemic has drastically binge-watching. disrupted all business sectors. The arts, culture, and entertainment industries have To understand how the pandemic is shaping been hit exceptionally hard since the virus’ the streaming industry, it is important to first outbreak in January. In response to the understand its pre-Covid and current status. crisis, businesses have taken immediate The following analysis will divide the actions: transitioning to remote work, timeline into before 2020 and in 2020 based canceling and postponing live events on Covid-19’s first outbreak in January nationwide, shutting down entertainment 2020. venues, etc., resulting in lost revenues from sales, merchandising, advertising, and The Streaming Industry’s Pre-Covid promotions. Unfortunately, the Covid-19 State of the Major Players in the pandemic’s impacts are far more Streaming War permanent for an audience-oriented industry that requires a high level of Early adopters and fast followers used to be engagement. The business model might be the main audiences of streaming services, fundamentally changed and there will or in other words, streaming used to be a certainly be a shift in how content is niche add-on to traditional TV. Now, it is produced and consumed. transitioning to a new stage as a mainstream element in the entertainment While lockdowns and social distancing industry. The major streaming services from measures to contain the pandemic have before Covid are shown in the table below, had a huge impact on the traditional movie except for HBO Max, Peacock, and Quibi industry, the video streaming model seems (RIP) that just launched in 2020. -

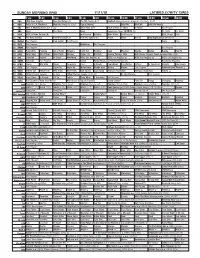

Sunday Morning Grid 11/11/18 Latimes.Com/Tv Times

SUNDAY MORNING GRID 11/11/18 LATIMES.COM/TV TIMES 7 am 7:30 8 am 8:30 9 am 9:30 10 am 10:30 11 am 11:30 12 pm 12:30 2 CBS CBS News Sunday Face the Nation (N) The NFL Today (N) Å Football Arizona Cardinals at Kansas City Chiefs. (N) Å 4 NBC Today in L.A. Weekend Meet the Press (N) (TVG) Figure Skating NASCAR NASCAR NASCAR Racing 5 CW KTLA 5 Morning News at 7 (N) Å KTLA News at 9 KTLA 5 News at 10am In Touch Paid Program 7 ABC News This Week News Eyewitness News 10:00AM (N) Dr. Scott Dr. Scott 9 KCAL KCAL 9 News Sunday (N) Joel Osteen Schuller Mike Webb Paid Program REAL-Diego Paid 1 1 FOX Fox News Sunday FOX NFL Kickoff (N) FOX NFL Sunday (N) Planet Weird DIY Sci They Fight (2018) (Premiere) 1 3 MyNet Paid Program Fred Jordan Paid Program News Paid 1 8 KSCI Paid Program Buddhism Paid Program 2 2 KWHY Paid Program Paid Program 2 4 KVCR Paint With Painting Joy of Paint Wyland’s Paint This Painting Cook Mexican Martha Belton Baking How To 2 8 KCET Zula Patrol Zula Patrol Mixed Nutz Edisons Curios -ity Biz Kid$ Forever Painless With Rick Steves’ Europe: Great German Cities (TVG) 3 0 ION Jeremiah Youseff In Touch Ankerberg NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å NCIS: Los Angeles Å 3 4 KMEX Conexión Paid Program Fútbol Fútbol Mexicano Primera División (N) República Deportiva 4 0 KTBN James Win Walk Prince Carpenter Jesse In Touch PowerPoint It is Written Jeffress K. -

The Donald Trump-Rupert Murdoch Relationship in the United States

The Donald Trump-Rupert Murdoch relationship in the United States When Donald Trump ran as a candidate for the Republican presidential nomination, Rupert Murdoch was reported to be initially opposed to him, so the Wall Street Journal and the New York Post were too.1 However, Roger Ailes and Murdoch fell out because Ailes wanted to give more positive coverage to Trump on Fox News.2 Soon afterwards, however, Fox News turned more negative towards Trump.3 As Trump emerged as the inevitable winner of the race for the nomination, Murdoch’s attitude towards Trump appeared to shift, as did his US news outlets.4 Once Trump became the nominee, he and Rupert Murdoch effectively concluded an alliance of mutual benefit: Murdoch’s news outlets would help get Trump elected, and then Trump would use his powers as president in ways that supported Rupert Murdoch’s interests. An early signal of this coming together was Trump’s public attacks on the AT&T-Time Warner merger, 21st Century Fox having tried but failed to acquire Time Warner previously in 2014. Over the last year and a half, Fox News has been the major TV news supporter of Donald Trump. Its coverage has displayed extreme bias in his favour, offering fawning coverage of his actions and downplaying or rubbishing news stories damaging to him, while also leading attacks against Donald Trump’s opponent in the 2016 presidential election, Hillary Clinton. Ofcom itself ruled that several Sean Hannity programmes in August 2016 were so biased in favour of Donald Trump and against Hillary Clinton that they breached UK impartiality rules.5 During this period, Rupert Murdoch has been CEO of Fox News, in which position he is also 1 See e.g. -

Ofve' NEW RESIDENTIALCHANNEL LINEUP Effective 2/1 6/16

Odessa, TX CABLEOfVE' NEW RESIDENTIALCHANNEL LINEUP Effective 2/1 6/16 ECONOMY STAN DARD/ D I G ITAL VALU E PACK* xDigital Standard Cable includes Economy. Value Pack Channels noted in yellow. Additional fee applies. 3 455 ABC.KMID Women's Programming Fomily Programming "too7 .ll 'r,t'¡., I 7 cBs-KosA 1260 Animal Planet 100 1 100 Lifetime 260 B 475 FOX-KPEJ 1262 National Geographic Wild 102 1 102 LMN 262 9 1 009 NBC.KWES 103 OWN 263 1263 Discovery Channel Channel 13 1013 PB5-KPBT "t04 1 104 Bravo 26s 1265 Science Channel 16 1016 MyNetwork-KOSA 108 WE 266 1266 Hallmark 268 1264 Hallmark Movies & Mysteries 17 CW-KWES 112 lnvestigation DiscoverY 114 Oxygen 270 1270 Food Network 1B 1018 Univision-KUPB 1"16 Discovery Life 272 1272 HGTV 20 Telemundo-KTLE 274 1274 History Channel 2',! Galavision Sports 276 1276 H2 (Viceland) 22 UniMas 133 1 133 ESPN 277 1277 National Geographic Ch. '134 "t134 25 MeTV-KWWT ESPN2 241 Travel Channel 135 ESPN News 26 Decades 136 ESPNU Ch il dren's Proqra m m i n q 27 Movies 1 NBC Sports 137 137 300 1 300 Sprout 52 God's Learning Channel-KMLM "t39 ',t39 1 CBS Sports 302 1302 Disney Channel 56 Goverment Access 140 FCS Atlantic 304 Disney XD '141 72 Leased Access FCS Central 307 1307 FreeForm FCS Pacific 7B C-SPAN 142 311 Discovery Family 146 1146 FOX Sports 1 79 C-SPAN2 313 Disney Jr. 144 1 144 FOX Sports 2 Boomerang BO BYU 316 1 FOX Sports SW 155 155 317 1317 Cartoon Network 82 INSP 157 1157 NFL Network TBN 1 Golf Channel B4 158 158 News 85 EWTN 160 1 160 Outdoor €hannel 333 TheWeather Channel 161 ESPN Classic B6 -

Ellie Smith 1St Assistant Director

ELLIE SMITH 1ST ASSISTANT DIRECTOR TELEVISION A LEAGUE OF THEIR OWN (Pilot) Sony/Amazon Prod: Abbi Jacobson, Will Graham, Michael Cedar Dir: Jamie Babbit THE STRANGER (Limited series) Fox 21 TV/Quibi Prod: Veena Sud, Jeffrey Katzenberg Dir: Veena Sud LIGHT AS A FEATHER (Season 2) Hulu/Awesomeness TV Prod: Brin Lukens, Dylan Vox Dir: Alexis Ostrander PEARSON (Season 1) UCP/USA Prod: Daniel Arkin, David Bartis, Aaron Korsh, Dir: Anton Cropper Doug Liman, Gina Torres LESS THAN ZERO (Pilot) Fox 21/Hulu Prod: Craig Wright, Rebecca Sinclair, Bob Williams Dir: Brett Morgen FOURSOME (Season 4) Awesomeness TV/ Prod: Lance Lanfear, Dan Suhart Dir: Various YouTube Red THE CHI (Season 1) Fox 21 TV/Showtime Prod: Elwood Reid, Lena Waithe, Common, Aaron Kaplan Dir: Various *Nominated – Television – Peabody Awards, 2019 IDIOTSITTER (Season 2) Comedy Central Prod: Jillian Bell, Charlotte Newhouse, Dan Kuba Dir: Various GRAVES (Promo) Lionsgate TV/EPIX Prod: Joshua Michael Stern Dir: Larry Charles THE CATCH (Season 1) (2nd Unit) ABC Studios/ABC Prod: Shonda Rhimes, Kevin Dowling Dir: Various DOPE GIRLS (Pilot) MTV Prod: Harry Elfont, Deborah Kaplan, Ken Ornstein Dir: Michael Blieden SIRENS (Seasons 1 & 2) Fox 21 TV/USA Prod: Denis Leary, Jim Serpico, Tom Sellitti Dir: Various CHICAGO FIRE (Season 1) (2nd AD) Universal TV/NBC Prod: Dick Wolf, Joe Chappelle, John L. Roman Dir: Various NCIS-LA (Seasons 1 & 2) CBS TV/CBS Prod: Shane Brennan Dir: Various HEROES (Seasons 1 & 2) (2nd AD) Universal TV/NBC Prod: Tim Kring Dir: Various LAST MYSTERIES OF TITANIC -

Subscription TV Homes Only Week 10 2019 (03/03/2019 - 09/03/2019) 18:00 - 23:59 Total Individuals - Including Guests

Consolidated National Subscription TV Share and Reach National Share and Reach Report - Subscription TV Homes only Week 10 2019 (03/03/2019 - 09/03/2019) 18:00 - 23:59 Total Individuals - Including Guests Channel Share Of Viewing Reach Weekly 000's % TOTAL PEOPLE ABC 5.8 1900 ABCKIDS/COMEDY 1.0 714 ABC ME 0.2 259 ABC NEWS 0.5 480 Seven + AFFILIATES 14.5 3056 7TWO + AFFILIATES 0.8 522 7mate + AFFILIATES 1.3 893 7flix + AFFILIATES 0.4 385 7food network + AFFILIATES 0.2 125 Nine + AFFILIATES* 16.8 3432 GO + AFFILIATES* 1.8 1100 Gem + AFFILIATES* 0.7 478 9Life + AFFILIATES* 0.7 482 10 + AFFILIATES* 7.5 2745 10 Bold + AFFILIATES* 0.7 607 10 Peach + AFFILIATES* 0.9 823 Sky News on WIN + AFFILIATES* 0.2 225 SBS 2.0 1398 SBS VICELAND 0.5 726 SBS Food 0.5 465 NITV 0.1 189 111 0.7 559 111 +2 0.2 242 13TH STREET 0.9 398 13TH STREET+2 0.2 139 [V] 0.1 187 [V] +2 0.0 122 A&E 0.6 451 A&E+2 0.3 232 Animal Planet 0.2 224 ARENA 0.7 532 ARENA+2 0.2 188 BBC First 0.8 505 BBC Knowledge 0.4 324 beIN SPORTS 1 0.0 55 beIN SPORTS 2 0.0 72 beIN SPORTS 3 0.1 115 Binge 0.1 201 Boomerang 0.1 85 BoxSets 1.5 450 Cartoon Network 0.2 146 CBeebies 0.1 89 COMEDY CHANNEL 0.4 451 COMEDY CHANNEL+2 0.2 205 Country Music Channel 0.0 64 crime + investigation 1.2 514 Discovery Channel 0.7 607 Discovery Channel+2 0.2 293 Discovery Kids 0.0 30 Discovery Science 0.3 246 Discovery Turbo 0.3 229 Excludes Tasmania *Affiliation changes commenced July 1, 2016. -

As Writers of Film and Television and Members of the Writers Guild Of

July 20, 2021 As writers of film and television and members of the Writers Guild of America, East and Writers Guild of America West, we understand the critical importance of a union contract. We are proud to stand in support of the editorial staff at MSNBC who have chosen to organize with the Writers Guild of America, East. We welcome you to the Guild and the labor movement. We encourage everyone to vote YES in the upcoming election so you can get to the bargaining table to have a say in your future. We work in scripted television and film, including many projects produced by NBC Universal. Through our union membership we have been able to negotiate fair compensation, excellent benefits, and basic fairness at work—all of which are enshrined in our union contract. We are ready to support you in your effort to do the same. We’re all in this together. Vote Union YES! In solidarity and support, Megan Abbott (THE DEUCE) John Aboud (HOME ECONOMICS) Daniel Abraham (THE EXPANSE) David Abramowitz (CAGNEY AND LACEY; HIGHLANDER; DAUGHTER OF THE STREETS) Jay Abramowitz (FULL HOUSE; MR. BELVEDERE; THE PARKERS) Gayle Abrams (FASIER; GILMORE GIRLS; 8 SIMPLE RULES) Kristen Acimovic (THE OPPOSITION WITH JORDAN KLEEPER) Peter Ackerman (THINGS YOU SHOULDN'T SAY PAST MIDNIGHT; ICE AGE; THE AMERICANS) Joan Ackermann (ARLISS) 1 Ilunga Adell (SANFORD & SON; WATCH YOUR MOUTH; MY BROTHER & ME) Dayo Adesokan (SUPERSTORE; YOUNG & HUNGRY; DOWNWARD DOG) Jonathan Adler (THE TONIGHT SHOW STARRING JIMMY FALLON) Erik Agard (THE CHASE) Zaike Airey (SWEET TOOTH) Rory Albanese (THE DAILY SHOW WITH JON STEWART; THE NIGHTLY SHOW WITH LARRY WILMORE) Chris Albers (LATE NIGHT WITH CONAN O'BRIEN; BORGIA) Lisa Albert (MAD MEN; HALT AND CATCH FIRE; UNREAL) Jerome Albrecht (THE LOVE BOAT) Georgianna Aldaco (MIRACLE WORKERS) Robert Alden (STREETWALKIN') Richard Alfieri (SIX DANCE LESSONS IN SIX WEEKS) Stephanie Allain (DEAR WHITE PEOPLE) A.C. -

2020 Full Year Results Announcement

27 August 2020 ASX Markets Announcement Office ASX Limited 20 Bridge Street Sydney NSW 2000 2020 FULL YEAR RESULTS ANNOUNCEMENT Attached is a copy of the ASX release relating to the 2020 Full Year Financial Results for Nine Entertainment Co. Holdings Limited Rachel Launders Company Secretary Authorised for release: Nine Board sub-committee Further information: Nola Hodgson Victoria Buchan Head of Investor Relations Director of Communications +61 2 9965 2306 +61 2 9965 2296 [email protected] [email protected] nineforbrands.com.au Nine Sydney - 1 Denison Street, North Sydney, NSW, 2068 ABN 60 122 203 892 NINE ENTERTAINMENT CO. FY20 FINAL RESULTS 27 August 2020: Nine Entertainment Co. (ASX: NEC) has released its FY20 results for the 12 months to June 2020. On a Statutory basis, Nine reported Revenue of $2.2b and a Net Loss of $575m, which included a post-tax Specific Item cost of $665m, largely relating to impairment of goodwill. On a pre AASB16 and Specific Item basis, Nine reported Group EBITDA of $355m, down 16% on the Pro Forma results in FY19 for its Continuing Businesses. On the same basis, Net Profit After Tax and Minority Interests was $160m, down 19%. Key takeaways include: • Audience growth across all key platforms – Metro Publishing, Stan, 9Now, Radio and FTA • Strong growth from digital video businesses o $51m EBITDA improvement at Stan1, with current active subscribers of 2.2m o 36% EBITDA growth at 9Now1 to $49m, with market leading BVOD revenue share of ~50% • Ad markets heavily impacted by COVID-19 from March 2020 • Nine was quick to mitigate the associated fallout with o $225m cost-out program – cash basis, CY20 o Including increasing and expediting previous cost initiatives • 40% growth in digital EBITDA to $166m ($178m post AASB16) • Evolution of Metro Media business to consumer focus, with reader revenue now accounting for almost 60% of total revenue • Strong balance sheet, with (wholly-owned) leverage ratio <1X 1 like-basis, pre AASB16 Hugh Marks, Chief Executive Officer of Nine Entertainment Co.