Native Forest Birds of Guam and Rota of the Commonwealth of the Norther1~ Mariana Islands Recovery Plan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dietary Behavior of the Mangrove Monitor Lizard (Varanus Indicus)

DIETARY BEHAVIOR OF THE MANGROVE MONITOR LIZARD (VARANUS INDICUS) ON COCOS ISLAND, GUAM, AND STRATEGIES FOR VARANUS INDICUS ERADICATION A THESIS SUBMITTED TO THE GRADUATE DIVISION OF THE UNIVERSITY OF HAWAI’I AT HILO IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF SCIENCE IN TROPICAL CONSERVATION BIOLOGY AND ENVIRONMENTAL SCIENCE MAY 2016 By Seamus P. Ehrhard Thesis Committee: William Mautz, Chairperson Donald Price Patrick Hart Acknowledgements I would like to thank Guam’s Department of Agriculture, the Division of Aquatic and Wildlife Resources, and wildlife biologist, Diane Vice, for financial assistance, research materials, and for offering me additional staffing, which greatly aided my fieldwork on Guam. Additionally, I would like to thank Dr. William Mautz for his consistent help and effort, which exceeded all expectations of an advisor, and without which I surely would have not completed my research or been inspired to follow my passion of herpetology to the near ends of the earth. 2 Abstract The mangrove monitor lizard (Varanus indicus), a large invasive predator, can be found on all areas of the 38.6 ha Cocos Island at an estimated density, in October 2011, of 6 V. Indicus per hectare on the island. Plans for the release of the endangered Guam rail (Gallirallus owstoni) on Cocos Island required the culling of V. Indicus, because the lizards are known to consume birds and bird eggs. Cocos Island has 7 different habitats; resort/horticulture, Casuarina forest, mixed strand forest, Pemphis scrub, Scaevola scrub, sand/open area, and wetlands. I removed as many V. Indicus as possible from the three principal habitats; Casuarina forest, mixed scrub forest, and a garbage dump (resort/horticulture) using six different trapping methods. -

NOTE Dimensions and Composition of Mariana Crow Nests on Rota

Micronesica 29(2): 299- 304, 1996 NOTE Dimensionsand Compositionof Mariana Crow Nests on Rota, Mariana Islands MICHAEL R. LUSK 1 AND ESTANISLAO TAISACAN Division of Fish and Wildlife, Rota, MP 96951. Abstract-From 1992 to 1994 we measured dimensions of 11 Mariana crow (Corvus kubaryz) nests on Rota. The mean nest diameter, nest height, inner cup diameter, and cup depth were 37.2 cm, 15.4 cm, 13.3 cm, and 6.9 cm, respectively. These nests consisted of an outer platform and intermediate cup primarily composed Jasminum marianum, and an inner cup mainly of Cocos nucifera frond fibers and Ficus prolixa root lets. The platforms of two nests contained an average of 200 twigs, with most being 2.1-4.0 mm in diameter and 201-250 mm long. The inter mediate cups averaged 93 components, with most twigs measuring 0.0- 2.0 mm in diameter and 101-150 mm long. Total weight of the two nests averaged 347.5 g, with the following breakdown: platform 284.1 g, in termediate cup 42.1 g, and inner cup 21.3 g. Introduction The Mariana crow ( Corvus kubaryz) is the only corvid in Micronesia and occurs only in forested habitats on two islands in the Marianas, Guam and Rota. It was listed as endangered by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service in 1984 (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service 1984). Although basic information is lacking on all aspects of the life history of the Mariana crow, Jenkins (1983), Tomback (1986), and Michael (1987) describe in varying detail Mariana crow nest construction on Guam and Rota. -

Revised Recovery Plan for the Sihek Or Guam Micronesian Kingfisher (Halcyon Cinnamomina Cinnamomina)

DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate actions which the best available science indicates are required to recover and protect listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and sometimes prepared with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and others. Recovery teams serve as independent advisors to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Recovery plans are reviewed by the public and submitted to additional peer review before they are approved and adopted by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Nothing in this plan should be construed as a commitment or requirement that any Federal agency obligate or pay funds in contravention of the Anti-Deficiency Act, 31 USC 1341, or any other law or regulation. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Recovery plans represent the official position of the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service only after they have been signed as approved by the Regional Director or Director. Approved recovery plans are subject to modification as dictated by new findings, changes in species status, and the completion of recovery actions. Please check for updates or revisions at the website addresses provided below before using this plan. Literature citation of this document should read as follows: U.S. -

The Challenges Surrounding Reintroduction Biology

The Challenges Surrounding Reintroduction Biology BY KATIE MORELL 22 www.aza.org | January 2016 January 2016 | www.aza.org 23 Listed as extinct in the wild by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN), the bird has yet to be reintroduced to its native land, so a satellite home for the species has been created on the neighboring Pacific island of Rota— the place where Newland felt his faith in reintroduction falter, if just for a minute. “On my first trip to Rota, I remember stepping off the plane and seeing a rail dead on the ground at the airport,” he said. “Someone had run over it with their car.” The process of reintroducing a species into the wild can be tricky at best. There are hundreds of factors that go into the decision—environmental, political and © Sedgwick County Zoo, Yang Zhao Yang Zoo, © Sedgwick County sociological. When it works, the results are exhilarating for the public and environmentalists. That is what happened in the 1980s when biologists were alerted to the plight of the California condor, pushed to near extinction by a pesticide called DDT. By 1982, there were only 23 condors left; five years later, a robust breeding and reintroduction program was initiated to save the species. The program worked, condors were released, DDT was outlawed and, according to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS), as of 2008 there were t was a few years ago when Scott more condors flying in the wild than in Newland felt his heart drop to managed care. his feet. -

TRANSACTIONS of the Fifty-Seventh North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference

TRANSACTIONS of the Fifty-seventh North American Wildlife and Natural Resources Conference Conference theme— Crossroads of Conservation: 500 Years After Columbus Marc/, 27-Apr;V 7. 7992 Radisson Plaza Hotel Charlotte and Charlotte Convention Center Charlotte, North Carolina Edited by Richard E. McCabe i w Published by the Wildlife Management Institute, Washington, DC, 1992 Johnson, M. L. and M, S. Gaines. 1988. Demography of the western harvest mouse, Reithrodon- Managing Genetic Diversity in Captive Breeding tomys megalotis, in eastern Kansas. Oecologia 75:405-411. Kareiva, P. and M, Anderson. 1988. Spatial aspects of .species interactions'. The wedding of models and Reproduction Programs and experiments. In A. Hasting, ed., Community Ecology. Springer-Verlag. New York, NY. Lande, R. 1988. Genetics and demography in biological conservation. Science 241; 1,455-1,460. Levins, R. A. 1980. Extinction. Am. Mathematical Soc. 2:77-107... Katherine Rails and Jonathan D. Ballon Lovejoy, T. B. 1985. Forest fragmentation in the Amazon: A case study. Pages 243-252 in H. Department of Zoological Research Messel, ed., The Study of Populations. Pergamon Press, Sydney, Australia. National Zoological Park Lovejoy, T. E., J. M. Rankin, R. O. Bierregaard, K. S. Brown, L. H. Emmons, and M. E. Van Smithsonian Institution der Voort. 1984. Ecosystem decay of Amazon Forest fragments. Pages 295-325 in M. H. Washington, D.C. Nitecki, ed., Extinctions. Univ. Chicago Press. Chicago, IL. Lovejoy, T. E., R. O. Bierregaard, Jr., A. B. Rylands, J. R. Malcolm, C. E. Quintela, L. H. Harper, K. S. Brown, Jr., A. H. Powell, G. V. N. Powell, H. 0, R. -

Genetic Applications in Avian Conservation

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln USGS Staff -- Published Research US Geological Survey 2011 Genetic Applications in Avian Conservation Susan M. Haig U.S. Geological Survey, [email protected] Whitcomb M. Bronaugh Oregon State University Rachel S. Crowhurst Oregon State University Jesse D'Elia U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Collin A. Eagles-Smith U.S. Geological Survey See next page for additional authors Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub Haig, Susan M.; Bronaugh, Whitcomb M.; Crowhurst, Rachel S.; D'Elia, Jesse; Eagles-Smith, Collin A.; Epps, Clinton W.; Knaus, Brian; Miller, Mark P.; Moses, Michael L.; Oyler-McCance, Sara; Robinson, W. Douglas; and Sidlauskas, Brian, "Genetic Applications in Avian Conservation" (2011). USGS Staff -- Published Research. 668. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usgsstaffpub/668 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the US Geological Survey at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in USGS Staff -- Published Research by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Authors Susan M. Haig, Whitcomb M. Bronaugh, Rachel S. Crowhurst, Jesse D'Elia, Collin A. Eagles-Smith, Clinton W. Epps, Brian Knaus, Mark P. Miller, Michael L. Moses, Sara Oyler-McCance, W. Douglas Robinson, and Brian Sidlauskas This article is available at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/ usgsstaffpub/668 The Auk 128(2):205–229, 2011 The American Ornithologists’ Union, 2011. Printed in USA. SPECIAL REVIEWS IN ORNITHOLOGY GENETIC APPLICATIONS IN AVIAN CONSERVATION SUSAN M. HAIG,1,6 WHITCOMB M. BRONAUGH,2 RACHEL S. -

![Docket No. FWS–HQ–MB–2018–0047; FXMB 12320900000//201//FF09M29000]](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/7074/docket-no-fws-hq-mb-2018-0047-fxmb-12320900000-201-ff09m29000-1487074.webp)

Docket No. FWS–HQ–MB–2018–0047; FXMB 12320900000//201//FF09M29000]

This document is scheduled to be published in the Federal Register on 04/16/2020 and available online at federalregister.gov/d/2020-06779, and on govinfo.gov Billing Code 4333–15 DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR Fish and Wildlife Service 50 CFR Part 10 [Docket No. FWS–HQ–MB–2018–0047; FXMB 12320900000//201//FF09M29000] RIN 1018–BC67 General Provisions; Revised List of Migratory Birds AGENCY: Fish and Wildlife Service, Interior. ACTION: Final rule. SUMMARY: We, the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (Service), revise the List of Migratory Birds protected by the Migratory Bird Treaty Act (MBTA) by both adding and removing species. Reasons for the changes to the list include adding species based on new taxonomy and new evidence of natural occurrence in the United States or U.S. territories, removing species no longer known to occur within the United States or U.S. territories, and changing names to conform to accepted use. The net increase of 67 species (75 added and 8 removed) will bring the total number of species protected by the MBTA to 1,093. We regulate the taking, possession, transportation, sale, purchase, barter, exportation, and importation of migratory birds. An accurate and up-to-date list of species protected by the MBTA is essential for public notification and regulatory purposes. DATES: This rule is effective [INSERT DATE 30 DAYS AFTER DATE OF PUBLICATION IN THE FEDERAL REGISTER]. 1 FOR FURTHER INFORMATION CONTACT: Eric L. Kershner, Chief of the Branch of Conservation, Permits, and Regulations; Division of Migratory Bird Management; U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service; MS: MB; 5275 Leesburg Pike, Falls Church, VA 22041-3803; (703) 358-2376. -

Guam Rail Conservation: a Milestone 30 Years in the Making by Kurt Hundgen, Director of Animal Collections

CONSERVATION & RESEARCH UPDATES FROM THE NATIONAL AVIARY SPRING 2021 Guam Rail Conservation: A Milestone 30 Years in the Making by Kurt Hundgen, Director of Animal Collections t the end of 2019 the conservation Working together through the Guam best of all, recent sightings of unbanded world celebrated a momentous Rail Species Survival Plan® (SSP), some rails there confirm that the species has achievement:A Guam Rail, once ‘Extinct twenty zoos strategized ways to ensure the already successfully reproduced in the in the Wild,’ was elevated to ‘Critically genetic diversity and health of this small wild for the first time in almost 40 years. Endangered’ status thanks to the recent population of Guam Rails in human care. The international collaboration that successful reintroduction of the species Their goal was to increase the size of the made the success of the Guam Rail to the wild. This conservation milestone zoo population and eventually introduce reintroduction possible likely will go is more than thirty years in the making— the species onto islands near Guam that down in conservation history. Behind the hoped-for result of intensive remained free of Brown Tree Snakes. every ko’ko’ once again living in the collaboration among multiple zoos and Guam wildlife officials have slowly wild is the very successful collaboration government agencies separated by oceans returned Guam Rails to the wild on the among many organizations and hundreds and continents. It is an extremely rare small neighboring islands of Cocos and of dedicated conservationists. conservation success story, shared by Rota. Reintroduction programs are most And we hope that there will be only one other bird: the iconic successful when local governments and California Condor. -

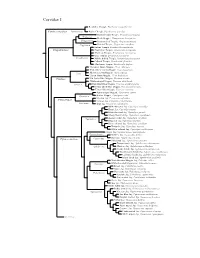

Corvidae Species Tree

Corvidae I Red-billed Chough, Pyrrhocorax pyrrhocorax Pyrrhocoracinae =Pyrrhocorax Alpine Chough, Pyrrhocorax graculus Ratchet-tailed Treepie, Temnurus temnurus Temnurus Black Magpie, Platysmurus leucopterus Platysmurus Racket-tailed Treepie, Crypsirina temia Crypsirina Hooded Treepie, Crypsirina cucullata Rufous Treepie, Dendrocitta vagabunda Crypsirininae ?Sumatran Treepie, Dendrocitta occipitalis ?Bornean Treepie, Dendrocitta cinerascens Gray Treepie, Dendrocitta formosae Dendrocitta ?White-bellied Treepie, Dendrocitta leucogastra Collared Treepie, Dendrocitta frontalis ?Andaman Treepie, Dendrocitta bayleii ?Common Green-Magpie, Cissa chinensis ?Indochinese Green-Magpie, Cissa hypoleuca Cissa ?Bornean Green-Magpie, Cissa jefferyi ?Javan Green-Magpie, Cissa thalassina Cissinae ?Sri Lanka Blue-Magpie, Urocissa ornata ?White-winged Magpie, Urocissa whiteheadi Urocissa Red-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa erythroryncha Yellow-billed Blue-Magpie, Urocissa flavirostris Taiwan Blue-Magpie, Urocissa caerulea Azure-winged Magpie, Cyanopica cyanus Cyanopica Iberian Magpie, Cyanopica cooki Siberian Jay, Perisoreus infaustus Perisoreinae Sichuan Jay, Perisoreus internigrans Perisoreus Gray Jay, Perisoreus canadensis White-throated Jay, Cyanolyca mirabilis Dwarf Jay, Cyanolyca nanus Black-throated Jay, Cyanolyca pumilo Silvery-throated Jay, Cyanolyca argentigula Cyanolyca Azure-hooded Jay, Cyanolyca cucullata Beautiful Jay, Cyanolyca pulchra Black-collared Jay, Cyanolyca armillata Turquoise Jay, Cyanolyca turcosa White-collared Jay, Cyanolyca viridicyanus -

I OFFICE of the LEGISLATIVE SECRETARY ( the Honorable Joanne M

CARL T.C. GUTIERREZ GOVERNOR OF GUAM I JUL 1 1 ZNfl I OFFICE OF THE LEGISLATIVE SECRETARY ( The Honorable Joanne M. S. Brown Legislative Secretary I Mina'Bente Singko na Liheslaturan Twenty-Fifth Guam Legislature Suite 200 130 Aspinal Street ~a~iltf&Guam 96910 Dear Legislative Secretary Brown: Enclosed please find Substitute Bill No. 427 (COR), "AN ACT TO REPEAL AND REENACT $1023 OF CHAPTER 10 OF TITLE 1 OF THE GUAM CODE ANNOTATED, RELATIVE TO THE DESIGNATION OF THE OFFICIAL BIRD OF GUAM, which was signed into law Public Law No. 25-155. This legislation changes the officid bird of Guam from the Totot, the Mariana Fruit Dove (Ptilinoppus roseicapilla), to the Ko'ko, the Guam Rail (Gallirallus owstoni). The idea for this change was generated by the Guam Department of Agriculture, which has been involved for a number of years in the effort to preserve and protect the Ko'ko. In fact, the Department of Agriculture had a number of village meetings to determine community feeling, and then their draft legislation was forwarded to the Legislature by the Administration. The Ko'ko has already become something of a symbol for Guam, and was used as a mascot during the South Pacific Games held here last year. I only to Guam, while the Totot is indigenous not only to Guam but also This fact, along with the concentrated local effort to preserve the Ko'ko that effort is now achieving, make it especially appropriate to have official bird of Guam. A portion of Andersen Air Force Base is set free" zone to provide undisturbed habitat to the Ko'ko, and birds and reproducing in the area The Department of Agriculture is habitat area. -

Boiga Irregularis (Brown Tree Snakes) on Guam and Its Effect on Fauna

Boiga irregularis (Brown Tree Snakes) on Guam and Its Effect on Fauna Alexandria Amand Introduction The island of Guam, a U. S. Territory, is located in the tropical western Pacific, nearly equidistant from Japan to the north, the Philippines to the west, and New Guinea to the South (Enbring & Ftitts 1988). The island is longer than it is wide and is divided into a diverse landscape with forests and cliffs in the north and primarily savannas and river valleys in the south (Savidge 1987). Guam is also a land of great biodiversity including small mammals, reptiles, and numerous bird species; however, snakes are not a natural part of this biodiversity. The burrowing blind snake (Rhamphotyphlops braminus), the only native snake to Guam, does not pose a threat to the fauna, yet the introduction of Boiga irregularis (brown tree snake) has threatened the island’s biodiversity. Boiga irregularis a native to Indonesia, New Guinea, Solomon Islands, and Australia, was introduced to Guam by way of navy vessels shortly after World War II where it is an exotic and invasive species (Butler 1997). As a result of its accidental introduction and population explosion, Boiga irregularis is responsible for a loss of biodiversity through predation. Boiga irregualris has had devastating effects particularly on avifauna such as the Guam rail and Guam flycatcher, small mammals including the Mariana fruit bat, and reptiles such as geckos and skinks. This paper will outline the negative impact that Boiga irregularis has had on the biodiversity of Guam, as well as the techniques being used to control the snakes population and discuss their effectiveness. -

DRAFT REVISED RECOVERY PLAN for the SIHEK OR GUAM MICRONESIAN KINGFISHER (Halcyon Cinnamomina Cinnamomina)

Cover photo of #26, the last remaining wild-born Guam Micronesian kingfisher. Courtesy of the Chicago Zoological Society/Photo by Jim Schulz, used with permission. DRAFT REVISED RECOVERY PLAN FOR THE SIHEK OR GUAM MICRONESIAN KINGFISHER (Halcyon cinnamomina cinnamomina) (March 2004) Original plan approved: September 28, 1990 (Native Forest Birds of Guam and Rota of the Commonwealth of the Northern Mariana Islands) Region 1 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Portland, Oregon Approved: XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX Regional Director, U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Date: XXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXXX DISCLAIMER Recovery plans delineate actions which the best available science indicates are required to recover and protect listed species. Plans are published by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and sometimes prepared with the assistance of recovery teams, contractors, State agencies, and others. Recovery teams serve as independent advisors to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Recovery plans are reviewed by the public and submitted to additional peer review before they are approved and adopted by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. Objectives will be attained and any necessary funds made available subject to budgetary and other constraints affecting the parties involved, as well as the need to address other priorities. Nothing in this plan should be construed as a commitment or requirement that any Federal agency obligate or pay funds in contravention of the Anti-Deficiency Act, 31 USC 1341, or any other law or regulation. Recovery plans do not necessarily represent the views nor the official positions or approval of any individuals or agencies involved in the plan formulation, other than the U.S.