Cleft Palate Speech and Feeding Train the Trainer Module 3.1: ● Oral Examination ● Speech Sound Assessment

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Origin of the Peculiarities of the Vietnamese Alphabet André-Georges Haudricourt

The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet André-Georges Haudricourt To cite this version: André-Georges Haudricourt. The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet. Mon-Khmer Studies, 2010, 39, pp.89-104. halshs-00918824v2 HAL Id: halshs-00918824 https://halshs.archives-ouvertes.fr/halshs-00918824v2 Submitted on 17 Dec 2013 HAL is a multi-disciplinary open access L’archive ouverte pluridisciplinaire HAL, est archive for the deposit and dissemination of sci- destinée au dépôt et à la diffusion de documents entific research documents, whether they are pub- scientifiques de niveau recherche, publiés ou non, lished or not. The documents may come from émanant des établissements d’enseignement et de teaching and research institutions in France or recherche français ou étrangers, des laboratoires abroad, or from public or private research centers. publics ou privés. Published in Mon-Khmer Studies 39. 89–104 (2010). The origin of the peculiarities of the Vietnamese alphabet by André-Georges Haudricourt Translated by Alexis Michaud, LACITO-CNRS, France Originally published as: L’origine des particularités de l’alphabet vietnamien, Dân Việt Nam 3:61-68, 1949. Translator’s foreword André-Georges Haudricourt’s contribution to Southeast Asian studies is internationally acknowledged, witness the Haudricourt Festschrift (Suriya, Thomas and Suwilai 1985). However, many of Haudricourt’s works are not yet available to the English-reading public. A volume of the most important papers by André-Georges Haudricourt, translated by an international team of specialists, is currently in preparation. Its aim is to share with the English- speaking academic community Haudricourt’s seminal publications, many of which address issues in Southeast Asian languages, linguistics and social anthropology. -

Proposal for Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone

Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone Proposal for Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone Table of Contents 1. General Information 2 1.1 Use of Latin Script characters in domain names 3 1.2 Target Script for the Proposed Generation Panel 4 1.2.1 Diacritics 5 1.3 Countries with significant user communities using Latin script 6 2. Proposed Initial Composition of the Panel and Relationship with Past Work or Working Groups 7 3. Work Plan 13 3.1 Suggested Timeline with Significant Milestones 13 3.2 Sources for funding travel and logistics 16 3.3 Need for ICANN provided advisors 17 4. References 17 1 Generation Panel for Latin Script Label Generation Ruleset for the Root Zone 1. General Information The Latin script1 or Roman script is a major writing system of the world today, and the most widely used in terms of number of languages and number of speakers, with circa 70% of the world’s readers and writers making use of this script2 (Wikipedia). Historically, it is derived from the Greek alphabet, as is the Cyrillic script. The Greek alphabet is in turn derived from the Phoenician alphabet which dates to the mid-11th century BC and is itself based on older scripts. This explains why Latin, Cyrillic and Greek share some letters, which may become relevant to the ruleset in the form of cross-script variants. The Latin alphabet itself originated in Italy in the 7th Century BC. The original alphabet contained 21 upper case only letters: A, B, C, D, E, F, Z, H, I, K, L, M, N, O, P, Q, R, S, T, V and X. -

Proposal for Superscript Diacritics for Prenasalization, Preglottalization, and Preaspiration

1 Proposal for superscript diacritics for prenasalization, preglottalization, and preaspiration Patricia Keating Department of Linguistics, UCLA [email protected] Daniel Wymark Department of Linguistics, UCLA [email protected] Ryan Sharif Department of Linguistics, UCLA [email protected] ABSTRACT The IPA currently does not specify how to represent prenasalization, preglottalization, or preaspiration. We first review some current transcription practices, and phonetic and phonological literature bearing on the unitary status of prenasalized, preglottalized and preaspirated segments. We then propose that the IPA adopt superscript diacritics placed before a base symbol for these three phenomena. We also suggest how the current IPA Diacritics chart can be modified to allow these diacritics to be fit within the chart. 2 1 Introduction The IPA provides a variety of diacritics which can be added to base symbols in various positions: above ([a͂ ]), below ([n̥ ]), through ([ɫ]), superscript after ([tʰ]), or centered after ([a˞]). Currently, IPA diacritics which modify base symbols are never shown preceding them; the only diacritics which precede are the stress marks, i.e. primary ([ˈ]) and secondary ([ˌ]) stress. Yet, in practice, superscript diacritics are often used preceding base symbols; specifically, they are often used to notate prenasalization, preglottalization and preaspiration. These terms are very common in phonetics and phonology, each having thousands of Google hits. However, none of these phonetic phenomena is included on the IPA chart or mentioned in Part I of the Handbook of the International Phonetic Association (IPA 1999), and thus there is currently no guidance given to users about transcribing them. In this note we review these phenomena, and propose that the Association’s alphabet include superscript diacritics preceding the base symbol for prenasalization, preglottalization and preaspiration, in accord with one common way of transcribing them. -

Glottal and Epiglottal Stop in Wakashan, Salish, and Semitic

Glottal and Epiglottal Stop in Wakashan, Salish, and Semitic John H. Esling Department of Linguistics, University of Victoria, Canada E-mail: [email protected] ABSTRACT 2. RESEARCH APPROACH Direct laryngoscopic articulatory evidence from four We have examined the laryngeal physiology involved in languages in three unrelated families demonstrates the the production of glottal, glottalized, and pharyngeal existence of epiglottal stop in the pharyngeal series. In consonants in Nuuchahnulth (Wakashan), Nlaka’pamux each language, Nuuchahnulth (Wakashan), Nlaka’pamux (Salish), Arabic (Semitic), and Tigrinya (Semitic) to (Salish), Arabic (Semitic), and Tigrinya (Semitic), glottal identify the role of the aryepiglottic sphincter mechanism. stop also exists in the glottal series as a complement to In general, we wish to discover how sounds originating in epiglottal stop, and in three of the languages, a voiceless the lower pharynx are produced and how they are related glottal fricative and a voiceless pharyngeal fricative are to each other articulatorily. Specifically, we wish to also found. In Nlaka’pamux, a pair of voiced pharyngeal demonstrate how stop articulations in the laryngeal and approximants (sometimes realized as pharyngealized pharyngeal regions are produced and to document the uvulars) is found instead of the voiceless pharyngeal production of epiglottal stop. The key element in this fricative. As the most extreme stricture in either the glottal research is to document linguistic examples from native or the pharyngeal series, epiglottal stop is a product of full speakers of the cardinal consonantal categories predicted constriction of the aryepiglottic laryngeal sphincter and in prior studies of laryngeal and pharyngeal articulatory functions as the physiological mechanism for optimally possibilities [15,16]. -

78. 78. Nasal Harmony Nasal Harmony

Bibliographic Details The Blackwell Companion to Phonology Edited by: Marc van Oostendorp, Colin J. Ewen, Elizabeth Hume and Keren Rice eISBN: 9781405184236 Print publication date: 2011 78. Nasal Harmony RACHEL WWALKER Subject Theoretical Linguistics » Phonology DOI: 10.1111/b.9781405184236.2011.00080.x Sections 1 Nasal vowel–consonant harmony with opaque segments 2 Nasal vowel–consonant harmony with transparent segments 3 Nasal consonant harmony 4 Directionality 5 Conclusion ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Notes REFERENCES Nasal harmony refers to phonological patterns where nasalization is transmitted in long-distance fashion. The long-distance nature of nasal harmony can be met by the transmission of nasalization either to a series of segments or to a non-adjacent segment. Nasal harmony usually occurs within words or a smaller domain, either morphologically or prosodically defined. This chapter introduces the chief characteristics of nasal harmony patterns with exemplification, and highlights related theoretical themes. It focuses primarily on the different roles that segments can play in nasal harmony, and the typological properties to which they give rise. The following terminological conventions will be assumed. A trigger is a segment that initiates nasal harmony. A target is a segment that undergoes harmony. An opaque segment or blocker halts nasal harmony. A transparent segment is one that does not display nasalization within a span of nasal harmony, but does not halt harmony from transmitting beyond it. Three broad categories of nasal harmony are considered in this chapter. They are (i) nasal vowel–consonant harmony with opaque segments, (ii) nasal vowel– consonant harmony with transparent segments, and (iii) nasal consonant harmony. Each of these groups of systems show characteristic hallmarks. -

Title Glottal Stop in Cleft Palate Speech Author(S)

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Kyoto University Research Information Repository Title Glottal Stop in Cleft Palate Speech Kido, Naohiro; Kawano, Michio; Tanokuchi, Fumiko; Author(s) Fujiwara, Yuri; Honjo, Iwao; Kojima, Hisayoshi Citation 音声科学研究 = Studia phonologica (1992), 26: 34-41 Issue Date 1992 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2433/52465 Right Type Departmental Bulletin Paper Textversion publisher Kyoto University STUDIA PHONOLOGICA XXVI (1992) Glottal Stop in Cleft Palate Speech Naohiro Kmo, Michio KAWANO, Fumiko TANOKUCHI, Yuri FUJIWARA, Iwao HONJO AND Hisayoshi KOJIMA INTRODUCTION There is a great deal of literature that deals with the glottal stop, one of the abnormal articulations found in cleft palate speech. Except for some earlier research by Kawano,l) very few descriptions of the articulatory movements involved in these glottal stops is available in the literature. The present study expands upon that ear lier research and examines two cases in order to illustrate the process by which glot tal stop production is corrected. METHOD The subjects were 26 cleft palate patients who were seen at our clinic during the 5 years from 1984 to 1988. Their productions ofJapanese voiceless stops were auditorilly judged to be glottal stops which were confirmed by fiberscopic assessment of their laryngeal behavior. Age at the time of fiberscopic evaluation ranged from 5 to 53 years, with the mean age being 23.6. Eighteen of the subjects were judged to exhibit significant velopharyngeal insufficiency while 8 demonstrated slight velo pharyngeal insufficiency. Individuals with mental retardation or bilateral hearing loss were excluded from the study (see Table 1). -

Why Do Glottal Stops and Low Vowels Like Each Other?

ICPhS XVII Regular Session Hong Kong, 17-21 August 2011 WHY DO GLOTTAL STOPS AND LOW VOWELS LIKE EACH OTHER? Jana Brunner & Marzena Żygis Centre for General Linguistics, Berlin, Germany [email protected]; [email protected] ABSTRACT 1.1. Phonological processes The aim of the present study is two-fold. First, we In Klallam (a Salish language), the non-low will show that glottal stops/glottalization and low vowels /i u ə/ are lowered to /ε o a/, respectively, w vowels are likely to co-occur in typologically when followed by [ʔ]. For example, /pʔíх ŋ/ is w different languages. Second, we will investigate pronounced as [pʔεʔх ŋ] ‘overflow’/‘overflowing’ the question whether this widely attested co- and /šúpt/ as [šóʔpt] ‘whistle’/‘whistling’ [17]. occurrence of glottalization and low vowels could In the reduplication processes in Nisgha (a be due to a perceptual phenomenon; i.e. Tsimshianic language) the quality of the vowel in differences in the perception of vowel quality of the prefix depends on the surrounding segments. If glottalized as compared to non-glottalized vowels. the stem starts with a coronal stop, the vowel in the We hypothesized that vowels are perceived lower prefix is also coronal: /tamʔ/ is reduplicated to in their height if they are glottalized. In order to [tim-tamʔ] ‘to press’ but if the initial-stem test our hypothesis we conducted a perceptual consonant is a glottal stop the vowel in the prefix experiment with two German continua of b[i]ten- is the low vowel [a]: /ʔux/ is pronounced as [ʔax- b[e]ten (‘to offer’, ‘to pray’), a non-glottalized and ʔux] ‘to throw’ ([14], [15]). -

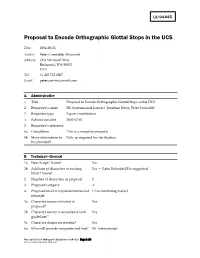

Proposal to Encode Orthographic Glottal Stops in the UCS

L2/04-065 Proposal to Encode Orthographic Glottal Stops in the UCS Date: 2004-02-01 Author: Peter Constable, Microsoft Address: One Microsoft Way Redmond, WA 98052 USA Tel: +1 425 722 1867 Email: [email protected] A. Administrative 1. Title Proposal to Encode Orthographic Glottal Stops in the UCS 2. Requester’s name SIL International (contact: Jonathan Kew), Peter Constable 3. Requester type Expert contribution 4. Submission date 2004-02-01 5. Requester’s reference 6a. Completion This is a complete proposal 6b. More information to Only as required for clarification. be provided? B. Technical—General 1a. New Script? Name? No 1b. Addition of characters to existing Yes — Latin Extended B is suggested block? Name? 2. Number of characters in proposal 2 3. Proposed category A 4. Proposed level of implementation and 1 (no combining marks) rationale 5a. Character names included in Yes proposal? 5b. Character names in accordance with Yes guidelines? 5c. Character shapes reviewable? Yes 6a. Who will provide computerized font? SIL International Proposal to Encode Orthographic Glottal Stops in the UCS Page 1 of 6 Peter G. Constable February 01, 2004 Rev: 7 6b. Font currently available? Yes 6c. Font format? TrueType 7a. Are references (to other character sets, Yes dictionaries, descriptive texts, etc.) provided? 7b. Are published examples (such as Yes samples from newspapers, magazines, or other sources) of use of proposed characters attached? 8. Does the proposal address other Yes, suggested character properties are included (see aspects of character data processing? section D). C. Technical—Justification 1. Has this proposal for addition of No character(s) been submitted before? 2a. -

The Damascus Psalm Fragment Oi.Uchicago.Edu

oi.uchicago.edu The Damascus Psalm Fragment oi.uchicago.edu ********** Late Antique and Medieval Islamic Near East (LAMINE) The new Oriental Institute series LAMINE aims to publish a variety of scholarly works, including monographs, edited volumes, critical text editions, translations, studies of corpora of documents—in short, any work that offers a significant contribution to understanding the Near East between roughly 200 and 1000 CE ********** oi.uchicago.edu The Damascus Psalm Fragment Middle Arabic and the Legacy of Old Ḥigāzī by Ahmad Al-Jallad with a contribution by Ronny Vollandt 2020 LAMINE 2 LATE ANTIQUE AND MEDIEVAL ISLAMIC NEAR EAST • NUMBER 2 THE ORIENTAL INSTITUTE OF THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO CHICAGO, ILLINOIS oi.uchicago.edu Library of Congress Control Number: 2020937108 ISBN: 978-1-61491-052-7 © 2020 by the University of Chicago. All rights reserved. Published 2020. Printed in the United States of America. The Oriental Institute, Chicago THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO LATE ANTIQUE AND MEDIEVAL ISLAMIC NEAR EAST • NUMBER 2 Series Editors Charissa Johnson and Steven Townshend with the assistance of Rebecca Cain Printed by M & G Graphics, Chicago, IL Cover design by Steven Townshend The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Services — Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1984. ∞ oi.uchicago.edu For Victor “Suggs” Jallad my happy thought oi.uchicago.edu oi.uchicago.edu Table of Contents Preface............................................................................... ix Abbreviations......................................................................... xi List of Tables and Figures ............................................................... xiii Bibliography.......................................................................... xv Contributions 1. The History of Arabic through Its Texts .......................................... 1 Ahmad Al-Jallad 2. -

Kelsea Hosoda

Kelsea Kanohokuahiwi Hosoda ICS 661 Spring 2017 Professor David Chin Identifying and Categorizing Word Ambiguities due to Diacritical Markers within a single Hawaiian Language Corpus Introduction Background The Hawaiian language has a rich history that includes a thriving language boasting the most literate nation in the late 1800s to less than one thousand Native speakers in the 1950s and is now a leading language in revitalization efforts (Warchauer, 1997). The Hawaiian language has an advantage in its revitalization because of the documentation, preservation, and digitization efforts starting from the 1840s including Hawaiian language newspapers, oral histories, and video recordings of elders (Berez, 2013; Nogelmeir, 2003; Papa Kilo, 2017). These documents are crucial to the revitalization efforts of researchers and students alike to developing the next generation of Hawaiian language speakers and understanding the Hawaiian culture (Grenoble, 2006). The Hawaiian people recognized the power of documenting the Hawaiian language in a printed form. For example, the very first Hawaiian newspaper article published in 1834 states the importance of documenting the language for future generations (Solomona, 1834). From the first Hawaiian newspaper, there were over 40 different Hawaiian language newspapers printed and dispersed between 1834 and the 1980s (Nogelmeir, 2003). The Hawaiian language newspapers have been archived and recently a large subset has been digitized via the ‘Ike Kūʻokoʻa project (ʻIke Kūʻokoʻa 2017). The content of the newspapers included Hawaiian stories as well as mainstream factual information. There is a robust amount of information and cultural knowledge within the printed Hawaiian language documents (Nogelmeir 2003). Hawaiian Orthography Hawaiian orthography was first developed by American protestant missionaries in the 1820s (Schultz, 1994). -

The Three American T Sounds T Pronunciation #1: True T Or

Free, printable resource from San Diego Voice and Accent [email protected] The Three American T Sounds The T sound has three pronunciation variations depending on the context. However, most IPA dictionaries don’t differentiate between the three T sounds! You will most likely always see the /t/ symbol used in the IPA transcription, but that’s not always correct. T Pronunciation #1: True T or Released T /t/ This T sound is probably the one that you learned to pronounce. It is made by touching the tongue tip to the roof of the mouth, just behind the front teeth (the bumpy ridge called the alveolar ridge). Air builds behind the tongue, and then a puff of air is released as the tongue comes down. You use this T sound at the beginning of a word or syllable or within a t-cluster (two or more consonants that are together), like in tie, atomic, and institution. T Pronunciation #2: Flap /ɾ/ The flap is one of the sounds that makes American English different from other versions of English, and Americans use the flap frequently. It will improve your American accent greatly to learn about the flap! The flap is similar to a light D sound. You make a flap by lightly “flapping” the tongue tip to the roof of the mouth, just behind the front teeth (the bumpy ridge called the alveolar ridge). The flap is very quick - if you put too much time into the flap, then you will make an actual D sound. One important note: The flap is the same as the R sound in other languages, like in Spanish, in which a speaker will use a flap in the word caro /kaɾo/ (meaning expensive). -

Two Chamorro Orthographies and Their Differences

Two Chamorro Orthographies and their differences Sandy Chung University of California, Santa Cruz [email protected] March 2019 1 An Ideal Orthography • Systematic • Accurate – true to the structure of the language • Easy to learn • Connected to earlier ways of spelling the language – some legacy features are preserved March 2019 2 What’s Special about Chamorro • Language loss – more recent in the CNMI than in Guam • Ethnically and linguistically diverse classrooms • The easier it is for children to learn Chamorro spelling, the better the chances that the language will survive March 2019 3 Two Principles of Orthography • Two principles involved in designing a good orthography – “One sound, one symbol” – “One word, one spelling” March 2019 4 “One sound, one symbol” • This principle means: spell a given sound the same way everywhere – The sound /k/ is spelled the same way wherever it occurs, not k sometimes and g other times kulu, dikiki’, måolik – Glottal stop is spelled the same way wherever it occurs li’i’, palåo’an, sa’ March 2019 5 Ex. of “One sound, one symbol” • Languages whose orthographies obey “one sound, one symbol” – Hawaiian – Spanish (mostly) – Turkish ... But not English March 2019 6 “One word, one spelling” • This principle means: spell a given word the same way in all its different forms – The word electric is spelled the same way in all of its forms and in all the words derived from it electric, electricity, electrician /k/ /s/ /š/ March 2019 7 Ex. of “One word, one spelling” • Languages whose orthographies obey “one word,