Constructing Dystopia: Language, Violence, and Narrative Form in the Handmaid's Tale and a Clockwork Orange

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

What Kubrick's Kelley O'brien University of South Florida, [email protected]

University of South Florida Scholar Commons Graduate Theses and Dissertations Graduate School March 2018 "He Didn't Mean It": What Kubrick's Kelley O'Brien University of South Florida, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Film and Media Studies Commons Scholar Commons Citation O'Brien, Kelley, ""He Didn't Mean It": What Kubrick's" (2018). Graduate Theses and Dissertations. http://scholarcommons.usf.edu/etd/7204 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Graduate School at Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “He Didn‟t Mean It”: What Kubrick‟s The Shining Can Teach Us About Domestic Violence by Kelley O‟Brien A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Liberal Arts With a concentration in Humanities Department of Humanities and Cultural Studies College Arts and Sciences University of South Florida Major Professor: Daniel Belgrad, Ph.D. Maria Cizmic, Ph.D. Amy Rust Ph.D. Date of Approval: March 8, 2018 Keywords: Patriarchy, Feminism, Gender Politics, Horror, American 1970s Copyright © 2018, Kelley O‟Brien Dedication I dedicate this thesis project to my mother, Terri O‟Brien. Thank you for always supporting my dreams and for your years of advocacy in the fight to end violence against women. I could not have done this without you. Acknowledgments First I‟d like to express my gratitude to my thesis advisor Dr. -

A Clockwork Orange and Stanley Kubrick’S Film Adaptations

2016-2017 A dissertation submitted to Ghent University in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts – Linguistics and Literature: English & Dutch THE TRUTH BETWEEN THE LINES A Comparative Analysis of Unreliable Narration in Vladimir Nabokov’s Lolita, Anthony Burgess’s A Clockwork Orange and Stanley Kubrick’s Film Adaptations Name: Isaura Vanden Berghe Student number: 01304811 Supervisor: Marco Caracciolo ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my master’s dissertation advisor Assistant Professor of English and Literary Theory, Marco Caracciolo of the Department of Literary Studies at the University of Ghent. Whenever I needed guidance or had a question about my research or writing, Prof. Caracciolo was always quick to respond, steering me in the right direction whenever he thought I needed it. Then, I must also express my very profound gratitude to my parents and to my brother for providing me with continuous encouragement and unfailing support throughout my years of study and through the process of writing and researching this dissertation. This accomplishment would not have been possible without them. Thank you. TABLE OF CONTENT INTRODUCTION 1 THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK 5 THEORY OF UNRELIABLE NARRATION 5 UNRELIABLE NARRATION IN FILM 9 LOLITA 12 LOLITA: THE NOVEL (1955) 12 IN HUMBERT HUMBERT’S DEFENSE: A SUMMARY 12 UNRELIABLE NARRATION IN THE NOVEL 15 LOLITA: THE FILM (1962) 35 STANLEY KUBRICK AND ‘CINEMIZING’ THE NOVEL 35 UNRELIABLE NARRATION IN THE FILM 36 A CLOCKWORK ORANGE 47 A CLOCKWORK ORANGE: THE NOVEL (1962) 47 ALEX’S ULTRA-VIOLENT RETELLING: A SUMMARY 47 UNRELIABLE NARRATION IN THE NOVEL 50 A CLOCKWORK ORANGE: THE FILM (1972) 63 STANLEY KUBRICK’S ADAPTATION 63 UNRELIABLE NARRATION IN THE FILM 64 CONCLUSION 75 REFERENCES APPENDIX A APPENDIX B APPENDIX C INTRODUCTION In 2011, Mark Jacobs launched a campaign ad for a new fragrance of his, called ‘Oh, Lola!’1. -

Tournament Results 50 Oceania Circuit Events 52 Oceania Circuit Winners 53 Financial Accounts 54

ANNUAL REPORT 2011 Report & Financial Statements For Year Ending 31 December 2011 Front Cover Photograph 2011 Pacific Games Men‟s Singles Medalists Gold Medal Marc-Antoine Desaymoz (New Cal) Silver Medal Arnaud Franzi (New Cal) Bronze Medal William Jannic (New Cal) 2011 Annual Report www.oceaniabadminton.org Page 2 Content Page Officer Bearers 5 Committees 6 Presidents Report 7 Chief Operating Officers Report 9 Regional Development Officers Report 15 Committee Reports Technical Officials Committee 22 Women in Badminton 25 Events Committee 27 Players Advisory Group 30 Member Country Reports Australia 31 Tonga 36 Tuvalu 39 Tahiti 40 New Zealand 42 Guam 45 New Caledonia 46 Northern Marianas 4848 Tournament Results 50 Oceania Circuit Events 52 Oceania Circuit Winners 53 Financial Accounts 54 2011 Annual Report www.oceaniabadminton.org Page 3 2011 Annual Report www.oceaniabadminton.org Page 4 Office Bearers Executive Board Nigel Skelt New Zealand (President) Geraldine Brown Australia (Deputy President) Warren Yee Fiji Murray Weatherston New Zealand Loke Poh Wong Australia Karawa Areieta Kiribati Mathieu Dufermon New Caledonia Office Staff Corinne Barnard Chief Operating Officer Nadia Bleaken Regional Development Manager Bob Lindberg Bookkeeper Delegates Nigel Skelt BWF Vice President Geraldine Brown BWF Women in Badminton Committee Peter Cocker BWF Technical Officials Commission Rob Denton BWF Umpire Assessor Life Members Heather Robson 2011 Annual Report www.oceaniabadminton.org Page 5 Committees Technical Officials Peter Cocker (Australia) -

Glossary of Literary Terms

Glossary of Critical Terms for Prose Adapted from “LitWeb,” The Norton Introduction to Literature Study Space http://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/litweb10/glossary/C.aspx Action Any event or series of events depicted in a literary work; an event may be verbal as well as physical, so that speaking or telling a story within the story may be an event. Allusion A brief, often implicit and indirect reference within a literary text to something outside the text, whether another text (e.g. the Bible, a myth, another literary work, a painting, or a piece of music) or any imaginary or historical person, place, or thing. Ambiguity When we are involved in interpretation—figuring out what different elements in a story “mean”—we are responding to a work’s ambiguity. This means that the work is open to several simultaneous interpretations. Language, especially when manipulated artistically, can communicate more than one meaning, encouraging our interpretations. Antagonist A character or a nonhuman force that opposes, or is in conflict with, the protagonist. Anticlimax An event or series of events usually at the end of a narrative that contrast with the tension building up before. Antihero A protagonist who is in one way or another the very opposite of a traditional hero. Instead of being courageous and determined, for instance, an antihero might be timid, hypersensitive, and indecisive to the point of paralysis. Antiheroes are especially common in modern literary works. Archetype A character, ritual, symbol, or plot pattern that recurs in the myth and literature of many cultures; examples include the scapegoat or trickster (character type), the rite of passage (ritual), and the quest or descent into the underworld (plot pattern). -

THE TRENDS of STREAM of CONSCIOUSNESS TECHNIQUE in WILLIAM FAULKNER S NOVEL the SOUND and the FURY'' Chitra Yashwant Ga

AMIERJ Volume–VII, Issues– VII ISSN–2278-5655 Oct - Nov 2018 THE TRENDS OF STREAM OF CONSCIOUSNESS TECHNIQUE IN WILLIAM FAULKNER S NOVEL THE SOUND AND THE FURY’’ Chitra Yashwant Gaidhani Assistant Professor in English, G. E. Society RNC Arts, JDB Commerce and NSC Science College, Nashik Road, Tal. & Dist. Nashik, Maharashtra, India. Abstract: The term "Stream-of-Consciousness" signifies to a technique of narration. Prior to the twentieth century. In this technique an author would simply tell the reader what one of the characters was thinking? Stream-of-consciousness is a technique whereby the author writes as though inside the minds of the characters. Since the ordinary person's mind jumps from one event to another, stream-of- consciousness tries to capture this phenomenon in William Faulkner’s novel The Sound and Fury. This style of narration is also associate with the Modern novelist and story writers of the 20th century. The Sound and the Fury is a broadly significant work of literature. William Faulkner use of this technique Sound and Fury is probably the most successful and outstanding use that we have had. Faulkner has been admired for his ability to recreate the thought process of the human mind. In addition, it is viewed as crucial development in the stream-of-consciousness literary technique. According encyclopedia, in 1998, the Modern Library ranked The Sound and the Fury sixth on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century. The present research focuses on stream of consciousness technique used by William Faulkner’s novel “The Sound and Fury”. -

ELEMENTS of FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms That Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction

Dr. Hallett ELEMENTS OF FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms that Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction” is defined as any imaginative re-creation of life in prose narrative form. All fiction is a falsehood of sorts because it relates events that never actually happened to people (characters) who never existed, at least not in the manner portrayed in the stories. However, fiction writers aim at creating “legitimate untruths,” since they seek to demonstrate meaningful insights into the human condition. Therefore, fiction is “untrue” in the absolute sense, but true in the universal sense. Critical Thinking – analysis of any work of literature – requires a thorough investigation of the “who, where, when, what, why, etc.” of the work. Narrator / Narrative Voice Guiding Question: Who is telling the story? …What is the … Narrative Point of View is the perspective from which the events in the story are observed and recounted. To determine the point of view, identify who is telling the story, that is, the viewer through whose eyes the readers see the action (the narrator). Consider these aspects: A. Pronoun p-o-v: First (I, We)/Second (You)/Third Person narrator (He, She, It, They] B. Narrator’s degree of Omniscience [Full, Limited, Partial, None]* C. Narrator’s degree of Objectivity [Complete, None, Some (Editorial?), Ironic]* D. Narrator’s “Un/Reliability” * The Third Person (therefore, apparently Objective) Totally Omniscient (fly-on-the-wall) Narrator is the classic narrative point of view through which a disembodied narrative voice (not that of a participant in the events) knows everything (omniscient) recounts the events, introduces the characters, reports dialogue and thoughts, and all details. -

MASARYK UNIVERSITY Aspects of Postmodernism in Anthony Burgess

MASARYK UNIVERSITY FACULTY OF EDUCATION Department of English Language and Literature Aspects of Postmodernism in Anthony Burgess’ Novels Diploma thesis Brno 2011 Supervisor: PhDr. Pavel Doležel, Csc. Author: Bc. Radka Mikulaková Bibliographic note Mikulaková, Radka. Aspects of Postmodernism in Anthony Burgess’ novels. Brno: Masaryk University, Faculty of Education, Department of English Language and Literature, 2011. Supervisor Pavel Doležel. Anotace Diplomová práce Aspekty postmodernismu v románech Anthony Burgesse pojednává o literárním postmodernismu v románech Anthony Burgesse. Jmenovitě v románech A Clockwork Orange, The Wanting Seed a 1985, které jsou tematicky propojeny autorovou teorií vývoje moderní společnosti. Práce je rozdělena do tří základních oddílů. První část shrnuje základní literárněvědné přístupy k samotnému pojmu postmodernismus a stanovuje tak teoretická východiska k dalším oddílům práce. V následující části jsou výše uvedené romány podrobeny literární analýze z hlediska teorie fikčních světů a závěrem je stěžejní téma románů, Burgessova teorie cyklického vývoje společnosti, porovnáno a zkoumáno z hlediska dobových filozoficko-sociologických tendencí. Annotation Diploma thesis Aspects of Postmodernism in Anthony Burgess’ Novels deals with literary postmodernism in Anthony Burgess‟ novels, i.e. in A Clockwork Orange, The Wanting Seed and 1985, which are thematically connected by author‟s theory of the development of contemporary society. Thesis is divided into three chapters. The first chapter deals with basic scientific approaches to the term postmodernism and thus defines a theoretical basis for other chapters. In the following part the three of Burgess‟ novels are analyzed from the perspective of fictional semantics and, finally, the main theme of these Burgess‟ novels, a cyclic theory of human development, is compared and contrasted with the then socio-philosophical tendencies. -

Stream of Consciousness Technique: Psychological Perspectives and Use in Modern Novel المنظور النفسي واستخدا

Stream of Consciousness Technique: Psychological Perspectives and Use in Modern Novel Weam Majeed Alkhafaji Sajedeh Asna'ashari University of Kufa, College of Education Candle & Fog Publishing Company Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Abstract Stream of Consciousness technique has a great impact on writing literary texts in the modern age. This technique was broadly used in the late of nineteen century as a result of thedecay of plot, especially in novel writing. Novelists began to use stream of consciousness technique as a new phenomenon, because it goes deeper into the human mind and soul through involving it in writing. Modern novel has changed after Victorian age from the traditional novel that considers themes of religion, culture, social matters, etc. to be a group of irregular events and thoughts interrogate or reveal the inner feeling of readers. This study simplifies stream of consciousness technique through clarifying the three levels of conscious (Consciousness, Precociousness and Unconsciousness)as well as the subconsciousness, based on Sigmund Freud theory. It also sheds a light on the relationship between stream of consciousness, interior monologue, soliloquy and collective unconscious. Finally, This paper explains the beneficial aspects of the stream of consciousness technique in our daily life. It shows how this technique can releaseour feelings and emotions, as well as free our mind from the pressure of thoughts that are upsetting our mind . Key words: Stream of Consciousness, Modern novel, Consciousness, Precociousness and Unconsciousness and subconsciousness. تقنية انسياب اﻻفكار : المنظور النفسي واستخدامه في الرواية الحديثة وئام مجيد الخفاجي ساجدة اثنى عشري جامعة الكوفة – كلية التربية – قسم اللغة اﻻنكليزية دار نشر كاندل وفوك الخﻻصة ان لتقنية انسياب اﻻفكار تأثير كبير على كتابة النصوص اﻻدبية في العصر الحديث. -

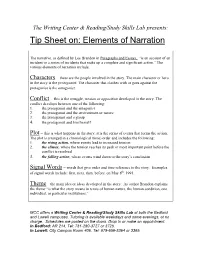

Elements of Narration

The Writing Center & Reading/Study Skills Lab presents: Tip Sheet on: Elements of Narration The narrative, as defined by Lee Brandon in Paragraphs and Essays, “is an account of an incident or a series of incidents that make up a complete and significant action.” The various elements of narration include: Characters – these are the people involved in the story. The main character or hero in the story is the protagonist. The character that clashes with or goes against the protagonist is the antagonist. Conflict – this is the struggle, tension or opposition developed in the story. The conflict develops between one of the following: 1. the protagonist and the antagonist 2. the protagonist and the environment or nature 3. the protagonist and a group 4. the protagonist and him/herself Plot – this is what happens in the story; it is the series of events that forms the action. The plot is arranged in a chronological (time) order and includes the following: 1. the rising action, where events lead to increased tension 2. the climax, where the tension reaches its peak or most important point before the conflict is resolved 3. the falling action, where events wind down to the story’s conclusion Signal Words – words that give order and time reference to the story. Examples of signal words include: first, next, then, before, on May 8th, 1991. Theme – the main idea or ideas developed in the story. As author Brandon explains, the theme “is what the story means in terms of human nature, the human condition, one individual, or particular institutions.” MCC offers a Writing Center & Reading/Study Skills Lab at both the Bedford and Lowell campuses. -

Philosophy of Action and Theory of Narrative1

PHILOSOPHY OF ACTION AND THEORY OF NARRATIVE1 TEUN A. VAN DIJK 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. The aim of this paper is to apply some recent results from the philosophy of action in the theory of narrative. The intuitive idea is that narrative discourse may be conceived of as a form of natural action description, whereas a philosophy or, more specifically, a logic of action attempts to provide formal action descriptions. It is expected that, on the one hand, narrative discourse is an interesting empirical testing ground for the theory of action, and that, on the other hand, formal action description may yield insight into the abstract structures of narratives in natural language. It is the latter aspect of this interdisciplinary inquiry which will be em- phasized in this paper. 1.2. If there is one branch of analytical philosophy which has received particular at- tention in the last ten years it certainly is the philosophy of action. Issued from classical discussions in philosophical psychology (Hobbes, Hume) the present analy- sis of action finds applications in the foundations of the social sciences, 2 in ethics 3 1This paper has issued from a seminar held at the University of Amsterdam in early 1974. Some of the ideas developed in it have been discussed in lectures given at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes (Paris), Louvain, Bielefeld, Münster, Ann Arbor, CUNY (New York) and Ant- werp, in 1973 and 1974. A shorter version of this paper has been published as Action, Action Description and Narrative in New literary history 6 (1975): 273-294. -

Distinguishing Narration and Speech in Prose Fiction Dialogues

Distinguishing Narration and Speech in Prose Fiction Dialogues Adam Eky and Mats Wirén Stockholm University, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden {adam.ek, mats.wiren}@ling.su.se Abstract. This paper presents a supervised method for a novel task, namely, detecting elements of narration in passages of dialogue in prose fiction. The method achieves an F1-score of 80.8%, exceeding the best baseline by almost 33 percentage points. The purpose of the method is to enable a more fine-grained analysis of fictional dialogue than has previously been possible, and to provide a component for the further analysis of narrative structure in general. Keywords: Prose fiction · Literary dialogue · Characters’ discourse · Narrative structure 1 Introduction Prose fiction typically consists of passages alternating between two levels of narrative transmission: the narrator’s telling of the story to a narratee, and the characters’ speaking to each other in that story (mediated by the narrator). As stated in [Dolezel, 1973], quoted in [Jahn, 2017, Section N8.1]: "Every narrative text T is a concatenation and alternation of ND [narrator’s discourse] and CD [characters’ discourse]". An example of this alternation can be found in August Strindberg’s The Red Room (1879), with our annotation added to it: (1) <NARRATOR> Olle very skilfully made a bag of one of the sheets and stuffed everything into it, while Lundell went on eagerly protesting. When the parcel was made, Olle took it under his arm, buttoned his ragged coat so as to hide the absence of a waistcoat, and set out on his way to the town. -

Gender and the Person in Oceania

Gender and Person in Oceania October 1-2, 2011 Hedley Bull Lecture Theatre 2 Hedley Bull Building The Australian National University This workshop is a collaboration between the ARC Laureate project Engendering Persons, Transforming Things led by Professor Margaret Jolly and the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales-ANU Pacific Dialogues project led by Professor Serge Tcherkézoff. It brings together a range of early and mid-career researchers from across Australia working in Oceania with Professor Irène Théry from EHESS in France and researchers from New Caledonia. Presentations will address the following themes Contending notions of gender as an attribute of the person or a mode of sociality The co-presence and dialectical tensions between models of the person as ‗dividuals‘/relational persons versus individuals How best to understand the situation of transgendered persons in Oceania The influence of Christianities and commodity economics on gender and personhood Changing patterns of intimacy, domesticity and marriage Women‘s role in conflicts, peace and Christianities in the region The significance of mobility and new technologies of modernity Papers presented will traverse many countries: the Cook Islands, Fiji, French Polynesia, New Caledonia, Papua New Guinea, Samoa, Solomon Islands, and Vanuatu. The program is listed over. The emphasis will be on dialogue and debate: short papers of c. 15 minutes are paired in panels and discussion time will be long. This workshop is free and open to all but registration is required for catering purposes, by Friday September 23, by email to [email protected] Gender and Person in Oceania October 1-2, 2011 Hedley Bull Theatre 2, Hedley Bull Building ANU Campus Saturday October 1 10.00 – 10.30 Morning Tea 10.30 – 10.45 Welcome and Introduction Margaret Jolly 10.45 – 11.30 Opening Address Chaired by Serge Tcherkézoff „From the sociology of gender in Western countries towards an anthropology of gender in the Pacific ..