Distinguishing Narration and Speech in Prose Fiction Dialogues

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Glossary of Literary Terms

Glossary of Critical Terms for Prose Adapted from “LitWeb,” The Norton Introduction to Literature Study Space http://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/litweb10/glossary/C.aspx Action Any event or series of events depicted in a literary work; an event may be verbal as well as physical, so that speaking or telling a story within the story may be an event. Allusion A brief, often implicit and indirect reference within a literary text to something outside the text, whether another text (e.g. the Bible, a myth, another literary work, a painting, or a piece of music) or any imaginary or historical person, place, or thing. Ambiguity When we are involved in interpretation—figuring out what different elements in a story “mean”—we are responding to a work’s ambiguity. This means that the work is open to several simultaneous interpretations. Language, especially when manipulated artistically, can communicate more than one meaning, encouraging our interpretations. Antagonist A character or a nonhuman force that opposes, or is in conflict with, the protagonist. Anticlimax An event or series of events usually at the end of a narrative that contrast with the tension building up before. Antihero A protagonist who is in one way or another the very opposite of a traditional hero. Instead of being courageous and determined, for instance, an antihero might be timid, hypersensitive, and indecisive to the point of paralysis. Antiheroes are especially common in modern literary works. Archetype A character, ritual, symbol, or plot pattern that recurs in the myth and literature of many cultures; examples include the scapegoat or trickster (character type), the rite of passage (ritual), and the quest or descent into the underworld (plot pattern). -

THE TRENDS of STREAM of CONSCIOUSNESS TECHNIQUE in WILLIAM FAULKNER S NOVEL the SOUND and the FURY'' Chitra Yashwant Ga

AMIERJ Volume–VII, Issues– VII ISSN–2278-5655 Oct - Nov 2018 THE TRENDS OF STREAM OF CONSCIOUSNESS TECHNIQUE IN WILLIAM FAULKNER S NOVEL THE SOUND AND THE FURY’’ Chitra Yashwant Gaidhani Assistant Professor in English, G. E. Society RNC Arts, JDB Commerce and NSC Science College, Nashik Road, Tal. & Dist. Nashik, Maharashtra, India. Abstract: The term "Stream-of-Consciousness" signifies to a technique of narration. Prior to the twentieth century. In this technique an author would simply tell the reader what one of the characters was thinking? Stream-of-consciousness is a technique whereby the author writes as though inside the minds of the characters. Since the ordinary person's mind jumps from one event to another, stream-of- consciousness tries to capture this phenomenon in William Faulkner’s novel The Sound and Fury. This style of narration is also associate with the Modern novelist and story writers of the 20th century. The Sound and the Fury is a broadly significant work of literature. William Faulkner use of this technique Sound and Fury is probably the most successful and outstanding use that we have had. Faulkner has been admired for his ability to recreate the thought process of the human mind. In addition, it is viewed as crucial development in the stream-of-consciousness literary technique. According encyclopedia, in 1998, the Modern Library ranked The Sound and the Fury sixth on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century. The present research focuses on stream of consciousness technique used by William Faulkner’s novel “The Sound and Fury”. -

ELEMENTS of FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms That Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction

Dr. Hallett ELEMENTS OF FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms that Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction” is defined as any imaginative re-creation of life in prose narrative form. All fiction is a falsehood of sorts because it relates events that never actually happened to people (characters) who never existed, at least not in the manner portrayed in the stories. However, fiction writers aim at creating “legitimate untruths,” since they seek to demonstrate meaningful insights into the human condition. Therefore, fiction is “untrue” in the absolute sense, but true in the universal sense. Critical Thinking – analysis of any work of literature – requires a thorough investigation of the “who, where, when, what, why, etc.” of the work. Narrator / Narrative Voice Guiding Question: Who is telling the story? …What is the … Narrative Point of View is the perspective from which the events in the story are observed and recounted. To determine the point of view, identify who is telling the story, that is, the viewer through whose eyes the readers see the action (the narrator). Consider these aspects: A. Pronoun p-o-v: First (I, We)/Second (You)/Third Person narrator (He, She, It, They] B. Narrator’s degree of Omniscience [Full, Limited, Partial, None]* C. Narrator’s degree of Objectivity [Complete, None, Some (Editorial?), Ironic]* D. Narrator’s “Un/Reliability” * The Third Person (therefore, apparently Objective) Totally Omniscient (fly-on-the-wall) Narrator is the classic narrative point of view through which a disembodied narrative voice (not that of a participant in the events) knows everything (omniscient) recounts the events, introduces the characters, reports dialogue and thoughts, and all details. -

Stream of Consciousness Technique: Psychological Perspectives and Use in Modern Novel المنظور النفسي واستخدا

Stream of Consciousness Technique: Psychological Perspectives and Use in Modern Novel Weam Majeed Alkhafaji Sajedeh Asna'ashari University of Kufa, College of Education Candle & Fog Publishing Company Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Abstract Stream of Consciousness technique has a great impact on writing literary texts in the modern age. This technique was broadly used in the late of nineteen century as a result of thedecay of plot, especially in novel writing. Novelists began to use stream of consciousness technique as a new phenomenon, because it goes deeper into the human mind and soul through involving it in writing. Modern novel has changed after Victorian age from the traditional novel that considers themes of religion, culture, social matters, etc. to be a group of irregular events and thoughts interrogate or reveal the inner feeling of readers. This study simplifies stream of consciousness technique through clarifying the three levels of conscious (Consciousness, Precociousness and Unconsciousness)as well as the subconsciousness, based on Sigmund Freud theory. It also sheds a light on the relationship between stream of consciousness, interior monologue, soliloquy and collective unconscious. Finally, This paper explains the beneficial aspects of the stream of consciousness technique in our daily life. It shows how this technique can releaseour feelings and emotions, as well as free our mind from the pressure of thoughts that are upsetting our mind . Key words: Stream of Consciousness, Modern novel, Consciousness, Precociousness and Unconsciousness and subconsciousness. تقنية انسياب اﻻفكار : المنظور النفسي واستخدامه في الرواية الحديثة وئام مجيد الخفاجي ساجدة اثنى عشري جامعة الكوفة – كلية التربية – قسم اللغة اﻻنكليزية دار نشر كاندل وفوك الخﻻصة ان لتقنية انسياب اﻻفكار تأثير كبير على كتابة النصوص اﻻدبية في العصر الحديث. -

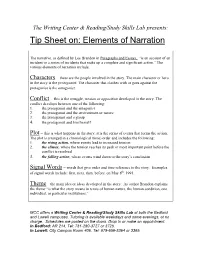

Elements of Narration

The Writing Center & Reading/Study Skills Lab presents: Tip Sheet on: Elements of Narration The narrative, as defined by Lee Brandon in Paragraphs and Essays, “is an account of an incident or a series of incidents that make up a complete and significant action.” The various elements of narration include: Characters – these are the people involved in the story. The main character or hero in the story is the protagonist. The character that clashes with or goes against the protagonist is the antagonist. Conflict – this is the struggle, tension or opposition developed in the story. The conflict develops between one of the following: 1. the protagonist and the antagonist 2. the protagonist and the environment or nature 3. the protagonist and a group 4. the protagonist and him/herself Plot – this is what happens in the story; it is the series of events that forms the action. The plot is arranged in a chronological (time) order and includes the following: 1. the rising action, where events lead to increased tension 2. the climax, where the tension reaches its peak or most important point before the conflict is resolved 3. the falling action, where events wind down to the story’s conclusion Signal Words – words that give order and time reference to the story. Examples of signal words include: first, next, then, before, on May 8th, 1991. Theme – the main idea or ideas developed in the story. As author Brandon explains, the theme “is what the story means in terms of human nature, the human condition, one individual, or particular institutions.” MCC offers a Writing Center & Reading/Study Skills Lab at both the Bedford and Lowell campuses. -

Philosophy of Action and Theory of Narrative1

PHILOSOPHY OF ACTION AND THEORY OF NARRATIVE1 TEUN A. VAN DIJK 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. The aim of this paper is to apply some recent results from the philosophy of action in the theory of narrative. The intuitive idea is that narrative discourse may be conceived of as a form of natural action description, whereas a philosophy or, more specifically, a logic of action attempts to provide formal action descriptions. It is expected that, on the one hand, narrative discourse is an interesting empirical testing ground for the theory of action, and that, on the other hand, formal action description may yield insight into the abstract structures of narratives in natural language. It is the latter aspect of this interdisciplinary inquiry which will be em- phasized in this paper. 1.2. If there is one branch of analytical philosophy which has received particular at- tention in the last ten years it certainly is the philosophy of action. Issued from classical discussions in philosophical psychology (Hobbes, Hume) the present analy- sis of action finds applications in the foundations of the social sciences, 2 in ethics 3 1This paper has issued from a seminar held at the University of Amsterdam in early 1974. Some of the ideas developed in it have been discussed in lectures given at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes (Paris), Louvain, Bielefeld, Münster, Ann Arbor, CUNY (New York) and Ant- werp, in 1973 and 1974. A shorter version of this paper has been published as Action, Action Description and Narrative in New literary history 6 (1975): 273-294. -

Narrative in Culture: the Uses of Storytelling in the Sciences

WARWICK STUDIES IN PHILOSOPHY AND LITERATURE General editor: David Wood In both philosophical and literary studies much of the best original work today explores both the tensions and the intricate connections between what have often been treated as separate fields. In philosophy there is a widespread conviction that the notion of an unmediated search for truth represents an over- simplification of the philosopher’s task, and that the language of philosophical argument requires its own interpretation. Even in the most rigorous instances of the analytic tradition, a tradition inspired by the possibilities of formalization and by the success of the natural sciences, we find demands for ‘clarity’, for ‘tight’ argument, and distinctions between ‘strong’ and ‘weak’ proofs which call out for a rhetorical reading—even for an aesthetic of argument. In literature many of the categories presupposed by traditions which give priority to ‘enactment’ over ‘description’ and oppose ‘theory’ in the name of ‘lived experience’ are themselves under challenge as requiring theoretical analysis, while it is becoming increasingly clear that to exclude literary works from philosophical probing is to trivialize many of them. Further, modern literary theory necessarily looks to philosophy to articulate its deepest problems and the effects of this are transmitted in turn to critical reading, as the widespread influence of deconstruction and of a more reflective hermeneutics has begun to show. When one recalls that Plato, who wished to keep philosophy and poetry apart, actually unified the two in his own writing, it is clear that the current upsurge of interest in this field is only re-engaging with the questions alive in the broader tradition. -

Stream-Of-Consciousness Techniques

Stream-of-consciousness techniques • Representation of Consciousness • Rather more intricate than representations of speech in direct or indirect mode are representations of thought, which can be conceptualised as a kind of silent speech or inner speech. Obviously, it is possible simply to represent thought, just like speech, using direct or indirect discourse: • "What horrible weather they have here," he thought. (direct discourse ) • He thought that the weather in these parts was really horrible. ( indirect discourse ) Stream-of-consciousness techniques • Free indirect speech is a style of third- person narration which combines some of the characteristics of third-person report with first-person direct speech. (It is also referred to as free indirect discourse , free indirect style Stream-of-consciousness techniques • Comparison of styles • What distinguishes free indirect speech from normal indirect speech, is the lack of an introductory expression such as "He said" or "he thought". It is as if the subordinate clause carrying the content of the indirect speech is taken out of the main clause which contains it, becoming the main clause itself. Using free indirect speech may convey the character's words more directly than in normal indirect, as he can use devices such as interjections and exclamation marks, that cannot be normally used within a subordinate clause. Stream-of-consciousness techniques • Examples – Direct speech : • He laid down his bundle and thought of his misfortune. "And just what pleasure have I found, since I came into this world?" he asked. – Indirect speech : • He laid down his bundle and thought of his misfortune. He asked himself what pleasure he had found since he came into the world. -

Transmedial Narration Narratives and Stories in Different Media

Transmedial Narration Narratives and Stories in Different Media Lars Elleström Transmedial Narration Lars Elleström Transmedial Narration Narratives and Stories in Different Media Lars Elleström Department of Film and Literature Linnaeus University Växjö, Sweden ISBN 978-3-030-01293-9 ISBN 978-3-030-01294-6 (eBook) https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-01294-6 Library of Congress Control Number: 2018960865 © The Editor(s) (if applicable) and The Author(s) 2019 This book is an open access publication Open Access This book is licensed under the terms of the Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/), which permits use, sharing, adaptation, distribution and reproduction in any medium or format, as long as you give appropriate credit to the original author(s) and the source, provide a link to the Creative Commons licence and indicate if changes were made. The images or other third party material in this book are included in the book’s Creative Commons licence, unless indicated otherwise in a credit line to the material. If material is not included in the book’s Creative Commons licence and your intended use is not permitted by statutory regulation or exceeds the permitted use, you will need to obtain permission directly from the copyright holder. The use of general descriptive names, registered names, trademarks, service marks, etc. in this publication does not imply, even in the absence of a specific statement, that such names are exempt from the relevant protective laws and regulations and therefore free for general use. The publisher, the authors and the editors are safe to assume that the advice and information in this book are believed to be true and accurate at the date of publication. -

Pia in Keith Roberts' Molly Zero

Iina-Maria Talvinen SECOND-PERSON NARRATION AND DYSTO- PIA IN KEITH ROBERTS’ MOLLY ZERO Faculty of Information Technology and Communication Sciences Bachelor’s Thesis May 2021 ABSTRACT Iina-Maria Talvinen: Second-Person Narration and Dystopia in Keith Roberts’ Molly Zero Bachelor’s Thesis Tampere University Degree Programme in English Language, Literature and Translation May 2021 This thesis examines second-person narration and dystopia in Keith Roberts’ young adult science fiction novel Molly Zero (1980). The story takes place in a speculative yet believa- ble future of post-nuclear England. The novel’s protagonist is approximately 15-year-old Molly, who is struggling to navigate this world of mass surveillance and government prop- aganda. Molly’s story is closely bound in the central themes of the novel, the loss of indi- vidualism and identity. The purpose of this thesis is to study second-person narration’s abilities to produce dystopia and the loss of identity in Molly Zero’s inner world. The theory section of this thesis concentrates on the problematic nature of the second- person narrative and while acknowledging the achievements of earlier narratologists, it strives to examine second-person storytelling through new perspectives. In addition, a brief introduction of the protagonists of dystopian fiction in different eras is presented in order to position Molly Zero in its contextual time frame. The analysis section is divided in two parts, and the first section concentrates on second-person narration’s usefulness in producing dystopia through its immediateness and limited perspective. The second section investigates Molly’s character’s indefiniteness, passiveness and need for attention. -

William Faulkner's Narrative Mode In

Humanities and Social Sciences Review, CD-ROM. ISSN: 2165-6258 :: 2(2):193–202 (2013) WILLIAM FAULKNER’S NARRATIVE MODE IN “THE SOUND AND THE FURY’’A STREAM OF CONSCIOUSNESS TECHNIQUE OR INTERIOR MONOLOGUE USED IN BENJY’S SECTION Tatiana Vepkhvadze International Black Sea University, Georgia The present research analyzes William Faulkner’s writing style in “The Sound and Fury”, it refers to the stream of consciousness technique called interior monologue. The term is borrowed from drama, where ‘monologue’ refers to the part in a play where an actor expresses his inner thoughts aloud to the audience. The interior monologue represents an attempt to transcribe a character’s thoughts, sensations and emotions. In order to faithfully represent the rhythm and flow of consciousness, the writer often disregards traditional syntax, punctuation and logical connections. He does not intervene to guide the reader or to impose narrative order on the often confused, and confusing, mental processes. Stream of consciousness is now widely used in modern fiction as a narrative method to reveal the character’s unspoken thoughts and feelings without having recourse to dialogue or description. Faulkner’s handling of stream of consciousness technique allows the FID narrator to shape a particular version of the character’s consciousness in terms of images, which need not be actual words or thoughts as the character expressed them. The use of interior monologue is common narrative mode of Benjy’s section that makes the text absolutely ambiguous for the reader. Benjy can’t speak and being a narrator of the first section ,we have an access to the plot of the story through his perceptions and feelings. -

Contemporary Historical Fiction and Historiographical Theory

Based on a True Story: Contemporary Historical Fiction and Historiographical Theory Samantha Young This article considers the history of the historical novel, alongside the development of contemporary historiographic theory. It maps the development of the historical novel from its popular form in the nineteenth-century Romantic period, a time when the novels of Charles Dickens or Victor Hugo were rarely subject to critical appraisal, through to the contemporary, postmodern mode where historical narrative is often scrutinised for its (re)presentation of historical „truth‟. I analyse the works of writers such as Julian Barnes and Jonathan Safran Foer to reflect the blurred lines between narrative histories and stories told in the traditional mode. I ask scholars and readers of the past to overcome their demand that historical works must always present clear, documented evidence to be taken as true, and challenge the assumption that all fictions are merely stories conjured in a writer‟s mind. This article examines how much „truth‟ a fictive text may command, and asks that narrative is not seen to be compromising „truth‟ but instead in terms of its ability to offer readers access to a past unavailable to traditional or „proper‟ modes of historical research. I argue that narrative history allows experience an opportunity, and that it is often the encounters we have and the stories we tell that make history accessible, memorable and applicable to our present. Ways and Means: To Blur, but not Sacrifice, the Laws of Fact and Fiction Narrative histories, or historical fictions, have not been readily accepted in the academy as a legitimate form of history.