Toward Figural Fantasy

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia

10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia Hugo Award Hugo Award, any of several annual awards presented by the World Science Fiction Society (WSFS). The awards are granted for notable achievement in science �ction or science fantasy. Established in 1953, the Hugo Awards were named in honour of Hugo Gernsback, founder of Amazing Stories, the �rst magazine exclusively for science �ction. Hugo Award. This particular award was given at MidAmeriCon II, in Kansas City, Missouri, on August … Michi Trota Pin, in the form of the rocket on the Hugo Award, that is given to the finalists. Michi Trota Hugo Awards https://www.britannica.com/print/article/1055018 1/10 10/10/2017 Hugo Award -- Britannica Online Encyclopedia year category* title author 1946 novel The Mule Isaac Asimov (awarded in 1996) novella "Animal Farm" George Orwell novelette "First Contact" Murray Leinster short story "Uncommon Sense" Hal Clement 1951 novel Farmer in the Sky Robert A. Heinlein (awarded in 2001) novella "The Man Who Sold the Moon" Robert A. Heinlein novelette "The Little Black Bag" C.M. Kornbluth short story "To Serve Man" Damon Knight 1953 novel The Demolished Man Alfred Bester 1954 novel Fahrenheit 451 Ray Bradbury (awarded in 2004) novella "A Case of Conscience" James Blish novelette "Earthman, Come Home" James Blish short story "The Nine Billion Names of God" Arthur C. Clarke 1955 novel They’d Rather Be Right Mark Clifton and Frank Riley novelette "The Darfsteller" Walter M. Miller, Jr. short story "Allamagoosa" Eric Frank Russell 1956 novel Double Star Robert A. Heinlein novelette "Exploration Team" Murray Leinster short story "The Star" Arthur C. -

Glossary of Literary Terms

Glossary of Critical Terms for Prose Adapted from “LitWeb,” The Norton Introduction to Literature Study Space http://www.wwnorton.com/college/english/litweb10/glossary/C.aspx Action Any event or series of events depicted in a literary work; an event may be verbal as well as physical, so that speaking or telling a story within the story may be an event. Allusion A brief, often implicit and indirect reference within a literary text to something outside the text, whether another text (e.g. the Bible, a myth, another literary work, a painting, or a piece of music) or any imaginary or historical person, place, or thing. Ambiguity When we are involved in interpretation—figuring out what different elements in a story “mean”—we are responding to a work’s ambiguity. This means that the work is open to several simultaneous interpretations. Language, especially when manipulated artistically, can communicate more than one meaning, encouraging our interpretations. Antagonist A character or a nonhuman force that opposes, or is in conflict with, the protagonist. Anticlimax An event or series of events usually at the end of a narrative that contrast with the tension building up before. Antihero A protagonist who is in one way or another the very opposite of a traditional hero. Instead of being courageous and determined, for instance, an antihero might be timid, hypersensitive, and indecisive to the point of paralysis. Antiheroes are especially common in modern literary works. Archetype A character, ritual, symbol, or plot pattern that recurs in the myth and literature of many cultures; examples include the scapegoat or trickster (character type), the rite of passage (ritual), and the quest or descent into the underworld (plot pattern). -

JUDITH MERRIL-PDF-Sep23-07.Pdf (368.7Kb)

JUDITH MERRIL: AN ANNOTATED BIBLIOGRAPHY AND GUIDE Compiled by Elizabeth Cummins Department of English and Technical Communication University of Missouri-Rolla Rolla, MO 65409-0560 College Station, TX The Center for the Bibliography of Science Fiction and Fantasy December 2006 Table of Contents Preface Judith Merril Chronology A. Books B. Short Fiction C. Nonfiction D. Poetry E. Other Media F. Editorial Credits G. Secondary Sources About Elizabeth Cummins PREFACE Scope and Purpose This Judith Merril bibliography includes both primary and secondary works, arranged in categories that are suitable for her career and that are, generally, common to the other bibliographies in the Center for Bibliographic Studies in Science Fiction. Works by Merril include a variety of types and modes—pieces she wrote at Morris High School in the Bronx, newsletters and fanzines she edited; sports, westerns, and detective fiction and non-fiction published in pulp magazines up to 1950; science fiction stories, novellas, and novels; book reviews; critical essays; edited anthologies; and both audio and video recordings of her fiction and non-fiction. Works about Merill cover over six decades, beginning shortly after her first science fiction story appeared (1948) and continuing after her death (1997), and in several modes— biography, news, critical commentary, tribute, visual and audio records. This new online bibliography updates and expands the primary bibliography I published in 2001 (Elizabeth Cummins, “Bibliography of Works by Judith Merril,” Extrapolation, vol. 42, 2001). It also adds a secondary bibliography. However, the reasons for producing a research- based Merril bibliography have been the same for both publications. Published bibliographies of Merril’s work have been incomplete and often inaccurate. -

THE TRENDS of STREAM of CONSCIOUSNESS TECHNIQUE in WILLIAM FAULKNER S NOVEL the SOUND and the FURY'' Chitra Yashwant Ga

AMIERJ Volume–VII, Issues– VII ISSN–2278-5655 Oct - Nov 2018 THE TRENDS OF STREAM OF CONSCIOUSNESS TECHNIQUE IN WILLIAM FAULKNER S NOVEL THE SOUND AND THE FURY’’ Chitra Yashwant Gaidhani Assistant Professor in English, G. E. Society RNC Arts, JDB Commerce and NSC Science College, Nashik Road, Tal. & Dist. Nashik, Maharashtra, India. Abstract: The term "Stream-of-Consciousness" signifies to a technique of narration. Prior to the twentieth century. In this technique an author would simply tell the reader what one of the characters was thinking? Stream-of-consciousness is a technique whereby the author writes as though inside the minds of the characters. Since the ordinary person's mind jumps from one event to another, stream-of- consciousness tries to capture this phenomenon in William Faulkner’s novel The Sound and Fury. This style of narration is also associate with the Modern novelist and story writers of the 20th century. The Sound and the Fury is a broadly significant work of literature. William Faulkner use of this technique Sound and Fury is probably the most successful and outstanding use that we have had. Faulkner has been admired for his ability to recreate the thought process of the human mind. In addition, it is viewed as crucial development in the stream-of-consciousness literary technique. According encyclopedia, in 1998, the Modern Library ranked The Sound and the Fury sixth on its list of the 100 best English-language novels of the 20th century. The present research focuses on stream of consciousness technique used by William Faulkner’s novel “The Sound and Fury”. -

2.3 Flash-Forward: the Future Is Now

2.3 Flash-Forward: The Future is Now BY PATRICIA PISTERS 1. The Death of the Image is Behind Us Starting with the observation that “a certain idea of fate and a certain idea of the image are tied up in the apocalyptic discourse of today’s cultural climate,” Jacques Rancière investigates the possibilities of “imageness,” or the future of the image that can be an alternative to the often-heard complaint in contemporary culture that there is nothing but images, and that therefore images are devoid of content or meaning (1). This discourse is particularly strong in discussions on the fate of cinema in the digital age, where it is commonly argued that the cinematographic image has died either because image culture has become saturated with interactive images, as Peter Greenaway argues on countless occasions, or because the digital has undermined the ontological photographic power of the image but that film has a virtual afterlife as either information or art (Rodowick 143). Looking for the artistic power of the image, Rancière offers in his own way an alternative to these claims of the “death of the image.” According to him, the end of the image is long behind us. It was announced in the modernist artistic discourses that took place between Symbolism and Constructivism between the 1880s and 1920s. Rancière argues that the modernist search for a pure image is now replaced by a kind of impure image regime typical for contemporary media culture. | 1 2.3 Flash-Forward: The Future is Now Rancière’s position is free from any technological determinism when he argues that there is no “mediatic” or “mediumistic” catastrophe (such as the loss of chemical imprinting at the arrival of the digital) that marks the end of the image (18). -

Writing Steps

PREWRITING ● gather your thoughts and ideas ○ read, research, interview, experience, discuss, reflect ○ brainstorm, list, journal, freewrite, cluster ● direct your writing ○ determine your purpose (what you want your paper to do) ○ focus and direct your ideas to address your purpose ○ topic, thesis, capsule summary ● tailor your writing ○ determine your audience ○ choose vocabulary, syntax, formality, appeal, organization, approach ○ capture essence and flavor of paper ● plan your writing ○ organize your ideas into an outline or plan ○ chronological, spatial, topical, priority ○ inductive (exploratory), deductive (argumentative) DRAFTING ● get situated ○ comfortable, stimulating, no distractions ● express your ideas without worrying about mechanical details ○ let thoughts flow ○ do not struggle with words, spelling, punctuation, other details ○ do not follow urge to reread, restructure, rewrite ○ write quickly, informally ○ concentrate on main ideas and message ● stick to subject ○ avoid digression into interesting examples ○ follow outline or plan (with minor modifications) ○ use transitions to connect and show relationships between and among ideas ● write draft in one sitting ○ consistent tone, smooth continuity ● consider writing a second, independent draft ○ compare the independent drafts and pull out best parts of each ● take a break when your draft is complete REVISING ● re-envision what you have written ○ ensure your paper fulfills its purpose (what you want the paper to do) ○ consider alternative ways to more effectively, efficiently -

ELEMENTS of FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms That Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction

Dr. Hallett ELEMENTS OF FICTION – NARRATOR / NARRATIVE VOICE Fundamental Literary Terms that Indentify Components of Narratives “Fiction” is defined as any imaginative re-creation of life in prose narrative form. All fiction is a falsehood of sorts because it relates events that never actually happened to people (characters) who never existed, at least not in the manner portrayed in the stories. However, fiction writers aim at creating “legitimate untruths,” since they seek to demonstrate meaningful insights into the human condition. Therefore, fiction is “untrue” in the absolute sense, but true in the universal sense. Critical Thinking – analysis of any work of literature – requires a thorough investigation of the “who, where, when, what, why, etc.” of the work. Narrator / Narrative Voice Guiding Question: Who is telling the story? …What is the … Narrative Point of View is the perspective from which the events in the story are observed and recounted. To determine the point of view, identify who is telling the story, that is, the viewer through whose eyes the readers see the action (the narrator). Consider these aspects: A. Pronoun p-o-v: First (I, We)/Second (You)/Third Person narrator (He, She, It, They] B. Narrator’s degree of Omniscience [Full, Limited, Partial, None]* C. Narrator’s degree of Objectivity [Complete, None, Some (Editorial?), Ironic]* D. Narrator’s “Un/Reliability” * The Third Person (therefore, apparently Objective) Totally Omniscient (fly-on-the-wall) Narrator is the classic narrative point of view through which a disembodied narrative voice (not that of a participant in the events) knows everything (omniscient) recounts the events, introduces the characters, reports dialogue and thoughts, and all details. -

Stream of Consciousness Technique: Psychological Perspectives and Use in Modern Novel المنظور النفسي واستخدا

Stream of Consciousness Technique: Psychological Perspectives and Use in Modern Novel Weam Majeed Alkhafaji Sajedeh Asna'ashari University of Kufa, College of Education Candle & Fog Publishing Company Email: [email protected] Email: [email protected] Abstract Stream of Consciousness technique has a great impact on writing literary texts in the modern age. This technique was broadly used in the late of nineteen century as a result of thedecay of plot, especially in novel writing. Novelists began to use stream of consciousness technique as a new phenomenon, because it goes deeper into the human mind and soul through involving it in writing. Modern novel has changed after Victorian age from the traditional novel that considers themes of religion, culture, social matters, etc. to be a group of irregular events and thoughts interrogate or reveal the inner feeling of readers. This study simplifies stream of consciousness technique through clarifying the three levels of conscious (Consciousness, Precociousness and Unconsciousness)as well as the subconsciousness, based on Sigmund Freud theory. It also sheds a light on the relationship between stream of consciousness, interior monologue, soliloquy and collective unconscious. Finally, This paper explains the beneficial aspects of the stream of consciousness technique in our daily life. It shows how this technique can releaseour feelings and emotions, as well as free our mind from the pressure of thoughts that are upsetting our mind . Key words: Stream of Consciousness, Modern novel, Consciousness, Precociousness and Unconsciousness and subconsciousness. تقنية انسياب اﻻفكار : المنظور النفسي واستخدامه في الرواية الحديثة وئام مجيد الخفاجي ساجدة اثنى عشري جامعة الكوفة – كلية التربية – قسم اللغة اﻻنكليزية دار نشر كاندل وفوك الخﻻصة ان لتقنية انسياب اﻻفكار تأثير كبير على كتابة النصوص اﻻدبية في العصر الحديث. -

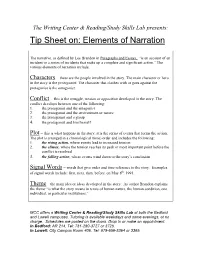

Elements of Narration

The Writing Center & Reading/Study Skills Lab presents: Tip Sheet on: Elements of Narration The narrative, as defined by Lee Brandon in Paragraphs and Essays, “is an account of an incident or a series of incidents that make up a complete and significant action.” The various elements of narration include: Characters – these are the people involved in the story. The main character or hero in the story is the protagonist. The character that clashes with or goes against the protagonist is the antagonist. Conflict – this is the struggle, tension or opposition developed in the story. The conflict develops between one of the following: 1. the protagonist and the antagonist 2. the protagonist and the environment or nature 3. the protagonist and a group 4. the protagonist and him/herself Plot – this is what happens in the story; it is the series of events that forms the action. The plot is arranged in a chronological (time) order and includes the following: 1. the rising action, where events lead to increased tension 2. the climax, where the tension reaches its peak or most important point before the conflict is resolved 3. the falling action, where events wind down to the story’s conclusion Signal Words – words that give order and time reference to the story. Examples of signal words include: first, next, then, before, on May 8th, 1991. Theme – the main idea or ideas developed in the story. As author Brandon explains, the theme “is what the story means in terms of human nature, the human condition, one individual, or particular institutions.” MCC offers a Writing Center & Reading/Study Skills Lab at both the Bedford and Lowell campuses. -

Philosophy of Action and Theory of Narrative1

PHILOSOPHY OF ACTION AND THEORY OF NARRATIVE1 TEUN A. VAN DIJK 1. INTRODUCTION 1.1. The aim of this paper is to apply some recent results from the philosophy of action in the theory of narrative. The intuitive idea is that narrative discourse may be conceived of as a form of natural action description, whereas a philosophy or, more specifically, a logic of action attempts to provide formal action descriptions. It is expected that, on the one hand, narrative discourse is an interesting empirical testing ground for the theory of action, and that, on the other hand, formal action description may yield insight into the abstract structures of narratives in natural language. It is the latter aspect of this interdisciplinary inquiry which will be em- phasized in this paper. 1.2. If there is one branch of analytical philosophy which has received particular at- tention in the last ten years it certainly is the philosophy of action. Issued from classical discussions in philosophical psychology (Hobbes, Hume) the present analy- sis of action finds applications in the foundations of the social sciences, 2 in ethics 3 1This paper has issued from a seminar held at the University of Amsterdam in early 1974. Some of the ideas developed in it have been discussed in lectures given at the Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes (Paris), Louvain, Bielefeld, Münster, Ann Arbor, CUNY (New York) and Ant- werp, in 1973 and 1974. A shorter version of this paper has been published as Action, Action Description and Narrative in New literary history 6 (1975): 273-294. -

Distinguishing Narration and Speech in Prose Fiction Dialogues

Distinguishing Narration and Speech in Prose Fiction Dialogues Adam Eky and Mats Wirén Stockholm University, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden {adam.ek, mats.wiren}@ling.su.se Abstract. This paper presents a supervised method for a novel task, namely, detecting elements of narration in passages of dialogue in prose fiction. The method achieves an F1-score of 80.8%, exceeding the best baseline by almost 33 percentage points. The purpose of the method is to enable a more fine-grained analysis of fictional dialogue than has previously been possible, and to provide a component for the further analysis of narrative structure in general. Keywords: Prose fiction · Literary dialogue · Characters’ discourse · Narrative structure 1 Introduction Prose fiction typically consists of passages alternating between two levels of narrative transmission: the narrator’s telling of the story to a narratee, and the characters’ speaking to each other in that story (mediated by the narrator). As stated in [Dolezel, 1973], quoted in [Jahn, 2017, Section N8.1]: "Every narrative text T is a concatenation and alternation of ND [narrator’s discourse] and CD [characters’ discourse]". An example of this alternation can be found in August Strindberg’s The Red Room (1879), with our annotation added to it: (1) <NARRATOR> Olle very skilfully made a bag of one of the sheets and stuffed everything into it, while Lundell went on eagerly protesting. When the parcel was made, Olle took it under his arm, buttoned his ragged coat so as to hide the absence of a waistcoat, and set out on his way to the town. -

143 the Flashforward Facility at DESY Abstract 1. Introduction

DESY 15-143 The FLASHForward Facility at DESY A. Aschikhin1, C. Behrens1, S. Bohlen1, J. Dale1, N. Delbos2, L. di Lucchio1, E. Elsen1, J.-H. Erbe1, M. Felber1, B. Foster3,4,*, L. Goldberg1, J. Grebenyuk1, J.-N. Gruse1, B. Hidding3,5, Zhanghu Hu1, S. Karstensen1, A. Knetsch3, O. Kononenko1, V. Libov1, K. Ludwig1, A. R. Maier2, A. Martinez de la Ossa3, T. Mehrling1, C. A. J. Palmer1, F. Pannek1, L. Schaper1, H. Schlarb1, B. Schmidt1, S. Schreiber1, J.-P. Schwinkendorf1, H. Steel1,6, M. Streeter1, G. Tauscher1, V. Wacker1, S. Weichert1, S. Wunderlich1, J. Zemella1, J. Osterhoff1 1 Deutsches Elektronen-Synchrotron (DESY), Notkestrasse 85, 22607 Hamburg, Germany 2 Center for Free-Electron Laser Science & Department of Physics, University of Hamburg, Luruper Chaussee 149, 22761 Hamburg, Germany 3 Department of Physics, University of Hamburg, Luruper Chaussee 149, 22761 Hamburg, Germany 4 also at DESY and University of Oxford, UK 5 also at University of Strathclyde, UK 6 also at University of Sydney, Australia * Corresponding author Abstract The FLASHForward project at DESY is a pioneering plasma-wakefield acceleration experiment that aims to produce, in a few centimetres of ionised hydrogen, beams with energy of order GeV that are of quality sufficient to be used in a free-electron laser. The plasma wave will be driven by high- current density electron beams from the FLASH linear accelerator and will explore both external and internal witness-beam injection techniques. The plasma is created by ionising a gas in a gas cell with a multi-TW laser system, which can also be used to provide optical diagnostics of the plasma and electron beams due to the <30 fs synchronisation between the laser and the driving electron beam.