PROGRAM NOTES Wolfgang Mozart Symphony No. 25 in G Minor, K

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bärenreiter Organ Music

>|NAJNAEPAN KNC=JIQOE? .,-.+.,-/ 1 CONTENTS Organ Music Solo Voice and Organ ...............30 Index by Collections and Series ...........4–13 Books............................................... 31 Edition Numbers ....................... 34 Composers ....................................14 Contemporary Music Index by Jazz .............................................. 29 A Selection ..............................32 Composers / Collections .........35 Transcriptions for Organ .........29 Photo: Edition Paavo Blåfi eld ABBREVIATIONS AND KEY TO FIGURES Ed. Editor Contents Ger German text Review Eng English text Content valid as of May 2012. Bärenreiter-Verlag Fr French text Errors excepted and delivery terms Karl Vötterle GmbH & Co. KG Lat Latin text subject to change without notice. International Department BA Bärenreiter Edition P.O. Box 10 03 29 H Bärenreiter Praha Cover design with a photograph D-34003 Kassel · Germany SM Süddeutscher Musikverlag by Edition Paavo Blåfi eld. Series E-Mail: paavo@blofi eld.de www.baerenreiter.com a.o. and others www.blofi eld.de E-Mail: [email protected] Printed in Germany 3/1206/10 · SPA 238 2 Discover Bärenreiter … www.baerenreiter.com Improved Functionality Simple navigation enables quick orientation Clear presentation Improved Search Facility Comprehensive product information User-friendly searches by means of keywords Product recommendations Focus A new area where current themes are presented in detail … the new website3 ORGAN Collections and Series Enjoy the Organ Ave Maria, gratia plena Ave-Maria settings The new series of easily playable pieces for solo voice and organ (Lat) BA 8250 page 30 Enjoy the Organ I contains a collection of stylistically varied Bärenreiter Organ Albums pieces for amateur organists Collections of organ pieces which are equally suitable for page 6-7 use in church services and in concerts. -

DVOŘÁK's CHAMBER and PIANO MUSIC in Preparation in High-Standard Reprints

Titles DVOŘÁK'S CHAMBER AND PIANO MUSIC in preparation in high-standard reprints Serenade in D minor Op. 44 Our publishing house's lasting care for quality sheet Piano four hands BA 9565 From the Bohemian Forest Op. 68 for wind instruments, violoncello and double bass music of this most-performed classic Czech composer is Edited by Robin Tait BA 9547, BA 9548 Slavonic Dances Op. 46 and Op. 72 BA 10424 score also re ected in a new series of reprints of mostly chamber BA 10424-22 parts in slipcover and piano music from the Antonín Dvořák Complete Violin and Piano To appear in September 2016 BA 9576 Romantic Pieces Op. 75 DVOŘÁK Edition (ADCE), prepared by the best Czech editors The new Urtext edition of this masterpiece of its genre and Dvořák specialists of the day (Jarmil Burghauser, B Ä R E N R E I T E R U R T E X T is based jointly on the autograph and the ¦ rst Simrock Piano Trio / Quartet / Quintet BA 9578 Piano Trio in B- at major Op. 21 edition (1879). The editor revised the editorial decisions Antonín Čubr, Antonín Pokorný, Karel Šolc, František To appear in May 2016 made in the 1879 print, restoring some of Dvořák's Bartoš, etc.). With their combination of modern printing BA 9564 Piano Trio in F minor Op. 65 original ideas and clarifying certain inconsistencies BA 9538 Piano Trio in G minor Op. 26 in articulation. The current edition contains a critical and Bärenreiter-brand quality, the ADCE reprints re ect BA 9537 Piano Quartet in E- at major Op. -

LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart

CONCERT #5 - Released February 17, 2021 LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN Sonata No. 6 for Violin and Piano in A Major, Op. 30, No. 1 Allegro Adagio molto espressivo Allegretto con variazioni Amy Schwartz Moretti violin / Orion Weiss piano WOLFgang AMADEUS MOZART Quartet for Piano and Strings in G minor, K. 478 Allegro Andante Rondo Benjamin Bowman violin /Jonathan Vinocour viola / Edward Arron cello / Jeewon Park piano LUDWIG VAN BEETHOVEN frequently alternates between excited episodes and (1770-1827) moments of quiet reflection. The main theme is built Sonata No. 6 for Violin and Piano in A Major, from a series of rising intervals. A brief coda ends it Op. 30, No. 1 (1802) peacefully. Most recent SCMS performance: Summer 2011 In triple meter the Adagio, molto espressivo opens Enjoying early fame as both pianist and composer, with a floating violin line over gently coaxing the year 1802 threatened Beethoven’s prospects for rhythmic thrusts on the piano. As if to stress the ongoing success. Attempts to secure a court position importance of the violin the piano supports the failed to materialize. Worst of all, his deepening bowed instrument’s expressive long-breathed deafness and attendant despair began to isolate him melodies with understated prodding alternating from the world around him. with simple arpeggios. It is the piano, however, that has the final, albeit softly spoken, word at the In October came his famous lament, the movement’s end. Heiligenstadt Testament, a letter he wrote but never sent to his brothers wherein he expressed In its initial form, Beethoven provided an energetic his terrible anguish and doubt, and admitted to and virtuosic finale before replacing it with an thoughts of suicide. -

Performances from 1974 to 2020

Performances from 1974 to 2020 2019-20 December 1 & 2, 2018 Michael Slon, Conductor September 28 & 29, 2019 Family Holiday Concerts Benjamin Rous, Conductor MOZART Symphony No. 32 February 16 & 17, 2019 ROUSTOM Ramal Benjamin Rous, Conductor BRAHMS Piano Concerto No. 2 in B-flat Major RAVEL Pavane pour une infante défunte RAVEL Piano Concerto in G Major November 16 & 17, 2019 MOYA Siempre Lunes, Siempre Marzo Benjamin Rous & Michael Slon, Conductors KODALY Variations on a HunGarian FolksonG MONTGOMERY Caught by the Wind ‘The Peacock’ RICHARD STRAUSS Horn Concerto No. 1 in E-flat Major March 23 & 24, 2019 MENDELSSOHN Psalm 42 Benjamin Rous, Conductor BRUCKNER Te Deum in C Major BARTOK Violin Concerto No. 2 MENDELSSOHN Symphony No. 4 in A Major December 6 & 7, 2019 Michael Slon, Conductor April 27 & 28, 2019 Family Holiday Concerts Benjamin Rous, Conductor WAGNER Prelude from Parsifal February 15 & 16, 2020 SCHUMANN Piano Concerto in A minor Benjamin Rous, Conductor SHATIN PipinG the Earth BUTTERWORTH A Shropshire Lad RESPIGHI Pines of Rome BRITTEN Nocturne GRACE WILLIAMS Elegy for String Orchestra June 1, 2019 VAUGHAN WILLIAMS On Wenlock Edge Benjamin Rous, Conductor ARNOLD Tam o’Shanter Overture Pops at the Paramount 2018-19 2017-18 September 29 & 30, 2018 September 23 & 24, 2017 Benjamin Rous, Conductor Benjamin Rous, Conductor BOWEN Concerto in C minor for Viola WALKER Lyric for StrinGs and Orchestra ADAMS Short Ride in a Fast Machine MUSGRAVE SonG of the Enchanter MOZART Clarinet Concerto in A Major SIBELIUS Symphony No. 2 in D Major BEETHOVEN Symphony No. 7 in A Major November 17 & 18, 2018 October 6, 2017 Damon Gupton, Conductor Michael Slon, Conductor ROSSINI Overture to Semiramide UVA Bicentennial Celebration BARBER Violin Concerto WALKER Lyric for StrinGs TCHAIKOVSKY Symphony No. -

The Classical Period

The Classical Period 1750-1820 (1825) 1 Historical Themes Industrial Revolution Age of Enlightenment Violent political and social upheaval Culture 2 Industrial Revolution Steam engine changed the nature of European life Move to a more urban society Time of great growth and economic prosperity 3 Age of Enlightenment Emphasis on the natural rights of people Ability of humans to shape their own environment All established ideas were being reexamined, including the existence of God. 4 Violent political & social upheaval Seven Years’ War American Revolution French Revolution Napoleonic Wars Power shifted from aristocracy and church to the middle class Social mobility increased 5 Culture France was the leading cultural center of the continent (esp. fashion-Paris) Austria (Vienna) & Germany were the centers of musical growth Improved economic conditions led to more people seeking “luxury” Music was viewed as “an innocent luxury” Demand for new compositions was great 6 The Classical Style 7 Characteristics Contrast of Mood Rhythm Simpler textures Simpler melodies Dynamics 8 Contrast of Mood Large thematic and tonal contrasts unlike the single-mood compositions of the Baroque Dramatic, turbulent might lead to carefree, dance-like Change could be sudden or gradual 9 Rhythm Flexibility of rhythm adds variety Many rhythmic patterns unlike repetitive rhythms of the Baroque Unexpected pauses, syncopations, frequent changes from long notes to shorter notes Change could be sudden or gradual 10 Simpler textures Homophonic unlike the polyphony of the late Baroque Change from one texture to the next could be sudden or gradual 11 Simpler melodies Tuneful, easy to remember unlike the complex, ornamented melodies of the Baroque Mozart-“Twinkle, Twinkle, Little Star” Melodies were balanced and symmetrical (2 phrases of same length) like “Mary Had a Little Lamb” 12 Dynamics Expressing shades of emotions led to gradual dynamic changes Crescendo and decrescendo vs. -

PROGRAM NOTES Wolfgang Mozart Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K

PROGRAM NOTES by Phillip Huscher Wolfgang Mozart Born January 27, 1756, Salzburg, Austria. Died December 5, 1791, Vienna, Austria. Symphony No. 40 in G Minor, K. 550 Mozart entered this symphony in his catalog on July 25, 1788. The date of the first performance is not known. At these concerts, Trevor Pinnock conducts Mozart’s revision of the score, adding a pair of clarinets to the original version, which calls for one flute, two oboes, two bassoons, two horns, and strings. Performance time is approximately twenty-six minutes. The Chicago Symphony Orchestra’s first subscription concert performances of Mozart’s Fortieth Symphony were given at the Auditorium Theatre on November 18 and 19, 1892, with Theodore Thomas conducting. Our most recent subscription concert performances were given at Orchestra Hall on February 2, 4, and 5, 1995, with Zubin Mehta conducting. The Orchestra first performed this symphony at the Ravinia Festival on July 8, 1938, with Artur Rodzinksi conducting, and most recently on June 29, 2000, with Pinchas Zukerman conducting. Ironically, it is Mozart’s last three symphonies rather than the famous requiem that remain the mystery of his final years. Almost as soon as Mozart died, romantic myth attached itself to the unfinished pages of the requiem left scattered on his bed; a host of questions—who commissioned the work?; who finished it?; was Mozart poisoned?—inspired painters, novelists, biographers, librettists, playwrights, and screenwriters to heights of imaginative re-creation. We now know those answers: the requiem is unfinished, but not unexplained. The final symphonies, on the other hand—no. -

Program Notes | All Tchaikovsky

23 Season 2018-2019 Thursday, January 31, at 7:30 The Philadelphia Orchestra Friday, February 1, at 2:00 Saturday, February 2, at 8:00 Kensho Watanabe Conductor Edgar Moreau Cello Tchaikovsky Capriccio italien, Op. 45 Tchaikovsky Variations on a Rococo Theme, Op. 33, for cello and orchestra Intermission Tchaikovsky Symphony No. 1 in G minor, Op. 13 (“Winter Daydreams”) I. Allegro tranquillo (Dreams of a Winter Journey) II. Adagio cantabile ma non tanto (Land of Desolation, Land of Mists) III. Scherzo: Allegro scherzando giocoso IV. Finale: Andante lugubre—Allegro moderato—Allegro maestoso—Andante lugubre—Allegro vivo This program runs approximately 1 hour, 50 minutes. LiveNote® 2.0, the Orchestra’s interactive concert guide for mobile devices, will be enabled for these performances. The January 31 concert is sponsored by Jack and Ramona Vosbikian. The February 2 concert is sponsored by Ms. Elaine Woo Camarda. Philadelphia Orchestra concerts are broadcast on WRTI 90.1 FM on Sunday afternoons at 1 PM, and are repeated on Monday evenings at 7 PM on WRTI HD 2. Visit www.wrti.org to listen live or for more details. 24 ® Getting Started with LiveNote 2.0 » Please silence your phone ringer. » Make sure you are connected to the internet via a Wi-Fi or cellular connection. » Download the Philadelphia Orchestra app from the Apple App Store or Google Play Store. » Once downloaded open the Philadelphia Orchestra app. » Tap “OPEN” on the Philadelphia Orchestra concert you are attending. » Tap the “LIVE” red circle. The app will now automatically advance slides as the live concert progresses. -

131 with G in the Bass, Shown Below in Example 4.9. As with the G Minor

with G in the bass, shown below in Example 4.9. As with the G minor that never arrived, C minor would have been closely related to the home key. This time, however, it would have been as its submediant instead of its mediant. Finally, landing on C minor instead of C major would have avoided the enharmonic paradox on pitch-class 4. Beginning of B section mm. 32 – 33 c: VI V11 I C minor anticipated C major arrives (A¼ and E¼) Example 4.9 Poulenc, Piano Concerto, second movement, first part of B section, mm. 32–33, anticipation of the minor mode and unexpected arrival of C major The primary key areas of this first part of the B section, C major, E major, and A¼ major, are summarized in Example 4.10. The keys tonicized for a shorter duration, shown as quarter notes, are included to show relationships with the main keys. Justification for relating C major back to G major, instead of giving it its own major- minor complex, will be given below. 131 B section (part 1): Mm. 33 35 37 40 45 46 transition first theme 1 2 E¼/e¼: (key of IV or iv……………..........) G/g: IV A¼/a¼: ii i VI i I Example 4.10 Poulenc, Piano Concerto, second movement, key relations in the first part of the B section Parallel modes and the chromatic mediants they support thwart expectations and emerge as the main point of tension for the entire movement. The second half of the B section has the loudest dynamics in the movement thus far, with fortissimo and fortississimo entrances of the theme, double-dotted rhythms, flights into the high registers in the solo part, and frequent harmonic moves to remote keys. -

Knox Music Program- Major Works List Updated December 2019

KNOX MUSIC PROGRAM - MAJOR WORKS REPERTOIRE LIST (UPDATED DECEMBER 2019) Johann Georg Albrechtsberger Organ Concerto in B-flat Major - 2011 Johann Sebastian Bach Cantata BWV 4, Christ lag in Todesbanden - 1985, 2011 Cantata BWV 63, Christen, ätzet diesen Tag - 2010 Cantata BWV 106, Gottes Zeit ist die allerbeste Zeit - 1985, 1987 Cantata BWV 140, Wachet auf, ruft uns die Stimme – 1983 Cantata BWV 191 Gloria in Excelsis - 2016 Johannes-Passion (St. John Passion), BWV 245 - 1984, 1990, 1995, 2001, 2010 Magnificat, BWV 243 - 1993, 2006, 2017 Mass in B Minor, BWV 232 - 1992, 1996 Matthäus-Passion (St. Matthew Passion), BWV 244 - 1987, 1994, 2002 Missa brevis in F Major, BWV 233 - 1997, 2000, 2004, 2017 Missa brevis in A Major, BWV 234 - 1997, 2000, 2008, 2015, 2019 Missa brevis in G Minor, BWV 235 - 1998, 2009, 2014, 2018 Missa brevis in G Major, BWV 236 - 1998, 2013, 2016 Oster-Oratorium (Easter Oratorio), BWV 249 - 2005 Weihnachts-Oratorium (Christmas Oratorio), BWV 248 (complete) - 1985, 1988, 1992, 2011, 2019 Weihnachts-Oratorium, BWV 248 (portions) – 1997 (Parts I, IV and V), 2005 (Parts IV, V, and VI), 2007 (I, II, and III), 2014 (Parts I, V, and VI), 2016 (Part I, excerpts) Ludwig van Beethoven Mass in C Major, Op. 86 - 1989, 2003 Hector Berlioz L’enfance du Christ (The Infant Christ), Op. 25 - 1998, 2012 Te Deum, Op. 22 - 1983 Judith Bingham Jacob’s Ladder: Parable for Organ and Strings - 2009 Johannes Brahms Ein deutsches Requiem (A German Requiem), Op. 45 - 2000 Benjamin Britten Saint Nicolas Cantata, Op. 42 - 1990, 2008 Marc-Antoine Charpentier Messe de Minuit pour Noël (Midnight Mass for Christmas) (excerpts) – 2009, 2016 1 Michel Corrette Organ Concerto No. -

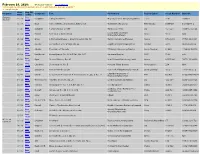

Sunday Playlist

February 16, 2020: (Full-page version) Close Window “There was no one near to confuse me, so I was forced to become original.” — Joseph Haydn Start Buy CD Program Composer Title Performers Record Label Stock Number Barcode Time online Sleepers, Buy 00:01 Corigliano Lullaby for Natalie Meyers/London Symphony/Slatkin e one 7791 099923 Awake! Now! Buy 00:07 Bach Cello Suite No. 2 in D minor, BWV 1008 Mstislav Rostropovich EMI Classics 55364/5 D 273269-1 Now! Buy 00:30 Schubert 4 Impromptus, D. 899 Maria Joao Pires DG 457 550 028945755021 Now! Buy Los Angeles Chamber 01:01 Handel Suite in G ~ Water Music Delos 3010 N/A Now! Orchestra/Schwarz Buy 01:12 Grieg 3 Orchestral Pieces ~ Sigurd Jorsalfar, Op. 56 Malmö Symphony/Engeset Naxos 8.508015 747313801534 Now! Buy 01:30 Dvorak Serenade in E for Strings, Op.22 English String Orch/Boughton Nimbus 5016 08360350162 Now! Buy 02:00 Sibelius The Swan of Tuonela Pittsburgh Symphony/Maazel Sony Classical 61963 074646196328 Now! Buy 02:13 Beethoven String Quartet No. 12 in E flat, Op. 127 Smetana Quartet PCM 7063 n/a Now! Buy 02:50 Elgar Dream Children, Op. 43 New Zealand Symphony/Judd Naxos 8.557166 747313216628 Now! Buy 03:00 Chadwick String Quartet No. 5 Portland String Quartet Northeastern 234 N/A Now! Buy 03:34 Strauss Jr. Roses from the South New York Philharmonic/Bernstein Sony Classical 46710 07464467102 Now! Buy Chamber Orchestra of 03:47 Vivaldi Concerto in B minor for 4 Violins and Cello, Op. 3 No. 10 EMI 69143 5099976914324 Now! Toulouse/Auriacombe Buy 04:01 Mendelssohn Hebrides Overture, Op. -

How to Prepare for the Music Fundamentals Test

How to Prepare for the Music Fundamentals Test On your audition day, you will be given a brief written music fundamentals test. Its purpose is to determine whether or not you are ready to begin Music Theory I and Aural Skills I during your first semester at Wheaton. The test is graded pass/fail, and both accuracy and time are factored into the results. Even if you have already taken music theory or aural skills classes, the test is mandatory. To prepare for the test, memorize the following: • Note names in both treble and bass clefs. • The relationships between basic note values (i.e., whole notes, half notes, quarter notes, 8th notes, and 16th notes), as well as their equivalent rests. • The meanings of dots, ties, and beams. • The meanings of 2/4, 3/4, 4/4 (C), 6/8, 9/8 and 12/8 signatures. • All 30 major and natural minor scales in treble and bass clefs. • All 30 major and minor key signatures in treble and bass clefs. If you are unfamiliar with any of the concepts listed above, desire clarification on them, or want to practice them, you are encouraged to visit the following websites: www.musictheory.net www.teoria.com www.emusictheory.com Revised April 2012 Scale and Key Signature Memorization Guide Major Scale Natural Minor Scale Key Signature C♭ Major C♭ D♭ E♭ F♭ G♭ A♭ B♭ C♭ A♭ Minor A♭ B♭ C♭ D♭ E♭ F♭ G♭ A♭ G♭ Major G♭ A♭ B♭ C♭ D♭ E♭ F G♭ E♭ Minor E♭ F G♭ A♭ B♭ C♭ D♭ E♭ D♭ Major D♭ E♭ F G♭ A♭ B♭ C D♭ B♭ Minor B♭ C D♭ E♭ F G♭ A♭ B♭ A♭ Major A♭ B♭ C D♭ E♭ F G A♭ F Minor F G A♭ B♭ C D♭ E♭ F E♭ Major E♭ F G A♭ B♭ C D E♭ C Minor C D -

P. I. Tchaikovsky Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 35

P. I. Tchaikovsky Concerto for violin and orchestra, op. 35 By Marina Popovic Supervisor Per Kjetil Farstad This Master’s Thesis is carried out as a part of the education at the University of Agder and is therefore approved as a part of this education. However, this does not imply that the University answers for the methods that are used or the conclusions that are drawn. University of Agder, 2012 Faculty of Fine Arts Department of Music 2 Acknowledgments I have to admit that studying in Norway was tough occasionally, but I fill the need to express special thanks to persons that made it much possible. I use this opportunity to thank my parents for the longest support in my carrier. Even though I owe gratitude to all my teachers and professors; special thanks go to my professors at University of Agder: Per Kjetil Farstad, Tønsberg, Knut, Adam Grüchot, Terje Howard Mathisen, Tellef Juva, Bård Monsen and Trygve Trædal. Also, I want to express thankfulness to my fellow students Rade Zivanovic, Jelena Adamovic, Stevan Sretenovic, Nikola Markovic, Svetlana Jelic and Andrej Miletic for both critics and support during our mutual work. Last, but of the significant importance my acknowledgment goes to libraries of University of Agder and Faculty of Music, Belgrade. 3 Contents Acknowledgements ............................................................................................................ 3 Contents .............................................................................................................................. 4 Introduction