Reading Chapter

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

100 Most Influential Black Christian History-Makers

100 Most Influential Black Christian History-Makers Black history is important, but making history now is more important. Compiled and Edited by the Editors of BCNN1.com Black Christian News Network One We thank God for Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and Rosa Parks, but we need a Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and a Rosa Parks today. Introduction We believe that black history is important. But we also believe that making history today is more important. We cannot rest on the laurels of great luminaries such as Frederick Douglass, Martin Luther King, Jr., Rosa Parks, George Washington Carver, and others. God used these and others mightily in their time; now He has given us this time and we will have to answer to Him as to how we use it. In light of that, we have attempted to place in one volume the most influential Black Christian History-Makers who are living today and who are serving Jesus Christ with their various gifts and talents. The ability to lead is not something you can train to have. True leadership is a gift from God that is undeniable by people. You cannot make yourself a leader of people. In other words, you cannot be a leader just because you want to be. Only God makes leaders. One can improve his or her leadership abilities but one cannot make himself or herself a leader. The people who have been chosen for this list are not people who are trying to be leaders; they were born leaders by the grace of God. -

Praise & Worship

pg0144_Layout 1 4/4/2017 1:07 PM Page 44 Soundtracks! H ot New Artist! pages 24–27 ease! ew Rele page N 43 More than 10,000 CDs and 186,000 Music Downloads available at Christianbook.com! page 8 1–800–CHRISTIAN (1-800-247-4784) pg0203_Layout 1 4/4/2017 1:07 PM Page 2 NEW! Elvis Presley Joey Feek NEW! Crying in If Not for You the Chapel Showcasing some of the Celebrating Elvis’s commitment first songs Joey Feek ever to his faith, this newly compiled recorded, this album in- collection features “His Hand cludes “That’s Important to in Mine,” “How Great Thou Art,” Me,” “Strong Enough to Cry,” “Peace in the Valley,” “He “Nothing to Remember,” Touched Me,” “Amaz ing Grace,” “The Cowboy’s Mine,” and more. “Southern Girl,” and more. WRCD31415 Retail $9.99 . .CBD $8.99 WRCD34415 Retail $11.99 . .CBD $9.99 Also available: WR933623 If Not for You—Book and CD . 15.99 14.99 David Phelps NEW! Hymnal Deal! Phelps’s flawless tenor inter- pretations will lift your appre- Joey+Rory Hymns That Are ciation of favorite hymns to a whole new level! Features “In Important to Us the Garden,” “How Great Thou The beloved country duo Art,” “Battle Hymn of the Re- sings their favorite hymns! public,” and more. Includes “I Need Thee Every Hour,” “He Touched WRCD32200 Retail $13.99 . .CBD $11.99 Me,” “I Surrender All,” “The Also available: Old Rugged Cross,” “How WRCD49082 Freedom . 13.99 11.99 WR918393 Freedom—DVD . 19.99 15.99 Great Thou Art,” and more. -

Chance the Rapper's Creation of a New Community of Christian

Bates College SCARAB Honors Theses Capstone Projects 5-2020 “Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book Samuel Patrick Glenn [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses Recommended Citation Glenn, Samuel Patrick, "“Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book" (2020). Honors Theses. 336. https://scarab.bates.edu/honorstheses/336 This Open Access is brought to you for free and open access by the Capstone Projects at SCARAB. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors Theses by an authorized administrator of SCARAB. For more information, please contact [email protected]. “Your Favorite Rapper’s a Christian Rapper”: Chance the Rapper’s Creation of a New Community of Christian Hip Hop Through His Use of Religious Discourse on the 2016 Mixtape Coloring Book An Honors Thesis Presented to The Faculty of the Religious Studies Department Bates College in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Bachelor of Arts By Samuel Patrick Glenn Lewiston, Maine March 30 2020 Acknowledgements I would first like to acknowledge my thesis advisor, Professor Marcus Bruce, for his never-ending support, interest, and positivity in this project. You have supported me through the lows and the highs. You have endlessly made sacrifices for myself and this project and I cannot express my thanks enough. -

Pg0140 Layout 1

New Releases HILLSONG UNITED: LIVE IN MIAMI Table of Contents Giving voice to a generation pas- Accompaniment Tracks . .14, 15 sionate about God, the modern Bargains . .20, 21, 38 rock praise & worship band shares 22 tracks recorded live on their Collections . .2–4, 18, 19, 22–27, sold-out Aftermath Tour. Includes 31–33, 35, 36, 38, 39 the radio single “Search My Heart,” “Break Free,” “Mighty to Save,” Contemporary & Pop . .6–9, back cover “Rhythms of Grace,” “From the Folios & Songbooks . .16, 17 Inside Out,” “Your Name High,” “Take It All,” “With Everything,” and the Gifts . .back cover tour theme song. Two CDs. Hymns . .26, 27 $ 99 KTCD23395 Retail $14.99 . .CBD Price12 Inspirational . .22, 23 Also available: Instrumental . .24, 25 KTCD28897 Deluxe CD . 19.99 15.99 KT623598 DVD . 14.99 12.99 Kids’ Music . .18, 19 Movie DVDs . .A1–A36 he spring and summer months are often New Releases . .2–5 Tpacked with holidays, graduations, celebra- Praise & Worship . .32–37 tions—you name it! So we had you and all your upcoming gift-giving needs in mind when we Rock & Alternative . .10–13 picked the products to feature on these pages. Southern Gospel, Country & Bluegrass . .28–31 You’ll find $5 bargains on many of our best-sell- WOW . .39 ing albums (pages 20 & 21) and 2-CD sets (page Search our entire music and film inventory 38). Give the special grad in yourConGRADulations! life something unique and enjoyable with the by artist, title, or topic at Christianbook.com! Class of 2012 gift set on the back cover. -

Trip Lee 20/20 Review

Trip lee 20/20 review Ever since I listened to Trip Lee's guest spot on Lecrae's "Jesus Muzik," I knew I'd heard a new entity to be reckoned with in the future of. I'm usually wary when I have to review an artist's sophomore album. With 20/20, Trip Lee offers up a wide array of subject matter as he hits on. Trip Lee - 20/20 - Music. Editorial Reviews the critically-acclaimed debut, If They Only Knew, Trip Lee wants to give every listener 20/20 vision. Find album reviews, stream songs, credits and award information for 20/20 - Trip Lee on AllMusic - - Trip Lee is a fresh new voice in the growing. Many thanks to Ben Washer of Reach Records for this review copy! Before I begin my review of Trip Lee's 20/20, some prefatory remarks are in. Okay lets start with the track listing: 1. 20/20 Intro 2. Superstar (Eyes Off Me) 3. Real Vision 4. Inexhaustible 5. Who Is Like Him? 6. We Told Em. 20/20, an Album by Trip Lee. Released May 20, on Reach (catalog no. BNZAI; CD). Genres: Christian Hip Hop. 20/20 by Trip Lee,Album Information And Artist Biographies At NewReleaseToday. Christian Music Coming To You New, Every Week. 20/20 is the second studio album from Christian rap artist Trip Lee. The album was released in , through Reach Records. The album debuted at No. on the Billboard Reception[edit]. The album received generally positive reviews; Trailblaza of Rapzilla had. The Good Life is the fourth studio album from Christian rap artist Trip Lee. -

SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists 1218 Songs, 3.2 Days, 7.69 GB

Page 1 of 35 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists 1218 songs, 3.2 days, 7.69 GB Name Time Album Artist 1 Insomniac Dreaming (prod by Bla… 3:33 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists A.Dd+ 2 In Silence 3:57 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Abandoned Pools 3 Streets 3:53 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Abby 4 Soul Food 2:10 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Above All 5 Marguerite 2:58 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists The Abramson Singers 6 Whisky Eyes 3:31 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Acollective 7 Holy Ghosts 2:22 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists The Act Rights 8 Prophecy 4:37 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Adam & The Amethysts 9 Saturday 4:24 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Adam Faucett 10 616 4:00 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Adam WarRock 11 I'm Alright 3:41 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Agent Ribbons 12 Molom 4:03 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Agnes Mercedes 13 Dançando 5:50 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Agridoce 14 String Quartet in F Major—Vif et… 5:54 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Aiana String Quartet 15 Shine 3:44 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Ain't No Love 16 New Blood 4:02 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists The Airplane Boys 17 Racist 2:35 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists aKa Frank 18 Say Yes 3:25 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Akina Adderley & The Vintage Pl… 19 Hold On 3:48 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Alabama Shakes 20 Money for the Weekend 3:44 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Alberta Cross 21 Bare Nang Poppers 2:20 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Aleister X 22 Cómo puedes vivir contigo mismo? 4:21 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Alex Anwandter 23 Are You 3:40 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Alex Cuba 24 Seeds 3:45 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Alexander & The Grapes 25 Facemelter 4:01 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Alexander Spit 26 Catamaran 3:30 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists Allah-Las 27 City Boy 2:47 SXSW 2012 Showcasing Artists AM & Shawn Lee 28 A.M.B.I.T.I.O.N. -

Blood Bought Radio Worldwide Report Dates from 2/28/2021 - 3/6/2021

BROADCASTER RAW DATA DRT SUMMARY REPORT BLOOD BOUGHT RADIO WORLDWIDE REPORT DATES FROM 2/28/2021 - 3/6/2021 ARTIST SONG TITLE LABEL TOTAL SPINS TUNE INTO WORD OF KNOWEDGE RADIO SHOW BRIDGING THE GAP EVERY SUNDAY AT 6PM EST ON BLOOD BOUGHT MOVEMEMENT LLC RADIO UNKNOWN 23 KNA-LEDGE X PASTOR TIM MOSES - WORD OF KNOWLEDGE RADIO SHOW WITH JUST DANIELLE (2021 S9 EP7) UNKNOWN 22 BRIDGING THE GAP CONNECT WITH WORD OF KNOWLEDGE RADIO MOVEMENT LLC SHOW @WOKRADIOSHOW UNKNOWN 16 WORD OF KNOWLEDGE RADIO SHOW NEW YEAR NEW SEASON AND NEW STATIONS UNKNOWN 16 MOSES DANIELS BEYOND COMPREHENSION UNKNOWN 15 DJ KOJACK BREAK BREAD MIX SHOW WITH DJ KOJACK (MIX 34) UNKNOWN 14 SEVIN SURRENDER UNKNOWN 14 D ROAD BBR HIS HOP RADIO SHOW PROMO UNKNOWN 13 DJ KOJACK BREAK BREAD MIX SHOW WITH DJ KOJACK (MIX 35) UNKNOWN 13 BOY WONDA GUTTA 2 GLORY (FEAT TIM MOSES) UNKNOWN 12 BOY WONDA X CHOZEN SHUT IT DOWN UNKNOWN 12 BRIDGING THE GAP VISIT TODAY AT MOVEMENT LLC WWWBRIDGINGTHGAPMOVEMENTLLCCOM UNKNOWN 12 DJ KOJACK BREAK BREAD MIX SHOW WITH DJ KOJACK (MIX 32) UNKNOWN 12 DJ KOJACK BREAK BREAD MIX SHOW WITH DJ KOJACK (MIX 33) UNKNOWN 12 DJ KOJACK BREAK BREAD MIX SHOW WITH DJ KOJACK (MIX 36) UNKNOWN 12 ELISEO WAY - ANTI SOCIAL UNKNOWN 12 HIS HOP NATION AUDRA COTTON UNKNOWN 12 ILLUMINATE ERACISM (FT SEVIN FAITH PETTIS & ESRAELIA) UNKNOWN 12 INTERNATIONAL SHOW RISE (FEAT THE EAGLE ROCK GOSPEL SINGERS) UNKNOWN 12 MR BRIDGE WHY ARENT YOU ABLE UNKNOWN 12 PASTOR TIM MOSES/LIFESUPPORT/JENESIS JEREMIAH UNKNOWN 12 REALITY BOOKING & PROMOTIONS CHH & CHRISTIAN DJS ONLY!! FREE -

Everything Subject to Change. SXSW Showcasing Artists Current As of March 8, 2017

424 (San José COSTA RICA) Lydia Ainsworth (Toronto ON) ANoyd (Bloomfield CT) !!! (Chk Chk Chk) (Brooklyn NY) Airways (Peterborough UK-ENGLAND) AOE (Los Angeles CA) [istandard] Producer Experience (Brooklyn NY) Aj Dávila (San Juan PR) Apache (VEN) (Cara VENEZUELA) #HOODFAME GO YAYO (Fort Worth TX) Jeff Akoh (Abuja NIGERIA) Apache (San Francisco CA) 070 Shake (North Bergen NJ) Federico Albanese (Berlin GERMANY) Ape Drums (Houston TX) 14KT (Ypsilanti MI) Latasha Alcindor (Brooklyn NY) Ben Aqua (Austin TX) 24HRS (Atlanta GA) AlcolirykoZ (Medellín COLOMBIA) Aquilo (London UK-ENGLAND) 2 Chainz (Atlanta GA) Alexandre (Austin TX) Sudan Archives (Los Angeles CA) 3rdCoastMOB (San Antonio TX) Alex Napping (Austin TX) Arco (Granada SPAIN) The 4onthefloor (Minneapolis MN) ALI AKA MIND (Bogotá COLOMBIA) Ariana and the Rose (New York NY) 4x4 (Bogotá COLOMBIA) Alikiba (Dar Es Salaam TANZANIA) Arise Roots (Los Angeles CA) 5FINGERPOSSE (Philadelphia PA) All in the Golden Afternoon (Austin TX) Arkansas Dave (Austin TX) 5ive (Earth TX) Allison Crutchfield and the Fizz (Philadelphia Brad Armstrong (Rhinebeck NY) PA) 808INK (London UK-ENGLAND) Ash Koosha (Iran / London UK-ENGLAND) All Our Exes Live In Texas (Newtown NSW) 9th Wonder (Winston-Salem NC) Ask Carol (Oslo NORWAY) Al Lover (San Francisco CA) A-Town GetDown (Austin TX) Astro 8000 (Philadelphia PA) Annabel Allum (Guildford UK-ENGLAND) A$AP FERG (Harlem NY) A Thousand Horses (Nashville TN) August Alsina (New Orleans LA) A$AP Twelvyy (New York NY) Nicole Atkins (Nashville TN) Altre di B (Bologna ITALY) -

Lecrae Rebel Album Zip Download Lecrae Restoration (ALBUM) Months Ago Lecrae Promised to Released His 2020 Album “RESTORATION” After Many Fans Expectation

lecrae rebel album zip download Lecrae Restoration (ALBUM) Months ago Lecrae promised to released his 2020 album “RESTORATION” after many fans expectation.. Today you need not to wait any longer as the talented gospel singer LECRAE MOORE just drops the new 2020 album tagged RESTORATION. lecrae restoration mp3 download (lecrae restoration zip) ABOUT LECRAE Born on October 9, 1979 in Houston, Texas, Lecrae Moore was raised by a poor single mother who exposed him to drugs. Moving to several places throughout his upbringing, he was able to witness various cultures and backgrounds, sad to say he idolized and adapted the street life. By 16 years old he was drinking, doing drugs, stealing and fighting, but was soon transformed into a newborn Christian upon attending a Christian conference led by James White. He led a totally different life since then, a Christ-centered life. He began writing lyrics about his ups and downs and at 25, he signed to Reach Records and immediately released his debut album entitled “Real Talk”. Witnessing firsthand how the set had positively impacted people in showbiz and broader, he began working on a follow-up. Titled “After the Music Stops” (2006), the sophomore record was commercially success and surpassed his debut album by reaching no. 5 on the Billboard Gospel Album charts. It was also nominated for the Dove Awards and spawned hit single “Jesus Muzik”. Two years later, Lecrae occupied Billboard charts and iTunes with his third album “Rebel” which remained on the Gospel charts for 78 weeks straight. It thus became the first Christian hip- hop album to reach No. -

Tedashii's Biography “I Wanted to Do College Ministry…Being a Part of Christian Hip Hop Was Never the Plan,” He Reveals

Tedashii's Biography “ I wanted to do college ministry…being a part of Christian Hip Hop was never the plan, ” he reveals. While Tedashii’s robust stature and delivery on the mic catch the attention of most, his gentle spirit hints at an even deeper story behind the man and the music. Born in East Texas, Tedashii “ TDot ” Anderson was raised to be very family-oriented, respectful and appreciative, but embracing the latter was often difficult in light of the economic conditions his family faced. Television became an escape for him as he admits to wanting a different life, “I really wanted to get away, ” Tedashii recalls. He envied the Huxtable lifestyle and eloquence and desired the urbanized southern version, topped off with a candy-painted car on 26's. His ambitions would soon mirror those he stayed up watching on television and read about in books. In high school, he joined the band to play jazz, studied black history, reveled in poetry, endeavored to become a renaissance man, and even idolized Ted Kopple. Tedashii remembers being different than his peers in his vast interests, but as expected for a Texas boy, Samoan at that, he also played football. By most standards, he was a well- rounded, good person--most, but not all. Tedashii was given a wake-up call in college after being confronted by a student who overheard him using profanity. “ He told me that I was a sinner and basically shared the Gospel with me that day.” Some time later, after going to a Christian event on campus and seeing hundreds of urban students authentically worship God, he received Jesus and found new life in Christ instead of Hollywood. -

Program Overview Program Overview

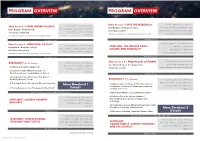

PROGRAM OVERVIEW PROGRAM OVERVIEW Main Session 3 | INTO THE WILDERNESS Saturday 22 May unless stated otherwise Main Session 1 | FROM HEAVEN TO EARTH Saturday 22 May unless stated otherwise Kuki Rokhum | Katharine Hayhoe UTC: 1:30pm | PDT 06:30am | EDT 9:30am | BST René August | Krish Kandiah UTC: 6am | PDT 11pm 21 May | EDT 2am BST 7am | Hosted by: London 2:30pm | SAST/CEST 3:30pm | HKT 9:30pm | AEST Hosted by: Hong Kong SAST/CEST 8am | HKT 2pm | AEST 4pm Simultaneous Cantonese translation through Zoom audio 11:30pm | NZST 01:30am Sunday 23 May Simultaneous Cantonese translation through Zoom audio NZST 6pm 30 minute break 30 minute break Main Session 2 | FROM ISRAEL TO EGYPT Saturday 22 May: UTC: 3:30pm | PDT 08:30am Saturday 22 May unless stated otherwise Roy Njuabe | Branches of Hope SPOTLIGHT: THE UNJUST CRISIS: EDT 11:30am | BST 4:30pm UTC: 8am | PDT 1am | EDT 4am | BST 9am | SAST/ CLIMATE AND INEQUALITY Hosted by: Hong Kong SAST/CEST 5:30pm | HKT 11:30pm CEST 10am | HKT 4pm | AEST 6pm | NZST 8pm Sunday 23 May: AEST 1:30am | NZST 3:30am Simultaneous Cantonese translation through Zoom audio 30 minute break 50 minute break Main Session 4 | FROM PLACES OF POWER Saturday 22 May: UTC: 5pm | PDT 10am BREAKOUT 1 (40-60minutes) Saturday 22 May unless stated otherwise Lisa Sharon Harper | Rev Eugene Cho EDT 1pm | BST 6pm | SAST/CEST 7pm UTC: 10am | PDT 3am | EDT 6am | BST 11am ⊲ Church and public engagement Sunday 23 May: HKT 1am | AEST 3am | NZST 5am AST/CEST 12noon | HKT 6pm | AEST 8pm Hosted by: London ⊲ Inspired to Fight: What Individuals -

John Piper (Endorsed by David Slayton) and “Holy Hip-Hop”

John Piper (endorsed by David Slayton) and “Holy Hip-Hop” John Piper’s role in legitimizing and promoting hip-hop culture in the Church is an important aspect of his ministry that is sometimes overlooked. To really understand John Piper’s ministry we must examine his association with holy hip hop culture that is sweeping through the young, restless and reformed New Calvinist movement. The purpose of this article is to provide information on Piper’s involvement and support for holy hip-hop. In October 2006, John Piper invited rap artist Curtis, ‘the Voice’, Allen to perform in Bethlehem Baptist Church. The significance of this event is that it legitimized the so-called holy hip-hop movement among New Calvinists. The fact that a leading theologian of New Calvinism had publicly given his blessing to rap music in the Church was a symbolic event that opened the floodgates. If Piper was in favor of rap artists performing in the Church, who could be against it? In January 2008, Desiring God published a series of three videos that endorsed the ministry of rap artist Lecrae. In the videos Lecrae talks about his life growing up in the inner city, his conversion to Christ, and his unconventional ministry. http://youtu.be/c5L4on0AHik Desiring God and Reach Life Ministries in partnership The close relationship between John Piper and rap artist Lecrae is illustrated by the fact that their respective organizations, Desiring God Ministries and Reach Records, Rap artist Lecrae have been collaborating for a number of years. Associated with Reach Records is a group of rap artists known as ‘116 Clique’ (pronounced one-one-six click).