Télécharger La Page En Format

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Dec 2004 Current List

Fighter Opponent Result / RoundsUnless specifiedDate fights / Time are not ESPN NetworkClassic, Superbouts. Comments Ali Al "Blue" Lewis TKO 11 Superbouts Ali fights his old sparring partner Ali Alfredo Evangelista W 15 Post-fight footage - Ali not in great shape Ali Archie Moore TKO 4 10 min Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 ABC Commentary by Cossell - Some break up in picture Ali Bob Foster KO 8 21-Nov-1972 British CC Ali gets cut Ali Brian London TKO 3 B&W Ali in his prime Ali Buster Mathis W 12 Commentary by Cossell - post-fight footage Ali Chuck Wepner KO 15 Classic Sports Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 B&W Commentary by Don Dunphy - Ali in his prime Ali Cleveland Williams TKO 3 14-Nov-1966 Classic Sports Ali in his prime Ali Doug Jones W 10 Jones knows how to fight - a tough test for Cassius Ali Earnie Shavers W 15 Brutal battle - Shavers rocks Ali with right hand bombs Ali Ernie Terrell W 15 Feb, 1967 Classic Sports Commentary by Cossell Ali Floyd Patterson i TKO 12 22-Nov-1965 B&W Ali tortures Floyd Ali Floyd Patterson ii TKO 7 Superbouts Commentary by Cossell Ali George Chuvalo i W 15 Classic Sports Ali has his hands full with legendary tough Canadian Ali George Chuvalo ii W 12 Superbouts In shape Ali battles in shape Chuvalo Ali George Foreman KO 8 Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Gorilla Monsoon Wrestling Ali having fun Ali Henry Cooper i TKO 5 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only Ali Henry Cooper ii TKO 6 Classic Sports Hi-Lites Only - extensive pre-fight Ali Ingemar Johansson Sparring 5 min B&W Silent audio - Sparring footage Ali Jean Pierre Coopman KO 5 Rumor has it happy Pierre drank before the bout Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 Superbouts Ali at his relaxed best Ali Jerry Quarry i TKO 3 Ali cuts up Quarry Ali Jerry Quarry ii TKO 7 British CC Pre- & post-fight footage Ali Jimmy Ellis TKO 12 Ali beats his old friend and sparring partner Ali Jimmy Young W 15 Ali is out of shape and gets a surprise from Young Ali Joe Bugner i W 12 Incomplete - Missing Rds. -

Boxing Edition

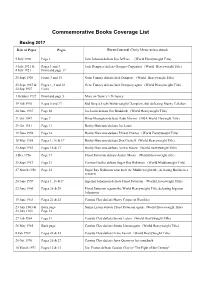

Commemorative Books Coverage List Boxing 2017 Date of Paper Pages Event Covered (Daily Mirror unless stated) 5 July 1910 Page 3 Jack Johnson defeats Jim Jeffries (World Heavyweight Title) 3 July 1921 & Pages 1 and 3 Jack Dempsey defeats Georges Carpentier (World Heavyweight Title) 4 July 1921 Front and page 17 25 Sept 1926 Front, 3 and 15 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1927 & Pages 1, 3 and 18 Gene Tunney defeats Jack Dempsey again (World Heavyweight Title) 24 Sep 1927 Front 1 October 1927 Front and page 5 More on Tunney v Dempsey 19 Feb 1930 Pages 5 and 22 Kid Berg is Light Welterweight Champion after defeating Mushy Callahan 24 June 1937 Page 30 Joe Louis defeats Jim Braddock (World Heavyweight Title) 21 Oct 1947 Page 7 Rinty Monaghan defeats Dado Marino (NBA World Flyweight Title) 29 Oct 1951 Page 11 Rocky Marciano defeats Joe Louis 19 June 1954 Page 14 Rocky Marciano defeats Ezzard Charles (World Heavyweight Title) 18 May 1955 Pages 1, 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Don Cockell (World Heavyweight Title) 23 Sept 1955 Pages 16 & 17 Rocky Marciano defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight Title) 3 Dec 1956 Page 17 Floyd Patterson defeats Archie Moore (World Heavyweight title) 25 Sept 1957 Page 23 Carmen Basilio defeats Sugar Ray Robinson (World Middleweight Title) 27 March 1958 Page 23 Sugar Ray Robinson wins back the Middleweight title, defeating Basilio in a rematch 28 June 1959 Pages 1, 16 &17 Ingemar Johansson defeats Floyd Patterson (World Heavyweight Title) 22 June 1960 Pages 28 & 29 Floyd Patterson -

The Power to Win!

THURSDAY NOVEMBER 17, 2016 DAYLAS VEGAS CONVENTION 2 CENTER THE OFFICIAL SHOW NEWS HOW DAILY NORTH AMERICA’S LARGEST METALS FORMING, FABRICATING, WELDING AND FINISHING EVENT TODAY The Power to Win! Leonard Scores Another Knockout with Keynote Speech at FABTECH 2016 WELDERS WITHOUT BORDERS: WELDING THUNDER TEAM When the crowd rose to its feet at the The Principles of Success FABRICATION COMPETITION end of his keynote presentation yester- 7:00 AM - 1:00 PM day morning, Sugar Ray Leonard must "Boxing has given me an incredible ride," Silver Parking Lot have had a sense of déjá vu. For Leonard, said Leonard. "It's afforded me the oppor- tunity to escape poverty, to travel the world WOMEN OF FABTECH BREAKFAST getting people up and out of their seats WITH TECH TOUR in Las Vegas is something he’s done for and meet important people like Nelson 7:30 - 10:30 AM decades, first as a world-championship Mandela; but it's also taught me that the Room N101 boxer, later as an author, entrepreneur, same principles that I applied to become Must be registered to attend. and motivational speaker, and always with world champion are applicable in the suc- the confidence and charisma that marked cess of life and business.” DEVELOPMENT TRENDS IN him early on as an American hero. ADDITIVE MANUFACTURING Among the principles Leonard touched on AND 3D PRINTING When Leonard was introduced to the in his speech: 8:30 - 9:30 AM gathering at the FABTECH Theater, he • Preparation (i.e., roadwork) FABTECH Theater bounded to the stage flashing a conta- • Overcoming failure losses, and one draw; many of his victories Central Hall Lobby gious smile, much as he used to do when (e.g., over Tommy “The Hit Man” Hearns, • Determination stepping between the ropes to defend a BLUES, BREWS AND BBQ “Marvelous” Marvin Hagler, and Roberto • Focus title. -

Tour De France, 1986

SLAYING THE BADGER GREG LEMOND, BERNARD HINAULT AND THE GREATEST TOUR DE FRANCE RICHARD MOORE Copyright © 2012 by Richard Moore All rights reserved. Printed in the United States of America. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic or photocopy or otherwise, without the prior written permission of the publisher except in the case of brief quotations within critical articles and reviews. 3002 Sterling Circle, Suite 100 Boulder, Colorado 80301-2338 USA (303) 440-0601 · Fax (303) 444-6788 · E-mail [email protected] Distributed in the United States and Canada by Ingram Publisher Services Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Moore, Richard. Slaying the badger: Greg Lemond, Bernard Hinault, and the greatest Tour de France / Richard Moore. p. cm. ISBN 978-1-934030-87-5 (pbk.) 1. Tour de France (Bicycle race) (1986) 2. LeMond, Greg. 3. Hinault, Bernard, 1954– 4. Cyclists—France—Biography. 5. Cyclists—United States—Biography. 6. Sports rivalries. I. Title.= GV1049.2.T68M66 2012 796.620944—dc23 2012000701 For information on purchasing VeloPress books, please call (800) 811-4210 ext. 2138 or visit www.velopress.com. Cover design by Landers Miller Design, LLC Interior design and composition by Anita Koury Cover photograph by AP Photo/Lionel Cironneau Interior photographs by Offside Sports Photography except first insert, page 2 (top): Corbis Images UK; page 5 (top): Shelley Verses; second insert, page 2 (bottom): Graham Watson; page 8 (top right): Pascal Pavani/AFP/Getty Images; page 8 (bottom): James Startt Text set in Minion. -

Autopac Renewal

4, Thursday, January 26, 1984 Page 12 Friday, February 10, 1984 RED RIVER COMMUNITY COLLEGE If all the INFORMATION IS CORRECT Autopac Renewal and you DO NOT WISH to change the coverage, — READ the Declarations (back) • and SIGN and date the form (back) SELECT full or time payments (front) RED RIVER COMMUNITY COLLEGE ISSUE a cheque or money order payable to STUDENTS' ASSOCIATION the 'MINISTER OF FINANCE' for the amount selected, FULLor TIME PAYMENT. — ENCLOSE your payment with the renewal form in an envelope. DROP the application off at our office, Room DM20. PICK UP the validated renewal Your Students' Association E.vecutive has arranged 24 hours later. station for your AUTOPAC renewal. What's Inside: "DROP-Oar F " ' and "PICK-UP '' It is hoped that you will .find this service a convenience. If the INFORMATION IS INCORRECT or you wish to change the coverage, WE CANNOT be of service to you. Visit the agent of your choice. If you've been confused about where you can Instructions and can't smoke in the college, it seems you may not have to worry at all. See details of the new that all the information printed on the tjont of Take a load off your mind, avoid late hasSels, smoking by-law on page 2. ENSURE the renewal application is correct. It reflects give us a post-dated cheque with your insurance Now! the coverage you had last year. Then just pick up your renewal at the end of February. whether the coverage you had is adequate OUR OFFICE WILL BE OPEN CONSIDER for your needs. -

Some Say That There Are Actually Four Players from Outside the U.K

Some say that there are actually four players from outside the U.K. that have been World Champion citing Australian Horace Lindrum, a nephew of Walter, who won the title in 1952. This event was boycotted by all the British professional players that year and for this reason many in the sport will not credit him with the achievement. The other three to make the list are first, Cliff Thorburn from Canada in 1980, defeating Alex Higgins 18 frames to 16. He also made the first 147 maximum break of the World Championships in his 1983 second round match against Terry Griffiths which he won 13 – 12. Third was Neil Robertson who won a never to be forgotten final against Scot Graeme Dott 18 frames to 13 in 2010. His route to the final had started with a match against Fergal O’Brien which he won 10 – 5. Next up was a heart stopping, come from behind win over Martin Gould after trailing 0 – 6 and again 5 – 11 before getting over the line 13 – 12. Steve Davis, multiple World Champion, was next and dispatched 13 – 5 which brought him to the semi finals and a 17 – 12 victory over Ali (The Captain) Carter. Third here but really second on the list is Ken Doherty from Eire who won the World title by beating Stephen Hendry, multiple World Champion winner from Scotland, at the Crucible in 1997 winning 18 - 12. Ken had previously become the I.B.S.F. amateur World Champion in 1989 by defeating Jon Birch of England 11 frames to 2 in the final held in Singapore. -

Exiting Toward Excellence

Monday, November 3, 1986 RED RIVER COMMUNITY COLLEGE Monday, November 17, 1986 Page 20 M 43/41/4, Staff development da NOV 1 8 1986 PERIODICALS draws capacity crowd Learning Resources Centre 1 1 Dr. Arnold aimark addresses the problem of South Gym leaves standing room only. juggling increased educational services in an era of budget restraint. by Annette Martin staff/administration popula- said, made off with sand- tion at the college, says wiches meant for attendees. Red River Community Col- McLaren. Noteably, the Students' lege's first staff development Rick Dedi, assistant to the Association office was also day on Nov. 13 was coined a president, said he received closed for the day. success. equally enthusiastic responses Joan McLaren, director of This development program from participants. Although program and staff develop- was different from past ones co-ordinator Roy Pollock ment, said she received for two reasons. First, it was could not be reached for com- nothing but positive feedback an all-day in-service, and ment, Dedi said the event has and predicts this will become a secondly, it involved more surpassed even Pollock's most bi-annual event. than just instructors but optimistic predictions. The purpose of Thursday's administrators, secretaries, There were 57 workshops in-service was to ferment new 1 clerks and cooks, as well. with attendance at each rang- skills and ideas and instruct S.A. Business Director Don ing from ten to 90, said people about new programs Hillman was critical of the in- McLaren. and career advancement service. It involved so many The only flop was the lunch opportunities. -

Tony Knowles

Tony Knowles - Fondly known as Knowlesy By Elliott West Tony Knowles is one of the iconic players of the golden years of snooker Name: Tony Knowles and played all the game’s greats in the 1980s. This quietly spoken, gentle Born: 13 June 1955 giant with an infectious grin first started playing snooker at the age of nine Nationality: England and was always destined for the heady heights of the sport. I have lucky Highest Break: 139 enough to meet Tony and shared some time with him during an exhibition match in Kent with my good friend Joe Johnson. A raconteur of the old days,” Knowlesy“ as we like to call him, is a master of the game, knowing every shot and angle there is on a snooker table and his trick shots are unbelievable. Knowles first made his name in snooker when as a qualifier he defeated the iconic Steve Davis in the first round of the World Championship in 1982. Davis was on a momentous winning streak at the time, having convincingly won the 1981 World Championship. However the lad from Bolton was not phased by this Romford kid and produced some of his best snooker in the match, ending it with a 10-1 drubbing over Davis. This match left Steve reeling and is equal in defeats to the 1985 World Championship black ball win by Dennis Taylor. Like so many in the sport, it is frustrating that Tony didn’t win big in snooker and all the top titles eluded him for his playing career. However there was silverware on the way on his illustrious career path. -

BAM Media Release Fall 2015

` MEDIA RELEASE The Broadcasters Association of Manitoba Announces Fall 2015 Award Winners, New Board Broadcast Excellence Award and BAM Hall of Fame Award Winnipeg, MB – The Broadcasters Association Of Manitoba honoured two outstanding individuals during their Annual Fall Conference. The event was held Thursday September 24th. BAM President Cam Clark noted “these awards allow us to recognize those who have made significant contributions to our industry. The two recipients receiving awards this fall - have made a lasting impact on the broadcast industry through their management and on-air communications to the community and corporately.” HALL OF FAME - BROADCASTER AWARD JOE PASCUCCI Joe Pascucci was honored with the BAM Hall of Fame Broadcaster Award. This award recognizes lifetime achievement for those individuals who have created a legacy in our industry. Joe was a regular fixture in households across Manitoba for more than 32 years and through all of them, demonstrated an incredible commitment and compassion to Manitoba’s sports scene. When Pascucci was hired by Global TV in 1982 the Toronto born sports broadcaster never imagined he would remain in Winnipeg for another three decades. But as Pascucci said on the eve of his retirement in 2014, he couldn’t help himself. “I was doing so much, every day was exciting. The people were fantastic. I loved it.” There isn’t a sport Joe hasn’t covered. With a calming read and incredible insight he provided analysis of the Winnipeg Blue Bombers, Winnipeg Jets (hosting Winnipeg Jets hockey on Global) junior hockey, Provincial Championship curling, boxing, and many amateur sports. In 1991 Joe helped create Sportsline, a popular 11 pm show that ran for more than a decade and launched the careers of many broadcasters who are still on TSN and Sportsnet. -

Crucible's Greatest Crucible's Greatest

THETHE CRUCIBLE’SCRUCIBLE’S GREATESTGREATEST MATCHESMATCHES FortyForty YearsYears ofof Snooker’sSnooker’s WorldWorld ChampionshipChampionship inin SheffieldSheffield HECTOR NUNNS Foreword by Barry Hearn Contents Foreword . 7 Preamble . 10 . 1 The. World Championship finds a spiritual home . 21 . 2 Cliff. Thorburn v Alex Higgins, 1980, the final . 30 3 Steve. Davis v Tony Knowles, 1982, first round . 39. 4 Alex. Higgins v Jimmy White, 1982, semi-final . 48 5 Terry. Griffiths v Cliff Thorburn, 1983, last 16 . 57 6. Steve Davis v Dennis Taylor, 1985, final . 67 . 7 Joe. Johnson v Steve Davis, 1986, final . 79. 8. Stephen Hendry v Jimmy White, 1992, final . 89 . 9. Stephen Hendry v Jimmy White, 1994, final . 97 . 10 . Stephen Hendry v Ronnie O’Sullivan, semi- final, 1999 . .109 11 . Peter Ebdon v Stephen Hendry, 2002, final . 118 12 . Paul Hunter v Ken Doherty, 2003, semi- final . 127 13 . Ronnie O’Sullivan v Stephen Hendry, 2004, semi-final . .138 14 . Ronnie O’Sullivan v Peter Ebdon, 2005, quarter-final . .148 . 15 . Matthew Stevens v Shaun Murphy, 2007, quarter-final . .157 16. Steve Davis v John Higgins, 2010, last 16 . 167. 17 . Neil Robertson v Martin Gould, 2010, last 16 . .179 . 18. Ding Junhui v Judd Trump, 2011, semi-final . .189 . 19. John Higgins v Judd Trump, 2011, final . 199 20 . Neil Robertson v Ronnie O’Sullivan, 2012, quarter-final 208 Bibliography and research . 219 . Select Index . 221 Preamble by Hector Nunns CAN still recall very clearly my own first visit to the Crucible Theatre to watch the World Championship live – even though I the experience was thrillingly brief. -

Remembering the Tour De Trump Cheering for a Mexican to Beat a Russian — Memories Memories

PHOTO: Graham Watson — remembering the tour de trump Cheering for a mexiCan to beat a russian — memories memories In 2016 a strange rich man wants to become the leader of his nation and have Mexico pay for a “great, great wall” on his country’s southern border. Years ago, when the same man financed a race, a Mexican claimed the title… There were only two Tours de Trump and the second audience who wondered why their golf game or fishing edition left a deep impression on me, the video cassette show was suddenly replaced by images of guys in lycra. But of the stage race was watched over and over until, at just to see the 7-Eleven team racing against Panasonic and some point, the tape broke. I grew up in Denver and PDM on American soil was thrilling. We marvelled at how by 14 was already racing with the top amateurs and the Europeans refused to wear helmets, especially Gert-Jan some professionals. The pros used the Colorado races as a Theunisse who was determined to let his long hair flow strenuous warm-up for the bigger, international stage races. behind him as he charged up the Catskills. We had these weekday rides at Meridian Park just south of By the second Tour de Trump, in 1990, LeMond had just Denver where my friends and I would jump in the race and signed a $5.5 million contract, 7-Eleven was fading, the guys like Davis Phinney, Andy Hampsten, and Olympic smaller domestic teams like Coors Light, Crest and Taco gold medal-winner Alexi Grewal would chew us up and Bell were rising. -

Respondents 25 Sca 001378

Questions about a Champion "If a misdeed arises in the search for truth, it is better to exhume it rather than conceal the truth." Saint Jerome. "When I wake up in the morning, I can look in the mirror and say: yes, I'm clean. It's up to you to prove that I am guilty." Lance Armstrong, Liberation, July 24,2001. "To deal with it, the teams must be clear on ethics. Someone crosses the line? He doesn't have the right to a second chance!" Lance Armstrong, L'Equipe, April 28, 2004. Between the World Road Champion encountered in a Norwegian night club, who sipped a beer, talked candidly, laughed easily and never let the conversation falter, and the cyclist with a stem, closed face, who fended off the July crowd, protected by a bodyguard or behind the smoked glass of the team bus, ten years had passed. July 1993. In the garden of an old-fashioned hotel near Grenoble, I interviewed Armstrong for three hours. It was the first professional season for this easygoing, slightly cowboyish, and very ambitious Texan. I left with a twenty-five-page interview, the chapter of a future book11 was writing about the Tour de France. I also took with me a real admiration for this young man, whom I thought had a promising future in cycling. Eight years later, in the spring of 2001, another interview. But the Tour of 1998 had changed things. Scandals and revelations were running rampant in cycling. Would my admiration stand the test? In August 1993, it was a happy, carefree, eloquent Armstrong, whom Pierre Ballester, met the evening after he won the World Championship in Oslo.