CHAPTER6 Stereotyping, Prejudice, and Discrimination

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Framing “The Gypsy Problem”: Populist Electoral Use of Romaphobia in Italy (2014–2019)

social sciences $€ £ ¥ Article Framing “The Gypsy Problem”: Populist Electoral Use of Romaphobia in Italy (2014–2019) Laura Cervi * and Santiago Tejedor Department of Journalism and Communication Sciences, Autonomous University of Barcelona, Campus de la UAB, Plaça Cívica, 08193 Bellaterra, Barcelona, Spain; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Received: 12 May 2020; Accepted: 12 June 2020; Published: 17 June 2020 Abstract: Xenophobic arguments have long been at the center of the political discourse of the Lega party in Italy, nonetheless Matteo Salvini, the new leader, capitalizing on diffused Romaphobia, placed Roma people at the center of his political discourse, institutionalizing the “Camp visit” as an electoral event. Through the analysis of eight consecutive electoral campaigns, in a six year period, mixing computer-based quantitative and qualitative content analysis and framing analysis, this study aims to display how Roma communities are portrayed in Matteo Salvini’s discourse. The study describes how “Gypsies” are framed as a threat to society and how the proposed solution—a bulldozer to raze all of the camps to the ground—is presented as the only option. The paper concludes that representing Roma as an “enemy” that “lives among us”, proves to be the ideal tool to strengthen the “us versus them” tension, characteristic of populist discourse. Keywords: populism; Romaphobia; far right parties; political discourse 1. Introduction Defining Roma is challenging. A variety of understandings and definitions, and multiple societal and political representations, exist about “who the Roma are” (Magazzini and Piemontese 2019). The Council of Europe, in an effort to harmonize the terminology used in its political documents, apply “Roma”—first chosen at the inaugural World Romani Congress held in London in 1971—as an umbrella term that includes “Roma, Sinti, Travellers, Ashkali, Manush, Jenische, Kaldaresh and Kalé” and covers the wide diversity of the groups concerned, “including persons who identify themselves as Gypsies” (2012). -

WORLD on the MOVE the MOVE on WORLD Recent Publications in Migration NEWSLETTER for the AMERICAN SOCIOLOGICAL ASSOCIATION’S

Volume 11, No. 2 Mexican-American Mobility: Incorporation or 4th Generation Decline? By Susan K. Brown Questions about the numbers and characteristics of immigrants and their impact in the United States have constituted the fodder of public policy debates for more than 40 years. A particularly hot-button issue has involved perceptions of how successfully Mexican immigrants are being incorporated, for several reasons beyond the sheer size of the group. First, many enter without authorization and thus attract negative attention. Second, many are such recent arrivals that judgments about their experi- ence often rely on just a few years’ data and thus underestimate how the groups will eventually fare. Third, pessimistic commentaries by prominent scholars like Huntington (2004) claim that Mexican-origin persons have neither the desire nor ability to be- come incorporated in the United States. This note reports some preliminary results from my research relevant to the debate on the incorporation of those of Mexican origin. The data come from the recently finished survey on Intergenerational Immigrant Mobility in Metropolitan Los Angeles (IIMMLA). While the survey reached the young adult children of immigrants of many nationalities, it substantially oversampled those of Mexican origin by including respondents from this group who came not only from the 1.5 or second generations, but also from the immigrant, third, and fourth or higher generations. On a variety of indicators, the data show steady upward mobil- ity from the first through the third generations. Then the cross- generation pattern deviates from what straight-line assimilation would expect. The fourth or later generation group does not appear to be faring as well as the third. -

Racial Attitudes and White Upbringing Master Thesis

1 UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK IN PRAGUE Department of Psychology Racial Attitudes and White Upbringing Master Thesis Prague 2018 B.A. Psychology Svobodova 1 1 UNIVERSITY OF NEW YORK IN PRAGUE Department of Psychology Racial Attitudes and White Upbringing Master Thesis Supervisor : Submitted by: Jan Zahorik Sarah Svobodova Prague, 2018 1 Declaration I hereby declare that I wrote this thesis individually based on literature and resources stated in references section. In Prague: 15.8.2018 Signature 1 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would first like to thank my thesis advisor Dr. Jan Zahorik of the at The University of New York. He consistently allowed this paper to be my own work, but steered me in the right the direction whenever he thought I needed it. I would also like to acknowledge Dr. Radek Ptacek, Director of the Masters of Psychology program for all of his continued support during this thesis. Finally, I must express my gratitude to my parents, my sister, my friends and to my partner for providing me with their continued support throughout my years of study and through the process of researching and writing this thesis. This accomplishment would not have been possible without them. Thank you. 1 Table of Contents ABSTRACT...................................................................................................................7 INTRODUCTION.........................................................................................................8 LITERATURE REVIEW................................................................................................9 -

Ambivalent Prejudice Toward Immigrants: the Role of Social Contact and Ethnic Origin

Ambivalent Prejudice toward Immigrants: The Role of Social Contact and Ethnic Origin Hisako Matsuo, Kevin McIntyre, Ajlina Karamehic-Muratovic, Wai Hsien Cheah, Lisa Willoughby, & John Clements 1 Emma Lazarus’ famous poem engraved at the base of the Statue of Liberty. Give me your tired, your poor, Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free, The wretched refuse of your teeming shore --Emma Lazarus, “The New Colossus” 2 Immigrants to the US in the past (1880-) Irish and Italians Prejudice and discrimination toward Catholics Chinese and Japanese Chinese Exclusion Act, Alien Land Act Japanese internment during WWII 3 WWII through 1970’s: A positive environment with a demand for laborers. Immigrants were welcomed. 1970-1990: Oil crisis, followed by economic globalization. Immigrants were seen as threat to US economy. e.g. Killing of Vincent Chen 4 1990-2000: Immigrants from Eastern Europe after the break down of the former Soviet Union 2001- : Immigrants from Middle East 5 Ambivalent Attitude toward Immigrants The sympathy and antipathy that individuals express toward these groups is hypothesized to be due to two strong, but conflicting American values (Biernat, et al., 1996; Katz & Haas, 1988). Egalitarianism and Protestant Work Ethic 6 Americans value egalitarianism, characterized by social equality, social justice, and concern for others in need. Americans also value the Protestant Work Ethic (PWE), an individualistic belief in hard work, self-discipline, and individual achievement. e.g. Protestant Work Ethic and Development of Capitalism (Max Weber) 7 Egalitarianism is negatively associated with all forms of prejudice, whereas adherence to the PWE is positively associated with prejudice toward those outgroups viewed to violate the PWE (Biernat et al.1996) . -

On Human Migration and the Moral Obligations of Business Linda H

UNF Digital Commons UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations Student Scholarship 2008 On Human Migration and the Moral Obligations of Business Linda H. Harris University of North Florida Suggested Citation Harris, Linda H., "On Human Migration and the Moral Obligations of Business" (2008). UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations. 296. https://digitalcommons.unf.edu/etd/296 This Master's Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at UNF Digital Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in UNF Graduate Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of UNF Digital Commons. For more information, please contact Digital Projects. © 2008 All Rights Reserved On Human Migration and the Moral Obligations of Business by Linda H. Harris A thesis submitted to the Department of Philosophy in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Masters of Practical Philosophy and Applied Ethics UNIVERSITY OF NORTH FLORIDA COLLEGE OF ARTS AND SCIENCES December, 2008 MASTERS THESIS COMPLETION FORM This document attests that the written and oral requirements of the MA thesis on Practical Philosophy and Applied Ethics, including submission of a written essay and a public oral defense, have been fulfilled. Student's Name: Linda H. Harris ID # N00437707 Semester: Fall Year: 2008 Date: November 7 THESIS TITLE: On Human Migration and the Moral Obligations of Business Signature Deleted MEMBERS OF THE THESIS COMMITTEE: Signature Deleted Signature Deleted Signature Deleted Approved by Graduate Coordinator Signature Deleted Signature Deleted Approved by Signature Deleted Approved by cfa{!Uate School For my Sons ubi amor, ibi patria Acknowledgements Dickie, there are occasions when words are not enough. -

Attitudes Toward Asian Americans: Developing a Prejudice Scale

University of Massachusetts Amherst ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 1999 Attitudes toward Asian Americans: developing a prejudice scale. Monica H. Lin University of Massachusetts Amherst Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses Lin, Monica H., "Attitudes toward Asian Americans: developing a prejudice scale." (1999). Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014. 2333. Retrieved from https://scholarworks.umass.edu/theses/2333 This thesis is brought to you for free and open access by ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses 1911 - February 2014 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UMass Amherst. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ATTITUDES TOWARD ASIAN AMERICANS: DEVELOPING A PREJUDICE SCALE A Thesis Presented by MONICA H. LIN Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Massachusetts Amherst in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of MASTER OF SCIENCE February 1999 Psychology © Copyright by Monica Han-Chun Lin 1999 All Rights Reserved ATTITUDES TOWARD ASIAN AMERICANS: DEVELOPING A PREJUDICE SCALE A Thesis Presented by MONICA H. LIN Approved as to style and content by: Susan T. Fiske, Chair Icek Aizen, Member n tephenson, Member Melinda Novak, Department Chair Department of Psychology ACKNOWLEDGMENTS Throughout my graduate career, I received generous financial support from a University of Massachusetts Minority Scholar Fellowship, a National Institute of Mental Health training grant, an American Psychological Association Minority Fellowship in Research Training, and a National Science Foundation grant awarded to Susan Fiske. A fellowship presented by the Institute for Asian American Studies at the University of Massachusetts in Boston provided additional funding for data collection. -

PROFESSIONAL AGEISM: the Impact of Ageism Among Research and Healthcare Professionals on Older Patients: a Systematic Review

PROFESSIONAL AGEISM: The Impact of Ageism among Research and Healthcare Professionals on Older Patients: A Systematic Review The Impact of Ageism among Legal and Financial Professionals on Older People: Systematised Reviews Susan Markham A thesis in fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science (Research) School of Psychiatry Faculty of Medicine September 2020 1 Thesis Title PROFESSIONAL AGEISM: The Impact of Ageism among Research and Healthcare Professionals on Older Patients: A Systematic Review The Impact of Ageism among Legal and Financial Professionals on Older People: Systematised Reviews ABSTRACT Ageism – stereotyping, prejudice and discrimination towards people on the basis of chronological age – is ubiquitous in society and has a significant impact on older people across many aspects of their lives, including the provision of critical services. However, the impact of ageist behaviours on the part of key frontline professionals who interact closely and regularly with older people – healthcare, legal and financial professionals – has never been synthesised. Aim: The aim of this project was to examine how ageism influences professional behaviour among these providers and subsequently affects outcomes for older people. The overall hypothesis was that ageist actions and decisions by healthcare, legal and financial professionals would adversely impact the care and management of older people, including the provision of clinical care, services and advice. Methods: The project involved three components: a systematic review of the medical literature (the major component) and two systematised reviews of the legal and financial literature. The systematic review of the medical literature was conducted in accordance with the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analysis (PRISMA) guidelines in order to identify, evaluate and synthesise research focusing on age-based actions by research and healthcare professionals and consequences for older patients. -

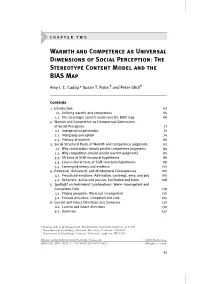

The Stereotype Content Model and the BIAS Map

CHAPTER TWO Warmth and Competence as Universal Dimensions of Social Perception: The Stereotype Content Model and the BIAS Map Amy J. C. Cuddy,* Susan T. Fiske,† and Peter Glick‡ Contents 1. Introduction 62 1.1. Defining warmth and competence 65 1.2. The stereotype content model and the BIAS map 66 2. Warmth and Competence as Fundamental Dimensions of Social Perception 71 2.1. Interpersonal perception 71 2.2. Intergroup perception 74 2.3. Primacy of warmth 89 3. Social Structural Roots of Warmth and Competence Judgments 93 3.1. Why social status should predict competence judgments 94 3.2. Why competition should predict warmth judgments 95 3.3. US tests of SCM structural hypotheses 96 3.4. Cross-cultural tests of SCM structural hypotheses 99 3.5. Converging theory and evidence 101 4. Emotional, Behavioral, and Attributional Consequences 102 4.1. Prejudiced emotions: Admiration, contempt, envy, and pity 102 4.2. Behaviors: Active and passive, facilitation and harm 108 5. Spotlight on Ambivalent Combinations: Warm–Incompetent and Competent–Cold 119 5.1. Pitying prejudice: Warm but incompetent 120 5.2. Envious prejudice: Competent but cold 125 6. Current and Future Directions and Summary 130 6.1. Current and future directions 130 6.2. Summary 137 * Kellogg School of Management, Northwestern University, Evanston, IL 60208 { Department of Psychology, Princeton University, Princeton, NJ 08540 { Department of Psychology, Lawrence University, Appleton, WI 54912 Advances in Experimental Social Psychology, Volume 40 # 2008 Elsevier Inc. ISSN 0065-2601, DOI: 10.1016/S0065-2601(07)00002-0 All rights reserved. 61 62 Amy J. C. -

Kite & Whitley 3E, Long Toc, P. 1 Long Table of Contents Chapter 1

Kite & Whitley 3e, Long ToC, p. 1 Long Table of Contents Chapter 1: Introducing the Concepts of Stereotyping, Prejudice, and Discrimination Race and Culture Historical Views of Ethnic Groups Cultural Influences on Perceptions of Race and Ethnicity Group Privilege Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Discrimination Stereotypes Prejudice Discrimination Interpersonal discrimination Organizational discrimination Institutional discrimination Cultural discrimination The Relationships among Stereotyping, Prejudice, and Discrimination Targets of Prejudice Racism Gender and Sexual Orientation Age, Ability, and Appearance Classism Religion Theories of Prejudice and Discrimination Scientific Racism Kite & Whitley 3e, Long ToC, p. 2 Psychodynamic Theory Sociocultural Theory Intergroup Relations Theory Cognitive Theory Evolutionary Theory Where Do We Go from Here? Summary Suggested Readings Key Terms Questions for Review and Discussions Chapter 2: How Psychologists Study Prejudice and Discrimination Formulating Hypotheses Measuring Stereotypes, Prejudice, and Discrimination Reliability and Validity Self-Report Measures Assessing stereotypes Assessing prejudice Assessing behavior Advantages and limitations Unobtrusive Measures Physiological Measures Implicit Cognition Measures Self-Report versus Physiological and Implicit Cognition Measures Using Multiple Measures Kite & Whitley 3e, Long ToC, p. 3 Research Strategies Correlational Studies Survey research The correlation coefficient Correlation and causality Experiments Experimentation and causality Laboratory -

Ambivalent Homoprejudice Towards Gay Men

AMBIVALENT HOMOPREJUDICE TOWARDS GAY MEN Ambivalent Homoprejudice towards Gay Men: Theory Development and Validation Ashley S. Brooks, PhD.1 Russell Luyt, PhD.2 Magdalena Zawisza, PhD.1 Daragh T. McDermott, PhD.1 1Anglia Ruskin University 2 University of Greenwich Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Ashley S. Brooks (email: [email protected]) or Daragh T. McDermott (email: [email protected]) AMBIVALENT HOMOPREJUDICE TOWARDS GAY MEN Abstract Myriad social groups are targets of hostile and benevolent (i.e., ambivalent) prejudice. However, prejudice towards gay men is typically conceptualised as hostile, despite the prevalence of benevolence towards gay men in popular media. This paper aims to compare gay men with other targets of ambivalent prejudice (i.e., women and elderly people), and draw upon the stereotype content and microaggressions literatures in order to develop a theory of ambivalent homoprejudice. The resultant framework, comprising repellent; adversarial; romanticised; and paternalistic homoprejudice was investigated using seven focus groups of heterosexuals and gay men (N = 22) and the findings were consistent with stereotype content theory. Directions for future research into the deleterious effects of ambivalent Homoprejudice and possible empowering interventions are discussed. Key words: Ambivalence, Prejudice, Gay Men, Attitudes, Stereotype Content AMBIVALENT HOMOPREJUDICE TOWARDS GAY MEN “Have you guessed the must-have accessory every woman needs? I’ve got one, so does Linda and Martine, Janet’s got several actually – coming out of her ears, sometimes! What am I talking about? A G.B.F.: A gay best friend.” – Ruth Langsford, Loose Women, ITV Studios (2016) Decades ago, it might have seemed unthinkable that a popular daytime television show such as Loose Women would discuss the topic of homosexuality so openly – let alone in such an admiring manner. -

Beyond Prejudice: Are Negative Evaluations the Problem and Is Getting Us to Like One Another More the Solution?

BEHAVIORAL AND BRAIN SCIENCES (2012) 35, 411–466 doi:10.1017/S0140525X11002214 Beyond prejudice: Are negative evaluations the problem and is getting us to like one another more the solution? John Dixon Department of Psychology, Open University, Milton Keynes MK7 6AA, United Kingdom [email protected] http://www.open.ac.uk/socialsciences/staff/people-profile.php?name= John_Dixon Mark Levine Department of Psychology, Exeter University, Exeter, Devon EX4 4SB, United Kingdom [email protected] http://psychology.exeter.ac.uk/staff/index.php?web_id=Mark_Levine Steve Reicher School of Psychology, St Andrews University, St Andrews KY16 9JP, United Kingdom [email protected] http://psy.st-andrews.ac.uk/people/lect/sdr.shtml Kevin Durrheim School of Psychology, University of KwaZulu-Natal, Pietermaritzburg, 3209, South Africa [email protected] http://psychology.ukzn.ac.za/staff.aspx Abstract: For most of the history of prejudice research, negativity has been treated as its emotional and cognitive signature, a conception that continues to dominate work on the topic. By this definition, prejudice occurs when we dislike or derogate members of other groups. Recent research, however, has highlighted the need for a more nuanced and “inclusive” (Eagly 2004) perspective on the role of intergroup emotions and beliefs in sustaining discrimination. On the one hand, several independent lines of research have shown that unequal intergroup relations are often marked by attitudinal complexity, with positive responses such as affection and admiration mingling with negative responses such as contempt and resentment. Simple antipathy is the exception rather than the rule. On the other hand, there is mounting evidence that nurturing bonds of affection between the advantaged and the disadvantaged sometimes entrenches rather than disrupts wider patterns of discrimination. -

The Role of Threat, Emotion, and Individual Difference Characteristics in Attitudes and Perceptions of Minority Groups

The University of Maine DigitalCommons@UMaine Honors College Spring 5-2017 The Role of Threat, Emotion, and Individual Difference Characteristics in Attitudes and Perceptions of Minority Groups Aeleah Granger University of Maine Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors Part of the Psychology Commons Recommended Citation Granger, Aeleah, "The Role of Threat, Emotion, and Individual Difference Characteristics in Attitudes and Perceptions of Minority Groups" (2017). Honors College. 305. https://digitalcommons.library.umaine.edu/honors/305 This Honors Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by DigitalCommons@UMaine. It has been accepted for inclusion in Honors College by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@UMaine. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ROLE OF THREAT, EMOTION, AND INDIVIDUAL DIFFERENCE CHARACTERISTICS IN ATTITUDES AND PERCEPTIONS OF MINORITY GROUPS by Aeleah M. Granger A Thesis Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for a Degree with Honors (Psychology) The Honors College University of Maine May 2017 Advisory Committee Jordan P. LaBouff, Associate Professor of Psychology and Honors Shannon McCoy, Associate Professor of Psychology, Interim Director Rising Tide Thane Fremouw, Associate Professor of Psychology Jennie Woodard, Adjunct instructor of History, Women’s, Gender, and Sexuality Studies and Honors Amy Fried, Professor and Chair of Political Science Abstract A socio-functional approach to prejudice posits that different out-groups are perceived to pose different types of threats to group success by in-group members. These different types of threats include physical safety/security threats, economic threats, moral threats, etc. Within this framework, each type of threat elicits a different emotional response from in-group members.