From Detroit to Deir Dibwan

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

View Daily Report

Israeli Violations' Activities in the oPt 16 May 2017 The daily report highlights the violations behind Israeli home demolitions and demolition threats The Violations are based on in the occupied Palestinian territory, the reports provided by field workers confiscation and razing of lands, the uprooting and\or news sources. and destruction of fruit trees, the expansion of settlements and erection of outposts, the brutality The text is not quoted directly of the Israeli Occupation Army, the Israeli settlers from the sources but is edited for violence against Palestinian civilians and clarity. properties, the erection of checkpoints, the The daily report does not construction of the Israeli segregation wall and necessarily reflect ARIJ’s opinion. the issuance of military orders for the various Israeli purposes. Brutality of the Israeli Occupation Army • A Palestinian fisherman who was shot and injured by Israeli occupation Army (IOA) off the coast of the besieged Gaza Strip earlier succumbed to his wounds. Muhammad Majid Bakr, a 23-year-old resident from the al-Shati refugee camp, was shot by Israeli naval forces at around 8:30 a.m. on Monday morning while fishing off the coast of Gaza with his brother Umran Majid Bakr. He had been shot in the chest, and was still bleeding when Israeli naval ships surrounded their fishing boat and detained Bakr. (Maannews 16 May 2017) 1 • Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) broke into a blacksmith workshop in Deir al-Ghosun town near Tulkarem city and confiscated its machinery and equipment before closing the workshop. (PALINFO 16 May 2017) • Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) detained three Palestinian fishermen off the coast of Al-Sudaniyeh, northwest of Gaza city. -

A History of Money in Palestine: from the 1900S to the Present

A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present The Harvard community has made this article openly available. Please share how this access benefits you. Your story matters Citation Mitter, Sreemati. 2014. A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present. Doctoral dissertation, Harvard University. Citable link http://nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:12269876 Terms of Use This article was downloaded from Harvard University’s DASH repository, and is made available under the terms and conditions applicable to Other Posted Material, as set forth at http:// nrs.harvard.edu/urn-3:HUL.InstRepos:dash.current.terms-of- use#LAA A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present A dissertation presented by Sreemati Mitter to The History Department in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the subject of History Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts January 2014 © 2013 – Sreemati Mitter All rights reserved. Dissertation Advisor: Professor Roger Owen Sreemati Mitter A History of Money in Palestine: From the 1900s to the Present Abstract How does the condition of statelessness, which is usually thought of as a political problem, affect the economic and monetary lives of ordinary people? This dissertation addresses this question by examining the economic behavior of a stateless people, the Palestinians, over a hundred year period, from the last decades of Ottoman rule in the early 1900s to the present. Through this historical narrative, it investigates what happened to the financial and economic assets of ordinary Palestinians when they were either rendered stateless overnight (as happened in 1948) or when they suffered a gradual loss of sovereignty and control over their economic lives (as happened between the early 1900s to the 1930s, or again between 1967 and the present). -

November 2014 Al-Malih Shaqed Kh

Salem Zabubah Ram-Onn Rummanah The West Bank Ta'nak Ga-Taybah Um al-Fahm Jalameh / Mqeibleh G Silat 'Arabunah Settlements and the Separation Barrier al-Harithiya al-Jalameh 'Anin a-Sa'aidah Bet She'an 'Arrana G 66 Deir Ghazala Faqqu'a Kh. Suruj 6 kh. Abu 'Anqar G Um a-Rihan al-Yamun ! Dahiyat Sabah Hinnanit al-Kheir Kh. 'Abdallah Dhaher Shahak I.Z Kfar Dan Mashru' Beit Qad Barghasha al-Yunis G November 2014 al-Malih Shaqed Kh. a-Sheikh al-'Araqah Barta'ah Sa'eed Tura / Dhaher al-Jamilat Um Qabub Turah al-Malih Beit Qad a-Sharqiyah Rehan al-Gharbiyah al-Hashimiyah Turah Arab al-Hamdun Kh. al-Muntar a-Sharqiyah Jenin a-Sharqiyah Nazlat a-Tarem Jalbun Kh. al-Muntar Kh. Mas'ud a-Sheikh Jenin R.C. A'ba al-Gharbiyah Um Dar Zeid Kafr Qud 'Wadi a-Dabi Deir Abu Da'if al-Khuljan Birqin Lebanon Dhaher G G Zabdah לבנון al-'Abed Zabdah/ QeiqisU Ya'bad G Akkabah Barta'ah/ Arab a-Suweitat The Rihan Kufeirit רמת Golan n 60 הגולן Heights Hadera Qaffin Kh. Sab'ein Um a-Tut n Imreihah Ya'bad/ a-Shuhada a a G e Mevo Dotan (Ganzour) n Maoz Zvi ! Jalqamus a Baka al-Gharbiyah r Hermesh Bir al-Basha al-Mutilla r e Mevo Dotan al-Mughayir e t GNazlat 'Isa Tannin i a-Nazlah G d Baqah al-Hafira e The a-Sharqiya Baka al-Gharbiyah/ a-Sharqiyah M n a-Nazlah Araba Nazlat ‘Isa Nazlat Qabatiya הגדה Westהמערבית e al-Wusta Kh. -

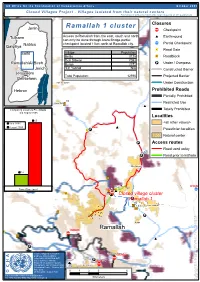

Ramallah 1 Cluster Closures Jenin ‚ Checkpoint

D UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs October 2005 º¹P Closed Villages Project - Villages isolated from their natural centers º¹P Palestinians without permits (the large majority of the population) /" ## Ramallah 1 cluster Closures Jenin ¬Ç Checkpoint ## Tulkarm AccessSalfit to Ramallah from the east, south and north Earthmound can only be done through Atara Bridge partial ¬Ç Nablus checkpoint located 11km north of Ramallah city. Partial Checkpoint Qalqiliya D Road## Gate Salfit Village Population Beitin 3125 /" Roadblock Deir Dibwan 7093 º¹ Ramallah/Al Bireh Burqa 2372 P Under / Overpass 'Ein Yabrud N/A ## Jericho ### Constructed Barrier Jerusalem Total Population: 12590 ## Projected Barrier Bethlehem ## Deir as Sudan Deir as Sudan ## Under Construction ## Hebron Prohibited Roads C /" An Nabi Salih Partially Prohibited ¬Ç ## 15 Umm Safa/" Restricted Use ## # # Comparing situations Pre-Intifada Totally Prohibited and August 2005 Localities 65 Year 2000 <all other values> August 2005 Atara ## D ¬Çº¹P Palestinian localities Natural center º¹P Access routes Road used today 11 12 ##º¹P/" Road prior to Intifada 'Ein'Ein YabrudYabrud 12 /" /" 10 At Tayba /" 9 Beitin Ç Travel Time (min) DCO 2 D ¬ /"Ç## /" ¬/"3 ## 1 Closed village cluster Ramallahº¹P 1 42 /" 43 Deir Dibwan /" /" º¹P the part of the the of part the Burqa Ramallah delimitation the concerning D ¬Ç Beituniya /" ## º¹DP Closure mapping is a work in Qalandiya QalandiyaCamp progress. Closure data is Ç collected by OCHA field staff º¹ ¬ Beit Duqqu and is subject to change. P Atarot 144 Maps will be updated regularly. ### ¬Ç Cartography: OCHA Humanitarian 170 Al Judeira Information Centre - October 2005 Al Jib Beit 'Anan ## Bir Nabala Base data: Al 036Jib 12 O C H A O C H OCHA updateBeit AugustIjza 2005 losedFor comments village contact <[email protected]> cluster # # Tel. -

Israeli Violations' Activities in the Opt 19 November 2018

Israeli Violations' Activities in the oPt 19 November 2018 The daily report highlights the violations behind Israeli home demolitions and demolition threats The Violations are based on in the occupied Palestinian territory, the reports provided by field workers confiscation and razing of lands, the uprooting and\or news sources. and destruction of fruit trees, the expansion of The text is not quoted directly settlements and erection of outposts, the brutality from the sources but is edited for of the Israeli Occupation Army, the Israeli settlers clarity. violence against Palestinian civilians and properties, the erection of checkpoints, the The daily report does not construction of the Israeli segregation wall and necessarily reflect ARIJ’s opinion. the issuance of military orders for the various Israeli purposes. Brutality of the Israeli Occupation Army • The Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) invaded the al-Mazra’a al- Gharbiyya village, northwest of Ramallah, before detaining Bassel Ladawda, and the head of Birzeit University Students’ Council, Yahia Rabea’. (IMEMC 19 November 2018) • The Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) invaded Deir Abu Mash’al, and fired many live rounds, rubber-coated steel bullets, gas bombs and 1 concussion grenades, at local youngsters who protested the invasion. The IOA searched homes in Deir Abu Mash’al village, west of Ramallah, and detained Omar Mahmoud Rabea’. The IOA fired live rounds at a Palestinian car in the village, wounding four residents including one who suffered a serious injury. (IMEMC 19 November 2018) Israeli Arrests • In Nablus, the Israeli Occupation Army (IOA) detained Ezzeddin Marshoud, Mahmoud Faisal Qawareeq, Anas Eshteyya and Nasr Shreim. -

Annual Report #4

Fellow engineers Annual Report #4 Program Name: Local Government & Infrastructure (LGI) Program Country: West Bank & Gaza Donor: USAID Award Number: 294-A-00-10-00211-00 Reporting Period: October 1, 2013 - September 30, 2014 Submitted To: Tony Rantissi / AOR / USAID West Bank & Gaza Submitted By: Lana Abu Hijleh / Country Director/ Program Director / LGI 1 Program Information Name of Project1 Local Government & Infrastructure (LGI) Program Country and regions West Bank & Gaza Donor USAID Award number/symbol 294-A-00-10-00211-00 Start and end date of project September 30, 2010 – September 30, 2015 Total estimated federal funding $100,000,000 Contact in Country Lana Abu Hijleh, Country Director/ Program Director VIP 3 Building, Al-Balou’, Al-Bireh +972 (0)2 241-3616 [email protected] Contact in U.S. Barbara Habib, Program Manager 8601 Georgia Avenue, Suite 800, Silver Spring, MD USA +1 301 587-4700 [email protected] 2 Table of Contents Acronyms and Abbreviations …………………………………….………… 4 Program Description………………………………………………………… 5 Executive Summary…………………………………………………..…...... 7 Emergency Humanitarian Aid to Gaza……………………………………. 17 Implementation Activities by Program Objective & Expected Results 19 Objective 1 …………………………………………………………………… 24 Objective 2 ……………………................................................................ 42 Mainstreaming Green Elements in LGI Infrastructure Projects…………. 46 Objective 3…………………………………………………........................... 56 Impact & Sustainability for Infrastructure and Governance ……............ -

Deir Dibwan Town Profile

Deir Dibwan Town Profile Prepared by The Applied Research Institute – Jerusalem Funded by Spanish Cooperation 2012 Palestinian Localities Study Ramallah Governorate Acknowledgments ARIJ hereby expresses its deep gratitude to the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID) for their funding of this project. ARIJ is grateful to the Palestinian officials in the ministries, municipalities, joint services councils, village committees and councils, and the Palestinian Central Bureau of Statistics (PCBS) for their assistance and cooperation with the project team members during the data collection process. ARIJ also thanks all the staff who worked throughout the past couple of years towards the accomplishment of this work. 1 Palestinian Localities Study Ramallah Governorate Background This report is part of a series of booklets, which contain compiled information about each city, town, and village in the Ramallah Governorate. These booklets came as a result of a comprehensive study of all localities in Ramallah Governorate, which aims at depicting the overall living conditions in the governorate and presenting developmental plans to assist in developing the livelihood of the population in the area. It was accomplished through the "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment;" the project funded by the Spanish Agency for International Cooperation for Development (AECID). The "Village Profiles and Needs Assessment" was designed to study, investigate, analyze and document the socio-economic conditions and the needed programs and activities to mitigate the impact of the current unsecure political, economic and social conditions in Ramallah Governorate. The project's objectives are to survey, analyze, and document the available natural, human, socioeconomic and environmental resources, and the existing limitations and needs assessment for the development of the rural and marginalized areas in Ramallah Governorate. -

13-26 July 2021

13-26 July 2021 Latest developments (after the reporting period) • On 28 July, Israeli forces shot and killed an 11-year-old Palestinian boy who was in a car with his father at the entrance of Beit Ummar (Hebron). According to the Israeli military, soldiers ordered a driver to stop and, after he failed to do so, they shot at the vehicle, reportedly aiming at the wheels. On 29 July, following protests at the funeral of the boy, during which Palestinians threw stones Israeli forces soldiers shot live ammunition, rubber bullets and tear gas canisters, shooting and killing one Palestinian. • On 27 July, Israeli forces shot and killed a 41-year-old Palestinian at the entrance of Beita (Nablus). According to the military, the man was walking towards the soldiers, holding an iron bar, and did not stop after they shot warning fire. No clashes were taking place at that time. Highlights from the reporting period • Two Palestinians, including a boy, died after being shot by Israeli forces during the reporting period. Israeli forces entered An Nabi Salih (Ramallah) to carry out an arrest operation, and when Palestinian residents threw stones at them, soldiers shot live ammunition and tear gas canisters. During this exchange of fire, Israeli forces shot and killed a 17-year-old boy, who, according to the military, was throwing stones and endangered the life of soldiers. According to Palestinian sources, he was shot in his back. On 26 July, a Palestinian died of wounds after being shot by Israeli forces on 14 May, in Sinjil (Ramallah), during clashes between Palestinians and Israeli forces. -

Public Perceptions and Knowledge Towards Wastewater Reuse in Agriculture in Deir Debwan

First Symposium on Wastewater Reclamation and Reuse for Water Demand Management in Palestine, 2-3 April 2008, Birzeit University, Palestine Public Perceptions and Knowledge towards Wastewater Reuse in Agriculture in Deir Debwan Maher Abu-Madi*, Ziad Mimi*, and Niveen Abu-Rmeileh** *Institute of Environmental and Water Studies, Birzeit University, Palestine E-mail: [email protected] **Institute of Community and Public Health, Birzeit University, Palestine Abstract The Occupied Palestinian Territory is facing a rapid population growth with limited water resources. The continuous demand for water forces Palestinians to look for alternative water recourses. Wastewater reuse in agriculture is one of the strategic alternatives. A cross sectional survey took place in one of Ramallah villages to investigate people’s perception toward wastewater reuse in agriculture in 2007. Over all, participants had good knowledge about the general water crisis, 93 % were aware of the water crisis in Palestine, and 90 % were aware of water crisis in their village. Interestingly, 73 % knew that there are negative impacts from using untreated wastewater in irrigation and 24% knew that there are negative impacts from using treated wastewater. Further, only 40 % knew that there are special standards for wastewater reuse and 42 % did not know if there should be special standards for wastewater reuse. It was obvious that participants are willing to use treated wastewater (87 %) and products irrigated with it (85 %). However, the situation was opposite concerning untreated wastewater with only 6 % are willing to use it and 10 % are willing to use products irrigated with it. Health was the main reason followed by environmental and economical reasons for not accepting the reuse of wastewater. -

Ibrahim Muhawi

Ibrahim Muhawi Centerfor CorrtemporaryArab Str-;clies EdlnundA WalshSchrool cf FcreiqrrSetrvir-e Georq ctc-rwn U n itrr-' rsity (O2CC9 Contextsof Languagein MahmoudDarwish lbrahim Muhawi Ibrahim Muharvirvits born in llamallah,Palestine, ancl receivecl his higherecti- catiotritr lrnglishliterature at the Universityof'California. l{e hastirtrght at ur-ri- versitiesin Clanacia,the .lvlidcllellast, North Africa, lhe UnitetlStates, Scotiaitd, atrd(ierman,v. He is the authol of a nurnberof booksand articlcsrln l)alestinian arndArabic folkloreand literatrLre,including (rvith Sharif'l(anaana) Spcak, Birrl, SpetrkA{oin: PolestininnAralt Folktttlcs(i989) ancl(rvith Yasir Suleinran) Litcro- tureand licttittt'tin thc NliticlleEnst (2006). Fle is alsothc translutor<>f iv'lolrmoud I)orv'islish4etrtorl'_f or I:orgct-firlircss(199-5) and Zakar"ia'lanrer's Ilreokire Knccs (2008),andis cr-rrrcntlynorking on a trauslationol I)arlvish'sltturrral of'rut Or- riinary Grie/. 'Ihis patrrerwas eclitt'db,v N1inri Kirlt ancl'l'rarriss (lassidv ils a pilper lr'onrits origir-ralfbrmat irsa 20-rninutetall<, gir.,e n on the occasior-ro1- a tributeto thc lif'c atrdrvorli of N'lal'rrrouci[)aru'ish. IBRAHIMMUHAWI Center for Contemporary Arab Studies EdmundA.Walsh Schoolof ForeignService 241 Intercultural Center Georgetown University Washington, D.C. 20057- 1020 202.687.5793 http ://ccas.georgetown. edu @2009 by the Center for Contemporary Arab Studies. Atl rights reserved. CONTEXTSOF LANGUACEIN MAHMOUDDARWISH MahmoudDarwish was born in Al-Birweh,Palestine, in 1942.With -

2016 Annual Report

member of World Service Jerusalem 2016 Annual Report Foreword | 1-6 Augusta Victoria Hospital (AVH) | 7-23 Serious Medicine, Caring Staff |7 Ribbon Cutting Ceremony Marks Reopening of Surgical Department | 8 Restoring Hope and Reviving Dreams: New Bone Marrow Transplantation Unit Officially Opened 9| Refurbished Diabetes Care Center Serves Community | 10-11 Mobile Mammography Unit Promotes Awareness, Education, and Early Detection | 12-13 AVH Experience in Elder Care and Palliative Medicine Provides Solid Basis for Expanding Its Services | 14-15 Diverse Specialists Bring to Life the AVH Motto, “Serious Medicine...Caring Staff” |16-17 New AVH School Provides Continuation of Education for Children with Chronic Illnesses | 18 Contents AVH Patient Assistance Fund | 19 AVH Participates in “Clean Care is Safer Care” Initiative | 20 Volunteer Hospitality Program at AVH Fosters Welcoming Atmosphere | 21 AVH Statistics 2016 | 22 AVH Board of Governance | 23 Map of LWF Jerusalem Program Activities | 24-25 Vocational Training Program (VTP) | 26-40 Empowering Youth, Building Civil Society | 26 LWF Vocational Training Program Data 2016 | 27 VTP Graduates Take Varied Paths to Sustainable Livelihoods | 28-30 Table of of Table LWF Opens Multi-Purpose Sports Field at Vocational Training Center in East Jerusalem | 31-32 LWF Summer Camp in Beit Hanina Provides Career Orientation for East Jerusalem Youth | 33-34 Yousef Shalian Offers Professional, Visionary Leadership |34-36 LWF VTP 2016 Graduates Employment Statistics | 37-39 Vocational Training Advisory -

National Report, State of Palestine United Nations

National Report, State of Palestine United Nations Conference on Human Settlements (Habitat III) 2014 Ministry of Public Works and Housing National Report, State of Palestine, UN-Habitat 1 Photo: Jersualem, Old City Photo for Jerusalem, old city Table of Contents FORWARD 5 I. INTRODUCTION 7 II. URBAN AGENDA SECTORS 12 1. Urban Demographic 12 1.1 Current Status 12 1.2 Achievements 18 1.3 Challenges 20 1.4 Future Priorities 21 2. Land and Urban Planning 22 2. 1 Current Status 22 2.2 Achievements 22 2.3 Challenges 26 2.4 Future Priorities 28 3. Environment and Urbanization 28 3. 1 Current Status 28 3.2 Achievements 30 3.3 Challenges 31 3.4 Future Priorities 32 4. Urban Governance and Legislation 33 4. 1 Current Status 33 4.2 Achievements 34 4.3 Challenges 35 4.4 Future Priorities 36 5. Urban Economy 36 5. 1 Current Status 36 5.2 Achievements 38 5.3 Challenges 38 5.4 Future Priorities 39 6. Housing and Basic Services 40 6. 1 Current Status 40 6.2 Achievements 43 6.3 Challenges 46 6.4 Future Priorities 49 III. MAIN INDICATORS 51 Refrences 52 Committee Members 54 2 Lists of Figures Figure 1: Percent of Palestinian Population by Locality Type in Palestine 12 Figure 2: Palestinian Population by Governorate in the Gaza Strip (1997, 2007, 2014) 13 Figure 3: Palestinian Population by Governorate in the West Bank (1997, 2007, 2014) 13 Figure 4: Palestinian Population Density of Built-up Area (Person Per km²), 2007 15 Figure 5: Percent of Change in Palestinian Population by Locality Type West Bank (1997, 2014) 15 Figure 6: Population Distribution