Sinbad in the Rented World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Winter 2011 – 12 December 2011 – March 2012 OVERVIEW Winter at the Power Plant

exhibitions / programs / events Winter 2011 – 12 December 2011 – March 2012 OVERVIEW Winter at The Power Plant Our Winter season presents two major The evening before the opening of the Winter exhi- exhibitions that delve into a wellspring bitions, Stan Douglas will speak in our International Lecture Series (8 December), while the influential of cultural history and the archive of artist Martha Rosler will give an ILS presentation a the social. week later, on 15 December. In the new year, in addition to a lecture by participating artist Stan Douglas: Entertainment features selections Christian Holstad, Coming After extends into a from the Vancouver artist’s outstanding new series of live events and film programs co-present- photographic project Midcentury Studio, in which ed with the Feminist Art Gallery and the Art Gallery Douglas assumes the lens of a postwar photogra- of York University, in tandem with their retrospec- pher as he takes on various jobs from photojour- tive of the late Toronto artist Will Munro. nalism to advertising. The exhibition includes In addition, we are pleased to collaborate with images of novelties and divertissements, as well as World Stage, Harbourfront Centre’s international his Malabar People suite of portraits of the performing arts series for the theatrical run of denizens of a fictional nightclub. The bars, clubs Everything Under the Moon by Toronto artist Shary and bathhouses that appear in the work in the Boyle (who had a solo exhibition at The Power Plant group exhibition Coming After, however, are in 2006) and Winnipeg musician Christine Fellows, absent of revelers — as if the party is over. -

Wm- F*Ac*Mi*I J I AUGUST 12 AUGUST 161 AUGUST 19 FRIDAY AUGUST 201 77K HEY MIGHT E GIANTS Flilagess-Vogcte! SPINE on the HIGHWAY TOUR

;&;..—,>'• r..- :y „o Wm- F*Ac*Mi*i J I AUGUST 12 AUGUST 161 AUGUST 19 FRIDAY AUGUST 201 77k HEY MIGHT E GIANTS flilAGESS-VOGCte! SPINE ON THE HIGHWAY TOUR RY DJS PANDEMONH MALEflCENT - AND HSR BAND I RICHARD'S ON RICHARDS I I COMMODORE BALLROOM | | COMMODORE BALLROOM FRIDAY SEPTEMBER 31 1 SFPTEMBERTI I SEPTEMBER 7 BURJNI1NG factfto face SPEAR TOOTS AND THE- PINCH ^l»W&t* I I •COVE [TOUNTERFIT AND GUESTS MY CHEMICAL ROMANCE Conce. itember 51 BETA FACTOR B IS TICKETS ALSO AT SATURDAYS ZULU AND SCRATCH MALKIN BOWL, DOORS 7PM, SHOW 8PM t<Pr^ I ALL AGES IC8MMIIDME BSLLBOOM | IAN CULTURAL CEN I SEPTEMBER!?! fsiEPTEMBER2B| ^^MoJ^^^^^^Sy. momGRum TJLl m>J!'Z ev£~*4%S0i WmMMi ITHOUTYOU I mmmxtmn I CROATIAN CULTURAL CENTRE 1 I COMMODORE BALLROOM I WKBm SNOWj "*sarah IHSIDEIJUDOMMY^I ATR PI Jrarmer ECOBIBING with Josh ritter limp*: SEPTEMBER 28 ->mm October 16 RICHARD'S SEPTEMBER 27 ON RICHARDS COMMODORE OCTOBER 18 BALLROOM COMMODORE BALLROOM TICKETS ALSO AT ZULU PURCHASE TICKETS SQQGOO AT hob,com OR ticketmaster.ca ticUetmaster604-280-44427y SCREW THE REST, THIS IS THE REAL DEAL THAT "WHY YOU DIDN'T MIL ME?"MAGAZINE FROM CiTR 101.9FM EDITglX i-M Siddle ADMAN Jason Bennet FEATURES Attention all bands, PRODUCTION MANAGER BaserrlffiiT Sweets p.9 musicians, drumming monkeys! Blimp.10 ART DIRECTOR Fake Cops p. 11 Dale Davies ^^pder the Volcano pvl2 EDITORIAQKSSISTANT ^S^ei^^cording p. 13 TA EDITOR r^3j|^^pyra DraciMfic!/'"^ REGULARS FroT*rM®£) lsk of... S^ JI^EDITOR t mm ^;^uckj|(g|BlwIls1nit pjife |? LAYOUT & DESIGN -Dale Davies fff^iff I^Hp ^t^Saeme Worthy '^'|rextUal^^tjve p.8 ^^^on ^iisflliiif&b Underlf^^^vsf p^^" l^^^py^Draculem §||f|§y & rat (big tim|| Real Live Action p. -

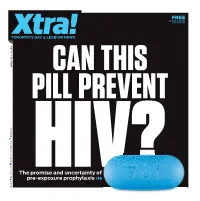

The Promise and Uncertainty of Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis

FREE 36,000 AUDITED CIRCULATION TORONTO’S GAY & LESBIAN NEWS FEB 6–19, 2014 FEB 6–19, #764 CAN THIS PILL PREVENT @dailyxtra facebook.com/dailyxtra facebook.com/dailyxtra HIV? The promise and uncertainty of dailyxtra.com pre-exposure prophylaxis E14 More at More 2 FEB 6–19, 2014 XTRA! TORONTO’S GAY & LESBIAN NEWS COMING SOON AT YONGE WITH DIRECT ACCESS TO WELLESLEY SUBWAY A series of illuminated boxes, carefully stacked. Spaces shifted gently left and right, geometry that draws the eye skyward. Totem, a building that’s poised to be iconic, is about great design and a location that fits you to a T. When you live here, you can go anywhere. Yonge Street, Yorkville, the Village, College Park, Yonge- Dundas Square, the Annex, University of Toronto and Ryerson are just steps away. IN FACT, TOTEM SCORES A PERFECT 100 ON WALKSCORE.COM! Plus, you’ve got sleek, modern suites, beautiful rooftop amenities and DIRECT ACCESS TO YOUR OWN SUBWAY ENTRANCE. THIS IS TOTEM. FROM THE MID $200’S SHIFT YOUR LIFESTYLE. get on it. REGISTER. totemcondos.com 416.792.1877 17 dundonald st. @ yonge street RENDERINGS ARE AN ARTIST’S IMPRESSION. SPECIFICATIONS ARE SUBJECT TO CHANGE WITHOUT NOTICE. E.&O.E. EXCLUSIVE LISTING: BAKER REAL ESTATE INCORPORATED, BROKERAGE. BROKERS PROTECTED. MORE AT DAILYXTRA.COM XTRA! FEB 6–19, 2014 3 XTRA Published by Pink Triangle Press SHERBOURNE HEALTH CENTRE PUBLISHER & EDITOR-IN-CHIEF Brandon Matheson 333 SHERBOURNE STREET TORONTO, ON M5A 2S5 EDITORIAL ADVERTISING MANAGING EDITOR Danny Glenwright ADVERTISING & SALES DIRECTOR Ken Hickling -

Investigating Race, Space and Meaning in Toronto's Queer Party

AND YA DON’T STOP: INVESTIGATING RACE, SPACE AND MEANING IN TORONTO’S QUEER PARTY ‘YES YES Y’ALL’ by Trudie Jane Gilbert, BSW, University of British Columbia, 2015 A Major Research Paper presented to Ryerson University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in the program of Immigration and Settlement Studies Toronto, Ontario, Canada © Trudie Jane Gilbert 2017 AUTHOR’S DECLARATION I hereby declare that I am the sole author of this Major Research Paper. This is a true copy of the MRP, including any required final revisions. I authorize Ryerson University to lend this MRP to other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I further authorize Ryerson University to reproduce this MRP by photocopying or by other means, in total or in part, at the request of other institutions or individuals for the purpose of scholarly research. I understand that my MRP may be made electronically available to the public. Trudie Jane Gilbert ii AND YA DON’T STOP: INVESTIGATING RACE, SPACE AND MEANING IN TORONTO’S QUEER PARTY ‘YES YES Y’ALL’ Trudie Jane Gilbert Master of Arts 2017 Immigration and Settlement Studies Ryerson University ABSTRACT This Major Research Paper (MRP) is a case study of the queer hip hop and dancehall party Yes Yes Y’all (YYY). This MRP seeks to challenge white, cismale metanarratives in Toronto’s queer community. This paper employs Critical Race Theory (CRT) and queer theory as theoretical frameworks. Racialization, racism, homophobia, homonormativities and homonational rhetoric within queer discourses are interrogated throughout the analysis. -

UAAC Conference.Pdf

Friday Session 1 : Room uaac-aauc1 : KC 103 2017 Conference of the Universities Art Association of Canada Congrès 2017 de l’Association d’art des universités du Canada October 12–15 octobre, 2017 Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity uaac-aauc.com UAAC - AAUC Conference 2017 October 12-15, 2017 Banff Centre for Arts and Creativity 1 Welcome to the conference The experience of conference-going is one of being in the moment: for a few days, we forget the quotidian pressures that crowd our lives, giving ourselves over to the thrill of being with people who share our passions and vocations. And having Banff as the setting just heightens the delight: in the most astonishingly picturesque way possible, it makes the separation from everyday life both figurative and literal. Incredibly, the members of the Universities Art Association of Canada have been getting together like this for five decades—2017 is the fifteenth anniversary of the first UAAC conference, held at Queen’s University and organized around the theme of “The Arts and the University.” So it’s fitting that we should reflect on what’s happened in that time: to the arts, to universities, to our geographical, political and cultural contexts. Certainly David Garneau’s keynote presentation, “Indian Agents: Indigenous Artists as Non-State Actors,” will provide a crucial opportunity for that, but there will be other occasions as well and I hope you will find the experience productive and invigorating. I want to thank the organizers for their hard work in bringing this conference together. Thanks also to the programming committee for their great work with the difficult task of reviewing session proposals. -

The Vazaleen Posters Mark Clintberg

Sticky: The Vazaleen Posters Mark Clintberg Abstract Vazaleen was a monthly serial queer party in Toronto founded by artist and promoter Will Munro (1975–2010) in 2000. Munro commissioned Toronto-based artist Michael Comeau (1975–) to create many silkscreen poster advertisements for these parties. His designs include an array of typographic treatments, references to popular culture and queer icons, and vibrant colour schemes. This article discusses these posters in relationship to Michel Foucault’s theory of the heterotopia, Roland Barthes’s semiotic analysis of advertising, and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick’s writing on camp. Résumé Vazaleen était une fête périodique queer à Toronto, fondée en 2000 par artiste et promoteur Will Munro (1975–2010). Munro a commandé à l’artiste torontois Michael Comeau (1975–) la création de nombreuses affiches publicitaires sérigraphiées pour ces fêtes. Les designs de Comeau comportent une gamme de traitements typographiques, des références à la culture populaire et aux idoles queer, et des modèles de couleurs vibrants. Cet article expose les affiches de Comeau en relation avec le concept de l’hétérotopie élaboré par Michel Foucault, l’analyse sémiotique de la publicité de Roland Barthes, et les écrits sur la culture camp d’Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick. Vaseline is: a sticky petroleum product used for moisturizing; a potential lubricant for sexual encounter; and a Toronto-based serial queer dance party founded by Canadian artist Will Munro (1975– 2010) and contributed to by the city’s queer, gay, lesbian, bisexual, and -

Camoutopia: Dazzle, Dance, Disrupt by Mary Elizabeth Tremonte

Camoutopia: Dazzle, Dance, Disrupt by Mary Elizabeth Tremonte A thesis exhibition presented to OCAD University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts in Interdisciplinary Master’s in Art, Media and Design Flex Studio Gold at Artscape Youngplace, April 2-12, 2014 Toronto, Ontario, Canada, April 2014 Mary Elizabeth Tremonte 2014 This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommercial-Share Alike 2.5 Canada license. To see the license go to http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/ or write to Creative Commons, 171 Second Street, Suite 300, San Francisco, California 94105, USA. Copyright Notice This document is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Noncommerical- Share Alike 2.5 Canada License. http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-nc-sa/2.5/ca/ You are free to: Share — copy and redistribute the material in any medium or format Adapt — remix, transform, and build upon the material The licensor cannot revoke these freedoms as long as you follow the license terms. Under the following conditions: Attribution — You must give appropriate credit, provide a link to the license, and indicate if changes were made. You may do so in any reasonable manner, but not in any way that suggests the licensor endorses you or your use. Non-Commercial — You may not use the material for commercial purposes. ShareAlike — If you remix, transform, or build upon the material, you must distribute your contributions under the same license as the original. No additional restrictions — You may not apply legal terms or technological measures that legally restrict others from doing anything the license permits. -

The Cord Weeklythe Tie That Binds Since 1926 GETTING the GRAD(E) HOLIDAY SURVIVAL Looking to Apply to Grad School? Find How to Maintain Your Christmas

The Cord WeeklyThe tie that binds since 1926 GETTING THE GRAD(E) HOLIDAY SURVIVAL Looking to apply to grad school? Find How to maintain your Christmas out how in our feature ... PAGES 16-17 spirit next month ... PAGES 19-21 Volume 48 Issue 16 WEDNESDAY NOVEMBER 28,2007 www.cordweekly.com Hawk rock round two The second round of Last Band Standing results in the victory of uncreative Hedley imposters REBECCA VASLUIANU almost like Tool's, Phineas Gage's STAFF WRITER poor vocals and unkempt gui- tar-work made the group sound Another battle between bands left more like radio-rejects Three Days the audience feeling unimpressed, Grace. energized and then just confused. Yet the low of Phineas Gage's Taking place at Wilf's last Thurs- sloppy performance came during day, the second round of Tast Band their second song, when Matthias Standing proved to be an enjoyable and bassist Aaron Schwab attempt- night alternating between great in- ed a vocal harmony at which even genuity and a few lame attempts at the most tone-deaf listener would have cringed. Competing for the title of Tast Despite this harsh critique, Band Standing were Phineas Gage, Phineas Gage showed buds of po- Crown and Coke and Music Box. tential through their interesting Heading up the night, Kitchener intros and solos, which displayed natives Phineas Gage delivered a lot more instrumental depth than an entirely subpar performance the rest of their material and were of depressing alternative rock, free from interference from Matth- which left the audience thoroughly ias's second-rate vocal stylings. -

General Idea, Andy Fabo, Tim Jocelyn, Chromazone Collective

The Aesthetics of Collective Identity and Activism in Toronto’s Queer and HIV/AIDS Community By Peter M. Flannery A Thesis presented to The University of Guelph In partial fulfilment of requirements for the degree of Master of Arts in Art History and Visual Culture Guelph, Ontario, Canada © Peter M. Flannery, April, 2019 ABSTRACT THE AESTHETICS OF COLLECTIVE IDENTITY AND ACTIVISM IN TORONTO’S QUEER AND HIV/AIDS COMMUNITY Peter M. Flannery Advisor: University of Guelph, 2019 Prof. A. Boetzkes This thesis investigates the social and political impacts of art and visual culture produced in Toronto from the 1970s to the present day through changing dynamics of gay liberation, raids of gay bathhouses by the Metropolitan Toronto Police Force during “Operation Soap,” and the continuing HIV/AIDS crisis. Throughout these historic moments, visual culture was an incubator by which artists formulated the values, performative identities, and political actions that defined their activism. Beginning with a brief history of LGBTQ2S+ issues in Toronto, this thesis analyzes selected works by General Idea, Andy Fabo, Tim Jocelyn, ChromaZone Collective, Will Munro, and Kent Monkman. By performing their identities within the public sphere, these artists developed communities of support and, through intensely affective and political acts, catalyzed social change to advocate for equal rights as well as funding, medical care, and reduced stigma in the fight against HIV/AIDS. DEDICATION To the artists, activists, and community builders whose fierce and devoted work catalyzed social change and acceptance. They have led the way in the continued advocacy for LGBTQ2S+ issues and the fight against the HIV/AIDS crisis. -

Adult Depot Calgary Men's Chorus Need Help?

December 2004 Issue 14 FREE of charge AAdultdult DDepotepot RReflectingeflecting bbackack oonn 2255 yyearsears CCalgaryalgary MMen’sen’s ChorusChorus UUnitingniting voicesvoices fforor 1100 yyearsears NNeedeed HHelp?elp? MMap,ap, PPlaceslaces aandnd EEventsvents ooff CCalgary’salgary’s GGayay CCommunityommunity iinn eeveryvery iissuessue CCalgary’salgary’s resourceresource fforor BBusiness,usiness, Tourism,Tourism, EEvents,vents, BBarsars aandnd EEntertainmentntertainment fforor tthehe GGay,ay, LLesbian,esbian, BBii aandnd GGayay FFriendlyriendly CCommunity.ommunity. http://www.gaycalgary.com 2 gaycalgary.com magazine 8 Established originally in January 1992 as Men For Men BBS by MFM Communications. Named changed to GayCalgary.com in 1998. Stand alone company as of January 2004. First Issue of GayCalgary.com Magazine, November 12 2003. Publisher Steve Polyak & Rob Diaz Marino Editor Rob Diaz Marino Table of Contents Original Graphic Design Deviant Designs 4 Taboos and Thank-Yous Advertising Steve Polyak [email protected] Letter from the Publisher Contributors 5 Just ask Nina Steve Polyak, Rob Diaz Marino, Nina Tron, Stephen Lock, M. Zelda, Jason Clevett and The Dish who dishes advice the Gay and Lesbian Community of Calgary 6 The Heterosexualizing of Photographer 16 Steve Polyak and Rob Diaz Marino History Videographer Steve Polyak and Rob Diaz Marino 8 Calgary Men’s Chorus Please forward all inquiries to: Uniting voices for 10 years. GayCalgary.com Magazine Suite 403, 215 14th Avenue S.W. Calgary, Alberta T2R 0M2 12 Adult Depot Phone (403) 543-6960 or toll free (888) Reflecting back on 25 years 543-6960 Fax (403) 703-0685 16 Map & Event Listings E-mail [email protected] Mapping Calgary’s core Print Run Monthly, 12 times a year 23 Queer Eye - for the Calgary guy (or gal) 23 Copies Printed Monthly, up to 10,000 copies. -

Annual Report 2014–2015 Art Gallery of York University

Annual Report 2014–2015 Art Gallery of York University “Amazing exhibition—wonderful resource for my class (MGD Studio). How lucky we are to have this right at York!” — York Professor “Such a welcome respite to enjoy the art in the middle of a busy day. Thank you for sharing it.” — York staff member “J’ai trouvé vos tableaux très beaux. Je reviendrai probablement une prochaine fois, avec plaisir !” “THAT WAS INCREDIBLE.” “So hip, very interesting and fun!” In conjunction with the Parapan Am Games, the AGYU commissioned and organized Ring of Fire, a 300-person procession from Queen’s Park to Nathan Phillip’s Square. The AGYU won an unprecedented seven Ontario Association of Art Galleries Awards. The AGYU was a finalist for Premier’s Awards for Excellence in the Arts. Creative Campaigning, with Los Angeles artist Heather Cassils, engaged students from Fundamentals of Social Work and the Department of Visual Art and Art History Printmaking in a multivalent, multi-part program that culminated in a participatory performance by fifty students viewed by hundreds on the Ross podium. The AGYU partnered with the School of the Arts, Media, Performance, and Design in the Louis Odette Sculptor-in-Residence program. The AGYU’s outreach extended throughout the whole GTA from Jane-Finch to include Malvern and Regent Park and downtown, with public presentations, 200 workshops with community arts organizations such as Malvern S.P.O.T., Art Starts, and Sketch. • 24 Canadian artists exhibited, with 110 works created specifically for the AGYU • 40 Community Art Projects, with over 800 participants and 1,850 attendees • Over 2,600 public participants in artist-in-residence projects Exhibitions Is Toronto Burning? : 1977|1978|1979: Three Years in the Making (and Unmaking) of the Toronto Art Scene The late 1970s was a key period when the To- ronto art scene was in formation and destruc- 17 September – 7 December 2014 tion—downtown, that is. -

Cruising "Alexander: the Other Side of Dawn" "Can We Talk" 31 Mins. By

CANADIAN LESBIAN AND GAY ARCHIVES Moving Images Cruising •"Different from the others", starring Conrad Veidt Theme(s): Homophobia (German, 1919) Credits: Jerry Weintraub. USA 1980 video/VHS •)"Respect", music video by Erasure (1989) Accession: 2007-119 Theme(s): •Film •Music England video/Beta Accession: "Alexander: The other Side of Dawn" Theme(s): Gay Youth "Family Secrets" Eps#1 "Birth Mothers Never Forget" USA 1977 video/VHS Theme(s): Families Remarks: Taped from Television. TV-movie sequel to Credits: Makin' Movies Inc. Canada 2003 video/VHS•22:45 "Dawn: Portrait of a Teenage Runaway" with Accession: 2006-008 Leigh J. McCloskeyas a youth trying to escape the sordid world of male prostitution. Eve Plumb, Earl Holliman, Alan Feinstein, Juliet Mills. "I Believe in the Good of Life" West Wing footage. Accession: 2006-155 Dec. 2001. From West Wing Art Space. Many Art Fags including the debut of The Hidden Cameras. "Can We Talk" 31 mins. By Norman Taylor for the Theme(s): •Art Coalition for Lesbian/ Gay Rights in Ontario. •Parties Credits: Norman Taylor. video/VHS•30:55 Credits: Shot by Guntar Kravis. Canada Dec. 2001 video/VHS Remarks: Item is a slideshow video which discusses and Accession: 2006-053 debunks myths in the gay and lesbian community. Myths include the following: "Gay "Is He. ." can be spotted a mile away", "Homosexuals Theme(s): •Coming Out are known by the type of work they do", •Comedy "Homosexual is a sickness", "Homosexuals are Credits: Director: Linda Carter•Writer: Charlie David•Actor: Charlie child molesters", :Homosexuality is David. Canada 2004 other (see Form Details field)•Mini DV•9 min.