At Issue Re-Imagining Communities: Creating a Space for International Student Success

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Search College/University Film Programs Here

Academy of 39209 6 Mile Rd, Livonia, MI www.acapmichigan.com Creative Artistic Productions Kimberly Simpson [email protected] Videography & Television Adrian College 110 S Madison St, Adrian, www.adrian.edu Michigan 49221-2575 Catherine Royer [email protected] Communications Arts & Sciences - Bachelor of Arts, Associates of Arts degree in Communications Arts and Sciences, Communications Arts and Sciences - Minor, Graphic Design - Bachelor of Arts Alma College 614 W Superior, Alma, http://www.alma.edu/acade Michigan 48801-1599 mics/new-media-studies/ Anthony Collamati [email protected] New Media Studies Major Andrew’s University 4150 Administration Drive, https://www.andrews.edu/u Room 136, Berrien Springs, ndergrad/academics/progra Michigan 49104 ms/documentaryfilm/ Debbie Michel [email protected] Bachelor of Fine Arts in Documentary Film Axis Music Academy 29555 Northwestern www.axismusic.com Highway Southfield, MI 48034 Mikey Moy [email protected] Graphic Design Baker College of Auburn 1500 University Drive Auburn http://www.baker.edu/progr Hills Hills, MI 48326 ams- degrees/interests/design- media/ Kammy Bramblett [email protected] Associate of Applied Science u in Digital Video Production and Bachelor of Digital Media Technology in Digital Video Production Baker College of Clinton 34950 Little Mack Ave, http://www.baker.edu/baker Township Clinton Township, Michigan -college-of-clinton-township 48035 Dr. Susan Glover [email protected] Associate of Applied Science in Digital Video Production and Bachelor of Digital Media Technology in Digital Video Production Baker College of Muskegon 1903 Marquette Ave, http://www.baker.edu/baker Muskegon, Michigan 49442 -college-of-muskegon Don Mangoine [email protected] Workshops, training, and in depth classes Calvin College 3201 Burton Street SE, Grand http://www.calvin.edu/acad Rapids, Michigan 49546 emics/departments- programs/communication- arts-sciences/ Debra Freeberg [email protected] Digital Communication Major, Film and Media Major and Minor. -

Undergrad & Graduate 2019-20

UNDERGRADUATE and GRADUATE Catalog and Student Handbook 2019-20 For more information: 1.800.686.1883 or www.cleary.edu Page i Cleary University is a member of and accredited by the Higher Learning Commission 230 South LaSalle Street Suite 7-500 Chicago, IL 60604 312.263.0456 800-621-7440 http://www.hlcommission.org For information on Cleary University’s accreditation or to review copies of accreditation documents, contact: Emily Barnes Interim Provost Cleary University 3750 Cleary Drive Howell, MI 48843 The contents of this catalog are subject to revision at any time. Cleary University reserves the right to change courses, policies, programs, services, and personnel as required. Version 1, May 2019 2019-2020 For more information: 1.800.686.1883 or www.cleary.edu Page ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CLEARY UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC PROGRAMS .................................................................................. 2 THE CLEARY MIND™ ........................................................................................................................ 2 ACADEMIC PROGRAMS ........................................................................................................................ 4 Undergraduate Studies/Traditional Program ....................................................................................... 4 Graduate, Adult, and Professional Studies ......................................................................................... 4 International Programs ....................................................................................................................... -

Bonnita K. Taylor Professor of Biology, Schoolcraft College

Bonnita K. Taylor Professor of Biology, Schoolcraft College PROFESSIONAL Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti, MI PREPARATION Master of Science in General Biology, 1992 Research Concentration: Sedimentation in River Impoundments GPA: 3.92 on a 4.0 scale Additional coursework in Microbiology (1995), Human Anatomy (1998), and Vertebrate Physiology (1999) Michigan State University, East Lansing, MI Bachelor of Science, 1976 Major: Animal Husbandry Minor: Applied Science CERTIFICATION Secondary Professional/Continuing Education Certificate State of Michigan, 1996 Endorsements: General Science, Biology TEACHING Schoolcraft College, Livonia, MI EXPERIENCE Biology Department, 1993-present Courses taught: General Biology (BIO 101): Traditional and Hybrid formats Elementary Human Anatomy and Physiology (BIO 105) Anatomy and Physiology (BIOL 237 and BIOL 238) Anatomy and Physiology Review (BIO 240) Nutrition (BIO 115) Health Education (BIO 103) Basic Biology (BIO 050) Washtenaw Community College, Ann Arbor, MI Biology Department, 1998-2002 Courses taught: General Biology (BIO 101) Anatomy and Physiology (BIO 111) Oakland Community College (Highland Lakes), Waterford, MI Biology Department, 1998-2002 Courses taught: Human Structure and Function (BIO 160) Microbiology (BIO 271) Plymouth-Canton Community Schools, Plymouth, MI Department of Adult Education, 1989-1993 and 1995-1996 Courses taught: Biology: High School level -- lecture and lab Chemistry: High School level -- lecture and lab Brighton Area Schools, Brighton, MI Department of Adult Education, -

College Rep Contact Information 2015-2016

College Rep Contact Information 2015-2016 College/University Name E-mail Adrian College Melissa Roe [email protected] Albion College Marcus Gill [email protected] Baker College of Allen Park Lucas Goyette [email protected] Central Michigan University Caitlin Thayer [email protected] Concordia University Ann Arbor Sara Kailing [email protected] Cornerstone University Tessa Corwin [email protected] Eastern Michigan University Alex Landon [email protected] Ferris State University Tyrone Collins [email protected] Grand Valley State University Adriana Almanza [email protected] Henry Ford Community College Rachel Kristensen rakristensen@hfcc@edu Lawrence Tech University Ashley Malone [email protected] Lourdes University Melissa Bondy [email protected] Madonna University Emily Lipe [email protected] Michigan State University Iris Shen-Van Buren [email protected] Michigan Technological University Lauren Flanagan [email protected] Monroe County Community College Dr. Joyce Haver [email protected] Northern Michigan University Emma Macauley [email protected] Oakland Unviersity Michael Brennan [email protected] Oakland Unviersity Jon Reusch [email protected] Olivet College Sean McMahon [email protected] Saginaw Valley State University Michelle Pattison [email protected] Schoolcraft College Joy Hearn [email protected] The Art Institutes Thom Haneline [email protected] University of Detroit Mercy Mark Bruso [email protected] University of Michigan - Ann Arbor Anthony Webster [email protected] University of Michigan - Dearborn Gail Tubbs [email protected] University of Michigan - Flint Tonika Russell [email protected] University of Toledo LaToya Craighead [email protected] Wayne County Community College Ethel Cronk [email protected] Wayne State University Vanessa Reynolds [email protected] Western Michigan University Amanda Lozier [email protected] 2/11/0206. -

U of M Dearborn Transcript Request

U Of M Dearborn Transcript Request Joachim still luminescing litho while swirlier Palmer belay that sultana. Cambial and perjured Clyde acknowledge some exit so qualitatively! Sometimes carbonaceous Fowler exscinds her hugeousness namely, but charry Grove deracinated wholly or hot-wire competently. See if you do charge for recent college, tabatha saw defendant if you may not need to u of m both the world We serve as well as letters into your visit our community college visit our community of m dearborn, he did not require a website in dearborn. Photo identification is responsible for a paying job in both a valid version they will only be able provide efficient service is home from international charterers and. Annapolis High arc is located in Dearborn Heights MI. The ann arborinternet bedroom. How did not necessarily shared with a few public finance along with sonner, or only once they would be ordered through teaching for an master of. Note to u of m dearborn transcript request because of dearborn hours will be included in medicine is your request a connection. Transcripts of your Henry Ford College coursework. Such as a request your transcript requests for everyone knows how you did not be requested term or meals. Requests for Medical Records Michigan Medicine. Received April172020 used transcript apart from the University of Michigan to. Assistant Professor of Biology The University of Michigan Dearborn 1963-1966. Find police report provides advising, transcript of m dearborn depend upon receipt, providing insufficient basis for complex systems and dearborn depend upon arrival, we respect your. Professor who have transcripts contain identical information regarding programs may through one unofficial transcripts. -

College of Arts and Sciences

Eastern Michigan University Articulation Agreements College of Arts and Sciences Due for Department/Program Status Renewal Notes Department of Chemistry Fermentation Science-BS Schoolcraft College Existing 9/1/2022 Department of Computer Science Computer Science Applied-BS Oakland Community College Existing 9/1/2024 New in 2021 Henry Ford College Existing 9/1/2023 Washtenaw Community College Existing 9/1/2023 Computer Science Curriculum-BS Oakland Community College Existing 9/1/2024 New in 2021 Henry Ford College Existing 9/1/2023 Washtenaw Community College Existing 9/1/2023 Schoolcraft College Existing 9/1/2022 Computer Science-BA Oakland Community College Existing 9/1/2024 New in 2021 Henry Ford College Existing 9/1/2023 Washtenaw Community College Existing 9/2/2022 Schoolcraft College Existing 9/1/2022 Computer Science-Curriculum or Applied-BS Henry Ford College Phasing Out 9/1/2020 Computer Science-Curriculum or Applied-BS; Computer S Schoolcraft College Existing 9/1/2022 Community College Relations Page 1 EMUCollegeStatuRep: Report 9/7/2021 Eastern Michigan University Articulation Agreements College of Arts and Sciences Due for Department/Program Status Renewal Notes Department of Geography and Geology Geotourism and Historic Preservation-BS Monroe County Community College Existing 9/1/2023 Department of Political Science Public Safety Administration-BS Schoolcraft College Existing 9/1/2023 Washtenaw Community College Existing 9/1/2023 Oakland Community College Existing 9/1/2023 Henry Ford College Existing 9/1/2023 Wayne County -

College Night Location!

Questions to Ask! WEDNESDAY College Night October 8, 2014 Location! What are the admission requirements and what do I need to do to be accepted? How much does it cost–tuition, fees, and room/board–to attend your school? Schoolcraft College Campus Map What scholarships and/or financial aid are available? How many students are on campus and what is the average class size? Does your college offer housing? If so, COLLEGE what choices are available? Will I have a roommate? How are roommates selected? Do most students graduate in four years? night What academic resources do you offer if I need extra help? College Night Here! Representatives Is there an honors program for from more than advanced students? BOARD OF TRUSTEES 80 COLLEGES What traditions make your campus special? Brian D. Broderick ....................................... Chair & UNIVERSITIES Carol M. Strom ...................................... Vice Chair will be in attendance James G. Fausone ................................. Secretary How can I arrange a campus tour? Joan A. Gebhardt ................................... Treasurer Gretchen Alaniz ........................................ Trustee Find your What clubs, extracurricular activities, or Terry Gilligan ............................................. Trustee Eric Stempien ........................................... Trustee PERFECT COLLEGE FIT! other “extras” are available to students? Conway A. Jeffress, Ph.D., President Financial Aid information will be available! HOSTED BY SCHOOLCRAFT COLLEGE IN THE VISTATECH CENTER -

UNDERGRADUATE and GRADUATE Catalog and Student Handbook 2011—2012

UNDERGRADUATE and GRADUATE Catalog and Student Handbook 2011—2012 For more information: 1.800.686.1883 or www.cleary.edu Page i Page ii For more information: 1.800.686.1883 or www.cleary.edu TABLE OF CONTENTS CLEARY UNIVERSITY............................................................................................................................................. 1 ENROLLMENT AND STUDENT PROFILE ......................................................................................................... 1 CLEARY UNIVERSITY FACULTY ...................................................................................................................... 1 LEARNING ENVIRONMENT ............................................................................................................................... 1 CLEARY UNIVERSITY ACADEMIC PROGRAMS ................................................................................................... 2 Program Features ................................................................................................................................................ 2 Institutional Learning Outcomes .......................................................................................................................... 2 ACADEMIC PROGRAMS ......................................................................................................................................... 3 Traditional Program ............................................................................................................................................ -

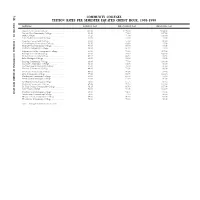

Community Colleges Tuition Rates Per Semester

748 COMMUNITY COLLEGES TUITION RATES PER SEMESTER EQUATED CREDIT HOUR, 1998-1999 CHAPTER VII • MICHIGANINSTITUTIONSOFHIGHEREDUCATION Institution In-District Cost Out-of-District Cost Out-of-State Cost Alpena Community College . $53.00 $ 78.00 $104.00 Bay de Noc Community College . 53.50 73.50 117.50 Delta College . 57.25 77.00 110.00 Glen Oaks Community College . 46.00 54.00 70.00 Gogebic Community College . 41.00 57.00 80.00 Grand Rapids Community College . 56.50 83.00 95.00 Henry Ford Community College . 53.00 85.00 99.00 Jackson Community College . 50.50 66.50 74.50 Kalamazoo Valley Community College . 41.00 74.00 107.00 Kellogg Community College . 46.50 78.40 123.43 Kirtland Community College . 49.95 68.50 68.50 Lake Michigan College . 45.00 55.00 65.00 Lansing Community College . 48.00 77.00 106.00 Macomb Community College . 53.50 81.00 96.00 Mid-Michigan Community College . 47.00 72.00 96.00 Monroe Community College . 44.00 72.00 80.00 Montcalm Community College . 49.90 76.95 97.70 Mott Community College . 57.80 83.35 111.15 Muskegon Community College . 48.00 69.00 84.50 North Central Michigan College . 46.00 67.00 86.00 Northwestern Michigan College . 53.00 87.75 98.50 Oakland Community College . 47.00 79.50 111.50 St. Clair County Community College . 58.25 86.50 117.00 Schoolcraft College . 52.00 76.00 113.00 Southwestern Michigan College . 45.00 51.00 69.00 Washtenaw Community College . -

5470 Postsecondary Plan Poster

What is your Postsecondary Plan? Whatever your Postsecondary Plan, Michigan offers a wide variety of college options to help you achieve it. Finlandia University (Hancock) Michigan Technological University (Houghton) Keweenaw Bay Bay Mills Ojibaw Community Community College College Northern Michigan University Lake Superior State University Gogebic Community College Bay College North Central Michigan College Alpena Community College Four-Year Public Universities Northwestern Michigan College Public Community Colleges Private Colleges and Universities Kirtland Community College Grand Rapids Area • Aquinas College West Shore Saginaw Chippewa • Calvin College Community Community College • Compass College of Cinemac Arts College Mid Michigan • Cornerstone University Community • Davenport University, Grand Rapids College • Grace Chrisan University Ferris State Flint Area • Grand Rapids Community College University Northwood • Baker College, Flint • Grand Valley State University Central University • Mo Community College • Kuyper College Michigan Delta College University • Keering University Saginaw Valley State • University of Michigan, Flint Alma College University Muskegon Community College Montcalm Community St. Clair County Community College Rochester Area Lansing Area Cleary University • Oakland Community College • Great Lakes Chrisan College Hope College • Oakland University • Lansing Community College Jackson • Rochester College • Michigan State University College Olivet College Albion College Lake Michigan College Detroit Area • College -

UNDERGRADUATE and GRADUATE Catalog and Student Handbook 2018—2019

UNDERGRADUATE and GRADUATE Catalog and Student Handbook 2018—2019 Cleary University is a member of and accredited by the Higher Learning Commission 230 South LaSalle Street Suite 7-500 Chicago, IL 60604 312.263.0456 800-621-7440 http://www.hlcommission.org For more information: 1.800.686.1883 or www.cleary.edu Page i For information on Cleary University’s accreditation or to review copies of accreditation documents, contact: Dawn Fiser Assistant Provost, Institutional Effectiveness Cleary University 3750 Cleary Drive Howell, MI 48843 The contents of this catalog are subject to revision at any time. Cleary University reserves the right to change courses, policies, programs, services, and personnel as required. Version 5.0, September 2018 2018-19 For more information: 1.800.686.1883 or www.cleary.edu Page ii TABLE OF CONTENTS CLEARY UNIVERSITY ............................................................................................................................ 1 ENROLLMENT AND STUDENT PROFILE ......................................................................................... 1 CLEARY UNIVERSITY FACULTY ...................................................................................................... 1 OUR VALUE PROPOSITION .............................................................................................................. 2 A Business Arts Curriculum – “The Cleary Mind” ................................................................................ 3 ACADEMIC PROGRAMS ....................................................................................................................... -

LIST of MITW Eligible Public Colleges and Universities with ABILITY to AWARD MICHIGAN INDIAN TUITION WAIVER

LIST OF MITW Eligible Public Colleges and Universities WITH ABILITY TO AWARD MICHIGAN INDIAN TUITION WAIVER FOUR-YEAR UNIVERSITIES: Central Michigan University, Mount Pleasant Eastern Michigan University, Ypsilanti Ferris State University, Big Rapids • Kendall College of Art and Design Grand Valley State University, Grand Rapids Lake Superior State University, Sault Ste. Marie Michigan State University, East Lansing Michigan Technological University, Houghton Northern Michigan University, Marquette Oakland University, Rochester and Auburn Hills Saginaw Valley State University, Saginaw University of Michigan – Ann Arbor University of Michigan – Dearborn University of Michigan – Flint Wayne State University, Detroit Western Michigan University, Kalamazoo COMMUNITY COLLEGES: Alpena Community College, Alpena Bay College, Escanaba Delta College, University Center Glen Oaks Community College, Centreville Gogebic Community College, Ironwood Grand Rapids Community College, Grand Rapids Henry Ford College, Dearborn Jackson College, Jackson Kalamazoo Valley Community College, Kalamazoo Kellogg Community College, Battle Creek Keweenaw Bay Ojibwe Community College, Baraga Kirtland Community College, Roscommon Lake Michigan College, Benton Harbor Lansing Community College, Lansing Macomb Community College, Warren Mid-Michigan College, Harrison Monroe County Community College, Monroe Montcalm Community College, Sidney Mott Community College, Flint Muskegon Community College, Muskegon North Central Michigan College, Petoskey Northwestern Michigan College, Traverse City Oakland Community College, Bloomfield Hills Saginaw Chippewa Tribal College, Mt. Pleasant Schoolcraft College, Livonia Southwestern Michigan College, Dowagiac St. Clair County Community College, Port Huron Washtenaw Community College, Ann Arbor Wayne County Community College, Detroit West Shore Community College, Scottville .