Environmental Predictors of Habitat Suitability and Occurrence Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Identifying Sexually Mature, Male Short-Beaked Common Dolphins (Delphinus Delphis) at Sea, Based on the Presence of a Postanal Hump

Aquatic Mammals 2002, 28.2, 181–187 Identifying sexually mature, male short-beaked common dolphins (Delphinus delphis) at sea, based on the presence of a postanal hump Dirk R. Neumann1, Kirsty Russell2, Mark B. Orams1, C. Scott Baker2, and Padraig Duignan3 1Coastal Marine Research Group, Massey University, Auckland, New Zealand 2Department of Biology, University of Auckland, New Zealand 3Department of Veterinary Science, Massey University, Palmerston North, New Zealand Abstract Introduction For detailed studies on the behaviour and social To fully comprehend the behaviour and social organization of a species, it is important to organization of a species, it is necessary to distinguish males and females. Many delphinid distinguish males and females. Long-term studies species show little sexual dimorphism. However, in of bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus, T. mature male spinner dolphins, Stenella longirostris aduncus), which tracked focal individuals of known (Perrin & Gilpatrick, 1994) and Fraser’s dolphins, sex, revealed sexual segregation of mature males Lagenodelphis hosei (Jefferson et al., 1997), tissue from females (Wells, 1991), the formation of male between the anus and the flukes forms a so-called coalitions (Wells, 1991; Connor et al., 1992), and peduncle keel, or postanal hump. We discovered an differences in the activity budgets of males and analogous feature in free-ranging short-beaked females (Waples et al., 1998). Many delphinid common dolphins, Delphinus delphis,offthe species show little sexual dimorphism, which makes north-eastern coast of New Zealand’s North Island. it exceedingly difficult to sex individuals at sea. For Genetic analysis of skin samples obtained from many species, the only individuals that can be sexed bow-riding individuals revealed that dolphins without capture are those that are consistently with a postanal hump were indeed always male. -

Anomalously Pigmented Common Dolphins (Delphinus Sp.) Off Northern New Zealand Karen A

Aquatic Mammals 2005, 31(1), 43-51, DOI 10.1578/AM.31.1.2005.43 Anomalously Pigmented Common Dolphins (Delphinus sp.) off Northern New Zealand Karen A. Stockin1 and Ingrid N. Visser2 1Coastal-Marine Research Group, Institute of Natural Resources, Massey University, Private Bag 102 904, North Shore MSC, Auckland, New Zealand 2Orca Research Trust, P.O. Box 1233, Whangarei, New Zealand Abstract New Zealand waters is provided by Bernal et al. (2003) who suggested that common dolphins exhib- Anomalous pigmentations have been recorded in iting long rostra, as photographed in New Zealand many cetacean species. However, typically only by Doak (1989; Plates 34A, 34B), are long-beaked one variation is reported from a population at common dolphins. However, as Amaha (1994) and a time (e.g., an albino). Here we record a spec- Jefferson & Van Waerebeek (2002) highlighted, trum of pigmentation from common dolphins neither New Zealand nor Australian common dol- (Delphinus sp.) off northern New Zealand. All- phins neatly fit the morphological description of black, dark-morph, pale-morph, and all-white either D. delphis or D. capensis. In the past, New individuals, as well as variations between these Zealand common dolphins have been identified have been recorded. Pale-coloured pectoral flip- from pigmentation patterns in the field and classi- pers are prevalent, and a number of individuals fied as short-beaked common dolphins (Bräger & with white “helmets” have been observed. Schneider, 1998; Gaskin, 1968; Neumann, 2001; Webb, 1973), although pigmentation alone may not Key Words: common dolphin, Delphinus delphis, be sufficient to positively identity these dolphins to Delphinus capensis, anomalous pigmentation, species. -

List of Marine Mammal Species and Subspecies Written by The

List of Marine Mammal Species and Subspecies Written by the Committee on Taxonomy The Ad-Hoc Committee on Taxonomy , chaired by Bill Perrin, has produced the first official SMM list of marine mammal species and subspecies. Consensus on some issues was not possible; this is reflected in the footnotes. This list will be revisited and possibly revised every few months reflecting the continuing flux in marine mammal taxonomy. This list can be cited as follows: “Committee on Taxonomy. 2009. List of marine mammal species and subspecies. Society for Marine Mammalogy, www.marinemammalscience.org, consulted on [date].” This list includes living and recently extinct species and subspecies. It is meant to reflect prevailing usage and recent revisions published in the peer-reviewed literature. Author(s) and year of description of the species follow the Latin species name; when these are enclosed in parentheses, the species was originally described in a different genus. Classification and scientific names follow Rice (1998), with adjustments reflecting more recent literature. Common names are arbitrary and change with time and place; one or two currently frequently used in English and/or a range language are given here. Additional English common names and common names in French, Spanish, Russian and other languages are available at www.marinespecies.org/cetacea/ . The cetaceans genetically and morphologically fall firmly within the artiodactyl clade (Geisler and Uhen, 2005), and therefore we include them in the order Cetartiodactyla, with Cetacea, Mysticeti and Odontoceti as unranked taxa (recognizing that the classification within Cetartiodactyla remains partially unresolved -- e.g., see Spaulding et al ., 2009) 1. -

213 Subpart I—Taking and Importing Marine Mammals

National Marine Fisheries Service/NOAA, Commerce Pt. 218 regulations or that result in no more PART 218—REGULATIONS GOV- than a minor change in the total esti- ERNING THE TAKING AND IM- mated number of takes (or distribution PORTING OF MARINE MAM- by species or years), NMFS may pub- lish a notice of proposed LOA in the MALS FEDERAL REGISTER, including the asso- ciated analysis of the change, and so- Subparts A–B [Reserved] licit public comment before issuing the Subpart C—Taking Marine Mammals Inci- LOA. dental to U.S. Navy Marine Structure (c) A LOA issued under § 216.106 of Maintenance and Pile Replacement in this chapter and § 217.256 for the activ- Washington ity identified in § 217.250 may be modi- fied by NMFS under the following cir- 218.20 Specified activity and specified geo- cumstances: graphical region. (1) Adaptive Management—NMFS 218.21 Effective dates. may modify (including augment) the 218.22 Permissible methods of taking. existing mitigation, monitoring, or re- 218.23 Prohibitions. porting measures (after consulting 218.24 Mitigation requirements. with Navy regarding the practicability 218.25 Requirements for monitoring and re- porting. of the modifications) if doing so cre- 218.26 Letters of Authorization. ates a reasonable likelihood of more ef- 218.27 Renewals and modifications of Let- fectively accomplishing the goals of ters of Authorization. the mitigation and monitoring set 218.28–218.29 [Reserved] forth in the preamble for these regula- tions. Subpart D—Taking Marine Mammals Inci- (i) Possible sources of data that could dental to U.S. Navy Construction Ac- contribute to the decision to modify tivities at Naval Weapons Station Seal the mitigation, monitoring, or report- Beach, California ing measures in a LOA: (A) Results from Navy’s monitoring 218.30 Specified activity and specified geo- graphical region. -

Cetaceans: Whales and Dolphins

CETACEANS: WHALES AND DOLPHINS By Anna Plattner Objective Students will explore the natural history of whales and dolphins around the world. Content will be focused on how whales and dolphins are adapted to the marine environment, the differences between toothed and baleen whales, and how whales and dolphins communicate and find food. Characteristics of specific species of whales will be presented throughout the guide. What is a cetacean? A cetacean is any marine mammal in the order Cetaceae. These animals live their entire lives in water and include whales, dolphins, and porpoises. There are 81 known species of whales, dolphins, and porpoises. The two suborders of cetaceans are mysticetes (baleen whales) and odontocetes (toothed whales). Cetaceans are mammals, thus they are warm blooded, give live birth, have hair when they are born (most lose their hair soon after), and nurse their young. How are cetaceans adapted to the marine environment? Cetaceans have developed many traits that allow them to thrive in the marine environment. They have streamlined bodies that glide easily through the water and help them conserve energy while they swim. Cetaceans breathe through a blowhole, located on the top of their head. This allows them to float at the surface of the water and easily exhale and inhale. Cetaceans also have a thick layer of fat tissue called blubber that insulates their internals organs and muscles. The limbs of cetaceans have also been modified for swimming. A cetacean has a powerful tailfin called a fluke and forelimbs called flippers that help them steer through the water. Most cetaceans also have a dorsal fin that helps them stabilize while swimming. -

Lagenodelphis Hosei – Fraser's Dolphin

Lagenodelphis hosei – Fraser’s Dolphin Assessment Rationale The species is suspected to be widespread and abundant and there have been no reported population declines or major threats identified that could cause a range-wide decline. Globally, it has been listed as Least Concern and, within the assessment region, it is not a conservation priority and therefore, the regional change from Data Deficient to Least Concern reflects the lack of major threats to the species. The most prominent threat to this species globally may be incidental capture in fishing gear and, although this is not considered a major threat to this species in the assessment region, Fraser’s Dolphins have become entangled in anti-shark nets off South Africa’s east coast. This threat should be monitored. Regional Red List status (2016) Least Concern Regional population effects: Fraser’s Dolphin has a widespread, pantropical distribution, and although its National Red List status (2004) Data Deficient seasonal migration patterns in southern Africa remain Reasons for change Non-genuine change: inconclusive, no barriers to dispersal have been New information recognised, thus rescue effects are possible. Global Red List status (2012) Least Concern TOPS listing (NEMBA) (2007) None Distribution The distribution of L. hosei is suggested to be pantropical CITES listing (2003) Appendix II (Robison & Craddock 1983), and is widespread across the Endemic No Pacific and Atlantic Oceans (Ross 1984), and the species has been documented in the Indian Ocean off South This species is occasionally Africa’s east coast (Perrin et al. 1973), in Sri Lanka misidentified as the Striped Dolphin (Stenella (Leatherwood & Reeves 1989), Madagascar (Perrin et al. -

Diet of the Striped Dolphin, Stenella Coeruleoalba, in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Publications, Agencies and Staff of the U.S. Department of Commerce U.S. Department of Commerce 3-2008 Diet of the Striped Dolphin, Stenella coeruleoalba, in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean William F. Perrin Kelly M. Robertson William A. Walker Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdeptcommercepub Part of the Environmental Sciences Commons Perrin, William F.; Robertson, Kelly M.; and Walker, William A., "Diet of the Striped Dolphin, Stenella coeruleoalba, in the Eastern Tropical Pacific Ocean" (2008). Publications, Agencies and Staff of the U.S. Department of Commerce. 23. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/usdeptcommercepub/23 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the U.S. Department of Commerce at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications, Agencies and Staff of the U.S. Department of Commerce by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. NOAA Technical Memorandum NMFS T O F C E N O M M T M R E A R P C E E D MARCH 2008 U N A I C T I E R D E M ST A AT E S OF DIET OF THE STRIPED DOLPHIN, Stenella coeruleoalba, IN THE EASTERN TROPICAL PACIFIC OCEAN William F. Perrin Kelly M. Robertson William A. Walker NOAA-TM-NMFS-SWFSC-418 U.S. DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration National Marine Fisheries Service Southwest Fisheries Science Center The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), organized in 1970, has evolved into an agency which establishes national policies and manages and conserves our oceanic, coastal, and atmospheric resources. -

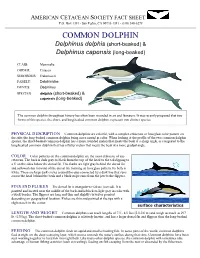

COMMON DOLPHIN Delphinus Delphis (Short-Beaked) & Delphinus Capensis (Long-Beaked)

AMERICAN CETACEAN SOCIETY FACT SHEET P.O. Box 1391 - San Pedro, CA 90733-1391 - (310) 548-6279 COMMON DOLPHIN Delphinus delphis (short-beaked) & Delphinus capensis (long-beaked) CLASS: Mammalia ORDER: Cetacea SUBORDER: Odontoceti FAMILY: Delphinidae GENUS: Delphinus SPECIES: delphis (short-beaked) & capensis (long-beaked) The common dolphin throughout history has often been recorded in art and literature. It was recently proposed that two forms of this species, the short- and long-beaked common dolphin, represent two distinct species. PHYSICAL DESCRIPTION Common dolphins are colorful, with a complex crisscross or hourglass color pattern on the side; the long-beaked common dolphin being more muted in color. When looking at the profile of the two common dolphin species, the short-beaked common dolphin has a more rounded melon that meets the beak at a sharp angle, as compared to the long-beaked common dolphin that has a flatter melon that meets the beak at a more gradual angle. COLOR Color patterns on the common dolphin are the most elaborate of any cetacean. The back is dark gray-to-black from the top of the head to the tail dipping to a V on the sides below the dorsal fin. The flanks are light gray behind the dorsal fin and yellowish-tan forward of the dorsal fin, forming an hourglass pattern. Its belly is white. There are large dark circles around the eyes connected by a dark line that runs across the head behind the beak and a black stripe runs from the jaw to the flippers. FINS AND FLUKES The dorsal fin is triangular-to-falcate (curved). -

Bottlenose Dolphin Abundance in the NW Mediterranean: Addressing Heterogeneity in Distribution

MARINE ECOLOGY PROGRESS SERIES Vol. 275: 275–287, 2004 Published July 14 Mar Ecol Prog Ser Bottlenose dolphin abundance in the NW Mediterranean: addressing heterogeneity in distribution Jaume Forcada1,*, Manel Gazo2, Alex Aguilar2, Joan Gonzalvo2, Mar Fernández-Contreras2 1British Antarctic Survey, Natural Environment Research Council, Madingley Road, Cambridge CB3 0ET, United Kingdom 2Department of Animal Biology (Vertebrates), Faculty of Biology, University of Barcelona, 08071 Barcelona, Spain ABSTRACT: Line-transect estimators were developed to assess abundance of coastal dolphins Tur- siops truncatus and Stenella coeruleoalba encountered in low densities during aerial sighting sur- veys. The analysis improved on conventional approaches by objectively combining data from differ- ent species, survey areas and other covariates affecting dolphin detectability. Model selection and multimodel inference allowed robust estimates of precision in accounting for covariate selection uncertainty. These methods were used to estimate bottlenose dolphin abundance in NE Mediter- ranean waters that included a putative subpopulation in the Balearic Islands. Total abundance was estimated as 7654 (coefficient of variation, CV = 0.47; 95% CI = 1608 to 15 766) and the abundance in inshore waters of the Balearic Islands varied from 727 (CV = 0.47; 95% CI = 149 to 1481) dolphins in spring 2002 to 1333 (CV = 0.44; 95% CI = 419 to 2617) dolphins in autumn 2002, with an average estimate of 1030 (CV = 0.35; 95% CI = 415 to 1849). The results do not support an exclusively coastal Balearic Island subpopulation, but they strongly indicate that the islands contain critical habitats required for the conservation of the species. Given the observed decline of the species during the last few decades, conservation-oriented management should focus on reducing or eliminating adverse fishing interactions while key areas are protected from encroachment produced by human development. -

Stenella Coeruleoalba) from the Mediterranean Sea (Southern Italy)

Environmental Pollution 116 (2002) 265–271 www.elsevier.com/locate/envpol Accumulation and tissue distribution of mercury and selenium in striped dolphins (Stenella coeruleoalba) from the Mediterranean Sea (southern Italy) N. Cardellicchio *, A. Decataldo, A. Di Leo, A. Misino CNR — Istituto Sperimentale Talassografico, via Roma 3, I-74100 Taranto, Italy Received 13 October 2000; accepted 6 March 2001 Abstract Tissues and organs from Stenella coeruleoalba stranded along the Apulian coasts (southern Italy) during the period April–July 1991 were analyzed for their mercury and selenium content. Analysis showed considerable variations in the mercury concentration in the examined organs and tissues. The highest concentrations of mercury were found in the liver (from 2.27 to 374.50 mggÀ1 wet wt.). After the liver, lung, kidney, muscle and brain were the most contaminated, while the lowest mercury contamination was found in the melon. As mercury, the liver also showed the highest selenium levels. Liver samples were also analyzed for their methyl mercury contents. The role of selenium in detoxification process of methyl mercury has been discussed. Mercury concentrations related to geographic variations and pollution of the marine environment have been examined. The possible implications between mercury accumulation and dolphin death have also been discussed. # 2001 Elsevier Science Ltd. All rights reserved. Keywords: Mercury; Selenium; Mediterranean; Dolphin; Accumulation 1. Introduction monitoring researches on stranded animals both in the anatomo-pathological and in chemico-toxicological The study of mercury accumulation in dolphins is field have been carried out (Andre´ et al., 1991; Leonzio particularly interesting from the ecotoxicological point et al., 1992; Augier et al., 1993b; Cardellicchio, 1995; of view because of the position of these organisms at the Monaci et al., 1998; Capelli et al., 2000; Cardellicchio et end of the trophic networks. -

Z Dolphin Rescue

z Annual newsletter of the Blue World Institute for Marine Research and Conservation 2007. bottlenose dolphin can weigh up to 350kg which is normally supported by the water. The animal Dolphin rescue should be supported in a stretcher where possible and not left on any hard surfaces, this may dam- age the fragile bone structure of the ribs and the animal’s internal organs. Untrained help therefore from concerned citizens, although understand- able, should be avoided. Veterinary help should applied only by those individuals that have been trained on an internationally recognised cetacean medical course. The serious issue related to the transmission of diseases in cetacean species and populations and to their handling has been dis- cussed in detail at the 59th Annual Meeting of the Scientific Committee of the International Whaling Commission, which Croatia has recently joined. Blue World is a professional scientific organisation regularly participating in workshops and meetings organised by European and world experts trained in cetacean veterinary medicine. The above rec- ommendations follow the international standards of present knowledge on cetacean and dolphin Dolphin rescue is an unusually hard and extremely advice remains the same in this instance: please rescue techniques. In the past, Blue World has complex procedure. Unfortunately it is rarely suc- leave the animals alone, not to catch them or try proposed the creation of a national rescue centre cessful. Any attempt to rescue a whale or dolphin to get in contact with them, not to go into the for endangered and protected marine organisms, should be only carried out by expert personnel sea and swim with them, the best human help to particularly marine turtles and cetaceans, and a specially trained in this procedure. -

Miyazaki, N. Growth and Reproduction of Stenella Coeruleoalba Off The

GROWTH AND REPRODUCTION OF STENELLA COERULEOALBA OFF THE PACIFIC COAST OF JAPAN NOBUYUKI MIYAZAKI Department of Marine Sciences, University of the Ryukyus, Okinawa ABSTRACT This study is based on data from about five thousand specimens of S. coeruleoalba. Mean length at birth is 100 cm. Mean lengths at the age of 1 year and 2 years are 166 cm and 180 cm, respectively. The species starts feed ing on solid food at the age of 0.25 year (or 135 cm). Mean weaning age is about 1.5 years (or 174 cm). Mean testis weights at the attainment of puberty and sexual maturity of males are 6.8 g and 15.5 g, respectively. Mean ages at the attainment of puberty and sexual maturity of males are 6. 7 years (or 210 cm) and 8.7 years (or 219 cm), respectively. Females attain puberty and sexual maturity on the average at 7.1 years (or 209 cm) and 8.8 years (or 216 cm), respectively. There are three mating seasons in a year, from Feb ruary to May, from July to September, and in December. Mating season may occur at an interval from 4 to 5 months. The overall sex ratio (male/female) is 1.14. Sex ratio changes with age, from near parity at birth, indicating higher mortality rates for males. INTRODUCTION The striped dolphin, Stenella coeruleoalba are caught annually by the driving fishery or hand harpoons in the Pacific coast ofJapan (Ohsumi 1972, Miyazaki et al. 1974). According to Ohsumi (1972), Miyazaki et al. (1974), and Nishiwaki (1975), the striped dolphins caught in the Pacific coast of Japan are suggested to belong to one population.