Turnaround of Dean Foods

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ims List Sanitation Compliance and Enforcement Ratings of Interstate Milk Shippers April 2017

IMS LIST SANITATION COMPLIANCE AND ENFORCEMENT RATINGS OF INTERSTATE MILK SHIPPERS APRIL 2017 U.S. Department of Health and Human Services Public Health Service Food and Drug Administration Rules For Inclusion In The IMS List Interstate milk shippers who have been certified by State Milk sanitation authorities as having attained the milk sanitation compliance ratings are indicated in the following list. These ratings are based on compliance with the requirements of the USPHS/FDA Grade A Pasteurized Milk Ordinance and Grade A Condensed and Dry Milk Products and Condensed and Dry Whey and were made in accordance with the procedures set forth in Methods of Making Sanitation Rating of Milk Supplies. *Proposal 301 that was passed at 2001 NCIMS conference held May 5-10, 2001, in Wichita, Kansas and concurred with by FDA states: "Transfer Stations, Receiving Stations and Dairy Plants must achieve a sanitation compliance rating of 90 or better in order to be eligible for a listing in the IMS List. Sanitation compliance rating scores for Transfer and Receiving Stations and Dairy Plants will not be printed in the IMS List". Therefore, the publication of a sanitation compliance rating score for Transfer and Receiving Stations and Dairy Plants will not be printed in this edition of the IMS List. THIS LIST SUPERSEDES ALL LISTS WHICH HAVE BEEN ISSUED HERETOFORE ALL PRECEDING LISTS AND SUPPLEMENTS THERETO ARE VOID. The rules for inclusion in the list were formulated by the official representatives of those State milk sanitation agencies who have participated in the meetings of the National Conference of Interstate Milk Shipments. -

A Letter from Gregg Tanner, CEO

JULY ’16 A Letter from Gregg Tanner, CEO As we entered 2016, I lauded our employees’ hard work and expressed the importance of keeping our momentum going by executing our new Strategic Plan. Now, halfway through the year, I am very encouraged by the steps we’ve taken toward delivering the initiatives in our plan. Already this year we made strides against every one of our pillars: • Under the Build and Buy Strong Brands pillar, we • We made great strides continued building our brands with the national launch of toward Enhancing Future Caribou Iced Coffee, TruMoo Calcium Plus, and DairyPure Capabilities with new leadership Lactose Free milk. We also extended our DairyPure training that further develops line into creams and creamers. Within the Buy Strong our people. We also added an Brands portion of the pillar, we officially closed on our extended shelf life line at our Lynn, Mass., facility and are agreement to acquire Friendly’s Ice Cream. This move fills focused on expanding our warehouse capabilities. Earlier a manufacturing and retail void in the Northeast, and the this year, we launched our Purpose, Strengthening Lives brand is a perfect fit for Dean Foods for many reasons. Through the Goodness of Dairy, with meaningful employee One of the goals established in our Strategic Plan is to events in Salt Lake City, San Antonio, Athens (Tenn.), expand our ice cream portfolio, and Friendly’s is uniquely Springfield (Ohio) and Woodbury (Minn.). I greatly enjoyed qualified to help us achieve that goal. In addition to the those visits to the field and the opportunity to strengthen iconic Friendly’s reputation and strong brand awareness, our communities with donations to local hunger relief manufacturing diversity is also a key part of Friendly’s programs. -

STARBUCKS: from CROP to CUP APRIL 2015 the IMPACT of SOURCING INDUSTRIAL CONVENTIONAL MILK Updated January 2018

COALITION POWERED BY GREEN AMERICA STARBUCKS: FROM CROP TO CUP APRIL 2015 THE IMPACT OF SOURCING INDUSTRIAL CONVENTIONAL MILK updated January 2018 A MILK COMPANY Starbucks is one of the world’s most popular and widespread coffeehouse brands. It has over 22,000 cafes in 66 countries.1 In Manhattan alone there are 9 Starbucks per square mile.2 Starbucks built its reputation on delivering specialty coffee, putting a lot of energy into telling the story of its coffee from field to café. But what the company fails to address is the fact that each year, it purchases over 140,000,000 gallons of milk— enough to fill an Olympic-sized swimming pool 212 times.3 The fact is that Starbucks is a milk company as much or more than it is a coffee company. It is beyond time that it addresses the many negative impacts the industrial conventional dairy supply chain, from feed crop to cup, has on animal welfare and human and environmental health. If Starbucks’ goal, as stated on the company’s website, is to “share great coffee with [its] friends and help make the world a little better,” it is essential that the company transitions to organic milk.4 By setting the organic milk standard for coffee chains, Starbucks can demonstrate a serious commitment to providing environmentally and socially conscious products. Competitor com- panies like Pret A Manger are able to offer organic milk at a lower price than Starbucks charges for conventional dairy. It is our responsibility as consumers to vote with our dollars and use our voices to persuade the dairy industry to im- prove. -

EXHIBIT ITEM 1 SMA010 Proponent Cooperatives

EXHIBIT ITEM 1 SMA010 Proponent Cooperatives February 2004 Arkansas Dairy Cooperative Association, Inc. Floyd Wiedower, Manager P.O. Box 507 Damascus, Arkansas 72039 501-335-7204 501-335-7705 fax Dairy Farmers of America, Inc. Gary Hanman, Pres. & CEO P.O. Box 909700 Kansas City, Missouri 64190 816-801-6422 816-801-6423 fax Dairymen's Marketing Cooperative, Inc. Don Allen, General Manager 421 East State Street Mountain Grove, Missouri 65711 417-962-7460 417-962-6159 fax Lone Star Milk Producers, Inc. Jim Baird, Manager Route 1, Box 59B Windthorst, Texas 76389 940-378-2311 940-378-2751 fax Maryland & Virginia Milk Producers Cooperative Association, Inc. Jay Bryant, General Manager 1985 Isaac Newton Square West Reston, Virginia 20190 703-742-6800 703-742-7459 fax Southeast Milk, Inc. Calvin Covington, CEO P.O. Box 3790 Belleview, Florida 34421 352-245-2~,37 352-245-9434 fax EXHIBIT ITEM 2 SMA020 Producer Milk Deliveries Proponent Cooperatives and Others November 2003 F.O. 5 F.O. 7 Combined Total Order Producer Milk 507,412,336 593,836,792 1,101,249,128 Member Producer Milk Arkansas Dairy Coop. 13,933,382 13,933,382 Dairy Farmers of America 222,978,642 319,174,550 542,153,192 Dairymen's Marketing Coop. 6,235,057 6,235,057 Lone Star Milk Prod. 16,453,108 34,839,125 51,292,233 MD & VA Milk Prod. 80,473,502 22,119,702 102,593,204 / Southeast Milk 17,401,087 17,401,087 Tota___/I 319,905,252 413,702,903 733,608,155 Percent of Order Total 63.046% 69.666% 66.616% Other Cooperative Producer Milk Marketed Arkansas Dairy Coop. -

Federal Milk Order Distributing Plant Information for 2019 NOTE: "DIP" Indicates Debtor in Possession

Federal Milk Order Distributing Plant Information For 2019 NOTE: "DIP" indicates debtor in possession Pool Distributing Plants State County Plant Name City State ZipCode FIPS FIPS Cl. I Dftl. Jan-19 Feb-19 Mar-19 Apr-19 May-19 Jun-19 Jul-19 Aug-19 Sep-19 Oct-19 Nov-19 Dec-19 Agropur Grand Rapids MI 49548 26 081 1.80 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 Agropur Maplewood MN 55113 27 123 1.70 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 30 Alpenrose Dairy Portland OR 97298 41 051 1.90 124 124 124 124 124 124 124 124 124 124 124 124 Andersen Dairy Battle Ground WA 98604 53 011 1.90 124 124 124 124 124 124 124 124 124 124 124 124 Anderson-Erickson Dairy Des Moines IA 50317 19 153 1.80 32 32 32 32 32 32 32 32 32 32 32 32 Aurora Organic Dairy Platteville CO 80651 08 123 2.45 32 32 32 32 32 32 32 32 32 32 32 32 Blue Kingfisher dba Walmart Fort Wayne IN 46819 18 003 1.80 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 Boice Brothers Dairy Kingston NY 12401 36 111 2.80 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 Borden Dairy Cowarts AL 36321 01 069 4.30 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 Borden Dairy Miami FL 33164 12 025 6.00 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 Borden Dairy Winter Haven FL 33881 12 105 5.40 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 6 Borden Dairy London KY 40743 21 125 2.90 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 Borden Dairy Lafayette LA 70596 22 055 3.80 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 Borden Dairy Hattiesburg MS 39404 28 035 3.80 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 7 Borden Dairy Cincinnati OH 45215 39 061 2.20 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 Borden Dairy Cleveland OH 44111 39 035 2.00 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 33 Borden Dairy Charleston SC 29419 45 019 4.30 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 Borden Dairy Austin TX 78702 48 453 3.30 126 126 126 126 126 126 126 126 126 126 126 126 Borden Dairy Conroe TX 77305 48 339 3.60 126 126 126 126 126 126 126 126 126 126 126 126 Borden Dairy Dallas TX 75221 48 113 3.00 126 126 126 126 126 126 126 126 126 126 126 126 Braum's Tuttle OK 73089 40 051 2.60 32 32 32 32 32 32 32 32 32 32 32 32 Broadacre Dairies Powell TN 37849 47 093 3.20 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 5 Byrne Dairy Syracuse NY 13220 36 067 2.50 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 1 C. -

Dean Foods Successfully Implements C2CRM for Their HR Program

Case Study Dean Foods Successfully Implements C2CRM for Their HR Program Fluid Dairy Giant Streamlines Employee Change Request Management System Headquartered in Dallas, Dean Foods is a leading food and beverage company and the largest processor and direct-to-store distributor of fluid milk and other fluid dairy products in the United States. Their products are processed with the help of approximately 17,000 dedicated employees working in approximately 70 plants and close to 100 total locations across the U.S. The Business Problem The Human resources organization is responsible for managing and accurately keeping employee records up-to-date. The administration of these records were handled locally, typically by the 1 to 2 Human Resources personnel and a Business Partner coordinator at each location until the company evolved to a more centralized program. In an effort to better track all of the employee requests, a “Shared Services Center” was then implemented. Although all the requests were aggregated to one centralized location, there were still inefficiencies because the data entry process was manual and if key personnel were out sick or on vacation, critical work would not get done. According to Jessica Kosty, HRIS Manager at Dean Foods, “What was needed was a software that could automate data entry into a system that easily tracks all of their requests while notifying all the stakeholders of the completion of every stage in the process.” Why C2CRM? Leveraging the support module in C2CRM, HR is able to create allocate resources to address the increase of ticket processing. Once various types of tickets via the use and identification of multiple it was determined how successful the application was to their unique email boxes and track the history of work done during the life request process, the team expanded the use evolving from 1-2 of the ticket. -

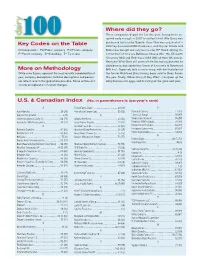

Key Codes on the Table More on Methodology Where Did They

Where did they go? Three companies depart the list this year, having been ac- quired early enough in 2007 to not be listed. Alto Dairy was Key Codes on the Table purchased last year by Saputo, Cass Clay was acquired at in 2007 by Associated Milk Producers, and Crystal Cream and C=Cooperative Pu=Public company Pr=Private company Butter was bought out early last year by HP Hood. Joining the P=Parent company S=Subsidiary T= Tie in rank list for the first time are BelGioso Cheese (No. 75), Ellsworth Creamery (84) and Roth Kase USA (96) all from Wisconsin. Next year Winn-Dixie will come off the list, having divested its dairy processing capabilities (some of it recently to Southeast More on Methodology Milk Inc.). Supervalu tells a similar story, with the final plant of While sales figures represent the most recently completed fiscal the former Richfood Dairy having been sold to Dean Foods year, company descriptions, facilities descriptions and person- this year. Finally, Wilcox Dairy of Roy, Wash., has given up the nel reflect recent changed where possible. Some entries will dairy business for eggs, and its listing will be gone next year. include an explanation of recent changes. U.S. & Canadian Index (No. in parentheses is last year’s rank) A Foster Farms Dairy ....................................... 50 (48) P Agri-Mark Inc. .............................................. 29 (29) Friendly Ice Cream Corp. ...............................55 (56) Parmalat Canada .........................................12 (13) Agropur Cooperative .........................................6 (9) G Perry’s Ice Cream ........................................ 97 (97) Anderson Erickson Dairy Co. ......................... 66 (71) Glanbia Foods Inc. ........................................ 23 (32) Plains Dairy Products ....................................95 (99) Associated Milk Producers Inc. -

Milkweed May 2006 Salvage

The Milkweed “Float like a butterfly, Dairy’s best information and insights sting like a bee.” Issue No. 475 • February 2019 This issue mailed on February 13 — Muhammad Ali Lost Export Markets Boost U.S. Cheese Inventories & Erode Prices by Jan Shepel focus on American-style cheeses, which include Cheese inventories in warehouses across the Cheddar – dairy’s price-setting benchmark variety. United States were being lowered in the early part of American cheese inventories started last year 2018, but after retaliatory tariffs were imposed by below 2017 levels – a perceived good indicator for trading partners late in 2018’s second quarter, those rising milk prices in the country. American cheese inventories jumped to levels significantly above year- inventories climbed less dramatically than in the pre- earlier levels. vious year, up to a July peak. American cheese in- The critical data for cheese inventories must ventories then dipped in August, before rising significantly above 2017 levels through November, Table 1 which is the last month for which data was available. Inventory numbers for 2014, 2015 and 2016 Cheese Inventories Versus were well below both 2017 and 2018 for the entire Exports After Tariffs year. In terms of total U.S. cheese production, 2018 data shows the numbers to be higher throughout the 2017 2018 year than all of those preceding years. But that’s not (Mill. lbs) (Mill. lbs) necessarily a a problem – due to solid, demand-driven output gains posted by Mozzarella and pizza cheese Jan. 752 740 during 2018. Comparing total January production in Roundup® herbicide’s active ingredient is Feb. -

(202) 514-2007 Tdd (202) 514-1888

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE AT TUESDAY, DECEMBER 18, 2001 (202) 514-2007 WWW.USDOJ.GOV TDD (202) 514-1888 JUSTICE DEPARTMENT REQUIRES SUIZA FOODS AND DEAN FOODS TO DIVEST 11 DAIRY PROCESSING PLANTS Divestitures in Alabama, Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, South Carolina, Virginia, Utah Will Protect Competition for Milk Sold through Schools and Retail Outlets WASHINGTON, D.C. -- The Department of Justice today announced that Suiza Foods Corporation and Dean Foods Company have agreed to sell 11 dairy processing plants in Alabama, Florida, Indiana, Kentucky, Ohio, South Carolina, Virginia, and Utah to resolve antitrust concerns about the companies’ pending merger. The Department said that without these divestitures, the merger would have reduced competition in markets for milk sold through schools and retail outlets in the areas around these plants. Suiza and Dean compete in these areas to provide milk to grocery stores, convenience stores, and other stores that sell directly to consumers. In many school districts, Suiza and Dean are currently the only two--or two of just three--companies that bid to deliver milk to schools. “These divestitures ensure that consumers of milk, an American staple, continue to get the benefits of competition--increased choices for consumers resulting in lower prices and better service,” said Charles A. James, Assistant Attorney General of the Department’s Antitrust Division. “Maintaining competition in the dairy industry is important for American consumers.” The Department is requiring the companies to divest seven Suiza and four Dean dairy processing plants. The Suiza dairies being divested are: Barber/Meadow Gold Dairies in Huntsville, AL; Velda Farms in Miami, FL; Velda Farms in Winter Haven, FL; Burger Dairy in - 2 - New Paris, IN; Flav-O-Rich in London, KY; Dairymen’s in Cleveland, OH; and Flav-O-Rich in Bristol, VA. -

Minnesota Dairy Plant List

Minnesota Dairy Plant List Dairy Plant Name Plant Plant City Product Number Category Agropur Inc. - Maplewood 27-421 Maplewood Fluid Agropur, Inc. - LeSueur 27-341 LeSueur Dry Agropur, Inc. - LeSueur Cheese 27-242 LeSueur Dry, Cheese Agropur, Inc. - Nicollet 27-339 Nicollet Dry Alemar Cheese 27-715 Mankato Cheese All American Foods - Waseca 27-671 Waseca Dry All American Foods Inc - Mankato 27-161 Mankato Dry All American Foods Inc - Mankato 27-670 Mankato Dry All American Foods Inc - Mankato 27-160 Mankato Dry Alto Cheese Inc 27-730 Pine City Packaging Cheese AmTech Ingredients LLC 27-721 Albert Lea Dry Associated Milk Producers, Inc. - New 27-031 New Ulm Butter Ulm Associated Milk Producers, Inc. - 27-506 Paynesville Dry, Cheese Paynesville Associated Milk Producers, Inc. - 27-355 Rochester Dry, Cheese, Ice Rochester Cream Autumnwood Farm LLC 27-974 Forest Lake Fluid, Ice Cream Bluegrass Proteins 27-171 Dawson Dry Bongards - Norwood 27-046 Norwood Cheese Product Bongards - Perham 27-777 Perham Dry, Cheese Dairy Plant Name Plant Plant City Product Number Category Buffalo Creek Creamery LLC 27-977 PLATO Cheese CityFoodStudio, LLC 27-174 Minneapolis Cheese Concept Processing LLC 27-100 Melrose Fluid, Butter Consolidated Containers 27-936 Moorhead Containers Dahl Tech 27-935 Stillwater Containers Dairiconcepts LP - Zumbrota 27-646 Zumbrota Dry, Cheese Dairiconcepts. - Dalbo 27-949 Dalbo Cheese Dairy Farmers of America - Winthrop 27-260 Winthrop Packaging Butter Dean Foods - Thief River Falls 27-378 Thief River Fluid, Ice Cream Falls Dean Foods - Woodbury 27-180 Woodbury Fluid Donnay Dairy 27-925 Kimball Cheese Eichers Farmstead Cheese 27-121 Avon Cheese Eichten Hidden Acres 27-701 Center City Cheese Faribault Dairy Co Inc. -

Dean Foods Company 2016 Annual Report

2016 Annual Report Dear Fellow Stockholders: There’s only one thing that excites me more than where Dean Foods is today, and that’s where we’re headed. This dynamic company has many opportunities ahead of it, and I’m humbled and excited to be the one privileged to lead Dean Foods into the future. STRONG PROGRESS IN 2016 TO EXPAND INTO 2017 No one can deny our momentum in 2016. We ended the year with our stock trading near its 52-week high while we continued to return dividends to our shareholders. We invested in the business and took important steps to support our future success. In 2016, we: Invested in the Launched new Acquired Friendly’s® Developed a joint Continued our DairyPure® and products. Ice Cream. venture with strong Food TruMoo® brands. DairyPure Lactose As planned, the Organic Valley®. Service momentum. We supported our Free and Caribou® acquisition of the Known as “Organic This is a growing power brands with & "! ,ƛ""4"/" leading Friendly’s Valley Fresh®, ” the joint channel in the food category-leading two new entries into brand grew our top venture leverages the and beverage industry advertising and built the dairy case. Our line and proved to be strength of the Organic that is now nearly the strategic marketing lactose-free milk marks accretive to earnings Valley brand and its same size as retail. partnerships with the 1%"Ɯ/01"51"+0&,+ while providing a solid high-quality organic We are among the Olympics, DreamWorks of the DairyPure platform for growth in *&)(4&1%1%"0&$+&Ɯ +1 biggest suppliers to the Pictures and Oreo brand into adjacent a strategic category. -

DRAFT DF-DFA APA Press Release

Dean Foods Enters Into Asset Purchase Agreement with Dairy Farmers of America Dairy Farmers of America to Serve as Proposed “Stalking Horse Bidder” in a Court-Supervised Sale Process for the Assets of Dean Foods DALLAS--(BUSINESS WIRE)--Dean Foods Company (“Dean Foods” or the “Company”) today announced that it and certain of its subsidiaries have entered into an asset purchase agreement with Dairy Farmers of America (“DFA”) through which DFA will acquire a substantial portion of Dean Foods’ business operations. Pursuant to the agreement, if consummated, DFA will acquire 44 of the Company’s fluid and frozen facilities and the real estate, inventory, equipment, and all other assets necessary to operate such facilities (the “Stalking Horse Assets”). “We have had a relationship with DFA over the past 20 years, and we are confident in their ability to succeed in the current market and serve our customers with the same commitment to quality and service they have come to expect,” said Eric Beringause, President and Chief Executive Officer of Dean Foods. Mr. Beringause continued, “I would like to thank all Dean Foods employees for their continued commitment to our customers, our partners and our company throughout this process. Their efforts have enabled us to continue providing an uninterrupted supply of high-quality dairy products, as well as support our dairy suppliers, vendors and other partners as we work to determine the best path forward for our business.” If approved by the Bankruptcy Court at a hearing scheduled for March 12, 2020 at 2:00 p.m. (prevailing Central Time), DFA will serve as a “stalking horse bidder” for the Stalking Horse Assets in a court- supervised sales process, whereby the agreement with DFA will set the floor for the sale of the Stalking Horse Assets.