Cupular Structure in Paleotropical Castanopsis (Fagaceae)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

"National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary."

Intro 1996 National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands The Fish and Wildlife Service has prepared a National List of Vascular Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1996 National Summary (1996 National List). The 1996 National List is a draft revision of the National List of Plant Species That Occur in Wetlands: 1988 National Summary (Reed 1988) (1988 National List). The 1996 National List is provided to encourage additional public review and comments on the draft regional wetland indicator assignments. The 1996 National List reflects a significant amount of new information that has become available since 1988 on the wetland affinity of vascular plants. This new information has resulted from the extensive use of the 1988 National List in the field by individuals involved in wetland and other resource inventories, wetland identification and delineation, and wetland research. Interim Regional Interagency Review Panel (Regional Panel) changes in indicator status as well as additions and deletions to the 1988 National List were documented in Regional supplements. The National List was originally developed as an appendix to the Classification of Wetlands and Deepwater Habitats of the United States (Cowardin et al.1979) to aid in the consistent application of this classification system for wetlands in the field.. The 1996 National List also was developed to aid in determining the presence of hydrophytic vegetation in the Clean Water Act Section 404 wetland regulatory program and in the implementation of the swampbuster provisions of the Food Security Act. While not required by law or regulation, the Fish and Wildlife Service is making the 1996 National List available for review and comment. -

Quercus Robur (Fagaceae)

Quercus robur (Fagaceae) The map description EEBIO area The integrated map shows the distribution and changes in the areal’s boundaries of pedunculate oak (Quercus robur). Q. robur is the dominant forest- formative species in the belt of broadleaf and mixed 4 needleleaf-broadleaf forests in the plains of the European part of the former USSR (Sokolov et al. 1977). In the northern part of its areal Q. robur grows in river valleys. In the central part, it forms mixed forests with Picea abies; closer to the south – a belt of broadleaf forests where Q. robur dominates. At the areal’s south boundary it forms small (marginal) forests in ravines and flood-plains (Atlas of Areals and Resources… , 1976). Q. robur belongs to the thermophilic species. The low temperature bound of possible occurrence of oak forests is marked by an average annual of 2?C l (http://www.forest.ru – in Russian). Therefore, l l l l l l hypotretically, oak areal boundaries will shift along l ll l l l l l l l with the changes in the average annual temperature. l l l l l l l l l l l For Yearly map of averaged mean annual air l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l lll temperature (Afonin A., Lipiyaynen K., Tsepelev V., l l l l l l l ll ll l l l 2005) see http://www.agroatlas.spb.ru Climate. l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l Oak forests are of great importance for the water l l l l l ll l lll l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l regime and soil structure, especially on the steep l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l l slopes of river valleys and in forest-poor areas. -

5 Fagaceae Trees

CHAPTER 5 5 Fagaceae Trees Antoine Kremerl, Manuela Casasoli2,Teresa ~arreneche~,Catherine Bod6n2s1, Paul Sisco4,Thomas ~ubisiak~,Marta Scalfi6, Stefano Leonardi6,Erica ~akker~,Joukje ~uiteveld', Jeanne ~omero-Seversong, Kathiravetpillai Arumuganathanlo, Jeremy ~eror~',Caroline scotti-~aintagne", Guy Roussell, Maria Evangelista Bertocchil, Christian kxerl2,Ilga porth13, Fred ~ebard'~,Catherine clark15, John carlson16, Christophe Plomionl, Hans-Peter Koelewijn8, and Fiorella villani17 UMR Biodiversiti Genes & Communautis, INRA, 69 Route d'Arcachon, 33612 Cestas, France, e-mail: [email protected] Dipartimento di Biologia Vegetale, Universita "La Sapienza", Piazza A. Moro 5,00185 Rome, Italy Unite de Recherche sur les Especes Fruitikres et la Vigne, INRA, 71 Avenue Edouard Bourlaux, 33883 Villenave d'Ornon, France The American Chestnut Foundation, One Oak Plaza, Suite 308 Asheville, NC 28801, USA Southern Institute of Forest Genetics, USDA-Forest Service, 23332 Highway 67, Saucier, MS 39574-9344, USA Dipartimento di Scienze Ambientali, Universitk di Parma, Parco Area delle Scienze 1lIA, 43100 Parma, Italy Department of Ecology and Evolution, University of Chicago, 5801 South Ellis Avenue, Chicago, IL 60637, USA Alterra Wageningen UR, Centre for Ecosystem Studies, P.O. Box 47,6700 AA Wageningen, The Netherlands Department of Biological Sciences, University of Notre Dame, Notre Dame, IN 46556, USA lo Flow Cytometry and Imaging Core Laboratory, Benaroya Research Institute at Virginia Mason, 1201 Ninth Avenue, Seattle, WA 98101, -

Nothofagus, Key Genus of Plant Geography, in Time

Nothofagus, key genus of plant geography, in time and space, living and fossil, ecology and phylogeny C.G.G.J. van Steenis Rijksherbarium, Leyden, Holland Contents Summary 65 1. Introduction 66 New 2. Caledonian species 67 of and Caledonia 3. Altitudinal range Nothofagus in New Guinea New 67 Notes of 4. on distribution Nothofagus species in New Guinea 70 5. Dominance of Nothofagus 71 6. Symbionts of Nothofagus 72 7. Regeneration and germination of Nothofagus in New Guinea 73 8. Dispersal in Nothofagus and its implications for the genesis of its distribution 74 9. The South Pacific and subantarctic climate, present and past 76 10. The fossil record 78 of in time and 11. Phylogeny Nothofagus space 83 12. Bi-hemispheric ranges homologous with that of Fagoideae 89 13. Concluding theses 93 Acknowledgements 95 Bibliography 95 Postscript 97 Summary Data are given on the taxonomy and ecology of the genus. Some New Caledonian in descend the lowland. Details the distri- species grow or to are provided on bution within New Guinea. For dominance of Nothofagus, and Fagaceae in general, it is suggested that this. Some in New possibly symbionts may contribute to notes are made onregeneration and germination Guinea. A is devoted a discussion of which to be with the special chapter to dispersal appears extremely slow, implication that Nothofagus indubitably needs land for its spread, and has needed such for attaining its colossal range, encircling onwards of New Guinea the South Pacific (fossil pollen in Antarctica) to as far as southern South America. Map 1. An is other chapter devoted to response ofNothofagus to the present climate. -

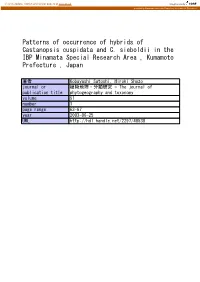

Patterns of Occurrence of Hybrids of Castanopsis Cuspidata and C

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Kanazawa University Repository for Academic Resources Patterns of occurrence of hybrids of Castanopsis cuspidata and C. sieboldii in the IBP Minamata Special Research Area , Kumamoto Prefecture , Japan 著者 Kobayashi Satoshi, Hiroki Shozo journal or 植物地理・分類研究 = The journal of publication title phytogeography and toxonomy volume 51 number 1 page range 63-67 year 2003-06-25 URL http://hdl.handle.net/2297/48538 Journal of Phytogeography and Taxonomy 51 : 63-67, 2003 !The Society for the Study of Phytogeography and Taxonomy 2003 Satoshi Kobayashi and Shozo Hiroki : Patterns of occurrence of hybrids of Castanopsis cuspidata and C. sieboldii in the IBP Minamata Special Research Area , Kumamoto Prefecture , Japan Graduate School of Human Informatics, Nagoya University, Chikusa-Ku, Nagoya 464―8601, Japan Castanopsis cuspidata(Thunb.)Schottky and However, it is difficult to identify the hybrids by C. sieboldii(Makino)Hatus. ex T. Yamaz. et nut morphology alone, because the nut shapes of Mashiba are dominant components of the ever- the 2 species are variable and can overlap with green broad-leaved forests of southwestern Ja- each other. Kobayashi et al.(1998)showed that pan, including parts of Honshu, Kyushu and hybrids have a chimeric structure of both 1 and Shikoku but excluding the Ryukyu Islands(Hat- 2 epidermal layers within a leaf. These morpho- tori and Nakanishi 1983).Although these 2 Cas- logical differences among C. cuspidata, C. sie- tanopsis species are both climax species, it is boldii and their hybrid can be confirmed by ge- very difficult to distinguish them because of the netic differences in nuclear species-specific existence of an intermediate type(hybrid). -

Diversity of Wisconsin Rosids

Diversity of Wisconsin Rosids . oaks, birches, evening primroses . a major group of the woody plants (trees/shrubs) present at your sites The Wind Pollinated Trees • Alternate leaved tree families • Wind pollinated with ament/catkin inflorescences • Nut fruits = 1 seeded, unilocular, indehiscent (example - acorn) *Juglandaceae - walnut family Well known family containing walnuts, hickories, and pecans Only 7 genera and ca. 50 species worldwide, with only 2 genera and 4 species in Wisconsin Carya ovata Juglans cinera shagbark hickory Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Leaves pinnately compound, alternate (walnuts have smallest leaflets at tip) Leaves often aromatic from resinous peltate glands; allelopathic to other plants Carya ovata Juglans cinera shagbark hickory Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family The chambered pith in center of young stems in Juglans (walnuts) separates it from un- chambered pith in Carya (hickories) Juglans regia English walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Trees are monoecious Wind pollinated Female flower Male inflorescence Juglans nigra Black walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Male flowers apetalous and arranged in pendulous (drooping) catkins or aments on last year’s woody growth Calyx small; each flower with a bract CA 3-6 CO 0 A 3-∞ G 0 Juglans cinera Butternut, white walnut *Juglandaceae - walnut family Female flowers apetalous and terminal Calyx cup-shaped and persistant; 2 stigma feathery; bracted CA (4) CO 0 A 0 G (2-3) Juglans cinera Juglans nigra Butternut, white -

NGS Report Explained

Jonah Ventures NGS Report Files Explained Summary data The % of base pairs in the Sample identifiers Exact Sequence Variant sequence that match to the The detected Exact Sequence Variant Consensus Taxonomy The detected Numbers after the decimal point unique identifier species in the library. sequence. represent lab replicates of the same Taxonomic ranking from the Number of species sample. library matched to each sequence. matching the sequence at a given level. ESV Family Genus Species %match # Species Sequence S10001.1 S10002.1 S10003.1 S10003.2 ESV_000080 Fagaceae Quercus NA 100 7 AAAAAG… 3066 1340 5780 3462 ESV_000818 Orobanchaceae Orthocarpus Orthocarpus luteus 100 1 AAAAAG… 0 2582 249 0 ESV_000006 Poaceae NA NA 100 77 GAAAAG… 584 101 0 1039 ESV_000050 Poaceae NA NA 100 12 GAAAAG… 1328 0 0 0 ESV_000308 Polygonaceae Polygonum Polygonum humifusum 100 2 AAAAAG… 902 0 0 278 ESV_000027 Polygonaceae Eriogonum Eriogonum umbellatum 100 1 ATAAAG… 341 124 282 381 ESV_000520 Polygonaceae Fallopia Fallopia multiflora 99 1 AAAAAG… 126 0 0 994 “NA” at a taxonomic ranks means multiple species present in The number in each cell is the absolute number of the sample differ in that taxonomic rank times a given sequence was read by the sequencer. ESV detail Exact Sequence Variant The % of base pairs in the sequence that match to the species. Index identification number. that match to the species. Each sample has an Species Taxonomy 100% indicates all base pairs matched individual index number. ESV GB_ID Phylum Order Family Genus Species %match ESV_000818 -

Ray Imaging of a Dichasium Cupule of Castanopsis from Eocene Baltic Amber

RESEARCH ARTICLE Synchrotron X- ray imaging of a dichasium cupule of Castanopsis from Eocene Baltic amber Eva-Maria Sadowski1,4 , Jörg U. Hammel2 , and Thomas Denk3 Manuscript received 30 May 2018; revision accepted 6 September PREMISE OF THE STUDY: The Eocene Baltic amber deposit represents the largest 2018. accumulation of fossil resin worldwide, and hundreds of thousands of entrapped 1 Department of Geobiology, University of Göttingen, arthropods have been recovered. Although Baltic amber preserves delicate plant Goldschmidtstraße 3, 37077 Göttingen, Germany structures in high fidelity, angiosperms of the “Baltic amber forest” remain poorly studied. 2 Institute of Materials Research, Helmholtz-Zentrum Geesthacht, We describe a pistillate partial inflorescence of Castanopsis (Fagaceae), expanding the Max-Planck-Str. 1, 21502 Geesthacht, Germany knowledge of Fagaceae diversity from Baltic amber. 3 Department of Palaeobiology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, 10405 Stockholm, Sweden METHODS: The amber specimen was investigated using light microscopy and 4 Author for correspondence (e-mail: eva-maria.sadowski@ synchrotron- radiation- based X- ray micro- computed tomography (SRμCT). geo.uni-goettingen.de) KEY RESULTS: The partial inflorescence is a cymule, consisting of an involucre of scales Citation: Sadowski, E.-M., J. U. Hammel, and T. Denk. 2018. Synchrotron X- ray imaging of a dichasium cupule of Castanopsis that surround all four pistillate flowers, indicating a dichasium cupule. Subtending bracts from Eocene Baltic amber. American Journal of Botany 105(12): are basally covered with peltate trichomes. Flowers possess an urecolate perianth of 2025–2036. six nearly free lobes, 12 staminodia hidden by the perianth, and a tri-locular ovary that doi:10.1002/ajb2.1202 is convex- triangular in cross section. -

Assessing Restoration Potential of Fragmented and Degraded Fagaceae Forests in Meghalaya, North-East India

Article Assessing Restoration Potential of Fragmented and Degraded Fagaceae Forests in Meghalaya, North-East India Prem Prakash Singh 1,2,* , Tamalika Chakraborty 3, Anna Dermann 4 , Florian Dermann 4, Dibyendu Adhikari 1, Purna B. Gurung 1, Saroj Kanta Barik 1,2, Jürgen Bauhus 4 , Fabian Ewald Fassnacht 5, Daniel C. Dey 6, Christine Rösch 7 and Somidh Saha 4,7,* 1 Department of Botany, North-Eastern Hill University, Shillong 793022, India; [email protected] (D.A.); [email protected] (P.B.G.); [email protected] (S.K.B.) 2 CSIR-National Botanical Research Institute, Council of Scientific & Industrial Research, Rana Pratap Marg, Lucknow 226001, Uttar Pradesh, India 3 Institute of Forest Ecosystems, Thünen Institute, Alfred-Möller-Str. 1, House number 41/42, D-16225 Eberswalde, Germany; [email protected] 4 Chair of Silviculture, University of Freiburg, Tennenbacherstr. 4, D-79085 Freiburg, Germany; anna-fl[email protected] (A.D.); fl[email protected] (F.D.); [email protected] (J.B.) 5 Institute for Geography and Geoecology, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Kaiserstr. 12, D-76131 Karlsruhe, Germany; [email protected] 6 Northern Research Station, USDA Forest Service, 202 Natural Resources Building, Columbia, MO 65211-7260, USA; [email protected] 7 Institute for Technology Assessment and Systems Analysis, Karlsruhe Institute of Technology, Karlstr. 11, D-76133 Karlsruhe, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: prem12fl[email protected] (P.P.S.); [email protected] (S.S.) Received: 5 August 2020; Accepted: 16 September 2020; Published: 19 September 2020 Abstract: The montane subtropical broad-leaved humid forests of Meghalaya (Northeast India) are highly diverse and situated at the transition zone between the Eastern Himalayas and Indo-Burma biodiversity hotspots. -

Flora of South Australia 5Th Edition | Edited by Jürgen Kellermann

Flora of South Australia 5th Edition | Edited by Jürgen Kellermann KEY TO FAMILIES1 J.P. Jessop2 The sequence of families used in this Flora follows closely the one adopted by the Australian Plant Census (www.anbg.gov. au/chah/apc), which in turn is based on that of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG III 2009) and Mabberley’s Plant Book (Mabberley 2008). It differs from previous editions of the Flora, which were mainly based on the classification system of Engler & Gilg (1919). A list of all families recognised in this Flora is printed in the inside cover pages with families already published highlighted in bold. The up-take of this new system by the State Herbarium of South Australia is still in progress and the S.A. Census database (www.flora.sa.gov.au/census.shtml) still uses the old classification of families. The Australian Plant Census web-site presents comparison tables of the old and new systems on family and genus level. A good overview of all families can be found in Heywood et al. (2007) and Stevens (2001–), although these authors accept a slightly different family classification. A number of names with which people using this key may be familiar but are not employed in the system used in this work have been included for convenience and are enclosed on quotation marks. 1. Plants reproducing by spores and not producing flowers (“Ferns and lycopods”) 2. Aerial shoots either dichotomously branched, with scale leaves and 3-lobed sporophores or plants with fronds consisting of a simple or divided sterile blade and a simple or branched spikelike sporophore .................................................................................. -

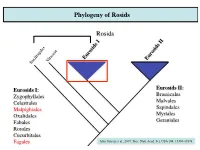

Phylogeny of Rosids! ! Rosids! !

Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Alnus - alders A. rubra A. rhombifolia A. incana ssp. tenuifolia Alnus - alders Nitrogen fixation - symbiotic with the nitrogen fixing bacteria Frankia Alnus rubra - red alder Alnus rhombifolia - white alder Alnus incana ssp. tenuifolia - thinleaf alder Corylus cornuta - beaked hazel Carpinus caroliniana - American hornbeam Ostrya virginiana - eastern hophornbeam Phylogeny of Rosids! Rosids! ! ! ! ! Eurosids I Eurosids II Vitaceae Saxifragales Eurosids I:! Eurosids II:! Zygophyllales! Brassicales! Celastrales! Malvales! Malpighiales! Sapindales! Oxalidales! Myrtales! Fabales! Geraniales! Rosales! Cucurbitales! Fagales! After Jansen et al., 2007, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 104: 19369-19374! Fagaceae (Beech or Oak family) ! Fagaceae - 9 genera/900 species.! Trees or shrubs, mostly northern hemisphere, temperate region ! Leaves simple, alternate; often lobed, entire or serrate, deciduous -

Fagus Sylvatica - European Beech (Fagaceae) ------Fagus Sylvatica Is a Graceful, Slow-Growing, Large Tree Texture for Shade Or Specimen Usage

Fagus sylvatica - European Beech (Fagaceae) ------------------------------------------------------------------------------ Fagus sylvatica is a graceful, slow-growing, large tree Texture for shade or specimen usage. European Beech has many -medium to fine texture in foliage and fine-textured cultivars available for growth habit and foliage when bare variation. -thick density in foliage and when bare (except in youth, when the branching is sparse and quite open) FEATURES Assets Form -dense shade at maturity -large deciduous tree -branching nearly to the ground -maturing at 60' tall x 40' wide -graceful or architecturally interesting branching, -upright oval depending upon cultivar growth habit -smooth medium-gray bark for the species -several foliage and growth habit variants and many -nuts attract wildlife in autumn cultivars Liabilities -slow growth -slow growth rate -awkwardly and sparsely branched in youth Culture -not urban tolerant -full sun to -surface roots with age partial shade Habitat -performs best -Zones 5 to 7 in deep, moist, -Native to Europe well-drained, slightly acid SELECTIONS soils Alternates -propagated by -large shade or specimen trees with alternative broadleaf grafting or foliage colors (Acer platanoides 'Crimson King', seeds 'Crimson Sentry', 'Drummondi', etc., Liriodendron -Beech Family, with no disease or pest problems of tulipifera 'Aureomarginatum' ; other species of trees significance, but does not respond well to urban stresses exist with this trait, but they are often weak-growing) -many cultivars are allowed