Rural Urban Migration with Reference to Raigad District

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Integrated State Water Plan for West Flowing River Basin in Maharashtra Volume Ii: Integrated Plan

INTEGRATED STATE WATER PLAN FOR WEST FLOWING RIVER BASIN IN MAHARASHTRA VOLUME II: INTEGRATED PLAN GOVERNMENT OF MAHARASHTRA WATER RESOURCES DEPARTMENT INTEGRATED STATE WATER PLAN FOR WEST FLOWING RIVER BASIN IN MAHARASHTRA VOLUME – II : INTEGRATED PLAN KOKAN IRRIGATION DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, THANE MARCH 2018 1 GOVERNMENT OF MAHARASHTRA WATER RESOURCES DEPARTMENT INTEGRATED STATE WATER PLAN FOR WEST FLOWING RIVER BASIN IN MAHARASHTRA VOLUME II: INTEGRATED PLAN INTEGRATED STATE WATER PLAN FOR WEST FLOWING RIVER BASIN IN MAHARASHTRA VOLUME - II INTEGRATED PLAN (Upto year 2030) CHAPTERS 12-25 KOKAN IRRIGATION DEVELOPMENT CORPORATION, THANE GOVERNMENT OF MAHARASHTRA WATER RESOURCES DEPARTMENT MARCH 2018 2 GOVERNMENT OF MAHARASHTRA WATER RESOURCES DEPARTMENT INTEGRATED STATE WATER PLAN FOR WEST FLOWING RIVER BASIN IN MAHARASHTRA VOLUME II: INTEGRATED PLAN Contents Contents ................................................................................................................................................... 3 Glossary ................................................................................................................................................. 12 12 Water for Energy ............................................................................................................................... 12.1 Conventional energy projects ............................................................................................ 25 12.1.1 Hydro power generation .......................................................................................... -

Sr. No. College Name University Name Taluka District JD Region

Non-Aided College List Sr. College Name University Name Taluka District JD Region Correspondence College No. Address Type 1 Shri. KGM Newaskar Sarvajanik Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Pandit neheru Hindi Non-Aided Trust's K.G. College of Arts & Pune University, ar ar vidalaya campus,Near Commerece, Ahmednagar Pune LIC office,Kings Road Ahmednagrcampus,Near LIC office,Kings 2 Masumiya College of Education Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune wable Non-Aided Pune University, ar ar colony,Mukundnagar,Ah Pune mednagar.414001 3 Janata Arts & Science Collge Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune A/P:- Ruichhattishi ,Tal:- Non-Aided Pune University, ar ar Nagar, Dist;- Pune Ahmednagarpin;-414002 4 Gramin Vikas Shikshan Sanstha,Sant Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune At Post Akolner Tal Non-Aided Dasganu Arts, Commerce and Science Pune University, ar ar Nagar Dist Ahmednagar College,Akolenagar, Ahmednagar Pune 414005 5 Dr.N.J.Paulbudhe Arts, Commerce & Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune shaneshwar nagarvasant Non-Aided Science Women`s College, Pune University, ar ar tekadi savedi Ahmednagar Pune 6 Xavier Institute of Natural Resource Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Behind Market Yard, Non-Aided Management, Ahmednagar Pune University, ar ar Social Centre, Pune Ahmednagar. 7 Shivajirao Kardile Arts, Commerce & Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag Pune Jambjamb Non-Aided Science College, Jamb Kaudagav, Pune University, ar ar Ahmednagar-414002 Pune 8 A.J.M.V.P.S., Institute Of Hotel Savitribai Phule Ahmednag Ahmednag -

Siva Chhatrapati, Being a Translation of Sabhasad Bakhar with Extracts from Chitnis and Sivadigvijaya, with Notes

SIVA CHHATRAPATI Extracts and Documents relating to Maratha History Vol. I SIVA CHHATRAPATI BEING A TRANSLATION OP SABHASAD BAKHAR WITH EXTRACTS FROM CHITNIS AND SIVADIGVTJAYA, WITH NOTES. BY SURENDRANATH SEN, M.A., Premchaxd Roychand Student, Lectcrer in MarItha History, Calcutta University, Ordinary Fellow, Indian Women's University, Poona. Formerly Professor of History and English Literature, Robertson College, Jubbulpore. Published by thz UNIVERSITY OF CALCUTTA 1920 PRINTED BY ATCLCHANDKA BHATTACHABYYA, AT THE CALCUTTA UNIVEB8ITY PEE 88, SENATE HOUSE, CALCUTTA " WW**, #rf?fW rT, SIWiMfT, ^R^fa srre ^rtfsre wwf* Ti^vtm PREFACE The present volume is the first of a series intended for those students of Maratha history who do not know Marathi. Original materials, both published and unpublished, have been accumulating for the last sixtv years and their volume often frightens the average student. Sir Asutosh Mookerjee, therefore, suggested that a selection in a handy form should be made where all the useful documents should be in- cluded. I must confess that no historical document has found a place in the present volume, but I felt that the chronicles or bakhars could not be excluded from the present series and I began with Sabhasad bakhar leaving the documents for a subsequent volume. This is by no means the first English rendering of Sabhasad. Jagannath Lakshman Mankar translated Sabhasad more than thirty years ago from a single manuscript. The late Dr. Vincent A. Smith over- estimated the value of Mankar's work mainly because he did not know its exact nature. A glance at the catalogue of Marathi manuscripts in the British Museum might have convinced him that the original Marathi Chronicle from which Mankar translated has not been lost. -

Seminar Report

Two day Awareness Seminar on Green Chemistry & Engineering Date : 22ⁿ - 23 April, 2014 Venue : Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar University (DBATU), Lonere, Raigad Seminar Report Supporters : Department of Chemical and Petrochemicals, Government Of India INTRODUCTION The Two-day Awareness Seminar on Green Chemistry & Engineering, organised on the occasion of World Earth Day (22nd April), at Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar Technological University (DBATU), Lonere, Dist. Raigad, was successfully concluded on 23rd April 2014. The objecves of the Seminar were as follows: - To create awareness of Green Chemistry and Engineering, with specific focus on the 12 Principles of Green Chemistry - To introduce emerging trends and technologies on green chemistry and engineering - To connect the parcipants to various soluon and technology provider companies - To learn from success case-studies and industry sharing ORGANISERS, SUPPORTERS & PARTNERS The Seminar was jointly organised by the Indian Chemical Council (ICC) and the Green ChemisTree Foundaon (GCF) with support from Dept. of Chemicals & Petrochemicals (DCPC), Govt. of India; Maharashtra Polluon Control Board (MPCB); Mahad Manufacturers Associaon (MMA); Roha Industries Associaon (RIA); and Industry Partners such as Clariant Chemicals India Pvt. Ltd and Pidilite Industries Ltd. PARTICIPATION The Seminar was well aended by over 80 Plant, Operaons and EHS personnel of more than 50 chemical companies located in the largest Industrial corridor of Maharashtra. The representaon was fairly distributed amongst Chiplun, Lote, Mahad, Roha, Patalganga and Taloja Industrial associaons, largely consisng of companies from Mahad and Roha regions. The companies parcipated were a mix of MNC (20%), Large (30%) and SME categories (50%). SPEAKERS, CONTEXT & CONTENT Leading academia experts who contributed to the deliberaon includes Prof. -

Sources of Maratha History: Indian Sources

1 SOURCES OF MARATHA HISTORY: INDIAN SOURCES Unit Structure : 1.0 Objectives 1.1 Introduction 1.2 Maratha Sources 1.3 Sanskrit Sources 1.4 Hindi Sources 1.5 Persian Sources 1.6 Summary 1.7 Additional Readings 1.8 Questions 1.0 OBJECTIVES After the completion of study of this unit the student will be able to:- 1. Understand the Marathi sources of the history of Marathas. 2. Explain the matter written in all Bakhars ranging from Sabhasad Bakhar to Tanjore Bakhar. 3. Know Shakavalies as a source of Maratha history. 4. Comprehend official files and diaries as source of Maratha history. 5. Understand the Sanskrit sources of the Maratha history. 6. Explain the Hindi sources of Maratha history. 7. Know the Persian sources of Maratha history. 1.1 INTRODUCTION The history of Marathas can be best studied with the help of first hand source material like Bakhars, State papers, court Histories, Chronicles and accounts of contemporary travelers, who came to India and made observations of Maharashtra during the period of Marathas. The Maratha scholars and historians had worked hard to construct the history of the land and people of Maharashtra. Among such scholars people like Kashinath Sane, Rajwade, Khare and Parasnis were well known luminaries in this field of history writing of Maratha. Kashinath Sane published a mass of original material like Bakhars, Sanads, letters and other state papers in his journal Kavyetihas Samgraha for more eleven years during the nineteenth century. There is much more them contribution of the Bharat Itihas Sanshodhan Mandal, Pune to this regard. -

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No

Reg. No Name in Full Residential Address Gender Contact No. Email id Remarks 20001 MUDKONDWAR SHRUTIKA HOSPITAL, TAHSIL Male 9420020369 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PRASHANT NAMDEORAO OFFICE ROAD, AT/P/TAL- GEORAI, 431127 BEED Maharashtra 20002 RADHIKA BABURAJ FLAT NO.10-E, ABAD MAINE Female 9886745848 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 PLAZA OPP.CMFRI, MARINE 8281300696 DRIVE, KOCHI, KERALA 682018 Kerela 20003 KULKARNI VAISHALI HARISH CHANDRA RESEARCH Female 0532 2274022 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 MADHUKAR INSTITUTE, CHHATNAG ROAD, 8874709114 JHUSI, ALLAHABAD 211019 ALLAHABAD Uttar Pradesh 20004 BICHU VAISHALI 6, KOLABA HOUSE, BPT OFFICENT Female 022 22182011 / NOT RENEW SHRIRANG QUARTERS, DUMYANE RD., 9819791683 COLABA 400005 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20005 DOSHI DOLLY MAHENDRA 7-A, PUTLIBAI BHAVAN, ZAVER Female 9892399719 [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 ROAD, MULUND (W) 400080 MUMBAI Maharashtra 20006 PRABHU SAYALI GAJANAN F1,CHINTAMANI PLAZA, KUDAL Female 02362 223223 / [email protected] RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 OPP POLICE STATION,MAIN ROAD 9422434365 KUDAL 416520 SINDHUDURG Maharashtra 20007 RUKADIKAR WAHEEDA 385/B, ALISHAN BUILDING, Female 9890346988 DR.NAUSHAD.INAMDAR@GMA RENEWAL UP TO 26/04/2018 BABASAHEB MHAISAL VES, PANCHIL NAGAR, IL.COM MEHDHE PLOT- 13, MIRAJ 416410 SANGLI Maharashtra 20008 GHORPADE TEJAL A-7 / A-8, SHIVSHAKTI APT., Male 02312650525 / NOT RENEW CHANDRAHAS GIANT HOUSE, SARLAKSHAN 9226377667 PARK KOLHAPUR Maharashtra 20009 JAIN MAMTA -

MUMBAI an EMERGING HUB for NEW BUSINESSES & SUPERIOR LIVING 2 Raigad: Mumbai - 3.0

MUMBAI AN EMERGING HUB FOR NEW BUSINESSES & SUPERIOR LIVING 2 Raigad: Mumbai - 3.0 FOREWORD Anuj Puri ANAROCK Group Group Chairman With the island city of Mumbai, Navi Mumbai contribution of the district to Maharashtra. Raigad and Thane reaching saturation due to scarcity of is preparing itself to contribute significantly land parcels for future development, Raigad is towards Maharashtra’s aim of contributing US$ expected to emerge as a new destination offering 1 trillion to overall Indian economy by 2025. The a fine balance between work and pleasure. district which is currently dominated by blue- Formerly known as Kolaba, Raigad is today one collared employees is expected to see a reverse of the most prominent economic districts of the in trend with rising dominance of white-collared state of Maharashtra. The district spans across jobs in the mid-term. 7,152 sq. km. area having a total population of 26.4 Lakh, as per Census 2011, and a population Rapid industrialization and urbanization in density of 328 inhabitants/sq. km. The region Raigad are being further augmented by massive has witnessed a sharp decadal growth of 19.4% infrastructure investments from the government. in its overall population between 2001 to 2011. This is also attributing significantly to the overall Today, the district boasts of offering its residents residential and commercial growth in the region, a perfect blend of leisure, business and housing thereby boosting overall real estate growth and facilities. uplifting and improving the quality of living for its residents. Over the past few years, Raigad has become one of the most prominent districts contributing The report titled ‘Raigad: Mumbai 3.0- An significantly to Maharashtra’s GDP. -

Impact of Changes in Geotechnical Properties on the Serviceability of Cantilever Retaining Structure in Lateritic Soil

International Research Journal of Engineering and Technology (IRJET) e-ISSN: 2395-0056 Volume: 06 Issue: 04 | Apr 2019 www.irjet.net p-ISSN: 2395-0072 Impact of Changes in Geotechnical Properties on the Serviceability of Cantilever Retaining Structure in Lateritic Soil Pawar Nilesh Suresh1, Jadhav Hanmant Shamrao2 1M. Tech. student, Dept. of Civil-Structural Engineering, Rajarambapu Institute of Technology (An Autonomous Institute, Affiliated to Shivaji University), Islampur, Maharashtra, India 2Professor, Dept. of Civil-Structural Engineering¸ Rajarambapu Institute of Technology (An Autonomous Institute, Affiliated to Shivaji University), Islampur, Maharashtra, India ---------------------------------------------------------------------***---------------------------------------------------------------------- Abstract - In this paper the comparative study of compressibility or strength of the soil always affect the geotechnical properties of lateritic soil as input design design. Lack of understanding of the properties of the soil parameters in pre and post construction condition of earth can lead to the construction errors or structural failure. The retaining structure is studied and its impact on serviceability ERS design must satisfy two major requirements i.e. internal is noted. Permanent RCC earth retaining structures (ERS) are stability which is ensured by sufficient resistance against constructed for total lifespan of 30-60 years but generally in bending moment and shear force and external stability most of cases, it cannot withstand -

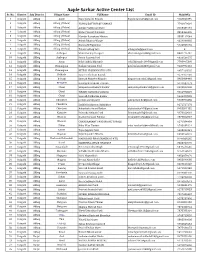

Aaple Sarkar Active Center List Sr

Aaple Sarkar Active Center List Sr. No. District Sub District Village Name VLEName Email ID MobileNo 1 Raigarh Alibag Akshi Sagar Jaywant Kawale [email protected] 9168823459 2 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) VISHAL DATTATREY GHARAT 7741079016 3 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Ashish Prabhakar Mane 8108389191 4 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Kishor Vasant Nalavade 8390444409 5 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Mandar Ramakant Mhatre 8888117044 6 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Ashok Dharma Warge 9226366635 7 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Karuna M Nigavekar 9922808182 8 Raigarh Alibag Alibag (Urban) Tahasil Alibag Setu [email protected] 0 9 Raigarh Alibag Ambepur Shama Sanjay Dongare [email protected] 8087776107 10 Raigarh Alibag Ambepur Pranit Ramesh Patil 9823531575 11 Raigarh Alibag Awas Rohit Ashok Bhivande [email protected] 7798997398 12 Raigarh Alibag Bamangaon Rashmi Gajanan Patil [email protected] 9146992181 13 Raigarh Alibag Bamangaon NITESH VISHWANATH PATIL 9657260535 14 Raigarh Alibag Belkade Sanjeev Shrikant Kantak 9579327202 15 Raigarh Alibag Beloshi Santosh Namdev Nirgude [email protected] 8983604448 16 Raigarh Alibag BELOSHI KAILAS BALARAM ZAVARE 9272637673 17 Raigarh Alibag Chaul Sampada Sudhakar Pilankar [email protected] 9921552368 18 Raigarh Alibag Chaul VINANTI ANKUSH GHARAT 9011993519 19 Raigarh Alibag Chaul Santosh Nathuram Kaskar 9226375555 20 Raigarh Alibag Chendhre pritam umesh patil [email protected] 9665896465 21 Raigarh Alibag Chendhre Sudhir Krishnarao Babhulkar -

REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932'

EAST INDIA (CONSTITUTIONAL REFORMS) REPORT of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) "1932' Presented by the Secretary of State for India to Parliament by Command of His Majesty July, 1932 LONDON PRINTED AND PUBLISHED BY HIS MAJESTY’S STATIONERY OFFICE To be purchased directly from H^M. STATIONERY OFFICE at the following addresses Adastral House, Kingsway, London, W.C.2; 120, George Street, Edinburgh York Street, Manchester; i, St. Andrew’s Crescent, Cardiff 15, Donegall Square West, Belfast or through any Bookseller 1932 Price od. Net Cmd. 4103 A House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. The total cost of the Indian States Enquiry Committee (Financial) 4 is estimated to be a,bout £10,605. The cost of printing and publishing this Report is estimated by H.M. Stationery Ofdce at £310^ House of Commons Parliamentary Papers Online. Copyright (c) 2006 ProQuest Information and Learning Company. All rights reserved. TABLE OF CONTENTS. Page,. Paras. of Members .. viii Xietter to Frim& Mmister 1-2 Chapter I.—^Introduction 3-7 1-13 Field of Enquiry .. ,. 3 1-2 States visited, or with whom discussions were held .. 3-4 3-4 Memoranda received from States.. .. .. .. 4 5-6 Method of work adopted by Conunittee .. .. 5 7-9 Official publications utilised .. .. .. .. 5. 10 Questions raised outside Terms of Reference .. .. 6 11 Division of subject-matter of Report .., ,.. .. ^7 12 Statistic^information 7 13 Chapter n.—^Historical. Survey 8-15 14-32 The d3masties of India .. .. .. .. .. 8-9 14-20 Decay of the Moghul Empire and rise of the Mahrattas. -

Punj Lloyd Wins Contract for Dabhol - Panvel Pipeline Project (DPPL) from GAIL Order Valued at Rs 164.24 Crore

Punj Lloyd wins contract for Dabhol - Panvel Pipeline Project (DPPL) from GAIL Order Valued at Rs 164.24 crore New Delhi, July 4, 2006 Punj Lloyd Limited has been awarded the contract for Dabhol - Panvel Pipeline Project (DPPL) from GAIL. The value of the contract is Rs 164.24 crore on EPC basis. The scope of work broadly involves residual engineering, procurement, installation, testing and commissioning of Panvel-Dabhol 30 dia pipeline system from GAIL's station, installation at Panvel to Dabhol terminal including terminal work, temporary and permanent cathodic protection system, intermediate SV/IP/repeater/tap-off stations, crossings by Horizontal Directional Drilling (H.D.D) and all associated mechanical, civil, structural, electrical, instrumentation work and laying of optical fibre cable, HDPE duct, etc excluding supply of line pipe, which shall be supplied as free issue material by GAIL. Comprising two parts, the project involves the laying of the 30" dia pipeline in 113 km length from Panvel to upstream of Savitri river crossing in 2 spreads and a length of 74 km from upstream of Savitri river crossing to Dabhol terminal. This pipeline will pass through some of the steepest slopes in the country. Other facilities include a receipt cum despatch terminal at Dabhol, sectionalising valve stations and intermediate pigging station with a tap-off facility. fast track project, the scheduled time for completion is within 10 and half months from the date of contract, it is worth mentioning that PLL in the past had bagged part of the Dahej-Uran Pipeline Project from GAIL. About Punj Lloyd Punj Lloyd is amongst the largest engineering and construction companies in India providing integrated design, engineering, procurement, construction and project management services for energy and infrastructure sector projects with operations spread across many regions in the Middle East, Caspian, Asia Pacific, Africa and South Asia . -

M/S M/S Exotic Bites

+91-8048372558 M/s M/s Exotic Bites https://www.indiamart.com/m-s-m-s-exotic-bites/ Incepted in the year 2015, Exotic Bites is amongst the foremost names, indulged in Wholesaling and Trading an extensive range of Green Peas, Fresh Paneer and many more. About Us Incepted in the year 2015, Exotic Bites is amongst the foremost names, indulged in Wholesaling and Trading an extensive range of Green Peas, Fresh Paneer and many more. The offered products are widely employed by customers for various purposes. These products are processed under the rigorous leadership of highly proficient experts using the optimum grade ingredient and advanced technology. These products are extremely used in the market for their longer shelf life, purity and nominal prices. Furthermore, the presented products are available in many forms as per the exact necessities of customers. In order to provide excellent quality of products to patrons, we have hired skilled and experienced team. Our team ensures that the products are delivered to patrons in within given time frame keeping the quality. Moreover, we work under the direction of our mentor Mr. Keval Damani (Partner). Under his direction we have attained a well-known place of this area. He has always motivated us to provide the best quality products to our customers. We provide our products in following locations: Thane, airoli, sanpada, turbhe, vashi, koparkarine, panvel, gansoli, midc, juinagar,nerul, seawood darave, CBD belapur, kharghar, manasarovar, khandeshwar,kalva diva ,kopar,dombivali,thakurli, kalyan vithalwadi. ulhasnagar,ambernath, badlapur, vangani, shelu, neral bhivpuri rd, karjat palasdhari, khopoli ambivli,titwala, khadavli,..