2256AV-Inon Barnatan Digi Bklt.Qxd

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Francisco Tárrega (1852 – 1909

UNIVERSIDADE FEDERAL DO CEARÁ PRÓ-REITORIA DE PESQUISA E PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO FACULDADE DE EDUCAÇÃO PROGRAMA DE PÓS-GRADUAÇÃO CURSO DE DOUTORADO EM EDUCAÇÃO BRASILEIRA MARCO TULIO FERREIRA DA COSTA O VIOLÃO CLUBE DO CEARÁ HABITUS E FORMAÇÃO MUSICAL Fortaleza – CE 2010 MARCO TULIO FERREIRA DA COSTA O VIOLÃO CLUBE DO CEARÁ: HABITUS E FORMAÇÃO MUSICAL Tese de Doutorado submetida a defesa junto à Linha de Pesquisa: Educação, Currículo e Ensino / Eixo Temático Ensino de Música do Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação Brasileira da Universidade Federal do Ceará - UFC. Orientador: Professor Doutor Luiz Botelho Albuquerque Fortaleza – CE 2010 C874v Costa, Marco Túlio Ferreira da. O Violão Clube do Ceará: habitus e formação musical. / Marco Túlio Ferreira da Costa. – Fortaleza (CE), 2010. 131f. : il.; 31 cm. Tese (Doutorado) – Universidade Federal do Ceará, Faculdade de Educação, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação, Fortaleza (CE), 2010. Orientação: Prof. Dr. Luiz Botelho Albuquerque. 1- VIOLÃO - ESTUDO E ENSINO. 2 – VIOLÃO CLUBE DO CEARÁ - HISTÓRIA E CRÍTICA. 3- MÚSICA - ESTUDO E ENSINO – FORTALEZA (CE). 4- EDUCAÇÃO MUSICAL. 5- CULTURA E EDUCAÇÃO. 6 - ARTES - ESTUDO E ENSINO – FORTALEZA (CE). I - Albuquerque, Luiz Botelho (Orient). II - Universidade Federal do Ceará, Faculdade de Educação, Programa de Pós-Graduação em Educação. III – Título. CDD: 787.87 07 MARCO TÚLIO FERREIRA DA COSTA O VIOLÃO CLUBE DO CEARÁ HABITUS E FORMAÇÃO MUSICAL Área de Concentração: Ensino em Música APROVADO EM ____/_____/______ BANCA EXAMINADORA _________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Luiz Botelho Albuquerque (UFC) Presidente da Banca _________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Carlos Velásquez Rueda Examinador (UNIFOR) _________________________________________________________ Prof. Dr. Elvis de Azevedo Mattos Examinador (UFC) _________________________________________________________ Profa Dra Ana Maria Iório Dias Examinadora (UFC) _________________________________________________________ Prof. -

Mark Hilliard Wilson St

X ST. JAMES CATHEDRAL X SEATTLE X 9 APRIL 2021 X 6:30 PM X MUSICAL PRAYER mark hilliard wilson St. James Cathedral Guitarist Notes by Mark Hilliard Wilson Renewal and Redemption, Part 2 We are now at the one-year anniversary of the weekly Musical Prayer at Saint James Cathedral and I am so incredibly grateful for the opportunity to share my thoughts and music here at St. James. It’s been a very tough year in so many ways. Last year’s theme for the first musical prayer was “Renewal,” and tonight, I play an updated program with the added theme of redemption. More and more people are getting vaccinated which means we are getting closer and closer to a chance to actually meet in person. Longer days, occasionally even warm ones, and a sense of a more predictable course of action with our government feels like a collective lowering of the blood pressure. My program is a celebration of our ability to navigate hard times. It’s been a tough year and I’ve chosen music that reflects vehicles of renewal, whether found in prayer Oracion( de la Mañana), or nature (Wild Mountain Thyme), in reflection Charme( de la nuit), or even dance! (Thoor Ballylee, it’s like a jig, but is actually a celebration of the castle the poet Yeats lived in for a few years with his family). Oracion de la Mañana, Op. 39, No. 1 “Morning Prayer” Pyotr Tchaikovsky 1840–1893 transcribed by María Luisa Anido A prayer for tomorrow speaks for itself. Keep Praying! It seems like it's worked! Prelude No. -

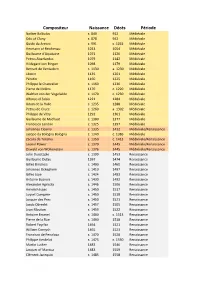

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus C

Compositeur Naissance Décès Période Notker Balbulus c. 840 912 Médiévale Odo of Cluny c. 878 942 Médiévale Guido da Arezzo c. 991 c. 1033 Médiévale Hermann of Reichenau 1013 1054 Médiévale Guillaume d'Aquitaine 1071 1126 Médiévale Petrus Abaelardus 1079 1142 Médiévale Hildegard von Bingen 1098 1179 Médiévale Bernart de Ventadorn c. 1130 a. 1230 Médiévale Léonin 1135 1201 Médiévale Pérotin 1160 1225 Médiévale Philippe le Chancelier c. 1160 1236 Médiévale Pierre de Molins 1170 c. 1220 Médiévale Walther von der Vogelwide c. 1170 c. 1230 Médiévale Alfonso el Sabio 1221 1284 Médiévale Adam de la Halle c. 1235 1288 Médiévale Petrus de Cruce c. 1260 a. 1302 Médiévale Philippe de Vitry 1291 1361 Médiévale Guillaume de Machaut c. 1300 1377 Médiévale Francesco Landini c. 1325 1397 Médiévale Johannes Ciconia c. 1335 1412 Médiévale/Renaissance Jacopo da Bologna Bologna c. 1340 c. 1386 Médiévale Zacara da Teramo c. 1350 c. 1413 Médiévale/Renaissance Leonel Power c. 1370 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance Oswald von Wolkenstein c. 1376 1445 Médiévale/Renaissance John Dunstaple c. 1390 1453 Renaissance Guillaume Dufay 1397 1474 Renaissance Gilles Binchois c. 1400 1460 Renaissance Johannes Ockeghem c. 1410 1497 Renaissance Gilles Joye c. 1424 1483 Renaissance Antoine Busnois c. 1430 1492 Renaissance Alexander Agricola c. 1446 1506 Renaissance Heinrich Isaac c. 1450 1517 Renaissance Loyset Compère c. 1450 1518 Renaissance Josquin des Prez c. 1450 1521 Renaissance Jacob Obrecht c. 1457 1505 Renaissance Jean Mouton c. 1459 1522 Renaissance Antoine Brumel c. 1460 c. 1513 Renaissance Pierre de la Rue c. 1460 1518 Renaissance Robert Fayrfax 1464 1521 Renaissance William Cornysh 1465 1523 Renaissance Francisco de Penalosa c. -

Fall Concert Calendar

FALL CONCERT CALENDAR September 2019 Tuesday, October 15 | 12:30 p.m. Liana Paniyeva, Piano Tuesday, September 3 | 12:30 p.m. • J.S. Bach-Busoni: Chaconne Duo SF • Amy Beach: Dreaming • Astor Piazzolla: Lo Que Vendra; Liber Tango • Clara Schumann: Scherzo, Op. 3 No. 2 • Redamés Gnattali: From Suite Retratos: Ernesto • Frédéric Chopin: Piano Sonata No. 3 Nazareth (Valse); Anacieto de Medeiros (Schottische) in B Minor, Op. 58 • Sergio Assad: Jobiniana No.1 • Phillip Houghton: Brolga Sunday, October 20 | 2:00 p.m. SF Mint • Lennon-McCartney: Fool on the Hill; Penny Lane; She’s Jack Cimo, Guitar Leaving Home; Eleanor Rigby • Francisco Tárrega: Capricho Árabe • Manuel de Falla: La Vida Breve (arr. Emilio Pujol) • Giulio Regondi: Nocturne Reverie, Op. 19 • Paulo Bellinati: Jongo • Mauro Giuliani: La Rose • Ísaac Álbeniz: El Polo from Suite Iberia; Asturias and Tuesday, September 10 | 12:30 p.m. Sevilla from Suite Española Temescal String Quartet • Leo Brouser arr. : Canción de Cuna Carl Blake, Piano • William Walton: Bagatelle No. 1 • Antonín Dvorak: Piano Quintet in A Major, Op. 81 • Frederico Bustamente: Misionera Sunday, September 15 | 2:00 p.m. SF Mint Tuesday, October 22 | 12:30 p.m. Trio Garufa Strobe • Angel Villoldo: El Choclo • Vincent Russo: Visions and Visitations • Enrique Saborido: Felicia • Alexis Alrich: Water Colors • Pedro Laurenz: Milonga de mis Amores • W. A. Mozart: Oboe Quartet, K. 370/368b, Rondeau • Aníbal Troilo: Romance de barrio; La trampera • Juan D’Arienzo: Paciencia Tuesday, October 29 12:30 p.m. • Astor Piazzolla: Oblivion Jeffrey LaDeur, Piano; Kindra Scharich, Mezzo Soprano • Juan Carlos Cobián: El Motivo Program TBD • Cachilo Díaz: La Humilde • Enrique Maciel: La pulpera de Santa Lucía • Juan de Dios Filiberto: Quejas de Bandoneón November 2019 • Gerardo Matos Rodríguez: La Cumparsita Tuesday, November 5 | 12:30 p.m. -

Counterpoint and Performance of Guitar Music – Historical and Contemporary Case Studies

Counterpoint and Performance of Guitar Music – Historical and Contemporary Case Studies Paul Ballam–Cross B.Mus (Performance), M.L.I.S A thesis submitted for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at The University of Queensland in 2019 School of Music Abstract This thesis examines how contemporary composers approach the guitar and counterpoint. An historical overview of the guitar is provided at the outset of the thesis, leading to detailed examination of contrapuntal technique in an extended twentieth-century work by Miklós Rózsa, and addresses effective guitar performance techniques in relation to different kinds of contrapuntal textures. These historical, technical and performance considerations then inform a series of interviews with six contemporary composers (Stephen Hough, Angelo Gilardino, Stephen Goss, Tilmann Hoppstock, Ross Edwards, and Richard Charlton). These interviews aim to provide insight into how 21st century composers approach contrapuntal writing for the guitar. The interviews are paired with detailed discussions of representative works for guitar by each composer. These discussions deal particularly with difficulties in practical performance and with how the composer has achieved their compositional goals. This thesis therefore seeks to discover how approaches to the guitar and counterpoint (including challenges, limitations and strategies) have changed and evolved throughout the instrument’s existence, up to some of the most recent works composed for it. i Declaration by author This thesis is composed of my original work, and contains no material previously published or written by another person except where due reference has been made in the text. I have clearly stated the contribution by others to jointly–authored works that I have included in my thesis. -

Download the Point Classics Catalogue

THOUSANDS OF HOURS OF GREAT CLASSICAL RECORDINGS ALL ROYALTY CLEARED FOR MASTER RIGHT PERFORMANCE AND PUBLISHING USAGE Point Classics is a wholly owned subsidiary Of One Media iP Group Plc. One Media iP Ltd, Pinewood Studios, 623 East Props, Pinewood Road, Iver Heath, Buckinghamshire, SL0 0NH, England. T: 44 (0) 1753 78 5500 E: [email protected] USA Contact: Mary Kuehn. E: [email protected] www.onemediaip.com www.pointclassics.com Calling all Advertisers, Agencies, Radio Productions, TV & Film Music Sync Supervisors, Gaming companies, Web Designers, Music Workshops, Schools, Universities, Live Event Organisers and Exhibitors. The problem with music is that you have to pay every time you use it. Imagine a classical music library at your fingertips that you simply rent annually; no extras, no hidden costs, just one annual fee and use and use and use. Thousands of the worlds best classical movements. Over 300 ready-made 30 second commercial edits, over 500 ready-made 5 second (best-of-the-best known bits) sound bites (‘stings’) all commercially prepared. All for one annual fee with no additional royalties. No public domain music. All music copyright and publishing cleared for worldwide use and registered at the Library of Congress. All recorded in stereo and supplied to you as WAV files for full broadcast quality. THE DEAL • Single annual Fee only. • 5 Second ‘Classical Stings’ edited and ready to use. • No Royalty charges. • Our library includes every genre of classical music for your film, TV, radio or audio project. • Music delivered on a hard drive/FTP for upload You’ll find the production music you need to your internal system for all team access. -

Ben Sullivan

Saturday, May 27, 2017 • 9:00 p.m Ben Sullivan Junior Recital DePaul Recital Hall 804 West Belden Avenue • Chicago Saturday, May 27, 2017 • 9:00 p.m. DePaul Recital Hall Ben Sullivan, classical guitar Junior Recital Diana Ortiz, violin PROGRAM Francisco Tárrega (1852 - 1909) El Columpio Edvard Grieg (1843 - 1907) Lyric Pieces Book III (1886), Op 43, No 2 Ensom vandrer (Lonely Wanderer) Fernando Sor (1778 - 1839) Estudio No 11, Op 6 (1815) Francisco Tárrega (1852 - 1909) Marieta Federico Moreno Torroba (1891 - 1982) Sonatina (1924) Astor Piazzolla (1921 - 1992) Histoire du Tango (1986) II. Cafe 1930 I. Bordel 1900 Ben Sullivan is from the studio of Mark Maxwell. This recital is presented in partial fulfillment of the degree Bachelor of Music. As a courtesy to those around you, please silence all cell phones and other electronic devices. Flash photography is not permitted. Thank you. Ben Sullivan • May 27, 2017 PROGRAM NOTES Fransicso Tárrega (1852-1909) El Columpio Duration: 4 minutes Tárrega was a Spanish born composer and often regarded as one of the greatest guitarists in history. Legend claims, that as a child he was thrown into an irrigation channel by his nanny for constantly wetting the bed. This caused a severe injury to his eyes. In fear of his eminent blindness, his father sent him to study at the Madrid Conservatory in Spain. Here, he would learn to make a living as a composer and performer. His professors of composition quickly told him to drop any idea of a career with the piano, and to focus all of his efforts on the guitar. -

Sábado 24 De Octubre 2020

*Programación sujeta a cambios sin previo aviso* SÁBADO 24 DE OCTUBRE 2020 12:00:00a 00:00 sábado, 24 de octubre de 2020 12A NO - Nocturno 12:00:00a 19:52 Suite de "Ludovicus Pius" (1726) Georg Caspar Schurmann (1672/73- Academ. de la Mus. Antigua, Berlín 12:19:52a 19:33 Concierto p/clarinete, viola y orq. op.88 en mi men. Max Bruch (1838-1920) Kent Nagano de la ópera de Lyon Paul Meyer-clarinete/Gérard Caussé-viola 12:39:25a 15:46 Ecos de una américa nuestra Mario Kuri-Aldana (1931-2013) Gordon Campbell Sinfónica de Aguascalientes 12:55:11a 00:50 Identificación estación 01:00:00a 00:00 sábado, 24 de octubre de 2020 1AM NO - Nocturno 01:00:00a 57:43 La vida breve Manuel De Falla (1876-1946) Eduardo Mata Sinfónica Simón Bolivar de Venezuela Marta Senn. mezzo-sop; Fernando de la Mora, tenor; Cecilia Angell, mezzo-sop. 01:57:43a 00:50 Identificación estación 02:00:00a 00:00 sábado, 24 de octubre de 2020 2AM NO - Nocturno 02:00:00a 15:31 Sonata p/ violín y bajo cont. "Dido abandonada" (B.g10) sol Giuseppe Tartini (1692-1770) (ver créditos) Fabio Biondi-violín; Rinaldo Alessandrini-clavecín; Maurizio Naddeo-cello; Pascal 02:15:31a 30:30 De Mi Vida (vers. orquestal de George Szell) Bedrich Smetana (1824-1884) Geoffrey Simon Sinfónica de Londres 02:46:01a 09:36 Relfexiones no.6 p/cello y guitarra (1986) Jaime Zenamon (1953-) Claremont Dúo Maxine Neuman, cello; Peter Ernst, guitarra 02:55:37a 00:50 Identificación estación 03:00:00a 00:00 sábado, 24 de octubre de 2020 3AM NO - Nocturno 03:00:00a 16:38 El verano, cantata Op.5 no.2 Joseph-Bodin de Boismortier (1689-1755) Ensamble Arion Hervé Lamy, tenor 03:16:38a 30:32 12 Estudios p/piano op.10 Frederic Chopin (1810-1849) Nikita Magaloff-piano 03:47:10a 08:41 Sonata en Si bem.p/ flauta y continuo Anónimo Horacio Franco Capella Cervantina Horacio Franco-flauta 03:55:51a 00:50 Identificación estación 04:00:00a 00:00 sábado, 24 de octubre de 2020 4AM NO - Nocturno 04:00:00a 08:12 Paisaje cubano con rumba (1985) p/4 guit. -

Pablo Sáinz Villegas

557596 bk Sainz US 28/06/2004 01:40pm Page 8 Laureate Series • Guitar Pablo Sáinz Villegas 2003 Winner: Certamen Internacional de Guitarra “Francisco Tárrega”, Benicásim Pablo Sáinz Villegas JOAQUÍN TURINA (1882-1949) JOAQUÍN RODRIGO (1901-1999) 1 Sevillana (Fantasia) 5:45 @ En los trigales 3:59 Hommage à Tárrega 4:51 # Invocación y danza 8:31 First Prize: 2 I Garrotin 2:39 (Homenaje a Manuel de Falla) 3 II Soleares 2:12 2003 Tárrega International MANUEL DE FALLA (1876 - 1946) FEDERICO MORENO TORROBA (1891-1982) $ Homenaje ‘Le tombeau de Claude Debussy’ 3:45 Guitar Competition, Sonata - Fantasía * 17:07 4 I Lento - Allegretto 10:01 5 II Allegretto 1:43 ROBERTO GERHARD (1896-1970) Benicásim 6 III Allegro 5:23 % Fantasia: Interlude in Cantares 4:39 from Castillos de España 5:42 7 Torija 3:33 ANDRÉS SEGOVIA (1893-1987) 8 Sigüenza 2:10 5 Anecdotas * 10:36 GUITAR RECITAL ^ IAllegretto 2:39 Suite castellana 8:29 & II Allegro moderato con grazia 1:06 9 I Fandanguillo 1:42 * III Lento malinconico 2:55 0 II Arada 4:07 ( IV Molto tranquillo 1:09 ! III Danza 2:40 ) V Allegretto vivo 2:46 FRANCISCO TÁRREGA (1852-1909) ¡ Maria - Gavota 1:28 FALLA • RODRIGO * World première recordings TURINA • TARREGA A MIS QUERIDOS PADRES PABLO Y MAITE POR TODO SU AMOR MORENO TORROBA SEGOVIA • GERHARD 8.557596 8 557596 bk Sainz US 28/06/2004 01:40pm Page 2 Nachahmung der phrygischen, der spanischsten aller Das letzte hier eingespielte Stück ist die Miniatur Pablo Sáinz - Guitar Recital Kirchentonarten; darüber hinaus macht er sich deren Maria – gavota von Francisco Tárrega (1852-1909), der Turina · Moreno Torroba · Rodrigo · Segovia · Falla · Gerhard · Tárrega bitonale Möglichkeiten zunutze. -

Recuerdos De La Alhambra Memories of the Alhambra Originally Composed for Classical Guitar

Recuerdos de la Alhambra Memories of the Alhambra originally composed for classical guitar The music, “Memories of the Alhambra,” reflects on a magnificent castle overlooking the city of Granada in southern Spain. Built during the 12th and 13th centuries while Spain was under Moorish dominion, the Alhambra is a picturesque and exceptional manifestation of Arabic and Islamic culture that prevailed in Spain for nearly eight centuries (711-1492). Here is a beautiful and effective piano setting of this familiar composition for classical guitar by Francisco Tárrega born November 29, 1852 at Vilareal in Spain. He began guitar studies at age eight and later studied piano and theory. He was one of the great guitar virtuosos and teachers of the 19th Century and was professor of guitar at the conservatory of Madrid and later at Barcelona. He died December 15, 1909. q = 88 Francisco Tárrega (1852-1909) Piano arrangement— Franklin Eddings Expressively and unhurried with some freedom 3 ? = > 4 l & ˙ œ l _˙ œ l ˙ . l ˙ œ l l p _œ l l _œ _œ l _œ _œ l 3 œ œ œ œ l 4 œ ˙ . œ œ œ l œ ˙ . œ œ œ l œ ˙ . œ œ œ l œ ˙ . œ œ l l ? l l l l with pedal 5 ? l & ˙ œ l ˙ œ l ˙ . l ˙ . l l _œ _œ l _œ _œ l _œ _œ l cresc. _œ _œ l l œ ˙ . œ œ œ l œ ˙ . œ œ œ l œ ˙ . œ œ œ l œ ˙ . œ œ œ l l ? l l l &l £ 9 A ˙ œ œ œ l & l ˙ l œ œ œ # ˙ . -

Francisco Tárrega and the Art of Guitar Transcription

Francisco Tárrega and the Art of Guitar Transcription Walter Aaron Clark University of California, Riverside The year 2009 is momentous for many reasons, among them the death centenaries of two giants of Spanish music: Isaac Albéniz (1860-1909) and Francisco Tárrega (1852- 1909). Both were virtuoso soloists as well as accomplished composers, and this tells us much about the age in which they lived, one in which soloists were expected to be more than mere executants. They were also expected to be able to improvise and to compose their own music. However, the pianist Albéniz inherited an ample and first-rate repertoire; the guitarist Tárrega did not. Tárrega’s output, then, includes not only original compositions but also many transcriptions of works by famous composers of the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries. To be sure, he was not the first guitarist in history to transcribe works from other media to his own. This had been going on since the sixteenth century. But he did so more extensively and influentially than any of his predecessors, and he thus established a practice continued by virtually every guitarist since his time. Indeed, though it is no longer incumbent on classical guitarists to compose and perform their own music, and has not been customary for many decades, they are expected to have made their own original arrangements and transcriptions of music other than that for the guitar. This is a direct result of Tárrega’s influence, and though the practice is not without its critics and controversy, there is none the less an art to doing this sort of thing, an art we will now explore. -

IGRC Conference 18Th - 23Rd March 2016

IGRC Conference 18th - 23rd March 2016 Abstracts and Biographies SATURDAY 19th MARCH 2016 Session 1 – 9.00 am to 10.30 am Papers in TB18 Benjamin Bruant (IGRC, University of Surrey) Andrès Segovia’s collaboration with Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco (MCT): Case study - Passacaglia opus 180 The Passacaglia, opus 180, was composed by Mario Castelnuovo-Tedesco in 1956 and is dedicated to Andrès Segovia, who never played or recorded it. The score was published in 1970 by Berben, a publishing house which had never previously worked with Andrès Segovia. The score was revised and fingered in 1968 by the guitarist and musicologist Angelo Gilardino. We can therefore question if Segovia had any influence on the piece, during the compositional, editing or publication process. When the immediate answer would seem to be that Segovia’s influence on the piece is limited or even non-existent, the newly discovered correspondences between the composer and the guitarist refute this hypothesis. This case study, based on analysis of the manuscript score as well as study of the correspondences between Segovia and MCT, aims to define the role of Segovia in the compositional process, to question the value of the publication of the Passacaglia and to assess the importance of historical information contained in the MCT/Segovia correspondences. Born in Le Havre (France), Benjamin Bruant began his musical study at the age of seven in his hometown. After getting a bachelor degree in Physics, he moved to Paris in order to improve his music knowledge. He studied with Pedro Ibanez at the Conservatoire Nationale de Region of Paris for three years.