The Salonican Brothers Constantine and Methodius and Their Role in Development of the European Christian Universe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Historical Developments

Chapter 3: Historical Developments 3.1 LINGUISTic HISTORY OF HALOZE The Slovene dialect area of Haloze, which is located to the southeast of Ptuj along the present Slovene‑Croatian national border, is essentially part of the Pannonian Slovene dialect base (See map 3 below.), yet my own fieldwork in the area documents an unexpected phonological development in Haloze that connects it to an ancient Kajkavian Croatian vocalic merger (Lundberg 1999). Map 3: Dialect Map of Slovenia HUNGARY AUSTRIA G A Maribor F E ITALY A Koroška B Primorska Ljubljana C C Rovtarska B D Dolenjska E Gorenjska D F Štajerska G Panonska Croatia This chapter will provide an explanation for this unusual occurrence us‑ ing a synthesis of available historical data and dialect information. This 49 Grant H. Lundberg, Dialect Leveling in Haloze, Slovenia analysis will also provide insights on the historical development of the ethnic, linguistic and political border between Slovenia and Croatia as well as comment on the complexity of deciphering dialect data on and around national borders, where dialect material and ideological concerns are often intertwined.16 3.2 HISTORicAL PERSPECTIVE Most Slavists agree that the Slavs who would much later be known as the Czechs, Slovaks, Slovenes and Croatians entered the Pannonian plain and the alpine region just north of the Adriatic in the mid sixth century. They may have arrived in the Carpathian basin with some preexisting dialect divisions (See Ramovš 1933 and Andersen 1999.), but little is known about early linguistic distinctions among the Western South Slavs. It is true that the earliest kingdoms among these Slavs united parts of the Alpine and Pan‑ nonian regions.17 Samo’s seventh‑century kingdom united Bohemian and Alpine Slavs (Kos 1955: 77), and the ninth‑century Pannonian kingdoms of Pribina, Kocel and Greater Moravia also included these groups (Kos 1955: 116, Guldescu 98). -

HISTORY of SLOVAKIA Small State with Rich History Samova Ríša- Samo‘S Empire

HISTORY OF SLOVAKIA Small state with rich history Samova ríša- Samo‘s empire • Ancestors of Slovaks were Slavs. Their homeland was between the rivers Visla and Dneper, north of the mountains Karpaty. In 5th and 6th century they moved to another place. Some of them stayed on our territory.They nurtured the peasantry, beekeeping, handicrafts. • In 6th century Avars (nomadic tribes from Asia) came and they settled on the territory of today's Hungary. From there, they were attacking the neighbouring Slavonic nations. Slavs united in the 7th century to defend themselves against aggressive Avars. - in the fight Frankish merchant Samo helped them and with his help they won - Slavonic tribes created a tribal union- Samo‘s empire - it existed in years 623-658 Veľká Morava-Great Moravia • NITRA PRINCIPALITY - Slavs slowly started to build strong forts (Bojná, Pobedim) - the most important fort was in Nitra, it was the seat of the prince - first known prince was Pribina - in the west, there was Moravian principality, with the seat in Mikulčice, prince Mojmír ruled there - year 833- Mojmír I. expelled Pribina and occupied Nitra principality - by the combination of the two principalities Great Moravia originated • GREAT MORAVIA - GM resulted in conflicts with the Frankish Empire, Franks wanted to control GM - Mojmír I. didn‘t want to subordinate to Franks, so they deprived him of power and he was replaced by Rastislav. He invited Thessalonian brothers- Konštantín and Metod - Svätopluk betrayed Rastislav and issued him to Franks - when Svätopluk died, -

The Cyril and Methodius Mission and Europe

THE CYRIL AND METHODIUS MISSION AND EUROPE 1150 Years Since the Arrival of the Thessaloniki Brothers in Great Moravia Pavel Kouřil et al. The Institute of Archaeology of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Brno THE CYRIL AND METHODIUS MISSION AND EUROPE – 1150 Years Since the Arrival of the Thessaloniki Brothers in Great Moravia Pavel Kouřil et al. The Institute of Archaeology of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Brno Brno 2014 THE CYRIL AND METHODIUS MISSION AND EUROPE – 1150 Years Since the Arrival of the Thessaloniki Brothers in Great Moravia Pavel Kouřil et al. The publication is funded from the Ministry of Culture NAKI project „Great Moravia and 1150 years of Christianity in Central Europe“, for 2012–2015, ID Code DF12P01OVV010, sponsored as well by the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic. The Cyril and Methodius Mission and Europe – 1150 Years Since the Arrival of the Thessaloniki Brothers in Great Moravia Head of the team of authors: doc. PhDr. Pavel Kouřil, CSc. Authors: Maddalena Betti, Ph.D., prof. Ivan Biliarsky, DrSc., PhDr. Ivana Boháčová, Ph.D., PhDr. František Čajka, Ph.D., Mgr. Václav Čermák, Ph.D., PhDr. Eva Doležalová, Ph.D., doc. PhDr. Luděk Galuška, CSc., PhDr. Milan Hanuliak, DrSc., prof. PhDr. Michaela Soleiman pour Hashemi, CSc., prof. PhDr. Martin Homza, Ph.D., prof. PhDr. Petr Charvát, DrSc., prof. Sergej A. Ivanov, prof. Mgr. Libor Jan, Ph.D., prof. Dr. hab. Krzysztof Jaworski, assoc. prof. Marija A. Jovčeva, Mgr. David Kalhous, Ph.D., doc. Mgr. Antonín Kalous, M.A., Ph.D., PhDr. Blanka Kavánová, CSc., prom. -

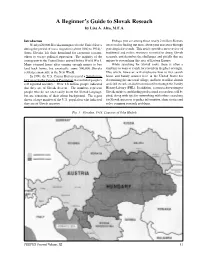

A Beginner's Guide to Slovak Reseach

A Beginner’s Guide to Slovak Reseach by Lisa A. Alzo, M.F.A. Introduction Perhaps you are among those nearly 2 million Slovaks Nearly 620,000 Slovaks immigrated to the United States interested in finding out more about your ancestors through during the period of mass migration (about 1880 to 1914).1 genealogical research. This article provides an overview of Some Slovaks left their homeland for economic reasons, traditional and online resources essential to doing Slovak others to escape political repression. The majority of the research, and describes the challenges and pitfalls that are immigrants to the United States arrived before World War I. unique to researching this area of Eastern Europe. Many returned home after earning enough money to buy While searching for Slovak roots, there is often a land back home, but eventually some 500,000 Slovaks tendency to want to search for records in the place of origin. settled permanently in the New World. This article, however, will emphasize how to first search In 1990, the U.S. Census Bureau issued a Supplemen- home and family sources here in the United States for tary report to the Census of Population that included people’s determining the ancestral village, and how to utilize church self-reported ancestry.2 Over 1.8 million people indicated and civil records available on microfilm through the Family that they are of Slovak descent. The numbers represent History Library (FHL). In addition, resources for writing to people who do not necessarily know the Slovak language, Slovak archives and finding professional researchers will be but are conscious of their ethnic background. -

Mission of Saints Cyril and Methodius and Their Contacts with Kocel, Duke of Pannonia

European Journal of Science and Theology, December 2016, Vol.12, No.6, 233-243 _______________________________________________________________________ MISSION OF SAINTS CYRIL AND METHODIUS AND THEIR CONTACTS WITH KOCEL, DUKE OF PANNONIA Martin Hetényi* Constantine the Philosopher University in Nitra, Faculty of Arts, Štefánikova 67, 949 74 Nitra, Slovak Republic (Received 8 July 2016) Abstract The main topic field of this study is a scientific view of the little-known destinies of the Pannonian duke Kocel, the son of Pribina from Nitra. Author more closely presents a summary of political, military and religious relations that were developed in the area of a far-reaching foreign and domestic politics of Kocel from the beginning of his reign until the peak of his power. In the late 60‟s of the 9th century, his court became an important centre of mission of Saints Cyril and Methodius, as evidenced by written and archaeological sources. The attractiveness of topic mainly consists in boosting of professional discussion in recent years. Keywords: mission, Saints Cyril and Methodius, duke Kocel, Christianization, Pannonia 1. Introduction Cultural and spiritual dimension of the Saints Cyril and Methodius mission is currently getting a deserved attention in many countries [1]. The mission in Great Moravia in 863 did not arise at random. As it is known, one of the main reasons of their arrival in the territory of Great Moravia was an effort of the Moravian duke Rastislav to extricate from political or Church-political dependence of Frankish Empire, a neighbouring great power. From the second half of the 8th century, two principalities were formed in the territory of today‟s Slovakia and Moravia – Moravian Principality and Nitra Principality [2]. -

History of Slovakia

History of Slovakia Obchodná akadémia, Veľká okružná 32, 011 57 Žilina Prehistory Slovakia's territory had been inhabited in the Palaeolithic - Nové Mesto nad Váhom, Bojnice and Gánovce. The best known artifact is the Venus of Moravany from Moravany nad Váhom. Neolithic habitation was found in Želiezovce, Gemer, the Domica cave and at Nitriansky Hrádok. 2 History of Slovakia Prehistory Bronze Age was marked by the Čakany andVelatice cultures, followed by the Calenderberg culture and the Hallstatt culture.The major Celtic tribes living in Slovakia were Cotini and Boii. The great invasions of the 4–8th centuries saw the emergence of the Huns, followed by the expansion of the Ostrogoths, Lombards, Gepids, Heruli. Eurasian Avars followed, battling the Byzantine Empire, to be replaced by the Slavs. 3 History of Slovakia The Slavs Parts of the Slavic population that settled in the Middle Danube area were unified by King Samo,after a successful Slavic insurrection against the Avar Khaganate in 623. In 631, Samo defeated the Frankish army of King Dagobert at the Battle of Wogastisburg. Samo's Empire, the first known political formation of Slavs, disappeared after the death of its founder in 665 and its territory was again included into Avar Khaganate. Around 828, Archbishop Adalram of Salzburg consecrated a church for Prince Pribina in Nitrava. In 833, Mojmír I, Duke of the Moravians, expelled Pribina. 4 History of Slovakia The era of Great Moravia Great Moravia arose around 830 when Mojmír I unified the Slavic tribes settled north of the Danube and extended the Moravian supremacy over them. -

Neglected and Under-Utilized Species Research in 21 Century

6th International Conference of the European Amaranth Association Neglected and Under-utilized Species Research in 21st Century Book of Abstracts October 21 - 24, 2012, Nitra, Slovak Republic ISBN 978-80-970662-1-5 Editors Gabriela Libiaková, Alena Gajdošová, Andrea Hricová Institute of Plant Genetics and Biotechnology SAS, Nitra, Slovak Republic The abstracts have been printed as received, no proofreading have been made. The contents of abstracts are entirely the responsibility of the authors. CONTENT Neglected and under-utilized crops for sustainable food production S. Mohan JAIN 5 Enzyme polymorphism analysis in irradiated amaranth (Amaranthus spp.) lines Monika KEČKEŠOVÁ, Pavol MÚDRY, Andrea HRICOVÁ, Zdenka GÁLOVÁ 6 Progress in sequencing Amaranthus tricolor and chloroplast genome phylogenetics Erika VILJOEN, D.A. ODENY, D.J.G. REES 9 Genetic analysis of Amaranthus hypochondriacus L. genotypes using Inter- Simple Sequence Repeats Veronika ŠTEFÚNOVÁ, Milan BEŽO, Slavomíra SENKOVÁ, Mária LABAJOVÁ 11 Adding value to amaranth through the use of radiation mutagenesis Andrea HRICOVÁ, Jozef FEJÉR, Gabriela LIBIAKOVÁ, Alena GAJDOŠOVÁ 15 Effect of selenium supplementation on the biological activity of amaranth sprouts Paweł PAŚKO, Małgorzata TYSZKA–CZOCHARA, Ewelina GAJDZIK, Renata WIETECHA-POSŁUSZNY, Paweł ZAGRODZKI 16 In vitro cultivated explant type influence on the expression of totipotency in different varieties of Amaranthus sp. Silvana DANAILA GUIDEA, Narcisa BABEANU, Ovidiu POPA, Ioana POPA, Denisa STANCIU 19 Field evaluation of genetic -

The Great Moravian Territory of Nitra. Cultural Manifestations, Territorial Scope and the Ethnic and Social-Political Identity of Its Population

The Great Moravian territory of Nitra. Cultural manifestations, territorial scope and the ethnic and social-political identity of its population Tomáš König Mgr. Tomáš König, PhD. Comenius University in Bratislava Faculty of Arts Department of Archaeology Gondova 2 814 99 Bratislava Slovakia e-mail: [email protected] Muzeológia a kultúrne dedičstvo, 2017, 5:2:9-28 The Great Moravian territory of Nitra. Cultural manifestations, territorial scope and the ethnic and social- political identity of its population The main objective of the article is to determine the territorial scope of the Great Moravian territory of Nitra based on an analysis of archaeological sources. Specific cultural manifestations identified in the focal area of the Danube lowland delimit the studied territory from the settlement of adjacent regions of Slovakia and from the central settled territory in the Morava River basin. An interpretation of the results, supported by a comparison with written sources and linguistic data a new view of the social-political identity of the Nitra population. Key words: Great Moravia, territory of Nitra, inhumation rite, Christianisation, social-political identity The territory of Nitra as a distinct administrative unit of the Great Moravian Empire is a widely accepted historical phenomenon. Based primarily on information from written sources, it has become the subject of further research. Although the development of archaeological research over the past century produced a relatively large number of new sources, they have not been widely utilised thus far to address basic questions such as the territorial scope, the particularities of cultural manifestations or the ethnic and social-political identity of its population. -

War and Peace: Historiography and Seventhcentury Embassies

War and peace: historiography and seventh- century embassies PAUL S. BARNWELL The evidence for, and circumstances of, seventh-century embassies are examined, and it is suggested that the lack of documented diplomacy is partly accounted for by what may have been relatively peaceful condi- tions in the west, and partly by the nature of the sources for the period. Before the Renaissance, when ambassadors and consuls of one state began to be permanently based in the territory of another," communi- cation with foreign rulers was conducted by means of legates sent between kings for speci¢c purposes. The objects of such contact were many and varied, including the resolution of disputes (before or after armed con£ict arose); making alliances and seeking aid against third parties; the negotiation of rights for traders and other wayfarers, including the giving of assurances concerning the intentions of o¤cial travellers. There may also have been an element of information gathering ^ or spying ^ on at least some occasions, while at other times the purpose of contact may have been no more speci¢c than opening and maintaining lines of communication in the hope of procuring good relations in case of future requests for assistance, and of avoiding the kind of mutual suspicion which often results from lack of dialogue.á It is generally recognised amongst those who have written about early medieval diplomacy that the majority of the evidence for diplomacy in the sixth- and seventh-century west relates to the period before the middle of the seventh century, and particularly to the sixth. -

Routes4u Feasibility Study on the Cyril and Methodius Route in the Danube Region

Routes4U Feasibility Study on the Cyril and Methodius Route in the Danube Region Routes4U Project Routes4U Feasibility study on the Cyril and Methodius Route in the Danube Region ROUTES4U FEASIBILITY STUDY ON THE CYRIL AND METHODIUS ROUTE IN THE DANUBE REGION June 2020 The present study has been developed in the framework of Routes4U, the joint programme between the Council of Europe and the European Commission (DG REGIO). Routes4U aims to foster regional development through the Cultural Routes of the Council of Europe programme in the four EU macro-regions: the Adriatic and Ionian, Alpine, Baltic Sea and Danube Regions. A special thank you goes to the author Dr. Slavia Barlieva, Bulgarian Academy of Sciences, and to the numerous partners and stakeholders who supported the study. The opinions expressed in this work are the responsibility of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy of the Council of Europe. Cover Photos: European Commission, Wikimedia Commons [CC BY-SA 3.0], UNESCO Silvan Rehfeld 2 | 76 www.coe.int/routes4u Routes4U Feasibility study on the Cyril and Methodius Route in the Danube Region CYRIL AND METHODIUS ROUTE IN THE DANUBE REGION Content Executive summary .......................................................................................................... 4 Methodology ................................................................................................................... 4 HISTORICAL BACKGROUND ....................................................................................... -

“Unconquered Louis Rejoiced in Iron”: Military History in East Francia Under King Louis the German (C. 825-876) a Dissertat

“Unconquered Louis Rejoiced In Iron”: Military History in East Francia under King Louis the German (c. 825-876) A Dissertation Submitted to the Faculty of the University of Minnesota By Christopher Patrick Flynn In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy Advised by Dr. Bernard S. Bachrach May 2020 Copyright © 2020 Christopher P. Flynn All Rights Reserved i ACKNOWLEDGMENTS I have accrued huge debts in the creation of this work, which will not be adequately repaid by mention here. I must thank the faculty of the University of Minnesota, particularly the Department of History and the Department of Classical and Near Eastern Studies. Thanks are especially due to my committee members, Drs. Bernard Bachrach, Kathryn Reyerson, Andrew Gallia, Michael Lower, and Oliver Nicholson, as well as to Drs. Howard Louthan and Gary Cohen, both of whom served as Director of the Center for Austrian Studies during my tenure there. I thank the office staff of the history department for navigating endless paperwork on my behalf, as well as the University of Minnesota library system for acquiring copies of difficult to find works and sources in several languages. Especially, among these numerous contributors, I thank my adviser Dr. Bachrach, whose work was the reason I came to Minnesota in the first place, and whose support and erudition made the journey worth it. In this regard, I thank Dr. Lorraine Attreed of the College of the Holy Cross, who not only introduced me to the deeply fascinating world of early medieval Europe, but also exposed me to the work of Dr. -

The Historical Background of the Church Conflict in Great Moravia*

The Historical Background of the Church Conflict in Great Moravia* ZDENÈK R. DITTRICH The short but eventful and quite tragic history of the former Slavic church province on the Danube begun with the Christianization of the Slavic people of that region. Therefore, it is desirable to deal first with the question under which circumstances, when, and by whom this religious — and, in a broader sense — sociocultural adaptation-process of the origi- nally purely pagan people was induced. One must start with the fact that the general conditions of Christianization were not always the same. The Slavic immigrants who had settled the former Roman provinces, Noricum and Pannonia, in the course of their migration had more oppor- tunities to absorb the less diffuse elements of the Christian religion, mentality, and way of life than the Slavs living outside the Danube basin. Nevertheless, at least as far as Great Moravia was concerned, there was only a difference in extent. From recent excavations in the neighborhood of the Moravian Stare Mesto and elsewhere, one can draw the conclusion that the Roman influence north of the Danube, as well as subsequent cultural and commercial relationships of this region with the Mediter- ranean-Adriatic area, were quite extensive, much stronger than had been considered possible by previous research.1 The fact that contact with the Christian Romanic or Romanized population of the Danube province and Christendom south of the Alps had an effect also on religious matters can be seen from the fact that the Christian terminology of West and South Slavic languages contains a number of words borrowed from Romance languages which had ap- parently already been taken over at the beginning of the cultural con- frontation.