Western Australia's Journal of Systematic

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Traditional Information and Antibacterial Activity of Four Bulbine Species (Wolf)

African Journal of Biotechnology Vol. 10 (2), pp. 220-224, 10 January, 2011 Available online at http://www.academicjournals.org/AJB DOI: 10.5897/AJB10.1435 ISSN 1684–5315 © 2011 Academic Journals Full Length Research Paper Traditional information and antibacterial activity of four Bulbine species (Wolf) R. M. Coopoosamy Department of Nature Conservation, Mangosuthu University of Technology, P O Box 12363, Jacobs4026, Durban, KwaZulu-Natal, South Africa. E-mail: [email protected]. Tel: +27 82 200 3342. Fax: +27 31 907 7665. Accepted 7 December, 2010 Ethnobotanical survey of Bulbine Wolf, (Asphodelaceae) used for various treatment, such as, diarrhea, burns, rashes, blisters and insect bites, was carried out in the Eastern Cape Province of South Africa. Information on the parts used and the methods of preparation was collected through questionnaire which was administered to the herbalists, traditional healers and rural dwellers which indicated the extensive use of Bulbine species. Most uses of Bulbine species closely resemble that of Aloe . Dried leaf bases and leaf sap are the commonest parts of the plants used. Preparations were in the form of decoctions and infusions. Bulbine frutescens was the most frequently and commonly used of the species collected for the treatment of diarrhoea, burns, rashes, blisters, insect bites, cracked lips and mouth ulcers. The leaf, root and rhizome extracts of B. frutescens, Bulbine natalensis, Bulbine latifolia and Bulbine narcissifolia were screened for antibacterial activities to verify their use by traditional healers. Key words: Herbal medicine, diarrhea, medicinal plants, Bulbine species, antibacterial activity. INTRODUCTION Many traditionally used plants are currently being investi- developing countries where traditional medicine plays a gated for various medicinal ailments such as treatment to major role in health care (Farnsworth, 1994; Srivastava et cure stomach aliments, bolding, headaches and many al., 1996). -

Antimicrobial and Chemical Analyses of Selected Bulbine Species

./ /' ANTIMICROBIAL AND CHEMICAL ANALYSES OF SELECTED BULBINE SPECIES BY f' CHUNDERIKA MOCKTAR Submitted in part fulfilment ofthe requirements for the degree of Master of Medical Science (Pharmaceutical Microbiolgy) i,n the Department of Pharmacy in the Faculty of Health Sciences at the Universi1y of Durban-Westville Promotor: Dr S.Y. Essack Co-promotors: Prof. B.C. Rogers Prof. C.M. Dangor .., To my children, Dipika, Jivesh and Samika Page ii sse "" For Shri Vishnu for the guidance and blessings Page iji CONTENTS PAGE Summary IV Acknowledgements VI List ofFigures vu List ofTables X CHAPTER ONE: INTRODUCTION AND LITERATURE REVIEW 1 1.1 Introduction 3 1.1.1 Background and motivation for the study 3 1.1.2 Aims 6 1.2 Literature Review 6 1.2.1 Bacteriology 7 1.2.1.1 Size and shape ofbacteria 7 1.2.1.2 Structure ofBacteria 7 1.2.1.3 The Bacterial Cell Wall 8 1.2.2 Mycology 10 1.2.3 Traditional Medicine in South Africa 12 1.2.3.1 Traditional healers and reasons for consultation 12 1.2.3.2 The integration oftraditional healing systems with western Medicine 13 1.2.3.3 Advantages and Disadvantages ofconsulting traditional healers 14 1.2.4 Useful Medicinal Plants 16 1.2.5 Adverse effects ofplants used medicinally 17 1.2.6 The Bulbine species 19 1.2.6.1 The Asphodelaceae 19 1.2.6.2 Botany ofthe Bulbine species 19 CHAPTER TWO: MATERIALS AND METHODS 27 2.1 Preparation ofthe crude extracts 29 2.1.1 Collection ofthe plant material 30 2.1.2 Organic Extraction 30 2.1.3 Aqueous Extraction 31 2.2 Antibacterial Activities 31 2.2.1 Bacteriology 31 2.2.2 Preparation ofthe Bacterial Cultures 33 2.2.3 Preparation ofthe Agar Plates 33 2.2.4 Preparation ofCrude Extracts 33 2.2.5 Disk Diffusion Method 34 2.2.6 Bore Well Method 34 2.3 Mycology 34 2.3.1 Fungi used in this study 34 2.3.2 Preparation ofFungal Spores 35 2.3.3 Preparation ofC. -

Caesia Parviflora

Plants of South Eastern New South Wales Flower and seed case (var. parviflora). Australian Flowering stem (var. parviflora). Photographer Don Plant Image Index, photographer Murray Fagg, Ben Wood, Porters Gap Lookout, NW of Milton Boyd National park near Eden Flowering plant (var. minor). Photographer Russell Flowering stem with flower and spent flower (var. Best, Grampians National Park, Vic vittata). Australian Plant Image Index, photographer Paul Hadobas, north of Braidwood Common name Pale grass-lily. (Var. minor) Small Pale Grass-lily Family Hemerocallidaceae Where found Forest, woodland, heath, grassland, and damp places. var. minor: Kanangra Boyd National Park. Old records elsewhere. var. parviflora: Coast, ranges, and the eastern edge of the tablelands. var. vittata: Coast, ranges, and tablelands. Notes Perennial tufted herb to 0.75 m high with a branched rhizome. Hairless. Leaves basal, to 40 cm long, 1–8 mm wide, linear, with a more or less papery sheath at the base. Flowers with 6 'petals' each 3–8.5 mm long, greenish white to pink or blue, or mauve or purple. Flowers in clusters of 1–6. Family Anthericaceae in PlantNET. Family Asphodelaceae in VICFLORA. var. minor: Plant usually much less than 0.2 m high. Leaves to about 2 mm wide. Flowers mainly white or greenish white, also blue or purple, 'petals' less than 5 mm long. Flowers in many-branched clusters, the branches widely divergent, horizontal or spreading and turning up at the tips. Endangered NSW. Provisions of the NSW Biodiversity Conservation Act 2016 No 63 relating to the protection of protected plants generally also apply to plants that are a threatened species. -

National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972.PDF

Version: 1.7.2015 South Australia National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972 An Act to provide for the establishment and management of reserves for public benefit and enjoyment; to provide for the conservation of wildlife in a natural environment; and for other purposes. Contents Part 1—Preliminary 1 Short title 5 Interpretation Part 2—Administration Division 1—General administrative powers 6 Constitution of Minister as a corporation sole 9 Power of acquisition 10 Research and investigations 11 Wildlife Conservation Fund 12 Delegation 13 Information to be included in annual report 14 Minister not to administer this Act Division 2—The Parks and Wilderness Council 15 Establishment and membership of Council 16 Terms and conditions of membership 17 Remuneration 18 Vacancies or defects in appointment of members 19 Direction and control of Minister 19A Proceedings of Council 19B Conflict of interest under Public Sector (Honesty and Accountability) Act 19C Functions of Council 19D Annual report Division 3—Appointment and powers of wardens 20 Appointment of wardens 21 Assistance to warden 22 Powers of wardens 23 Forfeiture 24 Hindering of wardens etc 24A Offences by wardens etc 25 Power of arrest 26 False representation [3.7.2015] This version is not published under the Legislation Revision and Publication Act 2002 1 National Parks and Wildlife Act 1972—1.7.2015 Contents Part 3—Reserves and sanctuaries Division 1—National parks 27 Constitution of national parks by statute 28 Constitution of national parks by proclamation 28A Certain co-managed national -

Ultrastructural Micromorphology of Bulbine Abyssinica A

Pak. J. Bot., 47(5): 1929-1935, 2015. ULTRASTRUCTURAL MICROMORPHOLOGY OF BULBINE ABYSSINICA A. RICH. GROWING IN THE EASTERN CAPE PROVINCE, SOUTH AFRICA CROMWELL MWITI KIBITI AND ANTHONY JIDE AFOLAYAN* Medicinal Plants and Economic Development Research Centre (MPED), Department of Botany, University of Fort Hare, Alice, 5700, South Africa Corresponding author e-mail: [email protected]; Phone: +27 82 202 2167; Fax: +27 866 282 295 Abstract The genus Bulbine (Asphodelaceae) comprises about 40 species in South Africa. Bulbine abyssinica is a succulent member of the genus that occurs from the Eastern Cape, through Swaziland, Lesotho, and further north to Ethiopia. The species is often used in traditional medicine to treat rheumatism dysentery, bilharzia and diabetes. Inspite of its ethno medicinal value, not much data concerning the micro-morphological features is available in literature. The present study was undertaken to examine the ultra-morphological features of the leaf, stem and root of the plant using light and scanning electron microscopes and the elemental composition. The elemental compositions of the plant parts were done using energy dispersive x- ray spectroscopy. The mean length and width of the guard cells in the abaxial surface are 0.15 ± 0.002 mm and 0.14 ± 0.002 mm, respectively while those of the adaxial surface are 0.14 ± 0.001 mm and 0.12 ± 0.001 mm, respectively. The electron microscopy revealed the presence of crystals in the leaves, stems and roots. The EDXS microanalysis of the crystals revealed the presence of sodium, silicon, potassium and calcium as the major constituents. The leaf also showed the presence of iron and magnesium, while the stem had aluminium, phosphorous and magnesium. -

Tracing History

Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 911 Tracing History Phylogenetic, Taxonomic, and Biogeographic Research in the Colchicum Family BY ANNIKA VINNERSTEN ACTA UNIVERSITATIS UPSALIENSIS UPPSALA 2003 Dissertation presented at Uppsala University to be publicly examined in Lindahlsalen, EBC, Uppsala, Friday, December 12, 2003 at 10:00 for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy. The examination will be conducted in English. Abstract Vinnersten, A. 2003. Tracing History. Phylogenetic, Taxonomic and Biogeographic Research in the Colchicum Family. Acta Universitatis Upsaliensis. Comprehensive Summaries of Uppsala Dissertations from the Faculty of Science and Technology 911. 33 pp. Uppsala. ISBN 91-554-5814-9 This thesis concerns the history and the intrafamilial delimitations of the plant family Colchicaceae. A phylogeny of 73 taxa representing all genera of Colchicaceae, except the monotypic Kuntheria, is presented. The molecular analysis based on three plastid regions—the rps16 intron, the atpB- rbcL intergenic spacer, and the trnL-F region—reveal the intrafamilial classification to be in need of revision. The two tribes Iphigenieae and Uvularieae are demonstrated to be paraphyletic. The well-known genus Colchicum is shown to be nested within Androcymbium, Onixotis constitutes a grade between Neodregea and Wurmbea, and Gloriosa is intermixed with species of Littonia. Two new tribes are described, Burchardieae and Tripladenieae, and the two tribes Colchiceae and Uvularieae are emended, leaving four tribes in the family. At generic level new combinations are made in Wurmbea and Gloriosa in order to render them monophyletic. The genus Androcymbium is paraphyletic in relation to Colchicum and the latter genus is therefore expanded. -

Jervis Bay Territory Page 1 of 50 21-Jan-11 Species List for NRM Region (Blank), Jervis Bay Territory

Biodiversity Summary for NRM Regions Species List What is the summary for and where does it come from? This list has been produced by the Department of Sustainability, Environment, Water, Population and Communities (SEWPC) for the Natural Resource Management Spatial Information System. The list was produced using the AustralianAustralian Natural Natural Heritage Heritage Assessment Assessment Tool Tool (ANHAT), which analyses data from a range of plant and animal surveys and collections from across Australia to automatically generate a report for each NRM region. Data sources (Appendix 2) include national and state herbaria, museums, state governments, CSIRO, Birds Australia and a range of surveys conducted by or for DEWHA. For each family of plant and animal covered by ANHAT (Appendix 1), this document gives the number of species in the country and how many of them are found in the region. It also identifies species listed as Vulnerable, Critically Endangered, Endangered or Conservation Dependent under the EPBC Act. A biodiversity summary for this region is also available. For more information please see: www.environment.gov.au/heritage/anhat/index.html Limitations • ANHAT currently contains information on the distribution of over 30,000 Australian taxa. This includes all mammals, birds, reptiles, frogs and fish, 137 families of vascular plants (over 15,000 species) and a range of invertebrate groups. Groups notnot yet yet covered covered in inANHAT ANHAT are notnot included included in in the the list. list. • The data used come from authoritative sources, but they are not perfect. All species names have been confirmed as valid species names, but it is not possible to confirm all species locations. -

BFS048 Site Species List

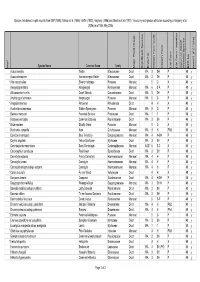

Species lists based on plot records from DEP (1996), Gibson et al. (1994), Griffin (1993), Keighery (1996) and Weston et al. (1992). Taxonomy and species attributes according to Keighery et al. (2006) as of 16th May 2005. Species Name Common Name Family Major Plant Group Significant Species Endemic Growth Form Code Growth Form Life Form Life Form - aquatics Common SSCP Wetland Species BFS No kens01 (FCT23a) Wd? Acacia sessilis Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Acacia stenoptera Narrow-winged Wattle Mimosaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Aira caryophyllea Silvery Hairgrass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Alexgeorgea nitens Alexgeorgea Restionaceae Monocot WA 6 S-R P 48 y Allocasuarina humilis Dwarf Sheoak Casuarinaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Amphipogon turbinatus Amphipogon Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y * Anagallis arvensis Pimpernel Primulaceae Dicot 4 H A 48 y Austrostipa compressa Golden Speargrass Poaceae Monocot WA 5 G P 48 y Banksia menziesii Firewood Banksia Proteaceae Dicot WA 1 T P 48 y Bossiaea eriocarpa Common Bossiaea Papilionaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y * Briza maxima Blowfly Grass Poaceae Monocot 5 G A 48 y Burchardia congesta Kara Colchicaceae Monocot WA 4 H PAB 48 y Calectasia narragara Blue Tinsel Lily Dasypogonaceae Monocot WA 4 H-SH P 48 y Calytrix angulata Yellow Starflower Myrtaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Centrolepis drummondiana Sand Centrolepis Centrolepidaceae Monocot AUST 6 S-C A 48 y Conostephium pendulum Pearlflower Epacridaceae Dicot WA 3 SH P 48 y Conostylis aculeata Prickly Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis juncea Conostylis Haemodoraceae Monocot WA 4 H P 48 y Conostylis setigera subsp. -

Eutaxia Microphylla Common Eutaxia Dillwynia Hispida Red Parrot-Pea Peas FABACEAE: FABOIDEAE Peas FABACEAE: FABOIDEAE LEGUMINOSAE LEGUMINOSAE

TABLE OF CONTENTS Foreword iv printng informaton Acknowledgements vi Introducton 2 Using the Book 3 Scope 4 Focus Area Reserve Locatons 5 Ground Dwellers 7 Creepers And Twiners 129 Small Shrubs 143 Medium Shrubs 179 Large Shrubs 218 Trees 238 Water Lovers 257 Grasses 273 Appendix A 290 Appendix B 293 Resources 300 Glossary 301 Index 303 ii iii Ground Dwellers Ground dwellers usually have a non-woody stem with most of the plant at ground level They sometmes have a die back period over summer or are annuals They are usually less than 1 metre high, provide habitat and play an important role in preventng soil erosion Goodenia blackiana, Kennedia prostrata, Glossodia major, Scaevola albida, Arthropodium strictum, Gonocarpus tetragynus Caesia calliantha 4 5 Bulbine bulbosa Bulbine-lily Tricoryne elator Yellow Rush-lily Asphodel Family ASPHODELACEAE Day Lily Family HEMEROCALLIDACEAE LILIACEAE LILIACEAE bul-BINE (bul-BEE-nee) bul-bohs-uh Meaning: Bulbine – bulb, bulbosa – bulbous triek-uhr-IEN-ee ee-LAHT-ee-or Meaning: Tricoryne – three, club shaped, elator – taller General descripton A small perennial lily with smooth bright-green leaves and General descripton Ofen inconspicuous, this erect branched plant has fne, yellow fowers wiry stems and bears small clusters of yellow star-like fowers at the tps Some Specifc features Plants regenerate annually from a tuber to form a tall longish leaves present at the base of the plant and up the stem stem from a base of feshy bright-green Specifc features Six petaled fowers are usually more than 1 cm across, -

GENOME EVOLUTION in MONOCOTS a Dissertation

GENOME EVOLUTION IN MONOCOTS A Dissertation Presented to The Faculty of the Graduate School At the University of Missouri In Partial Fulfillment Of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy By Kate L. Hertweck Dr. J. Chris Pires, Dissertation Advisor JULY 2011 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled GENOME EVOLUTION IN MONOCOTS Presented by Kate L. Hertweck A candidate for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy And hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Dr. J. Chris Pires Dr. Lori Eggert Dr. Candace Galen Dr. Rose‐Marie Muzika ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I am indebted to many people for their assistance during the course of my graduate education. I would not have derived such a keen understanding of the learning process without the tutelage of Dr. Sandi Abell. Members of the Pires lab provided prolific support in improving lab techniques, computational analysis, greenhouse maintenance, and writing support. Team Monocot, including Dr. Mike Kinney, Dr. Roxi Steele, and Erica Wheeler were particularly helpful, but other lab members working on Brassicaceae (Dr. Zhiyong Xiong, Dr. Maqsood Rehman, Pat Edger, Tatiana Arias, Dustin Mayfield) all provided vital support as well. I am also grateful for the support of a high school student, Cady Anderson, and an undergraduate, Tori Docktor, for their assistance in laboratory procedures. Many people, scientist and otherwise, helped with field collections: Dr. Travis Columbus, Hester Bell, Doug and Judy McGoon, Julie Ketner, Katy Klymus, and William Alexander. Many thanks to Barb Sonderman for taking care of my greenhouse collection of many odd plants brought back from the field. -

Flora of South Australia 5Th Edition | Edited by Jürgen Kellermann

Flora of South Australia 5th Edition | Edited by Jürgen Kellermann KEY TO FAMILIES1 J.P. Jessop2 The sequence of families used in this Flora follows closely the one adopted by the Australian Plant Census (www.anbg.gov. au/chah/apc), which in turn is based on that of the Angiosperm Phylogeny Group (APG III 2009) and Mabberley’s Plant Book (Mabberley 2008). It differs from previous editions of the Flora, which were mainly based on the classification system of Engler & Gilg (1919). A list of all families recognised in this Flora is printed in the inside cover pages with families already published highlighted in bold. The up-take of this new system by the State Herbarium of South Australia is still in progress and the S.A. Census database (www.flora.sa.gov.au/census.shtml) still uses the old classification of families. The Australian Plant Census web-site presents comparison tables of the old and new systems on family and genus level. A good overview of all families can be found in Heywood et al. (2007) and Stevens (2001–), although these authors accept a slightly different family classification. A number of names with which people using this key may be familiar but are not employed in the system used in this work have been included for convenience and are enclosed on quotation marks. 1. Plants reproducing by spores and not producing flowers (“Ferns and lycopods”) 2. Aerial shoots either dichotomously branched, with scale leaves and 3-lobed sporophores or plants with fronds consisting of a simple or divided sterile blade and a simple or branched spikelike sporophore .................................................................................. -

Supplementary Material Spatial Analysis of Limiting Resources on An

10.1071/WR14083_AC ©CSIRO 2014 Supplementary Material: Wildlife Research 41 , 510–521 Supplementary material Spatial analysis of limiting resources on an island: diet and shelter use reveal sites of conservation importance for the Rottnest Island quokka Holly L. Poole A, Laily Mukaromah A, Halina T. Kobryn A and Patricia A. Fleming A,B ASchool of Veterinary & Life Sciences, Murdoch University, WA 6150, Australia. BCorresponding author. Email: [email protected] Table S1. Raw data of plant fragment identification for 67 faecal samples from Rottnest Island quokkas Plant Family Plants No. No. No. field group faecal fragments validation sample quadrats sites present in present in Dicot Malvaceae Guichenotia ledifolia 52 9854 75 Dicot Fabaceae Acacia rostellifera 37 3018 37 Monocot Asphodelaceae Trachyandra divaricata 46 2702 145 Dicot Myrtaceae Melaleuca lanceolata 25 1506 28 Dicot Chenopodiaceae Tecticornia 13 1350 4 halocnemoides Monocot Poaceae Stipeae (Tribe) 34 1302 171 Monocot Asphodelaceae Asphodelus fistulosus 26 1103 22 Dicot Chenopodiaceae Rhagodia baccata 13 1002 46 Dicot Chenopodiaceae Suaeda australis 12 862 2 Dicot Chenopodiaceae Threlkeldia diffusa 15 829 0 Monocot Poaceae Rostraria cristata 27 788 71 Monocot Poaceae Sporobolus virginicus 5 617 2 Dicot Chenopodiaceae Sarcocornia sp . 10 560 0 Dicot Lamiaceae Westringia dampieri 5 383 46 Dicot Goodeniaceae Scaevola crassifolia 10 349 20 Monocot Cyperaceae Gahnia trifida 8 281 6 Other Cupressaceae Callitris preissii 3 148 18 Monocot Poaceae Poa poiformis 2 116 0 Dicot Chenopodiaceae Atriplex spp. (A. 1 40 1 paludosa ) Monocot Poaceae Polypogon maritimus 1 39 0 Dicot Myrtaceae Agonis flexuosa 1 15 0 Monocot Poaceae Brachypodium distachyon 0 0 1 Monocot Asphodelaceae Bulbine semibarbata 0 0 1 Dicot Pittosporaceae Pittosporum 0 0 1 phylliraeoides Monocot Poaceae Spinifex longifolius 0 0 1 Dicot Fabaceae Acacia saligna 0 0 2 Dicot Chenopodiaceae Atriplex cinerea 0 0 2 1 Dicot Asteraceae Centaurea sp .