Indigenous Astronomy; and Conferences / Seminars

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15Th October at 19:00 Hours Or 7Pm AEST

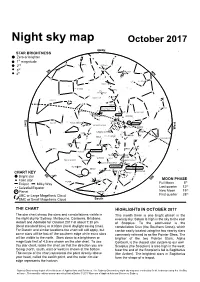

TheSky (c) Astronomy Software 1984-1998 TheSky (c) Astronomy Software 1984-1998 URSA MINOR CEPHEUS CASSIOPEIA DRACO Night sky map OctoberDRACO 2017 URSA MAJOR North North STAR BRIGHTNESS Zero or brighter 1st magnitude nd LACERTA Deneb 2 NE rd NE Vega CYGNUS CANES VENATICI LYRAANDROMEDA 3 Vega NW th NW 4 LYRA LEO MINOR CORONA BOREALIS HERCULES BOOTES CORONA BOREALIS HERCULES VULPECULA COMA BERENICES Arcturus PEGASUS SAGITTA DELPHINUS SAGITTA SERPENS LEO Altair EQUULEUS PISCES Regulus AQUILAVIRGO Altair OPHIUCHUS First Quarter Moon SERPENS on the 28th Spica AQUARIUS LIBRA Zubenelgenubi SCUTUM OPHIUCHUS CORVUS Teapot SEXTANS SERPENS CAPRICORNUS SERPENSCRATER AQUILA SCUTUM East East Antares SAGITTARIUS CETUS PISCIS AUSTRINUS P SATURN Centre of the Galaxy MICROSCOPIUM Centre of the Galaxy HYDRA West SCORPIUS West LUPUS SAGITTARIUS SCULPTOR CORONA AUSTRALIS Antares GRUS CENTAURUS LIBRA SCORPIUS NORMAINDUS TELESCOPIUM CORONA AUSTRALIS ANTLIA Zubenelgenubi ARA CIRCINUS Hadar Alpha Centauri PHOENIX Mimosa CRUX ARA CAPRICORNUS TRIANGULUM AUSTRALEPAVO PYXIS TELESCOPIUM NORMAVELALUPUS FORNAX TUCANA MUSCA 47 Tucanae MICROSCOPIUM Achernar APUS ERIDANUS PAVO SMC TRIANGULUM AUSTRALE CIRCINUS OCTANSCHAMAELEON APUS CARINA HOROLOGIUMINDUS HYDRUS Alpha Centauri OCTANS SouthSouth CelestialCelestial PolePole VOLANS Hadar PUPPIS RETICULUM POINTERS SOUTHERN CROSS PISCIS AUSTRINUS MENSA CHAMAELEONMENSA MUSCA CENTAURUS Adhara CANIS MAJOR CHART KEY LMC Mimosa SE GRUS DORADO SMC CAELUM LMCCRUX Canopus Bright star HYDRUS TUCANA SWSW MOON PHASE Faint star VOLANS DORADO -

AGM Minutes 2019 1 Minutes of The

Minutes of the 54th Annual General Meeting held at 1.30 pm (AEST)/1.00 pm (ACST)/11.30 pm (AWST) Wednesday 8 July 2020 Zoom online meeting The Meeting was opened at 1:30 am with the President in the Chair and approximately 110 members of all grades present in an entirely online meeting using Zoom. 1. Apologies Caroline Foster, Lisa Kewley 2. Minutes of the 53rd Annual General Meeting Motion that the minutes of the 54th Annual General Meeting be accepted. Couch/Lattanzio Carried 3. Business arising from the Minutes None. 4. President's Report The President, Cathryn Trott, presented a Powerpoint version of the official written report (below). 1. Council 2019-2020 Cathryn Trott President John Lattanzio Vice President Stuart Wyithe Immediate Past President John O’Byrne Secretary Marc Duldig Secretary Yeshe Fenner Treasurer Elisabete da Cunha Councillor Krzysztof Bolejko Councillor Ilya Mandel Councillor Barbara Catinella Councillor Daniel Zucker Councillor Christopher Matthew Student Representative Stas Shabala Chair, PASA Editorial Board (from January 2020) Tanya Hill (Co-opted) Prizes and Awards co-ordinator Michael Brown (Co-opted) Media and Outreach co-ordinator I would like to thank all council members for their contributions in the past year. Particular thanks go to council members holding ongoing roles in the society (John O’Byrne, Marc Duldig, Tanya Hill, and Michael Brown). Thanks go also to Gary Da Costa for continuing in his role as our “Public Officer”, and to Chapter Chairs Daniel Price, Mike Fitzgerald, Manodeep Sinha, Katie Jamieson and Dan Zucker. I would also like to acknowledge the work of Krzysztof Bolejko as Acting Prizes and Awards co-ordinator, while Tanya Hill is on leave. -

A Nn Ual R Eport 20 17– 18

Powerhouse Museum Sydney Observatory Museums Discovery Centre Annual ReportAnnual 2017–18 The Hon Don Harwin MLC Leader of the Government in the Legislative Council Minister for Resources Minister for Energy and Utilities Minister for the Arts Vice President of the Executive Council Parliament House Sydney NSW 2000 Dear Minister On behalf of the Board of Trustees and in accordance with the Annual Reports (Statutory Bodies) Act 1984 and the Public Finance and Audit Act 1983, we submit for presentation to Parliament the Annual Report of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences for the year ending 30 June 2018. Yours sincerely Professor Barney Glover FTSE FRSN Andrew Elliott President Acting Director ISSN: 2209-8836 © Trustees of the Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences 2018 The Museum of Applied Arts and Sciences is an Executive Agency of, and principally funded by the NSW State Government. MAAS Annual Report 1 2017–18 Contents Acknowledgment of country .........................................................................2 Mission, Vision, Values ..................................................................................3 Strategic direction ........................................................................................ 4 President’s foreword ..................................................................................... 6 Director’s foreword ....................................................................................... 8 Future of MAAS ...........................................................................................10 -

15Th October at 19:00 Hours Or 7Pm AEST

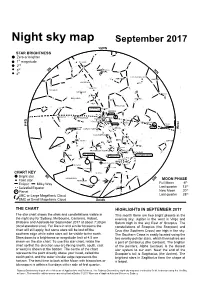

TheSky (c) Astronomy Software 1984-1998 TheSky (c) Astronomy Software 1984-1998 CASSIOPEIA URSA MINOR CEPHEUS URSA MINOR DRACO Night sky map DRACOSeptember 2017 North URSA MAJOR North STAR BRIGHTNESS Zero or brighter st LACERTA 1 magnitude Deneb nd NE CYGNUS 2 NE rd Vega CANES VENATICI LYRA Vega 3 NW LYRA NW th 4 BOOTES LEO MINOR CORONA BOREALIS CORONA CORONA BOREALIS HERCULES BOOTES HERCULES BOREALIS BOOTES VULPECULA COMA BERENICES SAGITTA Arcturus Arcturus PEGASUS DELPHINUS Arcturus SAGITTA SERPENSAltair LEO EQUULEUS SERPENS Regulus Regulus AQUILA VIRGO Altair OPHIUCHUS OPHIUCHUS First quarter SCUTUM Spica Moon onZubenel 28th genubi SERPENS LIBRA Zubenelgenubi Saturn CORVUS SEXTANS SERPENS CRATER AQUILA AQUARIUS SCUTUM CAPRICORNUS P East East SAGITTARIUS Antares LIBRA AntaresCentre of the Galaxy Antares Zubenelgenubi Teapot VIRGO Centre of the Galaxy P MICROSCOPIUM Jupiter SCORPIUS West SCORPIUS HYDRA Spica West PISCIS AUSTRINUS CORONA AUSTRALISLUPUS SAGITTARIUS CENTAURUS NORMA CENTAURUSOmega Centauri TELESCOPIUM TEA POT AlphaNORMA Centauri LUPUS CORONA AUSTRALIS ARA ANTLIA POINTERS CIRCINUS Hadar CRUX NORMASOUTHERN CROSS GRUS INDUSARA CORVUS Alpha Centauri CETUS Mimosa CRUX CAPRICORNUS TRIANGULUMTRIANGULUM PAVOAUSTRALE PYXIS SCULPTOR TELESCOPIUM AUSTRALE CIRCINUS VELA MUSCA TRIANGULUMProxima Centauri AUSTRALE Alpha Centauri MICROSCOPIUM APUS Hadar CENTAURUS 47 Tucanae APUS PHOENIX PAVO APUS SOUTHERN CROSS POINTERS TUCANA CHAMAELEON OCTANS MimosaCARINA INDUS SMC MUSCA OCTANSOCTANS SouthSouth Celestial Celestial Pole Pole CRUX Achernar -

Planets in Aboriginal Australia

The Planets in Aboriginal Australia Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Planetary Science The Planets in Aboriginal Australia Duane W. Hamacher and Kirsten Banks Subject: History of Ideas about Planets and Planetary Systems Online Publication Date: Feb 2019 DOI: 10.1093/acrefore/9780190647926.013.53 Summary and Keywords Studies in Australian Indigenous astronomical knowledge reveal few accounts of the visible planets in the sky. However, what information we do have tells us that Aboriginal people are close observers of planets and their motions and properties. Indigenous Australians discerned between planets and stars by their placement in the sky and their general lack of scintillation. Traditions generally describe the ecliptic and zodiac as a pathway of sky ancestors represented by the sun, moon, and planets. This included observing the occasional backwards motion of sky ancestors as they communicate with each other during their journey across the sky, representing an explanation of retrograde motion. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people note the relative brightness of the planets over time and information about the roles they play in their traditions around Australia. Knowledge systems outline the importance placed on Venus as the morning and evening star, making connections to the object as it transitions form one to the other through observations and calculation of the planet’s synodic period. Traditions note the relative positions of the planets to the moon, sun, and background stars, as well as inter planetary dust through zodiacal light, which is perceived as a celestial rope connecting Venus to the sun. The relative dearth of descriptions of planets in Aboriginal traditions may be due to the gross incompleteness of recorded astronomical traditions and of ethnographic bias and misidentification in the anthropological record. -

ASRC-Draft-Program-3

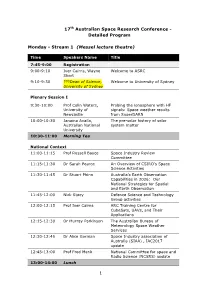

17th Australian Space Research Conference - Detailed Program Monday - Stream 1 (Messel lecture theatre) Time Speakers Name Title 7:45-9:00 Registration 9:00-9:10 Iver Cairns, Wayne Welcome to ASRC Short 9:10-9:30 ???Dean of Science, Welcome to University of Sydney University of Sydney Plenary Session I 9:30-10:00 Prof Colin Waters, Probing the ionosphere with HF University of signals: Space weather results Newcastle from SuperDARN 10:00-10:30 Janaina Availa, The pre-solar history of solar Australian National system matter University 10:30-11:00 Morning Tea National Context 11:00-11:15 Prof Russell Boyce Space Industry Review Committee 11:15-11:30 Dr Sarah Pearce An Overview of CSIRO’s Space Science Activities 11:30-11:45 Dr Stuart Phinn Australia’s Earth Observation Capabilities in 2026: Our National Strategies for Spatial and Earth Observation 11:45-12:00 Nick Stacy Defence Science and Technology Group activities 12:00-12:15 Prof Iver Cairns ARC Training Centre for CubeSats, UAVs, and Their Applications 12:15-12:30 Dr Murray Parkinson The Australian Bureau of Meteorology Space Weather Services 12:30-12:45 Dr Alice Gorman Space Industry association of Australia (SIAA) , IAC2017 update 12:45-13:00 Prof Fred Menk National Committee for space and Radio Science (NCSRS) update 13:00-14:00 Lunch 1 Time Speakers Name Title Space & Atmospheric Physics I 14:00-14:15 Julie Currie, RMIT On the use of the spectral width University boundary for monitoring magnetospheric boundary regions 14:15-14:30 Dr Trevor Harris, An overview of HFR Branch DST Group -

Koorie Education Calendar 2021

Koorie Education Calendar 2021 . JANUARY The Victorian Aboriginal Protocols for Koorie Education in We highly recommend The Victorian Aboriginal Education Association Inc. (VAEAI) was first Education Association Inc. Victorian Primary and Secondary consulting with Aboriginal established in 1976 as the Victorian Aboriginal Education Consultative (VAEAI) is the peak Koorie Schools has been produced by VAEAI people and Aboriginal Group (VAECG). The shared aim of the VAECG was to increase the community-controlled body for following requests for guidance on sources for information. presence and voice of Koorie people in education decision making at a Aboriginal Education and training appropriate protocols for schools to Where available, your local time when limited Aboriginal organisations existed. in Victoria. follow in providing a welcoming LAECG is a good first point of school environment for Koorie contact and VAEAI can assist Today VAEAI continues to represent the Victorian Koorie Community in Explore the VAEAI website , community members, and working with contacts. Try to work relation to education policy development and strategic programming at subscribe for newsletters and respectfully with the Koorie with local community local, state and national levels. follow us on Facebook. community to enrich school people and Elders, and curricula. always respect their VAEAI supports the provision of education and training that reinforces the VAEAI website: intellectual and cultural Koorie community’s cultural identity, and increases awareness -

This Thesis Has Been Submitted in Fulfilment of the Requirements for a Postgraduate Degree (E.G

This thesis has been submitted in fulfilment of the requirements for a postgraduate degree (e.g. PhD, MPhil, DClinPsychol) at the University of Edinburgh. Please note the following terms and conditions of use: This work is protected by copyright and other intellectual property rights, which are retained by the thesis author, unless otherwise stated. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the author. The content must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the author. When referring to this work, full bibliographic details including the author, title, awarding institution and date of the thesis must be given. THE JOHN MURRAY ARCHIVE, 1820s-1840s: (RE)ESTABLISHING THE HOUSE IDENTITY By KIRSTEN BANKS A thesis submitted to The University of Edinburgh for the degree of DOCTOR OF PHILOSOPHY 2013 Declaration I declare that this thesis is my own work and has not been submitted for any other degree of professional qualification. Kirsten Banks 23rd December 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I could not have undertaken this research without the financial assistance of the AHRC, who provided me with a stipend between 2009-2012. I also received annual contributions from the National Library of Scotland during this time to help with research expenses, for which I am very grateful. Whilst on a research trip in London, I had the pleasure of meeting John and Virginia Murray at 50 Albemarle Street, whose time and interest in my thesis was much appreciated. -

Building Bridges 2017 Brochure

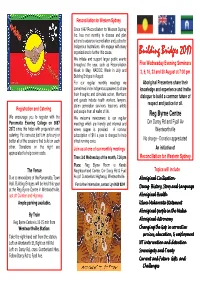

Reconciliation for Western Sydney Since 1997 Reconciliation for Western Sydney Inc. has met monthly to discuss and plan actions to advance reconciliation and justice for Indigenous Australians. We engage with many organisations to further this cause. Building Bridges 2017 We initiate and support larger public events throughout the year, such as Reconciliation Five Wednesday Evening Seminars Week in May, NAIDOC Week in July and 2, 9, 16, 23 and 30 August at 7:30 pm Building Bridges in August. For our regular monthly meetings we Aboriginal Presenters share their sometimes invite Indigenous speakers to share knowledge and experience and invite their thoughts and stimulate action. Members dialogue to build a common future of and guests include health workers, lawyers, stolen generation survivors, teachers, artists respect and justice for all. Registration and Catering and people from all walks of life. Reg Byrne Centre We encourage you to register with the We welcome newcomers to our regular Parramatta Evening College on 9687 meetings which are friendly and informal and Cnr Darcy Rd and Fyall Av 2072 since this helps with preparation and where supper is provided. A nominal Wentworthville catering. You can also just turn up to any or subscription of $10 a year is charged to help better all of the sessions that build on each offset running costs. No charge - Donation appreciated other. Donations on the night are Join us at one of our monthly meetings An initiative of appreciated to help cover costs. Time: 3rd Wednesday of the month, 7.30 pm Reconciliation for Western Sydney Place: Reg Byrne Room at Karabi The Venue Neighbourhood Centre, Cnr Darcy Rd & Fyall Topics will include Due to renovations of the Parramatta Town Av (off Cumberland Highway), Wentworthville. -

Asterisk: GILL GATFIELD

Asterisk: GILL GATFIELD ARTIST CONCEPT IMAGE Australian stone—Pilbara marble, Chillagoe marble, Sydney ‘Tunnel stone’, heritage sandstone Approx. 12m Dia. x 1m H Location of public artworks ASTERISK: GILL GATFIELD Concept ASTERISK: GILL GATFIELD Named after the Ancient Greek word ‘asteriskos’ meaning 'little star', the distinctive star shaped sculpture Asterisk makes connections across cultures, time and place. Combining ancient stones and celestial form, the sculpture explores the metaphysical realms of earth and sky. It speaks to human journeys and ancient stellar navigation systems used to guide Indigenous travellers on journeys far and wide. Made from four unique rock types sourced from across Australia, the sculpture's intersecting planes reveal markings that trace the history of the oldest continent in the world. One plane is a composite of stone discovered during construction of the WestConnex M8, deep within the earth below the sculpture’s site. This stone, anchored by rock from the north and the west, holds the memory of this land, reshaped to enable new destinations. Asterisk is orientated to Ginan, the smallest star in the Southern Cross, recently officially given its Australian Aboriginal star-name. Situated on Cadigal and Kameygal land, welcoming visitors at the entrance to new sculpture parklands, Asterisk is a modern compass placing equal value on different perspectives. ARTIST CONCEPT IMAGE From https://www.gillgatfield.com/asterisk/ Concept ASTERISK: GILL GATFIELD The circular form of Asterisk invites people in and generates intrigue–from every angle the artwork reveals a new and unique view. Older children and adults can see the star shaped connection at the centre, touch the smooth stone, explore the intersecting planes and discover complex shadows cast within and beyond the form. -

The Planets in Indigenous Australian Traditions

Preprint - Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Planetary Science The Planets in Indigenous Australian Traditions Duane W. Hamacher1,2 and Kirsten Banks3 1Monash Indigenous Studies Centre, Monash University, Clayton, VIC, Australia 2Centre for Astrophysics, University of Southern Queensland, Toowoomba, QLD, Australia 3School of Physics, University of New South Wales, Sydney, NSW, Australia Emails: [email protected] | [email protected] Abstract Studies in Australian Indigenous astronomical knowledge reveal few accounts of the visible planets in the sky. However, what information we do have tells us that Aboriginal people were close observers of planets and their motions, noting the relative brightness of the planets, their motions along the ecliptic, retrograde motion, the relationship between Venus and its proximity to the Sun, Venus’ connection to the Sun through zodiacal light, and the synodic cycle of Venus, particularly as it transitions from the Evening Star to the Morning Star. The dearth of descriptions of planets in Aboriginal traditions may be due to the gross incompleteness of recorded astronomical traditions, and of ethnographic bias and misidentification in the anthropological record. Ethnographic fieldwork with Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander communities is revealing new, previously unrecorded knowledge about the planets and their related phenomena. Keywords: Indigenous Knowledge, Cultural Astronomy, Aboriginal Australians, Torres Strait Islanders, Ethnoastronomy, Archaeoastronomy, History of Astronomy 1 Introduction The study of Indigenous astronomy has revealed a wealth of information about the role of the Sun, Moon, stars, and planets in the traditional Knowledge Systems of Aboriginal Australians (Norris 2016). Indigenous cultures around the world, particularly the many hundreds that exist in Australia, maintain complex astronomical knowledge systems that link the positions and motions of celestial objects and to navigation, calendars, subsistence, and social applications (Hamacher 2012; Johnson 1998; Cairns and Harney 2003). -

The Great Celestial Emu Is My Favourite Aboriginal Constellation Says Kirsten Banks

Media release - no embargo - 11 August 2018 The Great Celestial Emu is my favourite Aboriginal constellation says Kirsten Banks Kirsten Banks’ heritage can be traced back on her father’s side to ancestors of the Wiradjuri people in central New South Wales. Wiradjuri is one of the largest language groups in Australia. In her younger years, Banks had learnt a few Dreaming stories. The one that sparked her imagination and inspired her to explore the night sky in more detail was the story connected with the Emu in the Sky. She became intrigued with how much we don’t know and with wanting to share the astronomical knowledge of her ancestors. Her research has revealed a wealth of traditional star knowledge stretching back into deep time. “For tens of thousands of years, Aboriginal people have been using the stars for so many cool things,” she says. “It blows my mind. I love sharing that knowledge with other people.” “Knowledge systems that link the positions and motions of celestial objects to navigation, calendars, subsistence, and social applications,” Banks says. “Indigenous people are careful observers of subtle changes in the positions and properties of celestial objects and noted both obvious and rare celestial phenomena, such as meteors, comets, eclipses and fireballs,” she says in her report on The Planets in Indigenous Australian Traditions, written with fellow astronomer Duane Hamacher. It is no surprise to Banks that: “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander people paid careful attention to the motions of solar system bodies through careful observation, which was recorded and passed to successive generations through oral tradition and material culture.” “Aboriginal and Islander people distinguished planets from the background stars, noted their changing positions in the sky, and their changing positions relative to each other,” she says.